Teo Zamudio

Teo Zamudio

An Excerpt from New Tab

From the Montreal-based writer's first novel, out this month.

Montreal-based writer Guillaume Morissette’s first novel, New Tab, is out this month through Vehicule Press. Semi-autographical in nature, the books is set in Montreal and centered around a twenty-six year old videogame designer who’s trying to reset his life.

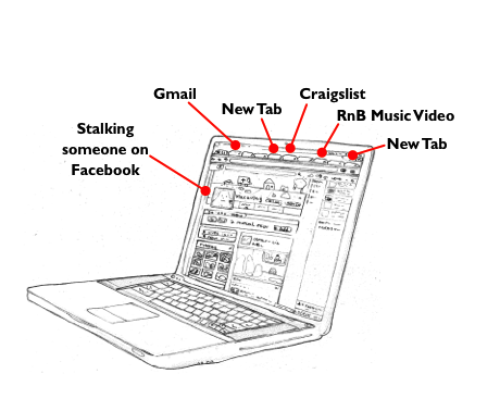

Stalking Brent on Facebook, I saw from his profile picture that he was tall and had sloppy bed hair that randomly looked excellent and that he owned a MacBook and a t-shirt that said “RIP DJ Screw.” I looked for a birth year but there was no year specified, just a month and a day. I didn’t know if he was younger than me or maybe my age. I wanted him to be my age. I wanted him to be ten thousand years older than me. I wanted him to be ten thousand years older than me and still a mess and still thinking things like, “I am the shittiest person alive,” on a regular basis.

That year, I kept meeting people who I thought were my age but then turned out to be younger than me. Brent was a good example. He was a fully-grown human person, looked like more of a dad than I ever would, but then somewhere in my thought process I felt the defeating certitude that Brent was, in fact, a year or two younger than me.

It was confusing information to handle.

“Mid-twenties and not insane and drama-free,” is how I had described myself to Brent over email. His email address ended with the domain name of a local arts and culture festival. His Craigslist ad had said that he was an independent filmmaker who was sharing a house with an art student and an “awesome guy trying to figure out life.” They had a room available and I had a person available. Just from the emails with Brent, I already felt good about it and like I wanted to take it.

Later that day, I received two emails from him in the span of maybe an hour. The first email was to ask me when I could come by to visit and the second email was to tell me they had filled the room and that it wouldn’t work out. Brent explained that they needed someone right away and that a person had offered to pay cash if he could take the room immediately. Staring at Brent’s second email, I felt doomed. I never had good timing, wouldn’t luck into a new living situation I would like, would just end up settling for one that I thought was okay but then would eventually grow to loathe, with no one there to teach me how to have sloppy bed hair that randomly looks excellent.

Then I thought, “It’s December, everyone feels doomed in December.”

*

This is how it felt: I still had some leftover youth, but by that point I had lived enough years, enough decades to feel like I wanted reality to go away for a while, make me miss it a little.

Reality was a kind of insomnia, always there, just there, annoyingly there, in my bed, at the park, inside every raccoon, behind movie stars in movie trailers, there, being, occurring, fluctuating, not telling me what it wanted from me, giving me the silent treatment, a kind of torture. “What?” I wanted to scream at it. Closing my eyes didn’t make it go away, because what I saw then wasn’t the absence of reality, it was only closed eyelids.

There was nothing I could do to hurt reality. I couldn’t set it on fire, couldn’t put it up for auction on eBay, couldn’t pump it full of helium and then wave it goodbye while driving away in a lime-green Jeep Wrangler. I couldn’t separate myself from reality. I would always be trapped within.

It was a terrible sensation, though only when I thought about it.

*

“We’re just off of St-Dominique and Mont-Royal,” read Ines’ third email, “but we also have a bit of an evil situation right now. I’ll explain in person. I hope that’s okay.”

“That’s okay,” I typed. I was sitting on my bed with my back resting against a pillow. It was the third week of January. The laptop was testing my thighs’ resistance to heat. The pillow was rectangular and the computer screen was also rectangular.

“I could come by on Sunday if you want,” I typed. “Maybe two p.m.”

About half an hour later, I received a response email from Ines to confirm the time and date. I closed two browser tabs, looked at the cropped heads of people on Facebook for a while, didn’t feel optimistic about going to see another room, didn’t feel anything. Two days before, I had visited an overly communal eleven and a half. One of the roommates there had seemed excited that I owned an Xbox 360, because he also owned an Xbox 360.

“I got so smashed last night,” read a Chat message from Shannon on Facebook. “Oh my god. I need an IV bag. Plug it in my brain, through my nose.”

“I kind of wish I was regretting last night right now,” I typed back. “I didn’t get your text until this morning. My phone fucked me over. I would have come.”

“I am never going out again,” typed Shannon. “I kind of want to go out tonight. But maybe I need to stay in and watch that movie I bought when the Blockbuster closed down. I still haven’t watched it.”

“I might just hide in my room tonight,” I typed. “I can’t decide if that’s Zen or depressing.”

“Is it really four?” typed Shannon. “I don’t know if I trust what time now is.”

“I know what you mean,” I typed. “Winter is terrible. Every day feels vaguely like a Wednesday, and any time of the day feels vaguely like four p.m.”

“The Concordia website makes no sense,” typed Shannon. “No sense at all. I need the form for the external credit thing but I’ve looked everywhere and it’s not everywhere I’ve looked.”

“Most of the time, I just google ‘Concordia’ and then the thing I am looking for,” I typed. “Google finds it. Concordia’s search engine is programmed to hate people. But it’s not its fault. It’s the programming’s fault.”

“One of these days I am going to ram my car into Concordia,” typed Shannon. “Not voluntarily or involuntarily, more like, I’ll just let it happen.”

“I would defend you in court,” I typed. “It was provocation, I would say.”

“You could say I was messed up at an early age,” typed Shannon, “by my kindergarten teacher. She asked us to draw something starting with the letter W, so I drew Wakko from the Animaniacs. My teacher said I had made that up. She made me draw a whale. A stupid whale.”

“That’s funny,” I typed. “On Thursday, someone in my creative process class asked the teacher what you can do with a creative writing degree. He said, ‘Nothing,’ and then laughed. Other people laughed nervously.”

“That’s true,” typed Shannon. “I mean, our lives are poorly planned. Realistically, I don’t know how I’ll be hired for anything after I graduate. If you’re a girl, it’s even worse. All the women poets seem to end up locked in asylums or offing themselves.”

“We should give up while we still can,” I typed. “Move to Sweden, change both our first names to Knut.”

“It’s tempting,” typed Shannon.

“In November, I met this guy who works at Blizzarts,” I typed. “He had just graduated as an English lit. major. His boss didn’t expect him to write essays that questioned things. His boss wanted him to cut lemons.”

“Ugh,” typed Shannon. “I don’t understand why people aren’t more concerned about this. They spend all their time instead being catty and backtalking other people’s writing.”

“Do you think people in other programs are less insecure?” I typed.

“People in Fine Arts are probably like, ‘Did you see the abstract shapes that this bitch submitted to class? I hate that bitch,’ ” typed Shannon. “No, you’re right. It’s probably the same thing.”

*

As a human being, I wasn’t good at anything obvious, didn’t foresee a direct path like, “I can paint, so I am going to be a painter.” I could think interesting things from time to time, but then how should the thoughts be used? I could be inventive just as much as I could be a disaster. My skill set was still a complete mystery to me, felt like a rarely observed phenomenon, something that could be just a fluke or an elaborate hoax.

*

Meeting fully grown human beings with ridiculous, implausible birth years was starting to impose itself as the default mode of meeting new people.

*

On certain days, it seemed like one hundred percent of what I looked at on the internet was, when I thought about it, deeply embarrassing.

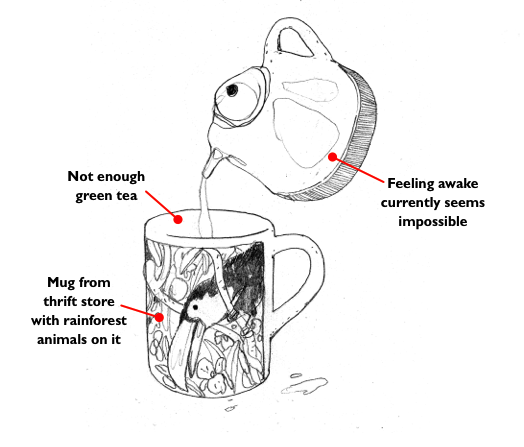

I made tea in the kitchen by pouring hot water on a white bag in the shape of a trapezoid. It was ten a.m. Coming through the window was a kind of trembling light, as if nervous a little, afraid to get yelled at or scolded. I couldn’t get myself to feel awake. I would never feel awake. I thought about dynamiting my leg to feel awake. I didn’t have dynamite.

I heard two of my roommates moving around in their rooms. Our apartment was maybe eighty percent hallways, with rooms spread out far apart from one another, making it easier for us to avoid each other than to hang out. This was okay, as I was more comfortable with their absence than with their presence. They were all, like me, French Canadian. Two of them had jobs and complained about them and sometimes had people over, to complain about other jobs than theirs. One, unlike me, had separatist ideals and a romantic attachment to French Canadian culture. I think she resented me a little for not voting and not being proud by default of my cultural heritage and for having applied to an English-speaking university instead of a French-speaking one. What we both didn’t understand at the time was that switching to English as a primary language was just a practical way for me to reinvent myself.

I had lived there for about a year in my first apartment in Montreal, felt ready to move out, wanted those people, my roommates, to no longer be people in my life, just memories, abstractions in my head locked behind some sort of mental door labelled, “Caution, harmful radiation, do not open.”

In the metro maybe two hours later, I read about twenty pages of The Hour of the Star by Clarice Lispector. In the novella, an unhappy person seemed unable to perceive herself as unhappy. I got out at the Mont-Royal station and walked with my head down, watching my feet compress snow. Around me, wind felt overexcited, eager to be elsewhere, moving things around as if trying to solve some sort of imperceptible puzzle. I blew heat onto my fingers and then couldn’t think of a good reason that justified not wearing mittens.

I turned on St-Dominique and passed a garage door with purple graffiti on it that said “Ghostbusters.” I found a white door located at ground level with the address I was looking for above it. Scotch-taped to the door’s window was a cut-out article from a local newspaper about what looked like a local independent short film I had never heard of. I knocked and then thought about rearranging my hair and then regretted knocking right away and then someone opened the door. A person wearing a beige blouse with butterflies on it greeted me and introduced herself as Ines. “Thomas,” I said. My own name echoed in my head. I tried smiling but couldn’t produce something high enough for it to be a smile, just a kind of weird mouth extension, something I could take back, pretend had never happened, my little secret.

I entered, removed my jacket and winter things. Ines guided me around. She listed the pros and cons of each room and explained the rent system and the electric-bill system. There was a large bedroom, an average-sized bedroom with a walk-in closet, a small bedroom with natural light but no closet, a small bedroom with no natural light but a closet, a common area, a kitchen, a bathroom. The residence didn’t feel like an apartment so much as a house, except maybe narrower, as if it had been, somehow, deflated, to occupy less space, like an air mattress.

“Our internet is free,” said Ines. “There’s a Wi-Fi signal somewhere around that’s not protected. At first, Cristian was like, ‘Don’t use it, it’s a trap.’ He thought it was too good to be true. But then we started using it anyway and nothing happened, so we just kept going.”

Behind the building was a medium-sized backyard that contained a depressing amount of snow, a metal staircase that spiralled like a pig’s tail, a shed, what looked like stacks of chairs unlikely to survive winter, and a plastic flamingo, though its body was submerged and only the head was visible. I wasn’t expecting a backyard at all, so I was kind of impressed by it.

In the area, most buildings didn’t have backyards, just touched each other uncomfortably instead.

“In the summer, we sometimes use the space for movie screenings,” Ines said. “It’s great.”

Looking into the backyard again, I noticed a homemade movie screen made from two by fours and a large piece of cloth. I glanced back at Ines. She smiled. I thought about how she had been smiling a lot, easily and naturally, as if for her that didn’t require any effort at all. I felt jealous a little. We walked back to the common area. Around us were a cat clock, a square pillow with kittens on it, Christmas lights, a stained couch, a small television monitor, a thermostat with a cat sticker on it and about thirty miniature stuffed jellyfish hanging via strings from the ceiling. Ines explained the jellyfish were originally a project for school. I remembered her mentioning over email that she was a studio arts major.

We sat down. I thought about the jellyfish. I wasn’t sure what a group of jellyfish was called. I thought, “A crew,” but then didn’t think that was correct. “A crew of jellyfish.” I noticed my stress level was low, which was good, and that I didn’t seem to be feeling uncomfortable or self-conscious. In the past, the process of being interviewed for a room had made me feel like I was being observed and judged and critiqued and, overall, as if a dog in a dog show.

“So another thing I need to explain is why we have a room available now,” said Ines.

She paused and placed her hands on her lap.

“I don’t even know where to start,” she added. “We have to kick Dan out. He’s the evil situation I was talking about. He moved in a few weeks ago but he’s being really creepy. We’re scared of him now. He’s forty. Dan’s forty.”

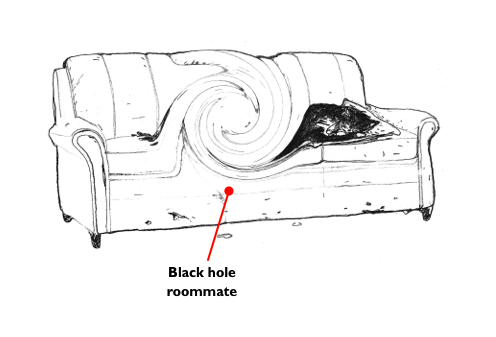

Ines explained that Dan worked two days per week doing something no one understood. On most days, he sat on the couch, ate salted crackers, monitored the small television monitor, complained a lot. He was impossible to avoid.

“He’s like a black hole,” said Ines. “The sexist shit he told me, it’s unbelievable. He also got into a screaming argument with Cristian about something. Cristian is never stressed or angry about anything, so I don’t even know how he did that. We just don’t want to have to deal with him anymore.”

Trying to visualize Dan, I thought, “Black hole.” I pictured a large celestial object hovering five inches above the stained couch, devouring time, matter and space, watching judgmental daytime television, seeking life advice from the commercials.

“How did you find him?” I said.

“Our other roommate is in South America for two months,” said Ines. “He’s the one who interviewed him. Dan was willing to pay cash right away so he said yes. When Dan moved in, we immediately thought that there was something wrong with him. He had a bag of dirty clothes and that was it. He was like, ‘Do you guys have a mattress for me?’ We had one but it was like, how can you be forty and not own anything?”

Ines paused again. She added that she thought Dan had maybe just got out of prison.

“But he’ll be gone before the end of the month, so you don’t have to worry about that,” said Ines. “Right now, living here, there’s me, Cristian and Niklas, who’s subletting. Niklas is twenty and from Germany. He’s adorable. It’s his first time living by himself. He wanted to get life experience before starting university in Germany, so all he does is go out and party a lot. There’s also Brent, who Niklas is replacing for now. Brent is amazing. He’s the one in South America.”

“Wait, is he a filmmaker?” I said.

“Yes, do you know him?” said Ines. “His last name is Cole.”

“I think we emailed,” I said. “That’s funny. I replied to his ad a few weeks ago. He wanted me to visit. Then he emailed me again saying the room was filled. That was probably Dan.”

“And you found your way back,” said Ines. “Like a lost cat. That’s amazing. Meant to be.”

“It’s like a bad John Cusack movie,” I said.

Ines laughed a little. I thought, “Bad John Cusack movie,” and then, “John Cusack movie,” and wasn’t sure I could tell the difference. I didn’t know if Ines was laughing politely or had understood that I was referring to the movie Serendipity. In the film, a series of highly improbable coincidences allows John Cusack to reunite with a person he wants to have sex with. “It’s romantic,” a girl I had watched the movie with had told me in defence of it. After that movie or some other movie, I had stopped watching movies altogether. I wondered if the true purpose of me watching Serendipity with John Cusack was to make an awkward offhand reference to it many years later in an earnest attempt to convince Ines that I was not a deranged person and that we should live together.

“What about you, what’s your situation?” said Ines. “You said you were at Concordia.”

“I am,” I said. “I just started school again. I am only part-time for now, though. I am not on loans or anything, so I also have a full-time job.”

“What do you study?” said Ines.

“Creative writing,” I said.

“That’s cool,” said Ines. “Your English is good, you just have a little accent. Because of your last name, I wasn’t sure if you were going to speak French or not. We mostly communicate in English. Cristian can speak some French, but he only really uses it at work. I am from Edmonton originally, so I only know a few things. Permettez-moi, monsieur. Le petit gâteau. La mer Morte.”

“I am bilingual, so it should be fine,” I said.

“That’s what I figured,” said Ines. “You go to Concordia and stuff.”

She paused again. I rearranged my hair with my hand. Looking directly at Ines, I noticed a shine in the upper section of her right eye. It looked photoshopped in, as if the shine was on a layer above the eyeball.

“So,” said Ines. “Do you have more questions?”

“No,” I said. “I think I am good. Do you have more questions for me?”

“Yeah,” said Ines. “Do you want the room?”

“I think so, yeah,” I said.

“That’s great,” said Ines. “I really don’t want to interview a million people and you seem fine. My email inbox right now is filled with weirdos telling me their life stories and then asking me for directions on how to come here. We haven’t told Dan that he’s getting kicked out yet, but this week, Cristian and me are going to sit down and drink beers and talk ourselves into it. We’ve been avoiding it, like I am scared he’s going to flip his shit. He might get violent and break stuff.”

“Maybe he’ll break something from his room,” I said.

“He doesn’t have anything,” said Ines.

“He could flip the mattress over,” I said. “Stab it with his keys or something.”

“I don’t know what he’s going to do,” said Ines. “When I was a kid and I had to do something I was scared of doing, my mom used to hand me a piece of paper and a pen and tell me, ‘Draw courage,’ and then I would draw what it would be like to be courageous in that situation. I feel like I should do that now.”

“I hope it works out,” I said.

“Don’t worry,” said Ines. “The next week and a half is going to suck, but hopefully he doesn’t do anything stupid and then this all just goes away, like a bad dream.”

*

The more I gave to the internet, the better.

*

I didn’t know what I wanted, all I knew was how poorly I felt without it.

Romantically, I still felt like a five-year-old, one that confused fantasy with reality, was afraid of darkness, loud noises. I had spent my high school years being awkward and not handsome and thinking that love and sex and relationships would happen to me eventually, that all I had to do was to avoid thinking about it too much and just wait. Since then, I had had girlfriends and ambiguous relationships and other things, but those had weirdly bounced off of me like a kind of minor deflection. It seemed like I was still waiting and would continue waiting, quietly waiting, like I was in love with the waiting and would miss the waiting if I were to get into a relationship I felt anything other than indifference towards.

*

I had learned English, my second language, almost by accident, from television sitcoms and role-playing video games. For some reason, I seemed to enjoy speaking English more than I did French, even though in conversation my French accent came out from time to time, or I would search for a word or expression and couldn’t think of it and had to stall mid-sentence while trying to remember, which was anxiety-causing and felt like looking for a light switch in the dark, groping the walls at random, hoping to stumble onto the switch.

*

A meteor shaped like my head, colliding with my head.

*

On a billboard at work, someone had put up a small poster with company values on it. “Endurance,” read one of them. It felt like what they meant was, “How long can you endure being deprived of meaningful work?”

For a while, I had wanted video games to be a career for me, but then games changed or I changed or something changed, and I began to feel like what I was doing with my life was odd, unfulfilling. Moving to Montreal and starting a new job at a studio that mass-produced video games and employed about six hundred people had only accentuated this sensation. The office I worked in was overwhelmingly clean-looking, overly air-conditioned, many shades of grey, filled with desks that were shiny and curvilinear and looked like something out of an alien vessel. I didn’t know most of the employees occupying the desks around mine, wasn’t even sure what their jobs were. Like me, they didn’t talk much, clicked on things at a normal speed, looked focused but not stressed.

It was a lonely work environment.

On my work computer, I checked my email account and then Facebook account and then Twitter account. I thought about how those three actions had become synonymous with opening a computer. “We told Dan that he needed to be out by the end of the month,” read an email from Ines. “He didn’t want to at first. He yelled, ‘This kind of bullshit wouldn’t fly in Ontario.’ He said that less than two weeks of notice was illegal because he had been living with us for more than ten days, which I don’t think is a thing. At some point, he got tired of arguing and just gave up and said he would move out. Living with sketchy roommate is really awkward now. Thus comical. It’s passive-aggressive behaviour all day. He sits at home and makes messes and doesn’t clean them and dishes out sass instead.”

Later, I used Craigslist to email strangers with minivans offering their services as independent movers. I listened to music using noise-cancelling headphones, talked to no one except via email or internal chat messaging, toggled back and forth between work tasks and a browser tab with Facebook open in it.

“Were you offended when I tried speaking French to you the other day?” typed Shannon on Facebook Chat. “I worry about some things in my life.”

“Not really,” I typed. “I thought it was funny, you talking in French.”

“I can speak French for real, though,” typed Shannon. “Or at least better than that.”

“I am a terrible employee,” I typed. “Sometimes I think I can’t possibly care less but then it happens again. I care less than I was caring.”

“I know that feeling,” typed Shannon. “Two years ago I worked at Fabricland during the summer. It was so underwhelming that it was almost overwhelming.”

“In a meeting this morning, we talked about a pet game for smartphones by another company,” I typed. “You tap balloons and then you tap pets and then the pets are happy and then it gives you more things to tap. It’s a great success.”

“Really?” typed Shannon.

“I think so,” I typed. “They seem to be making a lot of money with it. When we brainstorm ideas here, there’s always someone that’s like, ‘What would make a lot of money?’ Then people say things like, ‘The key in the dungeon,’ or, ‘Blocks falling down.’ I always feel like saying, ‘Dying alone,’ just to see how people would react.”

“Why do you even work there?” typed Shannon.

“I don’t know,” I typed. “I started in games when I was twenty-one. In Quebec City, people had serious jobs. I wanted to fit in. I thought things like, ‘Put on hair products, it pleases people.’ I really liked video games as a kid and didn’t think I would outgrow them as an adult, but then I started being really unhappy and I blamed the unhappy on Quebec City and moved here. Not as many people have serious jobs here. Everyone’s a DJ or something. Some people are more than one DJ. I have been feeling really burned out lately. I don’t want a serious job anymore. I probably never even really wanted one.”

“You should just quit,” typed Shannon.

“I will,” I typed. “I mean, the cost of living here is so low that there doesn’t seem to be a point to it. Growing up, my parents were stressed about money. My dad yelled a lot. When I moved out, I think I thought that if you ran out of money, you automatically starved to death. Maybe that’s why I still haven’t quit. But since moving here, I’ve been seeing people running out of money or owing a lot of money, but not stressing or starving to death. It’s been eye-opening for me, I think. I am getting there.”

“My dad is a business guy,” typed Shannon. “It’s his entire personality. When I was home for Christmas, he lectured me about my romantic life. He said I was open for business but running that business to the ground. He even makes business metaphors.”

“My dad is angry inside,” I typed, “but he also likes Zen koans and movies about escapades in foreign countries and unflavoured chips.”

“Do you talk to your parents often?” typed Shannon.

“Not really,” I typed. “In October, I talked to my mom on the phone. It was awkward. I told her I couldn’t do video games anymore and wanted to reset my life and had started creative writing part-time, and she was like, what’s wrong with video games? And why did you apply to an English university? She thought video games was a party career and that I would be doing that forever, so that didn’t make sense to her at all. Then she said, ‘As long as you’re happy,’ and I said, ‘I wouldn’t call it that.’ ”

“They don’t miss you?” typed Shannon.

“I think they don’t really want to be parents anymore,” I typed. “They treat my sister the same way. They have more money now, so they buy expensive things and wait at home for the things to seem less interesting and then buy new things. They don’t have friends and never see anyone or do anything. I think they’re going feral, like wolf people. Soon they’ll eat the dog. You can go feral and still live with a certain level of comfort. My parents are proving that.”

“In high school, I did these talent shows,” typed Shannon, “but my dad didn’t want me to take singing lessons. He was afraid that all I would want to do after that was art. He was right.”

Celebrate the launch of New Tab at Librairie Drawn and Quarterly on Thursday, April 24!