Illustration by Gracia Lam.

Illustration by Gracia Lam.

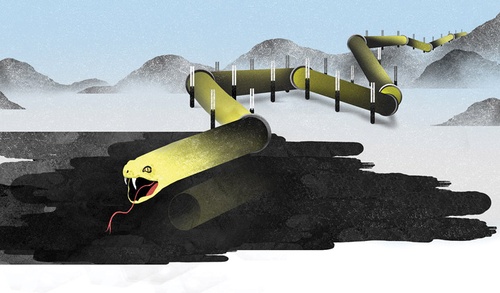

The Tar Sands Trap

What if natural-resource booms are actually bad for the Canadian economy?

ON MARCH 18, ALBERTA PREMIER Alison Redford delivered a speech to the Economic Club of Canada skewering federal NDP leader Thomas Mulcair for his dismissal of the Keystone XL pipeline’s potential economic benefits. Mulcair had visited the US a week prior, and spoken out against Keystone XL; in 2012, he had publicly wondered whether Alberta’s tar sands were causing “Dutch disease”—the decline of manufacturing due to a currency overvalued by a natural-resource boom—in Canada. In response, Redford lashed out, calling Mulcair’s remarks a “fundamental betrayal” not just of Alberta but of the entire country.

Over the last few years, a steady stream of federal cabinet ministers has joined Redford on frequent trips to Washington to lobby for the approval of Keystone XL, which could send 830,000 barrels of unprocessed, carbon-intensive bitumen to the US each day. The prevailing logic: increasing exports of a resource staple like oil is a stable path to long-term growth and prosperity for all Canadians. Opposition to the Alberta tar sands usually focuses on their enormous ecological footprint, but, as proven by the backlash that Mulcair faced, there’s considerably less skepticism toward the idea that oil is a boon for the Canadian economy.

The embrace of oil-fuelled growth has not come about in a vacuum. According to the Polaris Institute, oil- and gas-industry lobbyists had over 2,700 communications with the Canadian government between 2008 and 2012—more than any other interest group. The government consulted extensively with the energy industry before it “streamlined” Canada’s environmental regulations in the 2012 omnibus budget bill, which gutted the Environmental Assessment Agency and the Navigable Waters Protection Act. Prime Minister Stephen Harper’s major public-policy initiatives betray an obsession with a staple-led export growth strategy, in which files as diverse as energy, the environment, Aboriginal issues and foreign affairs are moulded to promote the tar sands. It’s clear that the Harper government is beholden to the oil sector.

What if Mulcair is on the right track? Our policymakers’ focus on resource exports risks trapping us in a precarious economic situation—one in which Canada not only becomes more vulnerable to volatile fluctuations in the price of oil, but in which we sacrifice innovation and the development of other areas of the economy at the altar of short-term profits from the bitumen rush. In fact, this is a scenario that eminent political economist Mel Watkins believes is a chronic Canadian condition. Forget “Dutch disease”—he calls it “Canadian disease.”

The story of Canada’s economy is one of successive resource booms exploited for export to more advanced industrial centres like Britain and the United States. We fished cod from the sea, hunted the beaver to near-extinction, turned the prairies into a breadbasket, logged the forests for timber—and watched our staple goods disappear across our borders.

This approach to understanding Canadian history rests on the scholarship of one of Canada’s most celebrated thinkers: Harold Innis. The exploitation of resources, Innis observed, creates linkages and blockages throughout the economy, but particularly in the regions where staples are located. Resources shape how and where land is settled (or appropriated from indigenous peoples), determine the transportation and communication networks that are built and influence the political institutions that form. For example, according to Carleton University political economist Brendan Haley, Innis’ work traced how the fur trade helped carve Canada’s borders, and how wheat development led to the rise of the railroad system.

Canada’s legacy as a hewer of wood and drawer of water was the subject of much heated debate in the sixties and early seventies. As a young professor at the University of Toronto, Mel Watkins made his mark in 1963 with a landmark article called “A Staple Theory of Economic Growth.” In it, he coined the term “staples trap” to refer to the inability of a resource-based economy like Canada’s to mature into a diverse, industrialized one. Overspecialization in the export of unprocessed commodities, he argued, meant depending on foreign direct investment. It’s a strategy that he believes impeded the development of Canada’s domestic manufacturing sector.

While ample in boom times, revenue from staple exports is vulnerable to changes in technology, taste and other unpredictable forces in foreign markets. In the nineteenth century, for example, Upper Canada installed canals to facilitate the export of timber and wheat. But these massive investments bankrupted the government when railroad technology rendered the canals obsolete, and when demand for wheat dropped dramatically following Britain’s abolition of its preferential commercial relationship with the Commonwealth.

With massive capital outlays being sunk into new tar-sands projects, Watkins’ ideas are more timely than ever. In an interview, he explains that “there is nothing wrong, per se, with exporting resources.” But the problem comes from what Innis referred to as the “stamp” that each staple leaves—the inhibiting mentality it fosters among political decision-makers. This is classic “Canadian disease.” Governments, Watkins says, are drawn by “the lure of quick riches” and cozy up to the “staples fraction of the business class”—a corrosive relationship that skews how resource exports are integrated into Canada’s broader economic strategy. “Mel is quite right to call what we have ‘Canadian disease,’” says Kari Levitt, the author of a seminal book of Canadian political economy, 1970’s Silent Surrender. According to Levitt, close links between the Canadian finance and resource sectors—created primarily through investment in capital-intensive transportation networks—resulted in “an indigenous capitalist class with a short-term view to profitability.”

York University political scientist Daniel Drache says this near-sighted profit chasing is worsened by the “fragmentation and balkanization” of Canada into competing economies. Staples, by their nature, tend to be regionally based and lead to geographical disparities. In Canada, Drache says, this has turned into a crisis of federalism, with every province trying to outbid each other at the expense of robust national strategies. This is why we see, to take one recent example, the premiers of Alberta and British Columbia jousting publicly over how to split the spoils of a pipeline.

Critics of the staples-trap theory argue that it overemphasizes the importance of resources like oil to the Canadian economy. Canada’s energy sector, for example, accounts for less than 5 percent of our Gross Domestic Product. Consequently, they say, the staples trap overstates both the impact that our energy exports have on other economic sectors and the degree to which Canada’s economy is vulnerable to shifts in global demand for oil. Mark Carney, the outgoing governor of the Bank of Canada, recently called the strength of our resource sector “a reflection of success, not a harbinger of failure.” He firmly dismissed the notion that Canada was experiencing Dutch disease, attributing our manufacturing losses to a “broad secular trend across the advanced world.”

But Haley sees the government’s fixation on the energy sector as a key sign of the staples trap. “They view the oil sands as the only pathway for Canada to follow,” he says. “It shows they have a staples mentality.”

According to Haley, the staples trap isn’t necessarily about calculating the percentage of energy exports in Canada’s GDP. The issue is whether reliance on staples impedes policymakers’ ability to create more resilient, transformative economies. Indeed, a 2012 Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development report attributed Canada’s regionally unequal growth to high commodity prices and called on the government to invest in other areas of the economy—an implicit endorsement of the Canadian-disease thesis.

Faced with soaring youth unemployment, worrisome deficits in skilled trades and lagging innovation and productivity indicators, one might expect the federal government to develop economic policies that look beyond the pursuit of new markets for Alberta oil. It’s precisely this lack of attention that demonstrates the staples mentality at work.

What is to be done? The traditional path out of the staples trap, proposed by economists like Watkins, was to strengthen the economy by investing in industries that add value to resources, rather than exporting them raw. Applied to the tar sands, for example, this would involve boosting Alberta’s capacity for upgrading and refining. But Haley sees this as a dangerous option in light of the global climate crisis; the inevitable transition to a low-carbon economy will create incentives to keep tar-sands oil underground. “You can add value to the horse and buggy,” he says, “but if no one wants to use the horse and buggy anymore, it doesn’t matter.”

Harold Innis was fascinated with staples because he saw them as “storm centres” of the global economy: commodities that illuminate much larger economic dynamics. Is it really prudent to tie our future growth and prosperity to a twentieth-century staple like oil? Should we not be building a green economy that prepares us for a low-carbon future? If Canada is to carve out an alternative to the Harper government’s economically uncertain and ecologically destructive path, we’ll have to start by finding a cure for our national illness.