Illustration by Brandon Celi.

Illustration by Brandon Celi.

Hook, Line and Screecher

As Brad Dunne explores, there are three ways to become a Newfoundlander: by birth, by residence or by initiation.

IT’S A FRIDAY NIGHT at Christian’s Pub in downtown St. John’s, Newfoundland. The bar is packed for a February. As 11 pm approaches, the crowd is eagerly waiting for Keith Vokey to arrive and perform his famous Screech-In ceremony. The tiny top floor—reserved for Screechers and their guests—fills quickly. The space heats up as everyone orders their pints, still bundled up in their winter coats because there are no more hooks left to hang them on. Rihanna’s “Work” plays on a jukebox in the corner. The tables and chairs have been pushed against the walls to create space in the middle of the room, where about a dozen tourists wait attentively in groups of threes and fours, their friends watching from the sidelines.

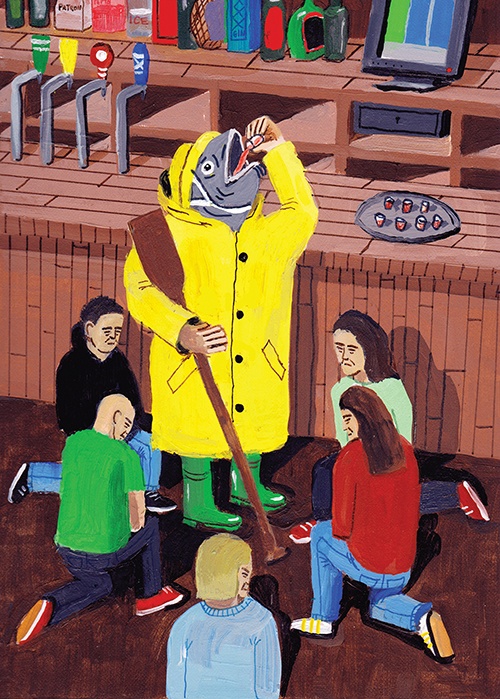

Fifteen minutes later, Vokey, dressed in green oilskins, bursts out from a door at the back of the bar, clapping his hand against a wooden oar. His long, curly hair has been tied into a ponytail and tucked into a green fisherman’s hat called a sou’wester, which is proportioned like a mullet—short in the front, long in the back. Small droplets of sweat are already beading in his salt-and-pepper beard. After the jukebox has been turned off, Vokey opens the night with the first verse of the “The Islander” by local favourites Shanneyganock. “I’m a Newfoundlander born and bred and I’ll be one ’til I die,” he sings. “I’m proud to be an islander and here’s the reason why; I’m free as the winds and the waves that wash the sand; there’s no place I’d rather be than here in Newfoundland.” Vokey is a capable singer in his own right—he’s played in a few groups, including a tribute band called The Beach B’ys—but his performance tonight is mostly about volume and theatrics.

“I sees we got some come-from-aways here,” Vokey says when he’s done singing. The inductees look to each other, bemused. “Who are ye and where do ye come from?” he asks, laying his accent on thick. A blonde, college-age woman responds sheepishly. “My name is Jennifer,” she says, “and I’m from Ontario.” Vokey teases her by mimicking her timid mainland accent. “I’m Dave,” another asserts more confidently. “I’m from Alberta, but my parents are from Newfoundland!” (Many tourists testify to their local roots during Screech-Ins.) The rest of the group comes from New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island and Scotland, respectively. They form a sloppy circle around Vokey, nervous but smiling, like how you might imagine a group about to jump out of an airplane. The crowd laughs as Vokey gives each of them a hard time.

The first step of Vokey’s ceremony requires a contribution from the Screechers: everyone is expected to chip in with a song, a dance, a joke or a story. When Vokey asks Abbey, a young woman from New Brunswick, if she knows any songs, she surprises everyone with a verse from “I’se the B’y,” a traditional Newfoundland song made famous by Great Big Sea. Her voice is soft and quiet but full of liquid courage. Kieran from PEI dances a clumsy jig. The Scot tries to tell a joke, but his thick accent baffles everyone, even Vokey, who usually has an ear for dialects.

Next, Vokey asks the group, “Is ye Screechers?” The correct answer is “Deed I is, me ol’ coc’, and long may your big jib draw,” but the participants struggle. “Deed I am a big ol’ cock,” Abbey announces. Vokey coaches them through it. The audience laughs as the come-from-aways twist their tongues around the Screecher’s creed. By the end of the night, this ragtag group of strangers will be dubbed “honorary” Newfoundlanders. But first they’ll need to get through the rest of the ceremony, culminating in a shot of the island’s most infamous drink.

WHEN IT COMES TO SCREECH-INS, Christian’s Pub, which sits at the south end of the bustling George Street, is hardly the only game in town. George, as the locals call it, is the heart of St. John’s pulsing id. Though it only manages to cover two blocks, the so-called “biggest little street in the world” boasts the greatest number of bars per square inch in North America. At the north end is Trapper John’s, self-appointed “home of the Screech-In,” where owner Terry Gulliver estimates they perform approximately five thousand each year. In between Trapper John’s and Christian’s there’s O’Reilly’s, which does its own ceremony. Even a nearby strip club has reportedly gotten in on the Screech-In action. On the other side of Signal Hill is the Inn of Olde; and then, of course, there are the myriad amateurs who perform the local tradition at parties.

Despite the competition, Vokey is considered St. John’s unofficial Screecher laureate. The forty-five-year-old performs at Christian’s four to six times a week, depending on the season, and he’s also hired for private functions and conventions. While Vokey doesn’t keep exact records, he estimates he’s Screeched- In at least 60,000 people over the past fifteen years—including cast and crew members of Hockey Night in Canada, California punk rock legends NOFX, and even his own wife, whom he first met during one event at Christian’s.

The ceremony’s title comes from one of the island’s most popular liquors, a Demerara rum affectionately known as screech. Folklorist Patrick Byrne dates the roots of the name to the Second World War, when American and Canadian servicemen filled the island, suddenly accounting for 10 percent of its population. According to legend, or at least the Newfoundland and Labrador Liquor Corporation, an American serviceman howled when downing the spirit for the first time. When his fellow Yank asked what the noise was about, a Newfoundlander responded, “The screech? ’Tis the rum, me son.”

The modern Screech-In ritual as we know it today emerged two decades later, and it is credited to Keith Vokey’s father, Myrle. Playing off 1960s’ counterculture—think bed-ins and sit-ins—Myrle Vokey first performed his Screech-In for a talent night held during a two-week professional development program for teachers. To generate ideas for the ceremony, Myrle’s father— Keith’s grandfather—recounted hazing rituals that sailors had used to bestow honorary Newfoundlander status on outsiders. Drawing upon his encyclopaedic knowledge of the island’s music and storytelling, Myrle synthesized (and softened) his father’s initiation rituals for the teaching crowd.

At the same time that Myrle’s (then rum-free) performances were gaining notoriety, the Newfoundland and Labrador Liquor Corporation had begun to sell signed and dated certificates emblazoned with “The Royal Order of Screechers” to visitors, proclaiming to the world that its recipients had tried the local screech. In 1971, the Liquor Corporation approached Myrle about marrying the two ideas: a ritual bestowing Newfoundlander status, crowned by a shot of screech. Thus, the legend was born.

NEWFOUNDLAND IDENTITY POLITICS are complicated. Before Confederation, the island belonged to England, whose politicians once described it as “a great ship moored near the Grand Banks for the convenience of British fishermen.” Newfoundland only became a part of Canada in 1949, thanks to the slimmest of majorities in a referendum, and the union is still a controversial topic in the province to this day—some believe relinquishing control of the cod fishery to the federal government led to its collapse and the subsequent cod-fishing moratorium in 1992.

But the contentious relationship between Newfoundlanders and the rest of Canada started much earlier. Ever since 1840—when the Newfoundland Natives’ Society was created to uphold the interests of Newfoundlanders-by-birth—the island and its inhabitants began to accrue a reputation for being idiosyncratic. The colony was perceived by outsiders to be inhabited by a rabble of fishermen who managed to eke out a pitiful existence amid miserable circumstances. Travel writers from the late eighteenth to the early twentieth century were fixated on the island’s rough climate, the hardships of its seal and cod fisheries and its poor residents’ quaint habits. Even now, Newfoundlanders are often described much like the eponymous dog breed: hearty, waterproof and jolly.

With this cultural baggage in mind, certain members of Newfoundland’s intelligentsia argue that the ritual of the Screech-In further reinforces the “goofy Newfie” stereotype. Bestselling author Kevin Major describes the tradition as a “ceremonial embarrassment” that perpetuates “the caricature of the dim-witted-but-friendly, rubber-booted Newf.” Patrick Byrne denounces the practice as a demeaning “survival technique” locals use to ingratiate themselves with outsiders. Many Newfoundlanders claim the Screech-In is nothing more than a pseudo-tradition meant to hustle tourists, and when the holiday season picks up every June, anti-Screech-In screeds appear in blogs and newspaper op-eds.

Philip Hiscock, a folklore professor at the Memorial University of Newfoundland, takes a different perspective. He sees the Screech-In as one of a type: an initiation ceremony performed by a smaller culture to welcome members of the larger, hegemonic ones. These sorts of rituals often pop up in places where tourism is important: there’s the phony “inductions” into Santeria in Cuba, L’Ordre de Bon Temps in Nova Scotia and the White Hat Ceremony in Calgary, to name a few. Hiscock describes these rituals as a type of “cultural backslapping,” and “a way for non-experts to parade and be proud of their culture.” There is also a subtle power move: the visitor from the hegemonic culture must now submit to the rules of the smaller one.

Moreover, Screech-Ins can be playfully subversive. By pushing the Newfoundland caricature to its most absurd dimensions, Hiscock argues, the Screech-In actually destabilizes popular perceptions and rebalances power dynamics. “Screech-Ins use popular notions of Newfoundland culture that are at odds with reality, but that’s the fun of it,” he says. “It’s meant to play up that sense of difference.”

Indeed, when Vokey explodes out of the back room with his oilskins and stereotypical dialect, he is ludicrously out of place. Christian’s may be an Irish pub, but none of the patrons or staff look like they just came off a schooner; Newfoundland’s economy is now primarily driven by oil, and most of the remaining fishery jobs take place in plants where men and women in white smocks work on production lines. It’s impossible not to realize Vokey’s performative fabrication.

As for Vokey, he sees himself as the unofficial vicar of an important practice. “I take all these stereotypes and turn them on their heads,” he says.

AT THE CHRISTIAN’S PUB SCREECH-IN, after the singing, dancing and joking are done, samples of “prog”—tiny squares of bologna, referencing the fried slabs colloquially referred to as “Newfie steaks”— are passed around on a wooden cutting board for the participants to eat. Vokey then asks the Screechers to “get down on their knucks.” They gradually deduce what this means and one by one kneel down, seeming apprehensive of what could possibly come next. The bartender hands Vokey a small frozen cod, about the length of a child’s arm, from the freezer behind the bar. The crowd cheers as the participants each give the speckled brown fish a kiss on the lips.

Now comes the final showpiece: a shot of screech. “Be careful,” Vokey warns as it is being passed out. “There’s a reason why I wears the oilskins.” The audience claps and bangs on tables in anticipation. The Screechers wince as they down the rum in communion.

To cap off the ceremony, Vokey blesses each participant with his paddle as if conferring knighthood, and the Screech-In is complete. The mainlanders are given certificates acknowledging their newly minted status as honorary Newfoundlanders.

Now out of character, Vokey mingles with the crowd, chatting and posing for selfies. “Do me a favour now will ye?” he asks the group. “Wherever you may go from here on out, don’t be talking about no goofy Newfies.”