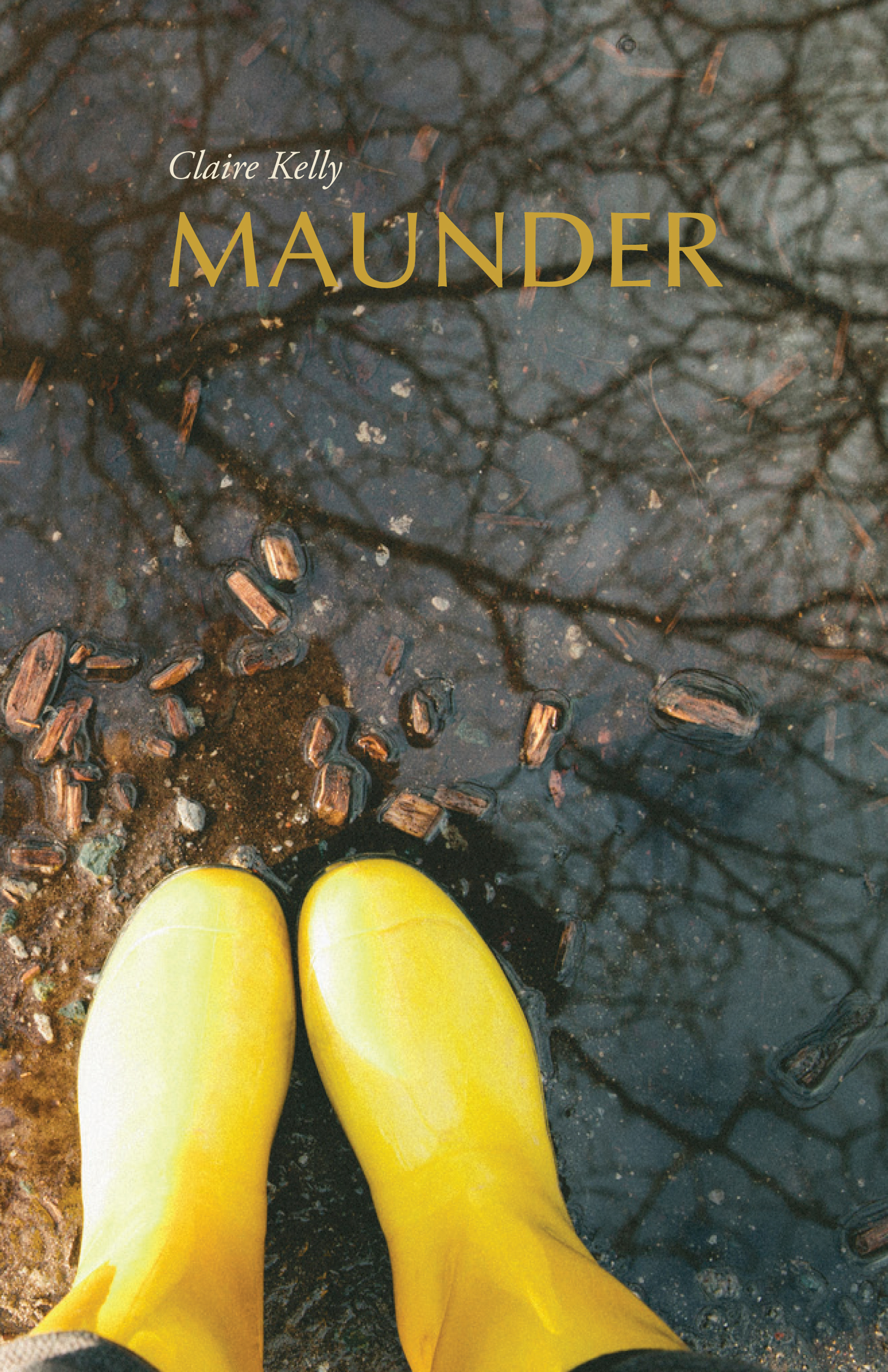

Meandering Through Maunder: A Review of Claire Kelly's Debut

True to its title, Maunder (Palimpsest Press), Claire Kelly’s revelatory first collection of poems, travels literally and figuratively, using different modes of transportation—walking, buses, cars, horses, sulkies, canoes, trucks—to explore how one exists in relation to their surroundings: to Canadian cities, to strangers on the bus, to nature. The first of Maunder’s two sections is comprised of three poems, the last of which, “Keeping Track, Keeping Pace,” even personifies different modes of walking—the swagger, the lurch and reel, the hobble and the strut. Each has its own rhythmic syntax, demonstrating an impressive range of voices. (“Maundering” goes unmentioned, as its exploration takes up the whole collection.)

Another early poem, “The Observer Effect,” introduces readers to one of the collection’s key themes, observation and interruption. An epigraph from Psychology: A Journal explains that this effect “refers to changes in a subject's behavior caused by an awareness of being observed.” The poem then describes an idle afternoon:

How among poppies we reclined,

fingers carelessly strumming

the spindly stems of less

vibrant wildflowers

But throughout there is the sinister sense of an impending threat:

How after disturbing and being

disturbed by fire ants

we moved on.

Animals impeding—sometimes literally being eaten by a bear or whale, sometimes vultures, crows, eagles, and other winged creatures circling overhead—recur again and again in this collection.

Of course, you can't write about walking without referencing Virginia Woolf's essay “Street Haunting,” or Frank O'Hara's traversing conversational poems. Woolf's essay argues for the necessity of walks to maintain an inner connectedness: “is the true self neither this nor that, neither here nor there, but something so varied and wandering that it is only when we give the rein to its wishes and let it take its way unimpeded that we are indeed ourselves?” Maunder’s “Street Haunting” addresses both influences—the title from Woolf, the epigraph from O’Hara. Tripping through these broken line breaks, the poem inquires whether a failed walk can also be fortuitous:

Erratic steps, clipped

dodges. Collision being

the true failure to connect.

An inner walk gone wrong:

my mind, a gymnast's spiralling ribbon

Kelly has a keen eye both for what one acknowledges in their surroundings as well as what goes unacknowledged. In addition to things people don't see, or choose not to see, she also thoughtfully considers the complicated nature of walking, of being a flâneur, when one is a woman. In “Before the Dream in which She is Followed Begins,” a man like a “Tom Sawyer penknife that sticks and needs oiling” approaches a woman. His heavy shoes and shuffle appear to demand the woman’s attention:

My own love is grey-mottled, lame

my seagull love cries out and struts the parking lot

my seagull belly is never quite full

my seagull timepiece is always calling out the hour

when it is not the hour, its strap pinches!

The flâneur is, of course, a concept of male privilege, attributed to Baudelaire and nineteenth century Parisian aesthetics. Kelly’s poem reminds us that if a woman chooses to stroll about town, she must confront the threat of violence. But the poem also ends triumphantly, as the woman walks away and pays no attention to the seagull-man.

Spread throughout Maunder are the “Four Seasons on a Bus” poems, which provide a necessary structure and a palpable sense of time passing as the book progresses. Spring is a teenager, characterized by a lamb that has “turned feral, violent. Won't be sheered”; summer is a group of tanned, giggling girls “their sundress hems— / protective as bud-sheaths”; fall is a stressed-out student who “holds onto the pole, / but barely”; winter is an old man who has “gone / on a bender.”

“We met midway up the hill,” a string of thirteen conditional phrases that repeat like an enchanting refrain, is one of the most affecting poems in the book:

as though grass blades were jury members we had to sway

as though the nighthawk’s electronic chirps foretold an early frost

as though I might snatch a clump of moss, dry it for burning

…

as though the whirligig spun for you alone and stilled when I breathed in its direction

Each phrase is seemingly impossible, a fantasy, yet undercut by the simplicity and straightforwardness of the title, the meeting that ties these lines together. The fantastical is grounded in the real, and the reader is moved by the potential for that moment of connectedness to occur.

The book closes with “Maunderings,” a long poem with five couplets on each page, fragmented aphorisms and similes collected from internal and external witnessings:

The birch trees' fawn-hued under-bark is a warning.

Not just white strips peeled for lazy blaze. But signposts. Famine bread.

Each couplet is a striking, compressed, metonymic thought, a distillation of noticing and being present. The final couplet of the book, a walk in winter, is also a meditation on writing itself:

The padded snow underfoot, pure compression, is the sharpest thing.That you once had a shortcut. That you once had time not to waste.

These poems, whether long rambles or alleyway shortcuts, are not time wasted. A walk is not always a great revelation of the “true self”; rather, this collection proves that we need the failed walks, the incomplete, the not-quite-understood, to begin to see the bigger picture around us.