Illustration by Monika Waber.

Illustration by Monika Waber.

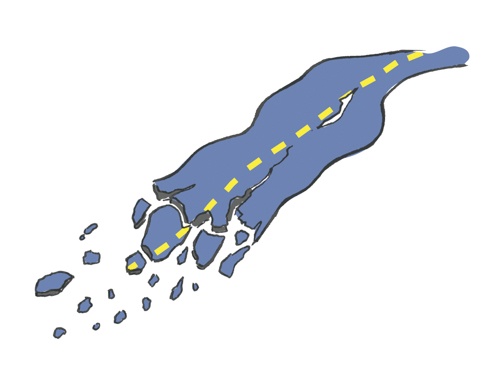

Rocks, Holes, Dynamite, Heart

Excerpts from the novel Les Murailles, translated by Melissa Bull.

I.

Tonight, I’m eating on my own like a big girl. Got to the kitchen late. There are a couple of guys hanging around but it’s not like at rush hour. I grab myself a table and plaster a willing expression across my face; I’m inviting folks to chat me up. It doesn’t work. You must think that if I wanted to talk so much I shouldn’t have sat there on my own, away from everyone. But it’s not that simple. I don’t want to bother the guy who’s just eating silently. The guy who looks at his plate like he’s out of breath, who hasn’t shaken off his day yet. He’s got to decompress. If he wanted to talk to someone he’d figure it out. So I mind my own beeswax.

I get the lasagna. I could choose either that or the chicken parmigiana. If there’s anything inedible at a cafeteria it’s always the chicken parmigiana. It’s like if you picked up some Chicken McNuggets, let them cool on the counter and then dropped a can of diced tomatoes over top and tried to disguise your mess with not enough cheese.

I realize that the casse-croute is adjacent to the caf—you could push open the wall of movable panels and make a fucking huge dining room.

I try to see who could’ve ordered the chicken. It’s hard to tell. Most of the trays are empty. They’ve opened the wall halfway. There’s a boss party on the other side. They’re talking loud, they’re laughing and there’s a big guy who raises his glass of red whenever one of his friends cracks a joke.

Four tables over I spot, across of me, the pancake-thing I’m looking for, with a side of boiled vegetables. The guy who’s eating it isn’t really eating it. He’s stabbing at the plate with his fork. That guy’s Penguin, I recognize him. He’s sitting alone, like me. I stare at him, hoping for some eye contact.

The kitchen staff shut off the portable stoves. I hear a woman complain that today’s menu didn’t take and that it’s like that every Thursday. When they have happy hour on the other side it always empties out our kitchens, she says.

The bosses are having a good time and it’s even a little over the top but you can’t blame them. They’re just a bunch of people who’ve worked a full day. Like the other workers around me, like the kitchen staff, like Penguin, who gets up so he doesn’t have to hear anymore of their fun.

II.

“So, what do you think of my roadworks?”

My uncle sobered up is a whole ’nother ball game. His eyes are creased, concentrated. He watches the road ahead and he’s as intent on the road as he was on his walk from his bed to the toilet at 3 am. He knows it, too, that he’s doing well, that he looks good. Last night he rambled on and on, but now he chooses his words carefully. He doesn’t throw around any that are too big or useless, he’s got too much respect for this. For all of this. For the rocks they blow up, the trees they chop down—you can’t think that they’re any weaker than us. Humans might have the last word but nature will fight back every step of the way. Nothing comes easy.

“Want to see some mud?”

When he shows me what they’re up to, his pride is clear. They’re not just making some forest path, they’re carving out a real provincial road that will go all the way to Labrador. People from around here will be able to drive straight there instead of taking the roundabout way, the way they do now. They’re going to save I forget how many hours’ drive.

I wonder who’s even going to Labrador?

We get a call on the CB about an oil spill. Some guy’s pick-up got a pierced tank and it’s dripping on the ground. We’ve got to go. My uncle says it’s no big deal. You just can’t get caught by the environmental crew for negligence. (“They’re doing their job but I can’t stand them.”)

Once we get there, I see the truck in question driving back and forth over the same 300 feet.

It’s so the driver doesn’t make a puddle on the ground. As long as the engine’s running, the oil drips, but it doesn’t show. My uncle thinks that’s pretty bright and tells him to keep it up ’til they deliver the new machine. He’ll take care of calling the environmental crew.

The roadworks are all around us. In some places you can guess the work to come by the way the ropes they’ve extended hang. Everything is still on gravel. It’s huge, a vast, untouched terrain.

We go by the dump and check out at all the vegetation residue and broken rocks, another huge, deforested hole that’ll be covered over in green when they’re done. My uncle tells me it makes for great fertilizer and that after while it won’t even show and then he starts up a story about my grandfather, something that always happens when we talk construction in our family.

“Your grandfather was superintendent. Comme moé,” he says. Like me.

“Yes, Maman told me. Where was he at, eh?”

“Oh, he did a bunch of places. He was in Labrador a long time.”

“Okay.”

“He was a showoff. The goddamn old guy was a showoff.”

“Haha! How?”

“Well when it was time to call the shots to the dynamiters, he always fixed it so he’d be the one on the CB. He liked giving the okay to blow things up. He always said, ‘Shoot, tabarnak! Shoot!’”

“Haha!”

“Anyway—”

I file this anecdote alongside, “Grandpapa cheated on Grandmaman with Alys Robi,” and “Grandpapa was buddies with the Great Antonio.”

The further we go, the less flat it is. Once we’re at the end of the road, I can see that there are two teams. One blasts. The other picks up. It’s a sharp slope on the bedrock. For my uncle, this is a world of possibilities, just the start of his success. Apparently there’s another gang up higher that takes care of deforestation, but we have to stay back.

“The big fucking mountain that keeps advancing on us,” he says, “watch carefully—we’re gonna make it blow.”

When we went to Tadoussac when I was little, my mother was always so proud that her father had built the dock for the ferry. As if he’d made it by himself. While we waited for the ferry, my mother told us about the times she came down from Quebec City on the weekend, when she was studying to become an aesthetician, and how my grandfather would do a round trip on the fjord just for her. Fifteen minutes to chat; cut the trajectory in two.

Today, I can understand what she felt. The mountain, the centenarian trees, the roots of the earth, the wall of rocks straight and tall … Transformed by men from home, made into a road. It’s like pulling a bus with your hair. It’s not good for much, but it’s impressive anyway.