Photograph by Chiara Soban.

Photograph by Chiara Soban.

At Least the Bombs Aren't Falling

Twenty years after the end of the war, Vesna Plazacic finds a hopelessness gripping Bosnia’s youth.

The basketball flies through the air and, for half a second, everyone stops to watch. It grazes the net, falling directly into the hands of an opposing team member. The shooter lets out a loud groan and rushes back to the other side of the court, wildly grabbing at another player’s shirt on the way, hoping to steal the ball again. Hoping to score. Hoping for a win.

It’s one of those exceptionally humid July days where rain threatens to plummet from the sky at any moment. Sitting on a patch of grass, I am chain smoking cheap Marlboros and watching the aggressive pick-up game unfold in my hometown of Tuzla, Bosnia.

My older cousin Jasmin is on the court, hustling in an over-sized Canada t-shirt that my mom brought on her last visit here. Jasmin shoots looks my way throughout the game, flashing the goofy smile I remember from childhood. That smile makes me feel at home.

In 1992, Jasmin and I spent weeks camping out in his building’s bomb shelter. I left Bosnia that spring, after the tanks started rolling in. My mother, older brother and I fled to Croatia. My father stayed behind to keep an eye on our house and the pub my family owned, thinking that the whole thing would blow over in a few weeks, a couple of months at most. The borders closed the day after our departure. He was stuck there for another two years. I was a child then but it was heartbreaking leaving everyone behind, especially Jasmin. As kids, we would build tents using blankets and chairs, and camp out. Even though I was the youngest and often the only girl among the mischievous boys, Jasmin was always kind to me, making me feel like I was a part of their secret club. After I left, I was discovering the beautiful beaches on the safe shores of the Adriatic while he was trying to survive without electricity, food or water. He and the rest of my cousins, aunts, uncles and grandparents were in a war zone under daily shelling.

Jasmin and I lived different lives during the war, and we have lived different lives since. But no matter the distance between us, whenever we reunite it is as if time never moved forward. We go back to our old jokes. We go back to our teasing.

When Jasmin finally gets a break from the basketball game, he drops on the grass beside me and points out some of the players. That group over there are the English teachers. And over by the net is a German professor. There are doctors, there are medics, economists, lawyers and veterinarians. Jasmin himself is a sports professor. They are all between the ages of twenty-five and forty-five, with PhDs, years of education. And many of them are under-employed—victims of a wrecked economy. The same group of players meets at this court week after week to push and shove and swear and scream and sweat. The game acts as an outlet. It has been twenty-three years since I left the Bosnian War behind and twenty years exactly since the conflict officially stopped, but in many ways the war here has never ended.

From the outside, it seems as though there is not much for young people in Bosnia to look forward to. Those between fifteen and twenty-nine represent about a quarter of the country’s 3.9 million person population.

And these youth have an unemployment rate hovering around 60 percent. Bosnia’s rate of unemployment is among the highest in the world; half a million people here are without work.

Some, such as Jasmin, find occasional jobs, a series of monthly contracts that they cycle through. There are no benefits and they can be fired at a moment’s notice. The pay amounts to about 850 convertible marks a month, that’s $600 Canadian dollars. It’s enough for Jasmin to buy food and the occasional drink with friends, but not enough to plan a future. Others must turn to jobs in the so-called grey economy—informal work that includes everything from fixing computers to selling wares online and street vending. It has become the norm. “A number of people have money to, so to speak, push through to the end of the month,” Jasmin says. “The second part is reduced to survival, where people simply do not have enough money to survive for several days.”

Rajko Tomaš is a professor of economics at the University of Banja Luka and an expert in the country’s informal sector. He says that yearly grey economy salaries, which are largely off the books, total some 1.3 billion euros. If these jobs were taxed they could provide the state with an additional 970 million euros in revenue. This could make a big difference to a government starved for funds. Tomaš says that while the economic situation has improved since the war, it’s still not good. The foundational development that has occurred over the past twenty years has been slow, with progress made through international loans, leaving the country drowning in debt. But not everyone is struggling. Jasmin mentions the politicians, the criminals (he says the two are often linked) and the war profiteers who have amassed an enormous amount of wealth, living in massive homes and driving flashy cars. They are photographed enjoying expensive vacations while the masses struggle to get through the week.

Some of my first memories of childhood are of sitting between my giggling parents on the couch, pretending to understand the dark humour of Top Lista Nadrealista (The Surrealists’ Top Chart). The show aired from 1984 to 1991 before the comedy group's eventual breakup due to political differences—not uncommon in Yugoslavia. But in their prime, in the days before the electricity was shut off in most cities, they attempted to lighten the mood with their political sketches.

Satire has been a part of Bosnia since the start of the warring years. When the bombs started falling in Tuzla, Sarajevo and surrounding cities in 1991, the Surrealists created a satirical sketch, about ethnic divides and the lack of food and water, which eventually became the grim reality.

The attitude perfected by the Surrealists survived the death and carnage of the nineties. Decades later, I can still hear its echoes in not only my family’s vernacular, but also the country’s. You can hear it in the streets: in the way that people greet each other, in casual conversations. Even now, Bosnians like to joke about how great it will be when they finally get a pay cheque someday. The young people here do what they learned from their parents: make the best of any situation, laugh it off and be thankful that the bombs are not dropping.

But this blasé attitude adds to the larger problem in Bosnia. “Unfortunately the vast majority of young people have become so passive that they do not have the will to collectively fight for a better life and better coexistence,” my cousin says. “It’s become an individual struggle and fight for yourself and your goals, according to the principle of ‘You give me what’s mine, and for the rest I do not care.’”

Like me, Jasmin Mujanović fled Bosnia in 1992. Today he is a political science PhD candidate at York University in Toronto, specializing in Balkan studies. He says that most Bosnians do not think that influencing the political process is their role—that it is someone else’s responsibility.

Damir Arsenijević battles this kind of attitude on a daily basis. As an associate professor of English literature at the University of Tuzla, he sees young people becoming more and more passive about their futures in the country. It’s heartbreaking to see generation after generation of young people growing up in Bosnia dreaming of leaving, he says. A 2013 World Bank report confirms that the country’s youth are fleeing to Western Europe and the United States. It is a great migration to greener economies. They don’t think they can change the status quo at home.

This political apathy is something that Arsenijević attributes to the war; there is a structural shame around resistance, around wanting change or desiring anything more than the peace that currently exists. “[People think] ‘Well we survived, at least the bombs aren’t falling, there are people worse off than me.’ You’re being bribed into acquiescing, and I think that’s the insidious work of politics of the elites,” he says. “Any sort of resistance is then seen as a sort of aberration.”

In his work with youth, Arsenijević tries to provide venues for them to participate in open discourse about politics, to have a space to create and produce, to expand their imaginations. This is done through reading poetry together and talking about the war. And he remains hopeful that change is on the horizon, that these feelings of frustration can be used for growth. “You have people who want to do something. And they know that in order to do something they just have to get up and do it without any guarantees. I think there’s been this sense of liberation in that. There are really no guarantees. There is really nobody to count on but yourself,” he says. “It’s so beautiful to be in Bosnia now ... You can actually have an impact, even through small-scale actions. You can do something collectively.”

The debut of the 2013 Tuzla-made documentary film Glas Dite (The Voice of Dita) is an example of the kind of small-scale action Arsenijević references. In 2012, well before the protests shook the country, the filmmakers of Glas Dite began to document the personal stories of unemployed factory workers in Tuzla and the budding frustrations of citizens towards their politicians. With the launch of the small indie film in 2013, the conversations began in the streets.

In February 2014, Arsenijević was walking through the streets of Tuzla past burning structures. Pillars of smoke reached the sky. Hundreds of people had gathered in front of the cantonal—or regional—government building, surrounded by a wall of police. Arsenijević had seen the same buildings burn in the 1990s. Back then, he had ducked into bomb shelters with the other children and waited for death to pass. But this time he was not hiding. It was not war breaking out around him. It was revolt.

Following the war, those who came into power took ownership of the country’s resources into their own hands. Because they had money and were politically powerful, they created their own laws.

With nearly no legal consequences for their actions or any legitimate processes in place to prevent risky business transactions, the privatization of most aspects of production began. In Tuzla, the industrial heart of the country, it was the furniture and washing-powder companies, such as Dita, that employed most of the city’s population. These were once considered safe and lucrative jobs under state ownership. The workers were decently paid and could rely on a pension after their years of service.

Once these companies were under privatized ownership, the contracts obliged the new parties to invest in their businesses to make them profitable. Instead, the owners sold the assets, stopped paying workers and, by the early 2000s, filed for bankruptcy. The four major industrial giants in Bosnia collapsed.

Workers were outraged, demanding that they either receive years of unpaid salaries or have their jobs back. The government refused to do anything, claiming to have no authority to interfere with private companies.

The massive gathering of disgruntled workers began in Tuzla—the third largest city in the country—and quickly spread, building momentum as it reached the capital, Sarajevo. Workers from the smaller surrounding cities joined the movement. It was dubbed the Bosnian Spring. Thousands were in the streets, aiming to overthrow what they said was a corrupt government.

A 2011 United Nations report shows that Bosnians rank corruption as the fourth most important problem plaguing their country, after unemployment, government performance and low standards of living. Left with little choice, citizens often must pay bribes to gain access to services they desperately need. The report states than 15 percent of citizens in the last national election and 13 percent in the previous local elections were asked to vote for a person or party in exchange for money, goods or a favour.

The very people who were active in creating and fighting the Bosnian War are still in the highest positions of power in Bosnia and Herzegovina, says Jasmin Mujanović. “Despite tremendous intervention by the international community during and after the war, the fundamental political realities of Bosnia remain unchanged. It is an unaccountable political system, an oligarchic and quasi-authoritarian political system that is economically dispossessed.”

As the protests grew, so did the conflict. The building of the Bosnian Presidency in Sarajevo, where the state’s archives are stored, was set aflame. Over two months, across twenty towns and cities, tens of thousands took to the streets. About two hundred were injured in clashes with police. Officials across the country, including the government of Tuzla, resigned.

And then, nothing.

The Bosnian Spring lost momentum. The protesters left the streets and people began sweeping up the glass and the debris. It did not achieve all its goals. “It was an incredibly important first episode,” Arsenijević says. “But that’s all it was, it was just an episode.”

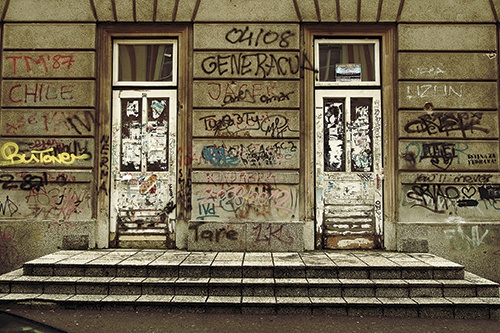

When I visited Tuzla in July 2014, Jasmin took me to see the scars from the aborted protests. I marvelled at a monstrous low-rise office building in the city centre with busted windows and blackened walls. There is no money to repair it, I am told, and no one is taking blame for the damages. So it stands there.

How does a nation begin to heal old wounds? It must pick at them. In April 2015, Arsenijević was watching Tuzla burn for a third time—this time at a screening of his documentary about the protests, Bosnia Rising. Sitting in a lecture hall at the University of Toronto, I watched the protests unfold alongside interviews with locals and disgruntled factory workers.

The planning sessions during the lead-up to the Bosnian Spring were, for many people, a first opportunity to speak of their experiences during the war, to share their trauma. Arsenijević says that while the protests died out, the much-needed conversation about healing began.

Bosnia needs to deal with the past to be able to grow, Arsenijević says. “You have people saying, ‘Oh let’s just stop talking about the war, we don’t want to talk about it, it’s over now,’ but the problem is it’s not over,” he says. “They want a clean slate and there is no such thing as a clean slate.”

Mujanović says that open communication across Bosnia’s many ethnic lines and religions and languages—divides that have outlasted the war—are needed to break down barriers and bring about change in a country that is marred by the past. “When the protests happened, one of the most constructive things that I thought we could do was to take the things that were being written in Bosnia, in the plenums, and to start translating them and to say, ‘No, these people are not insane, they’re not primitive, they’re not nationalists either,’” he says. “The same demands [of the government] that were coming out of Prijedor were coming out of Sarajevo, Tuzla, Trebinje; Serb, Bosniak, Roma, Croat, it didn’t matter.”

Despite their ethnic or religious differences, the protesters who took to the streets experienced the same kind of hunger, fear and isolation during the nineties as their peers. And it was their collective anger, frustration and sadness that brought them together again.

It is difficult to talk about trauma. Bosnians lost family members and friends to grenades and politics. They still have to walk the same streets that were once littered with bodies, blood and shrapnel. They must look at the blemishes from mortar shells on their apartment buildings. They can’t help but see the war day after day. But that doesn’t make talking about it any easier.

The first time I spoke with my parents about the war was four years ago, for a research project. I sat in their living room in Windsor, Ontario, taking notes. I listened to their stories. My father told me about a time he walked through a mine field in a forest, about the cigarette butts he recycled by candlelight, the anti-war protests he started, the endless hunger he felt, the massacres he saw in the markets, about his friends who were killed and those who betrayed him, his hatred of the army and about his darkest day, when he stood in the streets in Tuzla waiting for a grenade to hit so he would lose a limb and at least get a meal in the hospital.

My mother, who left her dream job teaching music in Bosnia, told me about the demeaning part-time service industry jobs she worked around the clock to put food on the table and keep us off welfare, the nights she sobbed alone, exhausted in bed, not knowing if my father was alive, if she would ever see him again, the crippling reality of death on every news channel and her struggle to never let us kids see how afraid she was.

During this conversation, I played the journalist. When I returned to my apartment in Toronto, I cried for a week. I wanted to talk to someone about the experience. I felt such immense love for my parents and guilt that I was too small to be able to help or understand any of it while it was happening. That feeling never really went away. I wonder how many other children from the war feel the same.

It can be depressing to talk about Bosnia. It has been the same stagnant story for nearly two decades: the economy, the politicians, the war profiteers. But I can't help but feel a strange love for my home city of Tuzla. When I am there, I feel at peace.

Like Arsenijević, I have hope that the young can be inspiredto do great things, no matter their circumstances. Bosnians can learn from their experiences with hate and turmoil, he says. They must balance two ideas: that an inhumane amount of destruction is possible, but also that they can be neighbours again. Or, at a minimum, unite in their collective struggle for a better future.

Those thoughts are echoed by Mujanović. He says that we rely too much on the idea that Bosnia is unique in its people’s long-standing suffering, unchangeable corruption and complicated politics. This needs to be challenged. “We’re not the only place that ever had a war, we’re not the only place that had a genocide, rape, sexual violence,” he says.

You can remember the past while still holding out hope for the future. The first time I returned to Bosnia was sixteen years after I had fled. I spent most of my time walking the streets with Jasmin late into the night, trying to remember the city as it existed when we were kids, what the marbles we used to share looked like and what games we played in the bomb shelter underneath his building.

Before the conflict, War was our favourite card game. Jasmin and I would sprawl out on the carpet in his family apartment, playing hand after hand as the adults chatted, drinking and laughing into the night. Lying there, listening to the soothing sounds of traffic and chatter and the clacking of heels that would seep through the cracked window from the bustling street below, Tuzla felt like paradise. Sitting on Jasmin’s couch today, drinking the city’s finest pilsner and seeing him light up with that goofy smile as we watch Sarajevan sketch comedy shows, it feels like home.