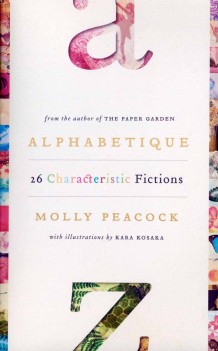

An Interview with Molly Peacock

Molly Peacock is author of six books of poetry, including Cornucopia: New & Selected Poems (2002) and The Second Blush (2009) as well as the best-selling biography The Paper Garden: An Artist Begins Her Life’s Work at 72 (2010). Alphabetique, comprising 26 fanciful tales based on the letters of the alphabet, is her first work of fiction.

Laura Bast: How did Alphabetique come about?

Molly Peacock: A dear friend of mine, Phillis Levin, had given an assignment to her students to write a poem with an ambiguous pronoun, where you may not know who or what is behind this pronoun, and your reader certainly doesn’t. So I thought, I’m going to try this. When I started it, I was thinking about the idea that things only mean if they come into language. As a child I thought, “I have thoughts in my head. But I can’t put them into words.” I think that is the essence of poetry. A poem is about the things you don’t have words for. My thought was about this dilemma that I had as a young child, about trying to say things. So I put that dilemma into a kind of character, and I just used the pronoun “he.” But it got so complicated! I thought, I’ve got to give up this pronoun idea, so I called the character “C.” That was the seed of one story, and, it turned out to be the seed of the book.

LB: What about the alphabet form? Where did that come from?

MP: I have an interest in Anglo-Saxon poetry, and I have translated a few things. Anglo-Saxon is not an inflected language like a Romance language. The poetry can’t rhyme. It doesn’t depend on end sounds; it depends on beginning sounds, and the lines heavily alliterate. So, that’s the kernel of the formal aspect of how these poems—eventually stories—began. I didn’t think, “Oh, now I’m going to do the whole alphabet.” I went on with the rest of my life. But I went back to the C piece, horsing around with it. I was never deeply happy with it, but then Phillis and I went to a funeral together of someone we knew a long time ago who had committed suicide. At this dreadful funeral, I began thinking about the letter B. It just sort of spun out of me as I recalled youthful times of being a writer. I think I did five letters before I thought, “Duh! You could do all twenty-six.” It’s a bit of a banal thought because I think every writer has abecedarian impulses.

LB: You think every writer does?

MP: Well, many writers do. Think of how many alphabet books there are. It’s been a tradition since there was printing.

LB: Why do you think that it’s such an interest for writers? Because they’re just getting back to the basics?

MP: Because the alphabet originally came through our hands. Aleph means ox. Beth means house. These are the pictorial ideas at the founding of the alphabet. But I didn’t want to make Alphabetique learned; there are many academic books about such things. I was playing.

I was writing a big biography at the time, with heavy research, facts. I was working away trying to put these facts into sentences that might possibly interest somebody. Even though biography requires imaginative acts, I didn’t really have anywhere for my imagination to play. So that’s why I kept these alphabetical pieces going.

LB: When did they go from being poems to being stories?

MP: I like my poems short and lyrical. There can be a narrative backdrop, but essentially I’m driving the poem to a lyric moment. It’s kind of a still place. And because I’m doing that, there’s an everyday waking logic that doesn’t have to apply. Your reader, who knows it’s a poem, leaps with you; it’s part of the agreement.

But the question came up of what category the book would be sold in. Frankly, they were going to sink more money into this illustrated book than into a collection of traditional poems. So I said, Why don’t I see what I can do about creating these things as prose? I mean, What would happen if I teased out the more story-like elements of them? What if I didn’t drive each piece to its still point? A story can’t leap in the same way a poem can. Not to say that a sophisticated story doesn’t have leaps, but there’s certainly a sort of logic that prose has that poetry in lines forgoes because the poetry is carried by its music, and you can accept all kinds of emotional content because music is emotion. But prose has simpler musical elements: phrases built into clauses built into sentences.

I realised that the leaps I was making in the poems weren’t serving the stories. First I took them out of lines and formed them into paragraphs. And then I began to see, oh well, if they’re in paragraphs, something I said later on has to go in front. And something I said up front has to be delayed. In traditional storytelling, sequence is everything. Then I realised I wanted to keep the alliteration, but not have it be so unbelievably dominant that it was going to impede the flow.

LB: The alliteration used to be more dominant than it is now?

MP: Yeah. There’s a lot of it! I spent much time with an actual print dictionary looking up words. There’s more alliteration in the beginnings of the tales—because I set the tone with the sound of each letter—they needed to be fun! I wanted them to be lighthearted. I wanted them to be brightly coloured. Besides alliteration in each tale, I also wanted some piece of wisdom that I could unearth from the experience of each letter (which often shares some kind of experience with something in my life, although not always absolutely directly). For instance, I’m not a mother, and A is trying to name her first child. That nugget of wisdom in the story took the place of the still point in the poem.

LB: What struck you most about the final result?

MP: What I realised when I finished this book is that each character is saved by imagination. If you can imagine something new, you can imagine your way out of dire circumstances. And if you shut down too much, you shut down your imagination. Fear, for instance, shuts down imagination. When we see terror operating in the world, part of what happens, and part of why the terror grows is that people can no longer have an imaginative response to it. And I certainly know for myself that imagining my way out of things has been very rescuing.

LB: What did you think of the reviews of Alphabetique?

MP: I absolutely loved them. They were all full of responsive wordplay, from Steven Beattie in the National Post to Rebecca Silver Slayter in Maclean’s to Warren Clements in the Literary Review of Canada. As a poet I am often called a formalist. I love verbal experiments and verbal structures of all kinds. So the minute the Oulipo poets were suggested by reviewers, I said, of course! I saw the connection. I have an affair with the French language. I have thirty French vocabulary cards sitting right next to my bathroom sink right now, and periodically I enroll in a class to improve myself. So, all of this stuff was in the air around me, in that less-than-conscious way that writers operate.

LB: Is this book available in the States?

MP: No! I hope it will be, though.

LB: How do you think it would be received in the United States?

MP: I honestly don’t know. It’s not quite categorizable. And because it isn’t categorizable, if I was spectacularly famous and did it—

LB: It would be fine.

MP: Maybe it would be fine. It’s a comment on the depth of difference between the two literary cultures. But, why would you call this book “Canadian”? Other than the fact that it was written in Canada. I think you could call it Canadian because of the contract with the reader. There’s a certain faith on the part of Canadians that the writer is going to lead the reader somewhere. This is opposed to the quick culture in the United States. In the quick culture, if you don’t see what the author intends immediately, you don’t have time to stop and find out. A reader’s reaction can almost be anger at that.

LB: Where do you think that difference comes from?

MP: How about an ice cream analogy? In New York, the number of brands and flavours of ice cream in a supermarket will be extravagant. Here, the economy doesn’t support the terrifying multiplicity of that variety. A person doesn’t have so much pressure on the choice button. So what has really interested me is that the reviewers of Alphabetique got it right away. Because there isn’t the same kind of pressure, because they had time to process this unusual, beautifully illustrated abecedarian book for adults. (Every time I see it, I mentally thank Kara Kosaka for the stunning collage illustrations.)

LB: Canadian readers are a lot more patient. But do you think that sometimes allows Canadian writers to be a little bit sloppy or lazy?

MP: I agree. There’s a high tolerance for sloppiness. There’s sort of a pacing problem too. Too laid back; too slow. Readers are smart. They can get something a lot faster. And besides, they can look things up. It’s a snap. So yes, but I think on the other hand, that there’s something to be said for a kind of slow, wakening curiosity that still exists here in the reading culture.

LB: Steven Beattie notes that these stories tilt more toward “fable or allegory,” which “immediately sets the book apart from the vast majority of Canadian short fiction.” Do you agree that your book is decidedly different from most of what’s being writing in Canada in the short fiction genre?

MP: Yes! And I think we’re missing out on the fable. Literature that comes out of essential needs for identity is necessarily realist. But there’s a different tradition of literature that comes out of the play of imagination. Because fantasy traditions come out of folklore, folk tale, fairy tale, mythology, and what we think of as “old culture.” I’m wondering: is Canadian culture old enough to make a literature of fantasy?

LB: Evidence suggests no! Because there isn’t very much of it. Right?

MP: There isn’t. But people could start.

LB: We could. But in Canada, we always suffer from that inferiority thing.

MP: Is it the inferiority thing that makes Canadians some of the funniest people on earth? On the other hand our literature can be quite humourless. You know, somebody drags themselves from the farmhouse to the barn in a snowstorm. I love when Canadian writers are very droll, very funny. I don’t think of myself as a humorous writer, but I think of myself as someone with whimsy. But I never thought I would do this book. Alphabetique came as a complete surprise. I was kidnapped by it.

Laura Bast edits law textbooks by day and writes poetry reviews by night.