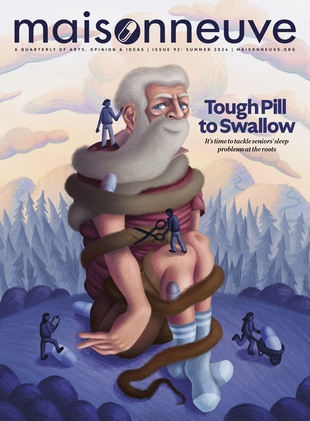

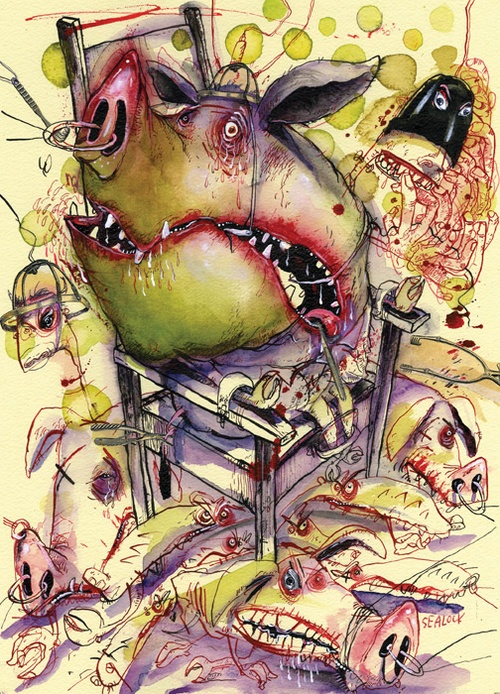

Illustration by Rick Sealock.

Illustration by Rick Sealock.

Wild Justice

A bull burned at the stake, a swarm of locusts excommunicated—animal trials were once surprisingly common.

Tilikum, whose name means “friend” in Chinook, might fairly be called a mass murderer. In 1991, he and two buddies killed a woman, each taking turns with her like it was a game, like they were just having fun. A few years later, Tilikum was found with a dead man slung across his back. The cause of death was hypothermia, but the naked corpse was covered in abuse marks, and few were foolish enough to consider Tilikum innocent. Then, on February 24, 2010, Tilikum killed again, jerking forty-year-old Dawn Brancheau into a pool by her ponytail as two dozen people looked on. According to her autopsy, Brancheau’s cervical spine had been fractured and she sustained blunt-force trauma to her jaw and ribs. Tilikum also tore off her scalp and left arm.

Tilikum is 22 feet long and weighs 12,000 pounds, making him the largest captive orca in the world. He possesses the menacing charm characteristic of all killer whales, and his dorsal fin, rather than standing straight up like a shark’s, droops to one side under its own weight. When Tilikum tore Brancheau apart in front of that small SeaWorld crowd two years ago, it was just the latest in a decade of high-profile animal attacks. In 2009, a chimpanzee named Travis mauled a friend of his keeper’s, mutilating her face beyond recognition before Connecticut police riddled him with bullets. In 2006, a stingray stabbed Steve Irwin—the Crocodile Hunter—square in the heart. In 2003, Timothy Treadwell, the engrossing, unstable subject of Werner Herzog’s Grizzly Man, was eaten by the very Alaskan bears he had devoted his life to protecting. That same year, a white tiger named Montecore pounced on Roy Horn, of Siegfried and Roy, at the performer’s fifty-ninth birthday party, seizing his trainer by the throat and dragging him casually offstage.

Over the last several years, media outlets have also reported attacks by coyotes, elephants, dolphins, alligators, sharks, water buffalo, foxes, pet cats, swans, wild dogs, leopards and, of course, pit bulls. Many of these attacks have been unprecedented in the scope of their violence; it seems that the beasts, both captive and wild, are rising up around us. In October 2011, an Ohio man released forty-eight animals from his private zoo—lions, tigers, monkeys—before surrounding himself with chicken parts and committing suicide, an event that seemed somehow logical, the fitting culmination of all this carnage. Police hunted down and killed the animals, their bloodied, exotic bodies littering the nearby fields.

The discussion surrounding these attacks has been limited to the immediate and the pragmatic. Should we put killer animals down? Should we curb tourism in places where wild things roam? Should we outlaw exotic pets, or circuses, or aquariums, or zoos? Tilikum, for one, faced no punishment for his actions; he mounted his comeback performance at SeaWorld a year later to thunderous applause (and a few beefed-up security measures). But this is not always how humans have dealt with killer animals. In the past, we have pondered their criminal agency and taken their lives in bold displays of crude retributive justice; we have wondered whether they are punishments from God or Satan’s minions. There was a time not so long ago when Tilikum, following a proper criminal trial, complete with legal representation and a judge, might have been hanged at the gallows for all of Orlando to see.

“If an ox gore a man or a woman, that they die: then the ox shall be surely stoned, and his flesh shall not be eaten,” reads Exodus 21:28. Note that the ox is executed by stoning, much like an adulterer or Sabbath-breaker would have been. And this isn’t a chance at a free meal—the brute’s criminal flesh is considered tainted. Exodus 21:28 is a biblical law like any other, and as with similar Old Testament passages about slavery and sodomy, these few short words inspired hundreds of years of human behaviour that now, from the comfort of modern retrospection, appear horrifying. In Medieval Europe, they gave rise to the animal trial: the practice of dragging a creature accused of committing a crime—like killing a child or destroying a crop—before an actual court of law, and subsequently executing, exiling or absolving it.

As outlined in E.P. Evans’ comprehensive 1906 work The Criminal Prosecution and Capital Punishment of Animals, there were two kinds of animal trials during the Middle Ages: criminal proceedings against domestic creatures accused of individual crimes, and ecclesiastical tribunals to prosecute whole groups of vermin. The latter targeted animals like mice, locusts, weevils and caterpillars for such transgressions as ruining harvests or eating food stores. (Crimes against propriety could also incur the church’s wrath; a German pastor once anathematized local sparrows after their “scandalous unchastity” interrupted a sermon.) The animals were typically tried, en masse and in absentia, and issued a date by which they had to leave town or face the unspecified disapproval of the righteous. Needless to say, the results of such ultimatums were mixed.

Ever the opportunists, some lawyers built their careers by defending animals. A sixteenth-century French jurist named Bartholomew Chassenée made his name as the counsel to some rats who were accused, in an ecclesiastical trial in Autun, of decimating the area’s barley crops. Rats being rats, Chassenée could hardly rely on his clients’ sympathetic qualities to get them off the hook. So, like numerous lawyers before and since, he built his argument on technicalities: the defendants couldn’t be expected to appear in court, as Evans says, “owing to the unwearied vigilance of their mortal enemies, the cats, who watched all their movements, and, with fell intent, lay in wait for them at every corner and passage.”

Chassenée went on to a legal career of some renown, and is said to have defended animals in many other cases. He even published a treatise, De excommunicatione animalium insectorum, on the theology and legality of anathematizing animals, in which he cited Jesus’ command to burn “every tree that bringeth not forth good fruit.” “If, therefore, it is permitted to destroy an irrational thing, because it does not produce fruit,” Chassenée wrote, “much more is it permitted to curse it, since the greater penalty includes the less.” (Jesus’ anger at inanimate objects wasn’t unique. Ancient civilizations like Greece and China would “execute” guilty items like killers’ knives or fallen statues.)

But Chassenée’s biblical logic points to a frequent tension in ecclesiastical animal tribunals: neither the jurists nor the church could ever decide whether the vermin were Satan’s hordes or the earthly agents of a vengeful God. Lawyers defending the creatures typically argued that they were holy punishments, and therefore immune to the church’s retribution; indeed, in such situations, the rats and the church would presumably be on the same team. The church agreed or disagreed depending on which was more convenient—or more profitable. In one case, during a blight of locusts in France, a refreshingly straightforward decree ordered residents to pay “tithes without fraud” and “abstain from blasphemies” until God destroyed the pests. The case was called “The People versus Locusts.”

These trials made the dubious assumption that the church—both Catholic and post-Reformation Protestant—had the power to actually expel anathematized animals. In reality, Evans argues, religious tribunals functioned primarily as a means of extending the church’s control. “If the insects disappeared,” he writes, “she received full credit for accomplishing it; if not, the failure was due to the sins of the people; in either case the prestige of the Church was preserved and her authority left unimpaired.” Of course, putting a group of insects on trial seems absurd—an obvious power grab by a greedy institution, or, more charitably, the superstition of a primitive society. The great question that the history of animal trials raises, however, is whether our contemporary relationship with animals is any more coherent than that of our forbears.

In Vanvres in 1750, a man named Jacques Ferron was caught fucking his donkey. He was sentenced to death for sodomy, a category of criminal act that at the time included having sex with Jews and Turks. In cases of bestiality, the animals were typically executed along with their human defilers; in 1685, for example, a German tailor “who had committed the unnatural deed of carnal lewdness with a mare” was burned at the stake with the unfortunate horse. But in Vanvres, the convent prior and the inhabitants of the commune signed a statement attesting to the donkey’s virtuous nature, writing that “she is in word and deed and in all her habits of life a most honest creature.” They were essentially acting as character witnesses. The donkey was acquitted; her owner was not.

A surprising number of animal trials dealt with similar instances of bestiality. In the 1600s, a Connecticut man apparently “lived in most infandous Buggeries for no less than fifty years together, and now at the gallows there were killed before his eyes a cow, two heifers, three sheep and two sows, with all of which he had committed his brutalities.” A teenage boy named Thomas Graunger was executed in Massachusetts in 1642, alongside several animals with which he had had sex. (Graunger is also said to be the first juvenile ever tried and executed in the United States.) Even today, young men who live in rural areas are more likely than their urban counterparts to have sex with animals, so perhaps it’s not so shocking that in the Middle Ages, with all those cows and pigs strutting around the commons, many peasants decided to indulge their most basic of instincts.

In contrast to the church’s excommunication of vermin, trials like these were brought against individual animals. All manner of livestock faced Medieval justice—between the years of 824 and 1845, in France alone, Evans counts 144 trials resulting in the execution or excommunication of animals, though he suggests that the real number is likely much higher. When such cases didn’t involve animals on the receiving end of a man’s amorous advances, they typically concerned those that had attacked or killed people. Pigs seemed to have some particular thirst for the blood of young children, as Evans cites several instances in which sows maimed infants; he suggests that this is because pigs roamed freely over church-owned land, providing many opportunities for such violence. In one instance, in France in 1386, the Old Testament principle of an eye for an eye was taken rather far: a sow that had bitten the face and arms of a child was mutilated in the same places before being hanged at the gallows. She was also dressed in human clothing for the execution, in some strange hint at the equality of man and beast.

Pigs awaiting trial were routinely held in human prisons; one document from 1408 matter-of-factly includes a pig in its list of prisoners and details costs such as “ten deniers tournois for a rope, found and furnished for the purpose of tying the said pig that it might not escape.” Some animals were even tortured on the rack, not in the interest of obtaining a confession but simply to observe the letter of the law. The guilty were then typically executed by burning or hanging or, most disquietingly, by being buried alive.

Animals were executed for other reasons as well—reasons that hint more explicitly at the strict religious attitudes of the time. In 1474 in Switzerland, Evans writes, a rooster was put to death “for the heinous and unnatural crime of laying an egg.” When hatched by a snake or toad, rooster’s eggs were thought to birth cockatrices or basilisks—mythical reptilian beasts capable of killing a man with a single look. Today, we might suggest that the cock was killed for the fluidity of his gender, which would put him in the same category as Jacques Ferron’s donkey or the unchaste sparrow: animals that committed “crimes” of sexuality.

Animal trials certainly solidified the church’s power, but they also made sense of an unknowable world by turning freak accidents into understandable events, with guilty parties and paths to justice. Our grain stores are gone because God is punishing us, or, alternatively, because Satan is toying with us; we must atone and pray. The pig killed my child because it is a common criminal; it must be punished. In this sense, animal trials were not unlike that other great, barbaric version of rudimentary legal justice: the witch hunt, which also reckoned with inexplicable phenomena by targeting scapegoats. Indeed, Evans writes, during witch hunts animals were often punished alongside all those single women and healers, in keeping with the belief that Satan commonly possessed creatures like goats, ravens and porcupines.

Animal trials began to die off when Enlightenment ideals shouldered aside physical torture in favour of psychological penalties: lifetime incarceration, death row, jokes about dropping the soap. As European legal systems sought to fashion themselves as something other than instruments of naked state coercion, prisons grew less physically brutal and started relying on subtler, more emotional methods. Foucault famously theorized that, during this period, the locus of punishment shifted from the prisoner’s body to his soul. And so, because animals have no soul to break, we stopped forcing them through the courts. In animal trials we see our churlish early efforts at an institutionalized criminal code. It’s like watching a child play house.

Though most animal trials ceased after the Enlightenment, there are a few more contemporary examples. In 1877 in New York, for instance, an organ grinder’s monkey injured a woman’s hand and was placed under arrest. “I do not think I can legally commit him,” the judge said, according to the New York Times, to which the woman indignantly replied, “And is there no law for monkeys?” But there is a still stranger case, one in which—like the similarity between animal and witch trials—cruelty toward a beast mirrored the era’s cruelty toward human beings. On September 13, 1916, the good people of Erwin, Tennessee lynched Murderous Mary the Elephant.

The early twentieth century was the golden age of the travelling American circus. Barnum and Bailey was the largest and most famous operation, but countless smaller circuses also roamed the country by rail. Not yet sullied by animal-rights protests or refashioned as highbrow entertainment, circuses were still exotic and democratic, places where even poor small-town Americans could see things they never thought possible: trained tigers, painted horses on parade, “educated” sea lions, clowns. And then there was the main attraction, the strangest and wisest animals on the planet: the elephants.

Sparks World-Famous Shows was a small operation with a big draw: a female Indian pachyderm called Mary. Posters advertised Mary as “the largest living land animal on Earth,” which could not possibly have been true. Indian elephants are kept in captivity because they’re smaller and more trainable than their African counterparts, and females are considered more even-tempered than males. Still, Mary had a nasty streak. Killer elephants were not uncommon, and were often sold from circus to circus, renamed each time to fool the frightened rubes. Rumour had it that this particular elephant had taken the lives of as many as twenty people already; eventually, she even earned the nickname Murderous Mary.

On September 12, the Sparks circus arrived in Kingsport, Tennessee. Following a successful performance, the elephant trainers walked their five charges through town to a pond, so that the animals could drink and cool off. A man named Red Eldridge, a new recruit and an inexperienced trainer, was riding Mary. According to Charles Edwin Price’s The Day They Hung The Elephant, Mary reached down with her trunk for a discarded melon rind, and Eldridge, eager to keep moving, smacked her on the head with his stick. A local newspaper reported what happened next—likely with more than a hint of exaggeration. The elephant

suddenly collided its trunk vice-like [sic] about his body, lifted him ten feet in the air, then dashed him with fury to the ground. Before Eldridge had a chance to reach his feet, the elephant had him pinioned to the ground, and with the full force of her biestly [sic] fury is said to have sunk her giant tusks entirely through his body. The animal then trampled the dying form of Eldridge as if seeking a murderous triumph, then with a sudden...swing of her massive foot hurled his body into the crowd.

A local blacksmith fired a few rounds at Mary, to little effect. Eldridge’s corpse was by now a gruesome sight; according to a 1993 article in Blue Ridge Country magazine, one eyewitness said that “blood and brains and stuff just squirted all over the street” after Mary stomped her enormous foot onto Eldridge’s skull. Circus workers eventually regained control of her, but not before the crowd had begun an ominous chant: “Kill the elephant.”

Much like another multi-ton serial killer that took its trainer’s life a century later, Mary was a valuable animal, worth somewhere between $8,000 and $20,000. She was dangerous, but she was also Sparks’ chief attraction. That very evening, she performed as scheduled under the packed big top. But the people of Tennessee wanted blood. The mayors of Johnson City and Rogersville, two towns where Sparks was booked to perform later that week, both announced that they’d never let a killer elephant inside city limits. Charlie Sparks, the owner of the circus, had to do something.

In keeping with the mores of Southern justice, he settled on a hanging. Ever the showman—his father had run the circus before him—Sparks perhaps realized what a spectacle that would make: far better than gunning the beast down would be breaking her neck and leaving her to swing in the Tennessee breeze. Think of the publicity. And he wouldn’t charge a dime.

Poor guilty Mary must have known what was coming; when the circus pulled in to nearby Erwin on September 13, the matinee show proceeded, but Mary herself was chained up out of sight, swaying nervously. That afternoon, Price writes, three thousand people streamed into the railyards. The circus workers had brought along the rest of the herd, hoping to ease Mary’s walk down death row. After they chained Mary to the rails, the men drove the other elephants away. But the animals seemed to understand what was about to happen, Price suggests, and they all began trumpeting as though in prescient mourning.

A cable and chain, dangling from a 100-ton Clinchfield Railyard crane boom, was slipped over Mary’s neck. The operator threw the motor into motion, and the derrick reeled in the chain, squeezing the elephant’s throat and lifting her from the ground. Mary twisted in agony; there was a sudden snap, and she crashed back to the earth, all 10,000 pounds of her, sitting there stunned and reeling with a broken hip. Some of the crowd scattered. But the job had to be finished. Mary’s executioners attached a heavier chain and tried again. This time it worked, and Mary finally died like the captive she was, with metal around her neck and a crowd looking on in awe and horror.

This wasn’t an execution; it was a lynching. There was no trial to speak of. But the death of Murderous Mary has its place in the history of animal trials because it reflected the values of its age. In the Southern US, this was the era of lynching. In Tennessee alone, an estimated 204 black people were lynched between 1882 and 1968, according to the Tuskegee Institute—a number that rises to 3,446 nationwide. It was a time and a place in which this particularly cruel form of justice was meted out with no regard for due process or fair hearings. Medieval Europeans thought animals deserved trials; to the Tennesseans of 1916, on the other hand, an elephant lynching was just like any other. Animals didn’t deserve trials before their executions, but then again, neither did men.

What were Medieval Europeans thinking when they executed a bull or anathematized a pack of rats? Did this really seem like justice served? The most bizarre aspect of the whole strange phenomenon is the fact that it put man and beast on nearly the same level. Killer animals weren’t merely disposed of; they were processed through the machine of justice, however puerile it was, just like human criminals. Some, like the unlucky French pig, were even dressed in human clothes. Animal trials were rooted in religious doctrine, and yet, in Genesis 1:26, God says, “Let us make man in our image, after our likeness: and let them have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the earth, and over every creeping thing that creepeth upon the earth.” We are made in God’s image, and we have authority over the entire world. So why did the pious people of fourteenth-century France and Germany treat animals—criminal animals, no less—as if they were human beings?

In his introduction to the recent book Fear of the Animal Planet, the left-wing journalist Jeffrey St. Clair offers one explanation. The people of Medieval Europe, he writes, “presumed that animals acted with intention, that they could be driven by greed, jealousy and revenge. Thus the people of the Middle Ages, dismissed as primitives in many modernist quarters, were actually open to a truly radical idea: animal consciousness.” St. Clair suggests that, unlike humans today, prosecutors in animal trials granted beasts “rationality, premeditation, free will, moral agency, calculation and motivation.” But surely this is wishful thinking. In ascribing such broad-minded empathy to the people of the Medieval West, St. Clair ignores the evidence to the contrary: vermin were frequently assumed to be mindless tools of Satan, for example, and “consciousness” is a bit of a murky idea. Jews and Turks and witches presumably were conscious too, but this did little to save them from being sent to the stake along with the beasts. Anyway, would St. Clair say that a weevil is capable of moral agency or free will?

Where St. Clair might be on to something, though, is in his refusal to let us off the hook in our contemporary relationship with animals. The vegetarian’s best argument has always been that of incoherence: Why are rabbits cute but rats revolting? Why do animal-cruelty laws protect pets but exclude livestock? The vegetarian’s answer, in turn, is to make our connection with animals more consistent: don’t kill them for food, don’t wear their skins, don’t torture them in the laboratory. And then, of course, more difficulties come up. What about indigenous hunting traditions or organic farming? What if testing drugs on apes could lead to a cure for cancer? Is it okay to consume honey, or is it simply wrong to enslave bees, brainless insects though they are?

In this light, animal trials begin to look less ridiculous. What’s absurd is the idea of trying a creature that has no moral compass, no ability to differentiate between right and wrong or atone for its actions. The outcome, though, is just as brutal as any factory-farm operation: an animal led to a painful death for reasons it cannot possibly discern. Ultimately, the problem of animal trials is the problem at the heart of the relationship between humanity and the natural world: do animals exist for our use? If the answer is no, then what gives us the right to eat or destroy them? If the answer is yes, then why does it matter whether we kill them in a slaughterhouse or at the gallows? The animal doesn’t know, or care, whether we are punishing it for some crime or killing it for its meat, and any concern over the difference merely reflects the narcissism of human morality.

Despite millennia of coexistence and co-dependence, despite centuries of scientific study and decades of psycho-behavioural analysis, the truth is that we don’t know very much about what animals think. We don’t really know which animals, if any, are capable of moral judgments the way we are; we can’t feel the extent of their suffering at our hands. The act of studying an animal remains impossible to separate from the act of anthropomorphizing it, and no matter what clichés we spout about the innate intelligence in the gaze of a chimpanzee or an elephant, we don’t know what’s happening in their big, childlike brains. You can look into an animal’s face and see anything you want: great unknowability, dull stupidity, wisdom, compassion. We say that dolphins are smart, but their eyes are still just black beads, as impenetrable as those of a snake or sparrow.

If we’ll never be able to sort out our relationship with animals—what the anthrozoologist Hal Herzog calls our “moral inconsistency”—then does any of this matter? Should we just put Tilikum and his killer ilk on trial for the hell of it? Of course not. The history of animals and the justice system complicates the question of how we share the planet with other species, but it shouldn’t lead to moral nihilism. We still have responsibilities toward animals, and a lot of room for improvement. And, in any case, that history is hardly over. In 2011, People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals sued SeaWorld on behalf of five captive orcas, including Tilikum, arguing that the whales were being held in slavery or involuntary servitude—an alleged violation of the Thirteenth Amendment. (St. Clair calls Tilikum “the Nat Turner of the captives of SeaWorld” who “struck courageous blows against the enslavement of wild creatures.”) A judge ruled against the plaintiffs earlier this year, saying that the Constitution applies only to humans. For now, Tilikum, simultaneously a murderer and a captive, remains behind bars of plastic and chlorine, awaiting a day in court that will never come.