Photograph by Staton Winter.

Photograph by Staton Winter.

Picture Day

The West is inundated with images of refugees. But as Seila Rizvic explores, every wartime snapshot is also a family photo.

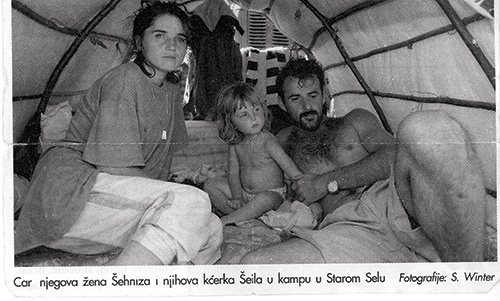

ONE OF MY EARLIEST family photos shows my father, mother and me together in a tent. There's a just-healed bullet wound visible on my father's leg. My mother looks tired; she had just spent the day waiting in line for medication. Then there’s me, two years old with a few chicken pox lingering across my chest and arms.

The picture was taken in the summer of 1994. Our copy was cut out from the local United Nations newspaper. We had just left our home, a village in northwest Bosnia—one small corner of the former Yugoslavia, which was torn apart by nationalistic wars in the 1990s. My parents kept the image long after our move to Canada. They even had it enlarged and framed before hanging it up on our living room wall. After passing by it day after day, though, the photo became familiar, blending into the background. Just another image in a world full of pictures.

Then last summer, while visiting my parents, I took a closer look at this family photo and noticed things that seemed unremarkable before: how the tent was too small to stand up in; how someone had abandoned a plastic doll in the background; how young and vulnerable my mom and dad looked at twenty-three and twenty-six, respectively. I also noticed a caption: “Meho Rizvic, his wife Sehniza, and their daughter Seila, in the camp at Staro Selo”—then, separated by a dash—“Photography by S. Winter.”

Curious to learn more about the photographer, I set out to find him online. After a brief search, I came across an email address for a photographer named Staton Winter. I sent a message with the image attached. Within a few hours, my inbox lit up with a reply: “Dear Seila, Wow. I am the one who took this photo.”

Stunned, I didn’t know what to think. I felt as though a wormhole had opened up in front of me, connecting the past and the present. Without realizing it, I had begun a long process of trying to understand the deeper meaning of a photo I took for granted for so many years.

Today, more than twenty years after my parents and I left Bosnia, there are still refugees in the world—hundreds of thousands of them, in fact. The current refugee crisis, fuelled by wars in Syria and across the Middle East, has been immortalized by photos of families just like mine: men, women and children sitting in bus stations waiting for food, trapped behind border fences and holing up in dilapidated refugee camps. Every day, countless times a day, photographers will walk up to a family and take their picture. This picture may then be posted on Facebook and printed in newspapers, or flashed across television screens. These images of suffering are used to prompt or prevent political action, to inspire pathos or anger, to inform and entertain. But these aren’t just documents of historical events, they are family photographs, each containing memories. I couldn’t help but wonder what other refugees see when they look at themselves staring back.

“FOR A LONG TIME some people believed that if the horror could be made vivid enough, most people would finally take in the outrageousness, the insanity of war," wrote Susan Sontage in Regarding the Pain of Others, her book on war photography. This belief, she eventually concluded, was misguided. Sontag cited Ernst Friedrich’s War Against War, “an excruciating photo-tour of four years of ruin, slaughter and degradation,” and Abel Gance’s 1938 anti-war film J’accuse, both of which explore the atrocities of the First World War. At the end of Gance’s film, his protagonist is surrounded by the bodies of zombie soldiers rising from a military graveyard. To the crowd of people around him, he screams, “Fill your eyes with this horror! It is the only thing that can stop you!” Despite this exhortation, despite the efforts of artists, filmmakers, writers and photographers of all kinds collectively imploring the public to face its horrible effects, as Sontag wrote, war returned the following year.

If images of suffering are not enough to stop us from recommitting the mistakes of the past, then what is the purpose of war photography? Much like the efforts of Friedrich and Gance, the contemporary war photographer memorializes the dead and warns the public. But they also serve another purpose: war photography today is meant to highlight the plight of still-living victims. Because of this, the relationship between photographer and subject becomes more complicated and more significant.

After my initial correspondence with Winter, which was overwhelmingly positive, I reached out to some other war photographers to see how they viewed their relationship with their subjects. Sam Tarling, who has worked in Iraq and Syria, told me that for him, establishing a good photographer-subject relationship is all about respect. “If something amazing is happening I’ll take a picture of it because you have to catch the moment,” he said. “But I’m much happier when I’ve introduced myself first, then hang around for a bit and wait for people to forget I’m there.” Still, Tarling admitted that the camera can and does create a power dynamic where the photographer is in a position above the person they are photographing.

Amy Smyth, whose work photographing children in a Jordanian refugee camp recently appeared in the Guardian, has a similar perspective. “For me there has to be a connection between the photographer and the subject or it’s just another news photograph that hits my consciousness for a split second before dissolving into the abyss,” she said. “I want to hold people’s attention and that requires a much deeper connection with the people I photograph.”

“Connecting” to both subject and viewer was a common preoccupation for the photographers I spoke with. If the moment of connection was strong, then the limitations of the photograph could be transcended, a moment of humanity would occur and the photographer’s goal could be accomplished. But “humanity,” like “connection,” is an elusive idea. That we can be stunned into understanding a complex conflict through a snapshot seems idealistic or even naïve, and describing a photograph in terms of its ability to connect to the viewer and showcase humanity seems clichéd. One image cannot stand against the power of whole geopolitical systems or virulent nationalism. Human emotions are not so simple that we can be moved to action by just one small prod in the right direction.

And yet, my own experience has shown me that there is, sometimes, something true to the cliché. My family’s war photograph did manage to achieve a moment of transcendence, so much so that whenever my parents and I looked at it closely, we turned soft and misty-eyed.

Beyond my own experience, the photo of Alan Kurdi, the young Syrian boy who drowned with eleven others trying to reach Europe, provides another example of what we might self-consciously call “the power of the image.” Last year, Kurdi’s photo became a turning point in the West’s perception of the refugee crisis in Europe. The photo went viral, along with the hashtag “#humanitywashedashore,” precipitating a palpable change in the way the media treated the refugee crisis. As journalist Susan Delacourt mentioned in a recent Canadaland interview, the image even helped mobilize Canadian voters to support the Liberal Party, which promised swift action on Syrian refugees if elected.

However, as shocking and heartbreaking as the image was, as much as viewers showed sympathy for the plight of Alan Kurdi and his family, refugees wishing to enter Europe, Canada and America continue to face relentless obstacles, including border fences, quota systems and a general climate of xenophobia made worse by the rising far-right. Considering all this, we might be tempted to conclude that the image of Alan Kurdi—the heart-wrenching image of any refugee attempting to find safety far from home—is, in the end, inconsequential.

But we only reach this conclusion if we conceive of war photography as a means to an end, a tool whose value is measured by its utility. Sontag invites us to look at war photography as an art. Like any art form, it is difficult to predict the impact it will have on its viewer. But this doesn’t diminish its importance. War photography moves us in many, sometimes conflicting, ways, but its primary role is simply to allow the public to come and see for themselves. If we choose to look away, to ignore what we see, then perhaps the problem isn’t in war photography itself—it’s with us.

AFTER I CONTACTED STATON WINTER, I became newly fascinated with the family photo I had known for nearly my whole life. The photo marked a point in history, one that revealed the culmination of everything that had come before it, but nothing of what lay ahead. I was eager to tell Winter, and he was eager to know, what my family had accomplished since leaving the refugee camp. “It makes me so happy to hear that your family is well,” he wrote in one of his emails, “and you have all made something positive out of your lives.”

When I asked other photographers if they had ever been contacted by the subjects of their photos, their responses were wistful. Smyth thanked me for reminding her that she needed to send prints to some of her subjects; she also said she hoped to return to the Jordanian refugee camp she’d visited in the summer of 2015. “I’m not a photojournalist who goes in, comes out and never looks back,” she said. But sometimes logistics get in the way of maintaining contact—keeping in touch with someone you meet fleetingly is hard enough, and much harder when one or both parties is in the middle of a war zone.

Tarling made a different point: perhaps it is the subjects who do not wish to maintain any kind of relationship after the moment of the photograph has passed. “At the end of the day,” he said, “there’s just a person on either end of the lens, and the same rules, social constructs, expectations and such that exist when any two strangers meet apply here just as much as anywhere else.” Maybe, he continued, wriggling his way into someone’s life just because he’d taken their photograph would be an act of narcissism more than friendship.

Tarling asserted that there was no “real great mystery” or “special situation” arising between photographers and their subjects—“just life happening as it does everywhere.” What, then, could explain my fascination with the photo Winter had captured? I turned to Sontag again. In discussing the trend of museums dedicated to preserving the memories of war, she noted that photographs do more than remind us of death and victimization. Rather, she wrote, “they invoke the miracle of survival.” Taking and preserving photographs is an act of faith— what Sontag identified as a commitment to renewing and creating memories. The photograph of my family in a refugee camp fulfills this promise on a smaller scale.

We looked to the photo, keeping it on our wall for so many years, because we wished to renew our memory. And yet, after years of seeing the photograph on my family’s living room wall, one day, without much fuss, my mother took the picture down and placed it in a closet.

When I called to ask what made her decide to put the photo away, my mother seemed thoughtful for a moment and then joked that she didn’t like the frame it was in (thin and plastic and painted a brassy gold). After I pushed her for a serious answer, she sighed, sank a little and said that she just didn’t want to remember any longer.

I tried hard to reconcile my mother’s desire not to remember with everything I had read and learned on the subject of photography, on the human desire to remember, to bear witness and to always be in a process of looking back on their past. Wasn’t she at all interested in “invoking the miracle of survival,” as Sontag suggested?

After considering her position for a while, I realized it made sense: memories can be painful and looking back may not always be a positive experience. More recently, I was reading the work of the poet Anna Akhmatova, the “keening muse.” In a poem titled “Lot’s Wife,” she writes about the titular character who turns back one last time to look at the city of Sodom as fire and brimstone rain down upon it, only to be turned into a pillar of salt. Akhmatova’s poem reminded me that looking back can sometimes feel as dangerous as forgetting. My mother and I both appear in our photo, but I have no memory of the refugee camp or the day the photo was taken. She does. While I look to the photo to understand my past, my mother only wants to move forward.