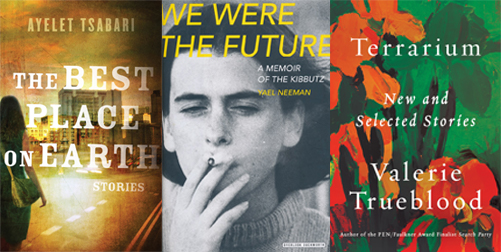

Cross-Border Conversations: Yael Neeman, Valerie Trueblood & Ayelet Tsabari

A number of years ago, I founded and coordinated a reading series here in Vancouver, the Cross-Border Pollination Readings, which brought American writers to Vancouver to read with Canadian writers. Many writers were introduced to new and appreciative audiences here, writers such as Peggy Shumaker, Camille Dungy, Joan Kane, Peter Pereira, Judith Barrington, Susan Rich, Nancy Pagh, Sam Green and Jericho Brown.

With this first interview, the Cross-Border reading series is reincarnated, transformed into Cross-Border Conversations. Without the endless hustle to find funding and accommodation for writers who come to town, these curated conversations present an opportunity to continue the work of the Cross-Border Pollination Readings, while expanding its reach across the globe. As curator, I have the great pleasure of reading these writers’ works, seeing what they have in common, and inviting them all to the figurative table. I can champion worthy books, focus on themes and subjects of particular interest, and bring together writers who may write in different genres or languages, but whose work shares similar preoccupations, writers whom I really think should know each other. These interview conversations, taking place over the course of a few days, allow a particular intimacy that would not occur any other way. They allow writers who live thousands of miles apart to talk frankly about their lives and their work, and to respond to one another’s observations. They also provide those writers who are introverts a way to reach new readers that speaks to their strengths: they can write!

This first conversation, with Yael Neeman, Valerie Trueblood and Ayelet Tsabari, brings three great short story writers from three different generations together. All three write the best kind of short stories: funny, wry, surprising gems that manage to illuminate an entire world in a few pages.

Rachel Rose: You each possess what I search for in writers: an ability to observe people and the natural world that is so devastatingly accurate, so wise, that reading certain passages in each of your books was transformative. Scenes from your books have stayed with me, permanently shifting the way I see. And yet you’ve never met, and it is unlikely you ever will, working and writing in your respective countries: Israel, America, and Canada/Israel—and two of you, Valerie and Yael, are not fond of public appearances and go out of your way to avoid them. So here we have another way to converse and connect.

What forces conspired to turn you into writers? Were their times in your life you resisted the call?

Valerie Trueblood: In a rural childhood in Virginia, the forces of Nature. Everything unpredictable: weather, the seasons, animals, from blacksnakes and chickens to dairy bulls at the State Fair. A large, opinionated, laughing family. High school. The voices of people in our county, relating the disasters that happened every day and could easily overtake you whether you deserved it or not.

I never resisted.

Ayelet Tsabari: I didn’t choose to be a writer. I just was. It came built-in. I don't remember a time before I knew I was a writer. I started telling stories before I knew the alphabet, drawing comic strips and accompanying them with narration. And I was filling school notebooks with stories and poems from grade 1. I still have piles of them, with covers I drew and synopses on the back.

I don’t know if I’d call it resistance but there were times where I was paralyzed by fear and insecurity, years in which I wrote very little and was quite miserable. Then, there was the falling into writing in another language, which wasn’t resistance, but certainly created a conflict, a diversion, an obstacle. But even that was not a conscious decision, which is why I use the word “falling into” to describe that transition.

Yael Neeman: I was a child who wrote, and was always asked and begged to do so at the kibbutz I was raised in. Afterwards, it took me many many years to recognize writing as a something that came from within me that I want to do. It was always there but completely silent. I became a writer very late in life, at around 44 (today I'm 58). It took me a long time to realize that my thoughts about things are sometimes drafts. When I recognized that, my writing became a necessity.

AT: I didn’t know that, Yael. For some reason, maybe because as an Israeli reader, I’ve known of you and your work for a while, it felt like you’ve always been around. My first book was published a few months before my 40th birthday, so it took me a while to get there too.

VT: I love Yael’s sentence, “It took me a long time to realize that my thoughts about things are sometimes drafts.” I published my first book, Seven Loves, at sixty-two, and in many ways that was a wonderful age to do it. Someone had seen what I’d been doing with my life! The years had polished away any vanity about being a writer, as a calling, but had left me with the thrill of stories, and here some of them were, between covers. It made me think of how many must be writing with that same doggedness, waiting for a reader.

RR: If you hadn’t become a writer, what might you have become instead?

VT: Maybe a naturalist. I love insects in particular, and Jean-Henri Fabre’s life in his back yard looking at them.

AT: I’m having a hard time answering this question, which obviously shows a lack of imagination on my part. A photographer? An actress? A belly dancer? These are all things I’d dabbled with in different times of my life. But during my years of not writing, my main income came from working as a waitress, a bartender and a house cleaner. I was thirty-six when I quit waitressing.

YN: Since I wasn't always a writer, I know the answer. I would be a proofreader or editor at a newspaper or a publishing house.

RR: Do you ever wish you had actually pursued that other vocation?

VT: Yes.

AT: I fantasize about a different life all the time. Different places, different choices. But I love what I do and I love my life. Maybe because it took me so long to get here, I feel so blessed and grateful for it.

YN: Not anymore, for as long as it's up to me.

RR: Tell us about your latest books.

VT: My five books have all been story collections. The latest one is Terrarium: New & Selected Stories, coming out from Counterpoint in August 2018. In it I’ve turned from the long investigations that preoccupied me for many years to very short accounts that avoid, for the most part, a firm outcome.

AT: Congratulations on the new book, Valerie! My first book, The Best Place on Earth, was also a collection of stories. My memoir in essays, The Art of Leaving, will be coming out in February 2019 with HarperCollins Canada and Random House US.

YN: My latest book was published in Israel just two months ago, and it's still very alive and fresh. It's called Once There Was A Woman. It's a portrait of an actual woman who erased everything she did in her life. She wasn't famous, although she was a gifted translator. She left no fruits behind her. She cut her head out of pictures she was in, and threw away any books with her comments written in them. She wrote in her will not to hold a memorial ceremony and not to speak of her. These are things I learned during my ten years of work on the book. The book is woven together out of interviews with thirty people who knew her from her early childhood until her death in 2002. She was born to Holocaust survivors, in a displaced persons camp in Germany immediately after the war, as were many of the interviewees. She was alone, an only child with no children of her own.

RR: What do your readers mean to you?

VT: It’s very hard to imagine readers, but the sudden letter or email, the unexpected review, the kind message from another writer—those things are lifegiving.

YN: Readers are like miracles. There's this something that I did for 10 years in solitary and it suddenly comes back to me in many varieties, through lively people.

AT: Yes, I agree with both Valerie and Yael about the miracle of readership. Whenever I feel distracted by the business of publishing, I go back to readers and what they mean and that helps ground me. I remember that I write to make people feel deeply. And that is what really matters. That said, I envy sometimes the blissful ignorance of the first book, when I wrote without knowing whether anyone will ever be reading. I am aware now of readers in a way I wasn’t then.

RR: What is the first thing you wrote that you still feel proud of?

VT: In the eighth grade I wrote a little story about a boy in Mexico who went to a bullfight, saw the bull he had raised as a calf, ran into the ring and rescued him. The story made no sense, but that was the first time my intense interest in the subjects of rescue and love burst forth.

AT: Valerie, did you ever publish this story?

VT: No! What a sweet question.

AT: In grade seven I wrote two long poems about death and my father and loss that I was really proud of. I remember the sense of accomplishment clearly. I remember feeling like these two poems displayed a richness of language and a complexity of thought and emotion that was beyond anything I’d written before.

YN: My high school graduation play. In many ways it was a prelude to my later memoir We Were The Future, (translated to English by Sondra Silverston) about growing up as part of the Narcissus collective on Kibbutz Yehiam.

RR: How do you deal with rejection, bad reviews, bad sales and other setbacks?

VT: With pain.

YN: I treat a bad review like a virus. It's still a bad virus, but you know it'll pass in a day or two, or three…

AT: It is a part of the writer’s life no doubt. I've become much better at handling rejection over the years, and I think that’s a good thing. As for reviews specifically, I happen to know two friends, both poets, one Israeli and one Canadian who don’t read any reviews. They both refer to them as “noise.” I’ve been toying with the idea of attempting that with my next book, but I’m not sure I’ll be able to pull it off.

RR: How do you define success as a writer?

VT: At this age success is keeping success and failure out of one’s mind. I do read reviews, and like seeing what’s considered successful. When I was young, rejections made me give up on publication pretty quickly, and I stopped submitting my stories until much later in life. I kept writing them, though, year in and year out! Of the writers and artists I love best, some were recognized immediately, others worked without even a witness.

YN: Many attentive readers, and not too many viruses.

RR: Do you have a literary community that is a source of strength and inspiration for you? How did you create or find that community, and how do you nurture it?

VT: I don’t have a community. I never show a draft. I have family members who are honest and always right, and two friends to whom I occasionally show a story. One of them pushed me, in my sixties, to grow up and get into the fray, and she, along with my agent Jessica Papin whose patience and soul know no bounds, have been mainstays.

When I read something I love, I write to the writer. We’re strangers to begin with, but sometimes we go on emailing for years.

YN: We created a group of five writing women, none of whom are authors but they all write. One is writing her post-doctorate about Marguerite Duras, another is translating David Foster Wallace into Hebrew, one is a choreographer and one is a graffiti artist. But these are writing meetings, and they are very fruitful for all of us.

AT: I don’t know what I’d do without a writing community. I feel fortunate to have three: one in Vancouver (where I lived for eleven years), one in Toronto, and one in Israel. The ones in Vancouver and Toronto started from attending writing programs in both cities. I made close friends whose writing I admire, and we share writing, brainstorm ideas, and support each other’s work any way we can. In Israel, for a long time I didn’t feel like a part of a writing community. I may be an Israeli writer but I’m writing in English. But after the Hebrew translation came out, I began meeting Israeli writers in various capacities, including on social media, and now have a strong group of writer friends there too. I’ve translated a couple of these friends’ work to English and they’ve looked at my Hebrew work when I needed feedback. Interestingly enough, in all three places, most of these friends are women.

RR: Were you well-mentored as a young writer? Do you mentor other writers?

VT: My Latin teacher was a mentor. In the midst of the travails of high school her class was an odd oasis, where we read the Aeneid aloud and showed all the Latin derivatives we had found in the newspaper and pasted into notebooks. I wish she were alive now to hear how much her passionate teaching has meant to me.

Then in college I had the incalculable good luck to study with both John Hawkes and John Berryman.

I correspond with young writers and want to encourage them. Encouragement gets you through some bad years! But I don’t see myself as a mentor and I don’t think they do either; it’s an exchange.

YN: I had an imaginary mentor, always. I try to avoid being an actual mentor.

VT: I like the idea of an imaginary mentor.

AT: I was lucky to be well mentored by writer Wayde Compton from Vancouver. I was ESL and very insecure when I came into his class, and Wayde was so supportive and encouraging while also providing me with tools. He was the perfect mentor at the perfect time. I can gush about Wayde all day. I also had other wonderful teachers throughout the year, like Camilla Gibb, Betsy Warland, Nancy Lee. I really can’t complain. I have been teaching creative writing for about nine years now, and the first time someone referred to me as a mentor, I felt like an impostor. But I embrace that role now, and see it as a part of giving back to a community that nurtured and supported me. I love teaching and helping young writers improve their skills and find their voice. And yes, like Valerie said, it’s always also an exchange. I learn a lot from teaching.

RR: What practices concern you most in the publishing world and the literary community?

VT: First, the disappearance or shrinkage of so many weekly book reviews. Online, of course, serious efforts go on to improve on or just plain replace print, but I miss the ink that rubbed off on our hands and gave critics and reviewers, our guides to the sea of books, a living.

Second, the fact that readers expect to encounter the writer in public now. I know, there have always been readings and tours, Dickens and Kipling toured the U.S., etc., but now accompanying your book down the aisle is an entrenched part of publishing it. A few writers really do engage happily with crowds, and they’re rightly loved for that, but for many of us, promoting a book is harder than writing it.

YN: Sometimes I feel that we're standing on a melting iceberg, and at every moment readers are jumping ship to social media or to a TV series binge and not returning to reading.

AT: What Yael said.

VT: A melting iceberg. Alas, yes.

RR: What are your current preoccupations as a writer?

VT: How to leave things out of a story. How to stop war.

YN: Since my last book is still fresh I'm busy with this strange presence of a new book. You have to transform from this lonely worker to becoming a presenter of it.

AT: My memoir in essays is coming out next winter, so I find myself thinking a lot about exposure, about the line between fiction and nonfiction, about the human need to tell our stories. I’m also in the early stages of writing a novel, and I find the scope of it terrifying. So I’m thinking a lot about structure and shape and arc. About how to find a balance between outlining, which I seem to resist because I fear it would be too restricting, and between letting go of my need for control and allowing some surprise and mystery into the process.

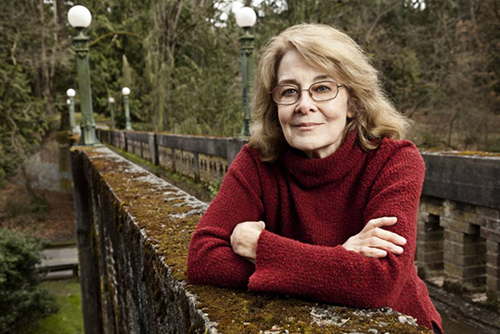

Photo credit Lucien Knuteson.

Valerie Trueblood is the author of the novel Seven Loves, and the short story collections Search Party, Marry or Burn, and Criminals. She's been a finalist for the 2014 PEN/Faulkner Award, a finalist for the Frank O'Connor International Short Story Award, and a recipient of the B&N Discover Award. She lives in Seattle.

Photo credit Jonathan Bloom.

Ayelet Tsabari was born in Israel to a large family of Yemeni descent. Her first book, The Best Place on Earth, won the Sami Rohr Prize for Jewish Literature and the Edward Lewis Wallant Award. The book was a New York Times Book Review Editors’ Choice, a Kirkus Review best book of 2016, and has been published internationally. Excerpts from her forthcoming memoir, The Art of Leaving (HarperCollins Canada, 2019) have won a National Magazine Award, a Western Magazine Award, and an Edna Staebler award.

Photo credit Tomer Appelbaum.

Yael Neeman was born in Kibbutz Yehiam, Israel in 1960. She studied for her Master's degree in Literature and Philosophy at Tel Aviv University. Her novel We Were the Future was nominated for and received awards and was a best-seller in Israel. It has been translated into French, Polish, Dutch and English. Her stories have appeared in World Literature Today and the Chattahoochee Review. She participated in the International Writing Program in Iowa City, having been chosen by the Fulbright Foundation. Her latest novel, Once There Was a Woman was published on May 2018.

Rachel Rose is the author, most recently, of Marry & Burn (poems) and The Dog Lover Unit (memoir). Visit rachelsprose.weebly.com.