All the Beautiful Girls

Sylvie Rancourt’s memoir from her time as a stripper was censored and seized when it came out in the 1980s. Shannon Tien on a long-deserved English translation of Melody: Story of a Nude Dancer.

MELODY IS NAKED, dancing onstage and waving around a crude handmade puppet with curly hair and an erect penis (technically, her finger). All eyes in the strip club are on her, but no one knows what to make of this beautiful dancer with a lust-filled doll. Some customers laugh (hesitantly), while others look on with dead expressions. None are aroused. The other dancers have a similar reaction. “Is she making fun of us or the customers?” asks one. “I don’t know,” replies another. “Well, she sure has balls.” Melody, meanwhile, is having the time of her life. I think they liked it. She walks off stage and moments later, club management forbids her from performing as puppet-master ever again. Her creation is confiscated.

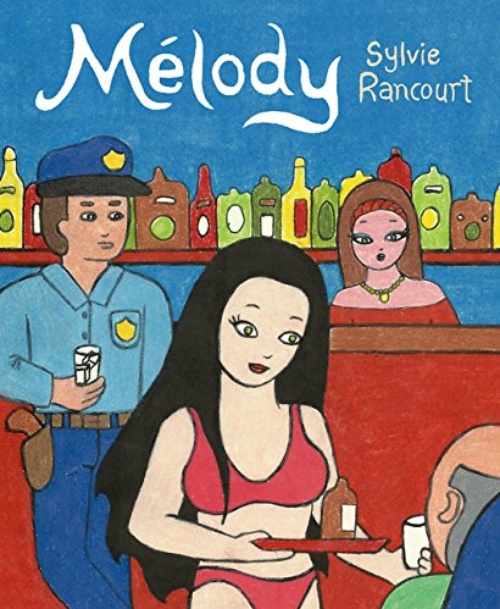

Melody is the alter ego of Quebec cartoonist and exotic dancer Sylvie Rancourt and the star of Melody: Story of a Nude Dancer. The collection—translated into English for the first time—documents Rancourt’s experiences as a Montreal stripper in the early 1980s, placing the work at the nexus of autobiography, sexual treatise and dark comedy.

The titular character’s puppet performance is a synecdoche for the entire seven-chapter book—and for Rancourt’s career as a comics artist. To say that Rancourt’s comics have received mixed reviews from audiences would be an understatement, but much like Melody after her dance, no one doubted that she was brave.

MELODY’S FIRST THREE CHAPTERS debuted in 1985 as a black-and-white photocopied zine. Rancourt had been dancing for four years and much of the public still perceived comics as petty art devoted to superhero fantasies, juvenilia or smut for niche audiences (Art Spiegelman’s Maus, now highly acclaimed for showing that comics could tackle serious subject matter such as the Holocaust, would be published one year later). Though the term “oversharing” had yet to be invented, the genre of autobiography was still loosely attached to the concept of confession. (Justin Green’s 1972 Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary—the first autobiographical comic penned in English—takes the form of a sacramental confession.)

Like Saint Augustine, author of the religious text Confessions, autobiographical subjects were often expected to seek redemption for their actions— the implied motivation of and reward for the act of confessing. It is not hard to see how readers, even contemporary ones, might expect the same from Rancourt, assuming the work would follow the “lost young stripper who eventually finds her way” narrative.

But Melody is not Magic Mike, the 2012 film detailing the adventures of a young male stripper (played by Channing Tatum) who learns the errors of his ways and settles down with a good-hearted woman. Melody is conspicuously unapologetic for her career choices; redemption is not a part of her game plan. We see her go from nervous, well-meaning amateur whose dancing plans are short-term and based out of financial necessity, to a confident pro who takes pride in—and maybe even likes—her work. When a client offers to hire her for his upcoming theatre production, she is surprised: “Oh ... Uh ... Sorry, but I’d rather dance.” When her boyfriend finds a job as a building superintendent, she continues her profession even though money is no longer tight.

In her ambivalence towards salvation, Rancourt recalls two other Quebec autobiographers writing in the nineties and two thousands: comics artist Julie Doucet and novelist/sex worker Nelly Arcan. Both wrote unapologetic “confessions” which, combined, tackle a range of issues that fall under the wide heading of conditions of female debasement: prostitution, miscarriage, masturbation, rape, the loss of virginity and sexual fantasies. Though Arcan’s work is undoubtedly angrier and more serious than Doucet’s and Rancourt’s, each reacts against the idea of a woman coming clean. It is hard not to link this reaction to Quebec’s own complicated relationship with Catholicism, the tradition that birthed the concept of confessional autobiography. By the time these women were writing, Quebec’s revolution against religious oppression was well underway. It is not surprising that Melody repeats her favourite curse when dancing for the first time: “Oh Lord!”

IN THE EPISTOLARY NOVEL I Love Dick, American writer and philosopher Chris Kraus questions our collective disapproval of women who speak frankly about their sexual experiences, especially when those experiences are ugly: “Why does everybody think that women are debasing themselves when we expose the conditions of our own debasement? Why do women always have to come clean?”

Kraus’ inquiry echoes softly in the innocently drawn pages of Melody, which themselves were the subject of frequent indignation and censorship due to depictions of naked cartoon women dancing and having sex with men. “I respect you as a person and acknowledge the duties of your work. However I see no utility whatsoever in your turning it into a pornographic publication,” wrote Solange Harvey in a 1986 edition of Le Journal de Montréal. “That’s unfortunate for you. Don’t count on any free publicity. You’ve fallen into mediocrity and facility.”

Melody was often sold as erotica in comic book stores, tucked away in back rooms. But out of sight was not out of mind for the government. In the early 1990s, the owner of Toronto comic shop Planet Earth was charged with “possession and sale of obscene material” because of the comic. The store was shuttered. Around the same time, the Toronto Police Service’s morality squad was raiding other comic stores across the city, and Melody was among the many magazines seized. Yet it’s hard to see how Rancourt’s drawings, famously amateurish and hardly sexy, could alone be responsible for such vitriolic criticism. Rather, what people found most outrageous about Melody was Rancourt’s refusal to ask for forgiveness.

Criticism of Rancourt wasn’t unanimous. Readers south of the border—where adult comics were more widely accepted—were more welcoming; the work even received praise from the likes of Aline Kominsky-Crumb, underground comics artist and wife of the legendary artist Robert Crumb.

Ten years into Melody’s run, Rancourt and Jacques Boivin ended the comic. The final chapter depicts Melody leaving the low-class strip club where she had been working, saying, “This is the end for me!” waving and smiling sweetly at the reader. It’s not clear whether she’s leaving the profession or simply the club, but it is clear that she’s not sorry about any of it.

THE CHALLENGE OF READING autobiography, even in comic form, is to maintain the division between the author and the author’s depiction of herself. While Rancourt does not draw herself as the victim of a relentlessly patriarchal society, neither does she present herself as the heroine of her own story. In a genre whose subjects are often treated either hypercritically or not critically enough, Rancourt is aggressively neutral in her rendering of Melody. There’s no question that the character is likeable, but she’s equally unsatisfactory as a feminist role model. She continues to sleep with her loser husband even though he gambles away all their money. She calls other strippers sluts and comments on their looks. She cheats. But Rancourt doesn’t tell us how to interpret these actions; her only interjections as narrator are to state the setting at the start of each chapter, repeating the lines “This isn’t the beginning and it’s not the end, but somewhere in the middle ... ”

It is a refreshing perspective for sexual memoir, which often suffers from heavy-handedness. Melody could not be more different from Chester Brown’s graphic memoir Paying For It. That story depicts the author’s experiences as a john, but focuses on Brown’s interjections, footnotes and lengthy argument for the legalization of prostitution more than the story itself. Like Rancourt, Brown does not ask his readers for forgiveness. But then again, Paying For It was never set up to be a confession in the first place because male heterosexuality is not something for which society demands apology.

Rancourt, playing as puppet-master of Melody, does not impose an infallible moral authority on readers; she trusts them to make their own judgments, or rather, not make any judgment at all. The act of confession is enough; it reaches beyond the action and makes an argument that women’s bodies, even when objectified, debased and sexualized, are not synonymous with shame, guilt or sorrow. Melody shows that women’s bodies can be funny, empowering, honest, and ultimately, not yours to define.

What does it mean that Drawn & Quarterly, the comics publisher most closely aligned with autobiography, is publishing the English translation of Melody on its thirtieth birthday? It is an apology of sorts, an amends for Canada’s initial coldness and censorship of Rancourt. It is a translation of words, but also of one female’s experience of physical objectification into a larger, more universal experience of female objectification. It is a stamp of approval, one that Melody the character would never have sought out—and would feel ambivalent about receiving, however deserved it may be. Ultimately, it is an act of defiance to package Melody between hardcovers in bookstores around the world when, a few short years ago, so many placed its photocopied sheets out of sight, out of mind.