Watershed Moments

© Annie Lafleur

Thirty-seven-year-old Montreal writer Maxime Raymond Bock is the author of two short story collections, Atavismes (2011), and Les noyades secondaires (2017), as well as two novellas, Rosemont de profil (2013), and Des lames de pierre (2015). (Atavismes and Des lames de pierre were both translated into English by Pablo Strauss.) Bock was awarded the Adrienne-Choquette prize for Atavismes in 2012, and his work has been favourably reviewed in The New Yorker, Le Devoir, La Presse, The Gazette and Quill and Quire.

I spoke with Maxime Raymond Bock over email. His answers have been translated from French to English.

MELISSA BULL: I cited your first book, Atavismes, a collection of short stories, as my favourite read of 2011 in a Maisonneuve blog post (“Maisy’s Best Books 2011”). I was stoked when I heard you had a new collection—Les noyades secondaires—out.

Les noyades secondaires, published in the fall of 2017 by Le Cheval d’août éditeur, is a collection of short stories that are set in and travel through different eras and neighbourhoods of Montreal. The stories, some of which are linked, are written with particular attention to tone and pace. Some of the more sweeping stories, written with greater formality, draw the reader into more of an overarching, cinematic view of the city. Others are written with more immediacy and intimacy. What ties them all together is the city itself.

I’m a Montrealer. My parents met in Montreal, and I’ve lived here most of my life. I think for both my parents, Montreal provided a kind of escape from more conservative families in their more conservative towns. My father was from Toronto, my mother is from Quebec City. (My great-aunt in Toronto used to ask my mother, “Do they still drive on sidewalks in Montreal?” I feel like there must have been a Lili St-Cyr viewing escape from Protestantism action happening once upon a time.) My father, in particular, loved Montreal, and when I was a kid, he’d take me on tours of all the metro art—not the graffiti, but the actual art created for each individual station and tell me the stories behind it. He’d read to me from Jeanne Mance and Jacques Cartier’s letters and diaries. We’d walk over the mountain—he’d always insist all public parks, all public art belonged to us—and he’d tell me about the people who used to live there, and wondered how it might have been. We’d walk around the Old Port and talk about how the ships used to come in and who recorded their passages, then head over to the Notre-Dame-de-Bon-Secours church to see the models of ships hanging from the rafters, and imagine all the people who’d prayed for their mariners. My father said “marin” with a hard English “r” and my whole French family would laugh about it. He himself had been “un marrrin” once, long ago.

I say all this because I’m sure it’s partly why I respond to your book. My deep affection for Montreal is coloured by having lived all over the city, and it’s very much informed by my father’s stories of its history. While the stories in Les noyades secondaires are all based in Montreal, the city never feels touristy. That’s because, I think, this is an insider’s Montreal. Or rather, and better yet, this is multiple insiders’ Montreals. The characters in the book are all very much at home in their neighbourhoods, in their timelines. As a result, the book as a whole feels kind of like a literary love letter to the city.

Can you tell me a bit about why you want to write about the city in such depth? Is this where you’re from? Which parts feel like home?

MAXIME RAYMOND BOCK: I’m glad my affection for Montreal resonates with yours, and I’m very happy that you like Les noyades secondaires for its Montreal setting, in particular after you liked Atavismes, which was more focused on the history of Quebec, Canada, and even more generally, North America. Noyades could be Atavismes’ cousin. They’re linked by their form and their explorations of different literary genres, but they're also different from one another. Even if half the stories in Atavismes are set in Montreal, after the book was published, I became associated with neo-regionalism, something I don’t at all identify with. Rather than distancing myself from this association by writing essays or speaking about it publicly, I chose to let my work, little by little, establish its own cartography. I told myself: I grew up in the alleys of Rosemont, not in Mont-Laurier or in Gaspé, and I can tell the story of my city with the depth of knowledge that I have, as a local. The city made me, and I am a part of it. So let’s say that with Noyades, as a writer, j’arrive en ville properly, as well as in the figurative sense.

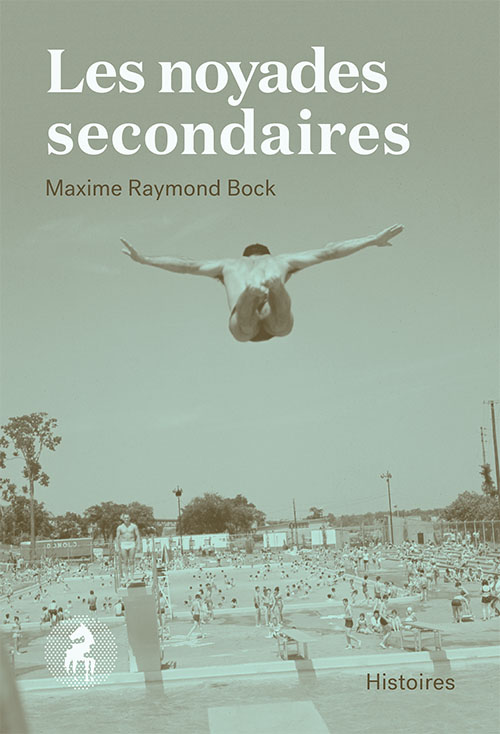

The book is without a doubt a love letter to my city, even to the selection of the cover picture—a photo taken in 1965 at the Île Sainte-Hélène pool. Among the aquatic images we had access to, the choice wasn’t hard to make because this scene happens in one of the stories, “Exérèse”—a nice coincidence. So yes, the east end of Montreal is an essential part of my identity. My childhood took place entirely in Rosemont, but I’ve also lived in Villeray, in Mercier, and I’ve lived in Ahuntsic for almost 15 years. But as a lifeguard I watched pool rats in Saint-Laurent, in Tétraultville, in Hochelaga, in the Centre-Sud, etc. and as a swimmer, I competed all over the city, in DDO, Beaconsfield, Pointe-Claire, Saint-Henri, Rivière-des-Prairies, etc. I feel at home in Ahuntsic today but never as much as I do in Rosemont. Every time I go back I have the feeling that it’s my neighbourhood, and that I’d like to live there again. And I’ll always feel at home in Hochelag’. Not so much in Ho-Ma.

MB: As I wrote in my review of Atavismes, this interest of yours of weaving the past into the present, of making it current—it feels new. Surprising. And relevant. It’s clear you’re not simply rehashing any lumberjack archetypes—your project feels far more nuanced and personal.

Why is the presence of the past interesting to you? Do you start with a story or start with the research? How do you envision this presence of the past in our everyday lives?

MRB: Yes, the persistence of the past is a bit of an obsession for me. I try to notice it as often as possible. Museums are important, of course, you have to visit them and soak up what they give us (have you seen the new wing at the Pointe-à-Callière Museum Les Premiers Montréalistes 1642-1643? deeply moving), but the past doesn’t just live in the words of specialists. It’s in the family stories we retell. It is more easily visible in architecture, but it’s in nature too, for example in the huge trees at Parc Lafontaine, of Mont-Royal or of Nicolas-Viel Parc, which began to grow long before the birth of our great-grandparents. When we feel that the past is always with us, transformed, certainly, but still very much a part of the reality we experience, both the past and the present are enhanced and charged.

And the “historical” past is much closer to us that we feel in our day, with our quickly-evolving technology giving us the impression of a present that is endlessly erased and updated. I’ll give you an example: I grew up very close to my grandparents, who were born in 1925. I hope someday I’ll have grandchildren who'll grow up with me… and they could live until 2125—my son is eight years old… And I have known and liked people who've touched worlds as distant as 200 years ago. That’s why, for example, the War of 1812 or the Patriot’s War of 1837–1838 don’t seem that long ago… The way I challenge myself with history, in my writing, is to get out of it as an abstraction, a didactic representation, and really make people live in the past. Your armpits stink, you cut your fingernail too short and it hurts the whole three days it takes to grow back, your baby is awkward when they take their first steps and you feel at that moment a joy you never knew before, the boss is an asshole: it was as real then as it is today.

In fiction, historical accuracy is essential, but it’s just part of the equation. Literature has possibilities that history, as a scientific discipline, can’t, by its very scientific nature, entertain. Literature can address the incoherences, paradoxes, and contradictions at work in our lives. And literature can especially address what is consumed without leaving a trace and therefore won’t be revealed in historic discourse: intimacy, interiority. That’s where I try to go when I travel through time. There is abundant research for each text, but the preliminary idea—maybe a single scene, or even a detail from a single scene—has to appear to guide this research. Once I’d determined, for example, that I was going to send my characters under the Turcot Exchange in “Sous les ruines,” I had to learn as much as possible about the tanneries in New-France. In the end, I learned much more than is said in the short story (which is very little, in fact), but it wasn’t important to precisely name the tools or the products or the techniques that were employed, etc. I just had to have my character show up in the most plausible environment possible.

MB: Brother Alfred Bessette (1845–1947), canonized as Saint André of Montreal, was reported to have healed thousands in his time. His heart is a relic on display at the Saint Joseph Oratory. In 1973, thieves broke into the Oratory and stole Brother André’s heart. A few days later, the thieves demanded a 50 thousand dollar ransom for the heart, which the Catholic Church refused to pay. Almost two years later, a lawyer got a call directing him to the location of the missing heart, in a storage locker. Your story, “Exérèse,” imagines how the heart robbery might have gone down.

Did you always know about Brother André’s heart missing and being returned? What made you want to tackle it in fiction?

MRB: My grandmother went up the stairs of the Saint Joseph Oratory on her knees many times over the course of her life, so it’s as if Brother André and the Saint-Joseph Oratory have been part of our family folklore forever. And Brother André is also a big part of the Catholic Québécois imaginary of the 19th and 20th centuries, so I wanted to have fun with this factoid, which is at once funny and gory. Because, unless you’re approaching it from a scientific or biological perspective, it’s difficult to find a heart preserved in formaldehyde anything other than repugnant. But Brother André’s heart couldn’t care less about science, it makes miracles. It’s the absolute symbol of love, so, the perfect fodder for fiction.

The story “Exérèse” is a the first text in a triptych of the “Noyades secondaires” that gives the title to the whole book, a triptych inspired by my family history (there is also a diptyque titled “Les arts impraticables,” and another called “La ville invisible” in the collection…), and I wanted to give a mythic scope to my origins, like a tale, very much influenced in the tone by Jacques Ferron. It was fun to manipulate the opposing forces of a crime as significant as the robbery of this inert chunk of flesh (which brings us back to our materiality) having belonged to a saint who would have healed thousands of people thanks to his gigantic love. His power, once dislodged from its pedestal at the Oratory, had to reactivate a little!

People undoubtedly experienced some great love stories in 1973–1974, in all the time that the heart was missing. And that timing is approximately when my parents were dating, before they married. It’s hard not to make use of these materials when they’re all so potent. For example, I would never have dared to name both the couple’s mothers with identical first names were my own grandmothers not effectively both named Thérèse: you can’t invent that. But since it’s taken from reality, the fiction can take off from there.

But for the heart-stealing, the criminals, their methods of breaking in, their apartments in Hochelaga, all that is fictitious, while gleaned from what you can find online, from the criminal negotiator and crime reporter Claude Poirier’s recollections, to the newspapers of the time, etc. We still don’t know exactly who stole Brother André’s heart, or how. If you research the crime online, you can find blogs where old criminals brag about having done it—to go down in posterity—refuting Claude Poirier’s work. It’s fun.

MB: Just as the larger history is part of all of us, I realized, reading your book, that mine and my family’s personal histories are also shared experiences. So many specific details in Noyades touched on aspects of my own life. I grew up across the tracks from those Turcot Yards archaeological excavations in “Sous les ruines.” My mother, like one of your characters, was expected to wear blue to her wedding, and also teaches art at the Judith Jasmin pavilion at UQAM, the program two of your characters attend. I, like your swimming characters, took lifeguard training in Montreal’s public pools. Like another of your characters, I also got a concussion from tobogganing. And like yet another, I’ve been to the ER at the Jean-Talon hospital. So part of my enjoyment was those moments of recognition, which might be exciting in part because while there are certainly a number of books about our city, it’s not a city that’s been written about to the extent that others, like New York or Paris, may have been. But your book also made me realize that of course, throughout Quebec, many women of a certain generation were forced by the Catholic Church to wear blue when they married. There must be hundreds of stories of kids getting concussions from tobogganing down icy hills in Montreal. It all belongs to all of us.

Reading your book had me thinking about how, maybe through our educations, we sometimes genericize ourselves in our writing and it’s important to remember those specifics from our lives in our work. Not in a way that I mean everything has to be taken from our own lived experiences, but that the specificity of place has value. There are stories in that specificity.

MRB: I felt the same thing several times when reading your poetry collection, Rue. Community is created easily in the shared experience of a place (in this case, our city), but there’s also a deeper community woven into the experience of life’s intimate details that can seem insignificant in their smallness but that are in fact very solidifying, especially when this experience is a generational one. In your poem, “Claremont, Apt. 45,” for example, those spoonfuls of sugar that do not dissolve in the bowl of Cheerios—the milk is saturated with it. I ate an incalculable amount of them, too.

It’s in these details that our identificatory potential in literature is at its best. When the collective finds themselves not in the great moments of history but in the similarly intimate trials: it’s a sharing of solitudes. When that happens, you can feel that literature speaks of life tangibly; it’s not a bookish adventure, just an act of thought and imagination, one of its roles is to make us lift our eyes from written and printed characters and remake the world in all its dimensions—emotional, relational, moral, political, etc. I mentioned it earlier in my approach to historical fiction: for me, there’s no macro without the micro. But it’s clear that in my more recent texts I lean more towards the intimate, Noyades is about the writing of the body, wounds, diseases, and fragile organs.

You say we have a tendency to make our characters generic in our texts (you specify “to make ourselves generic” but I’m broadening the notion to include our characters). It’s true, and it’s a challenge not to reduce our characters to actantial, or dualistic characteristics that serve only to forward the plotlines rather than depict the substantive richness of each human being, with contradictions, flaws, areas of shadow and light, etc., But both strata co-exist. Even if we are distinct individuals, we are at the same time archetypes in a number of ways...

I’ll go back to my family, for example. Its personal history is shared by a large number of other families, that of generations were confronted with in the 1970s. When I look at my family, I see of course what they are—or were—in their individuality. But I can’t help but also see archetypal characters: my French-Canadian grandparents, practicing Catholics, my atheist Québécois parents, the class struggle at play in their marriage, etc. Society in general is reflected in family relationships. So no, I don’t see anything wrong with using my personal experience to feed my writing, on the contrary, it’s what allows the work to hit the right note. Whatever happened for real doesn’t matter. In any event, those who write autofiction claim to be sticking to reality but they invent and lie all the time, and those who write “pure” fiction mine endlessly from their own lives. It’s all in the way you treat the experience: voice, form, work, work, work.

MB: The title of the book, Les Noyades secondaires, refers to what’s anecdotally known as a “secondary drowning,” or a “dry drowning.” The idea is that someone would take water into their lungs, nearly drowning, but not. They would survive, however, the water remain in their lungs, and they would die of drowning at a later date. According to science, dry or secondary drownings are not medically accepted conditions. But this is a collection that not only features swimmers, but where the second act of many of these stories has a sudden shift in direction. There’s also the constant theme of individuals being pulled by life’s tides in directions they might not expect. Of being submerged by life’s tolls.

MRB: Yes, a secondary drowning is a pulmonary edema that can be potentially fatal. You were right about the changes of directions and the reversal of unexpected situations, the insurmountable pitfalls. There is, of course, the field of aquatic sports, and a good number of suffocations weave through the book. Metaphorically, secondary drownings. That expresses all sorts of ways in the stories of Noyades, in the dysphoric resurgence of the past in the historical short stories, for example, or in the reunion of old friends that fall a little flat. You know you are the only person who’s asked me this question until now? I'm happy that you’re bringing it up. It’s probably because you were a swimmer.

LIGHTNING ROUND

Favourite Montreal diner: La Banquise after the bars close.

Favourite Montreal bar when you were under- or barely-of-age: Les Foufounes électriques. We went every week. I was the only one not to get carded—because of my sideburns.

Favourite Montreal park: Parc Jeanne-Mance by way of Rachel, walking towards Parc Avenue and at the foot of Mont Royal. My adolescence: “Meet you at the lions.”

Favourite literary Montreal: I’m wary of the literary scene. But anything Catherine Cormier-Larose does is dear to my heart.

Favourite Montreal movie: 20h17 rue Darling. Coincidences, violence, alcoholism, despair, Hochelaga, my kind of misery. By Bernard Émond, with Luc Picard.

Favourite Montreal street: Masson. My favourite village Main Street.

Favourite Montreal alleyway: Dandurant–Holt and 5e–4e Avenues. I was the only one in the alley who had goalie equipment.

Favourite Montreal festival: Anything musical that isn’t too hip.

Favourite Montreal walk: Going up Saint-Denis as far as possible (Rosemont? Jean-Talon?) from UQAM (or the Cheval Blanc). It depends on the hour and the degree of drunkenness.

Bagel or poutine? Poutine! (Extra bacon.)

Maxime Raymond Bock was born in Montréal, Québec, in 1981. After pursuing studies in sports, music, and literature, he published four books of fiction, of which two, Atavismes (Atavisms, Dalkey Archive, 2015), and Des lames de pierre (Baloney, Coach House, 2016), were translated into English. His latest collection of short fiction, Les noyades secondaires, was published with Cheval d’août éditeur (Montreal, QC) in 2017.

Melissa Bull is Maisonneuve’s “Writing from Quebec” editor. She is also the author of a collection of poetry, Rue (2015), and the translator of Nelly Arcan's collection Burqa of Skin (2014). Her translation of Pascale Rafie's play, The Baklawa Recipe, was staged at Montreal's Centaur Theatre in 2018. Her collection of short stories, The Knockoff Eclipse, is forthcoming (2018), as is a translation of Marie-Sissi Labrèche's novel, Borderline (2019).

The interview was condensed for clarity.