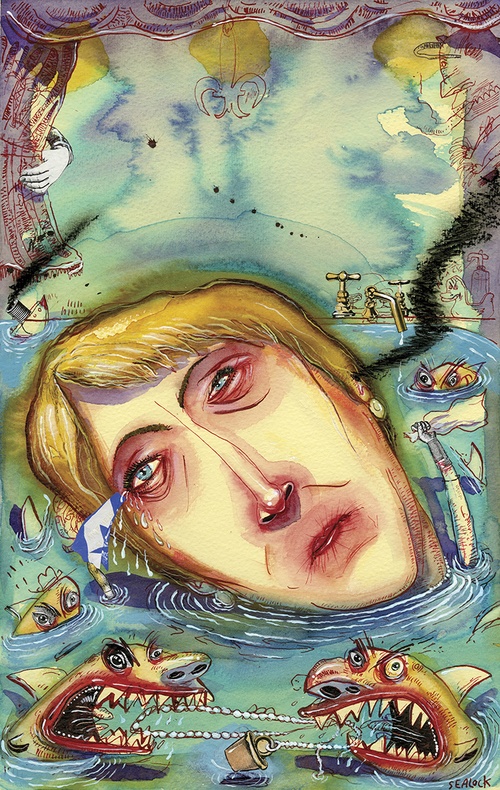

Illustration by Rick Sealock.

Illustration by Rick Sealock.

Parti Pooper

Nineteen months after Pauline Marois led the Parti Québécois to victory, she dragged it to defeat. How will history remember the province’s Iron Lady?

IT’S HARD TO BELIEVE that just a few months ago, political junkies in Quebec could barely get enough news. Beginning with the Parti Québécois’ (PQ) proposed charter of values, which sought to public servants from wearing religious symbols (turbans, headscarves, large crucifixes), followed by a snap election, the spring of 2014 offered public drama on a daily, sometimes hourly, basis.

National media treated the Quebec election as a curiosity happening on the margins, an embarrassing circus that would hopefully blow over and definitely never play Las Vegas, forcing news-hungry locals to channel-hop between Montreal stations and the two main francophone networks. Appropriate, since this particular spectacle was thoroughly en famille. It was so clearly a dénouement, and not a fresh crisis, that it hardly warranted—and certainly would not have benefited from—national or international intervention. By the time the last ragged candidate poster disappeared from the streets in May, the whole thing seemed like a mirage.

Except that the air was clear. After nearly twenty years of spin and grumble, Quebec voters were forced to face up to irreconcilable ideological tensions hidden for so long under personality politics and obscured by dissembling and delusion. This election confirmed important choices. Inadvertently—irresistibly—the PQ offered voters what was arguably the strongest call to independence since the referendum of 1995. The answer was resoundingly, polyphonically, negative.

Understandable. The majority—at least in the short term—has more to lose than gain from change. The masses prefer the status quo until it bites them individually. Change is the province of visionaries, and there are no visionaries on our political horizon. Technocrats, careerists, ideologues, well-meaning public servants: plenty. Which is why this chapter in Quebec history felt like the end of an era. The dregs of a withered vision went down the drain.

NAMED LEADER of the Parti Québécois on her third try, Pauline Marois became the first woman premier of Quebec in 2012, breaking a nine-year Liberal run with a PQ minority. Nineteen months later, the PQ suffered the worst electoral debacle in its forty-plus-year existence, becoming the shortest government in the National Assembly’s history.

There was no pressing reason for Marois to call an election, except that the PQ was ahead in the polls and she thought she could win a majority. No budget going down in flames. No risk that the controversial charter of values would fail to pass the National Assembly. None of Marois’ three opponents wanted or needed a spring campaign.

She was itching for one. In the heat of battle, she drove at high speed with one hand on the wheel, drinking coffee, eating a doughnut, whistling, tapping a foot. A fountain of confidence and certainty, she buzzed around the province dressed in steely business suits, stilettos and serious glasses, repeating a few pat policy lines over and over, face frozen in a glazed Stalinist grin. The two televised debates were breathtaking, exhausting. After thirty-six years in politics, including several important cabinet posts, her grip on issues was formidable. Her chief opponent, Liberal leader Philippe Couillard, emerged as a fiercely articulate policy wonk.

At Marois’ side, star candidate Pierre Karl Péladeau (PKP), wealthy scion of Quebecor, a conglomerate controlling a large percentage of the province’s media. In front of cameras, he punched the air like a well-toned Che, declaring indépendance as his reason for jumping into politics, changing the direction of the campaign. Suddenly, it seemed like the PQ was gunning for a majority solely to re-open a debate that most—including many inside the party—thought was on hold.

Couillard responded by taking on a major taboo. Declaring that there wasn’t a parent in Quebec who didn’t hope their child would be bilingual, he rejected the PQ’s claim that knowing English would threaten French. Gasps from the media, but the gesture served him well. He was speaking over the heads of one generation, directly to the next.

Baited by a reporter’s off-hand question about plans post-separation, Marois mused that Quebecers needn’t fear losing the Rocky Mountains or Green Gables. Borders would be open, the loonie in circulation, the Bank of Canada still our bank. During a group scrum, TV cameras caught PKP nosing up to the mic to speak, then the premiere giving him the elbow, taking the question herself.

THE PQ MISREAD PUBLIC OPINION on the charter of values. With polls showing that a clear majority of francophones were in favour, including a majority of Montreal francophones, it was possible to conclude that, by affirming the principle of a secular state, the charter spoke to widely-held values linked to the bad old days when the Church ran Quebec society: a motherhood issue.

It was. But one that, like abortion, generates passion and is largely impervious to compromise. It does not belong—or hold up—in an election, cannot compete with breadwinner issues like jobs, education, medical service, taxes, even personal and family ambition.

Nevertheless, the public debate that formed around the charter was important. It will have lasting consequences. It may turn out to be more significant than the election itself.

The charter acted as a lightning rod for many unexpressed indignities. Being angry, appalled, ashamed, scornful and derisive was a source of personal integrity. Such a great joy, to be mad at something Québécois without feeling reluctant or nervous about speaking up.

Once rolling, the debate over the charter allowed Quebec’s English-speaking chatting class to realize how long it’s been since we let ourselves get furious, openly, publicly. And many francophone opinion leaders joined in the debate which, for once, did not revolve around the question of independence.

BY THE SECOND ROUND of election debates, Marois was on the defensive, disaster in the air. François Legault, two-time PQ cabinet minister who left the party to form the right-of-centre Coalition Avenir Québec in 2011, and Françoise David, co-chair of the left-wing pro-sovereignty Québec Solidaire, were poised to siphon off feminist, socialist, urban, rural and business votes. A ludicrous situation, when you step back: a premiere who had dedicated her life to the causes of social justice and a sovereign Quebec, battling two foes with serious stakes in both causes.

The vote on April 7 produced a Liberal majority, decimating the PQ. Marois lost her own seat.

A shock, but maybe it shouldn’t have been. The Parti Québécois is, was—as political scientist Vincent Lemieux wrote as early as 1986—a generational movement. It began losing ground in the mid-eighties, when René Lévesque called for le beau risque—give federalism a chance. Public opinion polls since the election show that support for the PQ is weakest among young people. According to La Presse, the PQ’s 35 percent power base lies with francophones fifty-five and older.

On the night of the election, Pauline Marois was remarkably—some thought, shamelessly—upbeat. Her three acolytes, PKP, Bernard (Values Charter) Drainville and Jean-François Lisée had to come onstage first and face disappointed supporters. At her goodbye speech nine days later, Marois cried. She quoted French diva Edith Piaf: Non, je ne regrette rien. She still believes in a sovereign Quebec, and is sure it will happen someday. A fitting farewell from a legend in the making.

How will history treat Pauline Marois? Surely not as a failed politician, but as a principled representative of her generation’s project. While the campaign appeared disjointed, its basic elements had been in the debate—and in her career—all along.

Marois was and is true to herself, her cohort. Which is never, in the long run, anything but honourable. She is Quebec’s Boudicca, the Celtic warrior queen who raised an army against a foreign occupation, led tens of thousands to their deaths and came close to forcing a Roman retreat from Britain.

Centuries later, Queen Victoria was a Boudicca fan. The long arc of history has a way of transforming defeat into tragedy and tragedy into potent beauty. Especially with a player who has what it takes to smile through tears, and sing about la vie en rose.