Illustrations and photographs by April Johnson.

Illustrations and photographs by April Johnson.

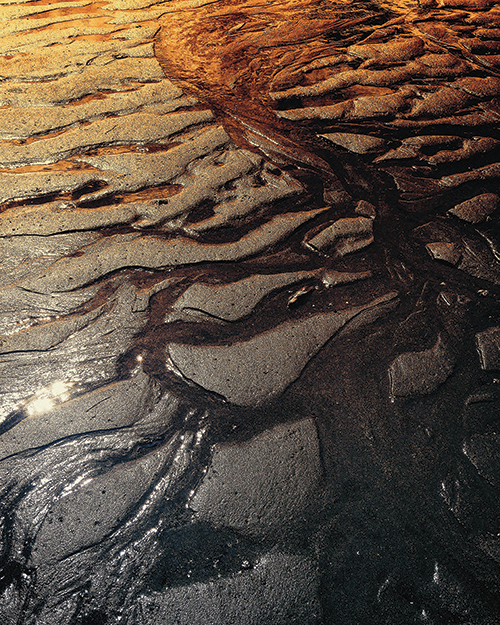

A River Runs Through It

The last time British Columbia’s Fraser River burst its banks, entire communities were submerged. With aging dikes and a growing population, Heather Ramsay reports, next time may be worse.

IMAGINE SEVERAL HUNDRED THOUSAND PEOPLE, living on some of Canada's most expensive real estate, trapped by cold, swirling water. Picture jets grounded at the low-lying Vancouver International Airport; visualize the TransCanada highway impassible in either direction; conjure three rail lines underwater. Phone and internet systems are down. Food supplies in local grocery stores are decimated within four days. Freight has difficulty getting in and out of the Port of Vancouver, causing nationwide economic disruptions. After all of that has sunk in, mix in sewage from several medium-to-large cities as well as 600,000 metric tonnes of floating cars, dead animals and other debris.

This could happen if British Columbia’s Fraser River, the tenth-longest river in the country, rises to levels last seen in the late 1800s, when the worst flood in the Lower Mainland’s recorded history deluged flat farmland and burgeoning riverside communities with water as far as the eye could see. The Fraser Basin Council (FBC), a non-profit organization concerned with flood management, predicts that with climate change and sea level rise, there’s a one in three chance this could happen in the next fifty years.

Most people think “ocean” when they think of Vancouver, forgetting about the broad river rolling by the city’s back door. But the Fraser—whose tributaries drain a third of the province—plays a key role in the city’s geography. At 1,375 kilometres long, its headwaters start in the Rockies, near the Alberta border, and rush northwest through mountain valleys, picking up volume all the way to Prince George. Just past the dry Chilcotin, the Fraser squeezes into a deeply incised canyon. Kilometres of white water later, including a contortion through a narrow passage called Hells Gate, the river finally widens at Hope. At this point, barely five metres above sea level, the mighty Fraser sweeps through 160 kilometres of flat, floodable cities such as Chilliwack and Port Coquitlam, before meeting up with Richmond and Vancouver at the river’s mouth.

The danger time on the Fraser is during the spring freshet, when meltwater from the winter snow races out of the mountains and down towards the sea. Most years the flow is manageable, but every once in a while the rushing river becomes unwieldy. A new report, released in May 2016 by the FBC, tallies the vulnerability that communities face in British Columbia’s otherwise idyllic but ever-growing Lower Mainland. Adding it all up, the FBC report predicts that when the Fraser breaches its banks, it can cause losses valued at $2.6 billion to private houses, $3.8 billion in commercial buildings, $880 million in public institutions, $4.6 billion in infrastructure and $1.6 billion in agricultural lands—approximately $13.5 billion in total.

“MOST PEOPLE NEVER BELIEVE how high the water will rise,” says natural hazards expert John Clague, a bookish-looking professor of Earth sciences at Simon Fraser University.

Seventeen-year-old Betty Mitchell didn’t. In spring of 1948, she lay fully clothed atop the bedcovers in her Abbotsford home, waiting for the coming flood. By 8 AM on May 31, the warning siren was wailing. The dike near Mitchell’s home lifted and crumbled under the pressure—up river near Hope, it was measured at 17,000 cubic metres per second, up from its average of 2,700—and an eight-foot wall of water burst through. Mitchell, who described her experience to historian K. Jane Watt in the 2006 book High Water: Living with the Fraser Floods, said her mother and younger brother fled while she and her father stayed behind to move the furniture up as high as they could.

There had been lots of warning. A few days before, according to Watt, the Langley High School graduating class was pulled from their prom to help shore up the dikes. The boys and girls were sent home to change out of their prom attire and report for sandbag and kitchen duty respectively.

Betty Mitchell spent the day preceding the flood making lunches for the volunteers working on the dikes. As she leaned over to hand her uncle a sandwich, he sunk into the spongy, water-logged soil constituting the only barricade between acres of farmland and the river—an indication of how precarious some of the berms were. “They hauled him up and he carried on,” Mitchell told Watt.

When the dikes broke, it was as if bombs had been detonated underneath them. Whole houses were spotted afloat. Described as the “monstrous child of quiet snow” in a newsreel later that year, the huge snow pack, cool spring temperatures and an abrupt shift to record heat—all the unique elements needed for a flood on a river the size of the Fraser—brought on the second-worst deluge in BC’s recent history. By the time all was said and done, five feet of water filled Mitchell’s one-storey family home. “We were putting things up a little higher, thinking we would be all right, but we weren’t,” she recounted.

News of the 1948 flood dominated the press for weeks. Many Vancouverites, cut off by floodwater but safe in their oceanfront homes, donated bags to fill with sand, took in the displaced and raised money to help those along the riverfront. Six weeks later, the water finally went back down. Eventually, memories of the flood receded. People either moved away, got older or passed on.

But a river never forgets. Ask local First Nations and you’ll find out that the Fraser Valley has always been known as a flood zone. The Stó:lō—the People of the River—describe at least one Biblical-style scenario in their oral history from countless generations ago. Stó:lō researcher Keith Carlson, in his 2010 book The Power of Place, the Problem of Time, quotes Old Pierre, an informant to anthropologist Diamond Jenness in 1936: “It rained and rained without ceasing until the rivers over owed their banks, the plains flooded and the people fled for shelter to the mountains where they anchored their canoes to the summits with long ropes of twisted cedar boughs.” Soon the storm knocked some of these canoes afloat and boats crowded with people washed away. Carlson explains that weather events such as floods have had huge impacts, and have even changed settlement patterns in the area. Because of the Great Flood, some Stó:lō, whose territory extends along the Fraser River, are said to have washed up in what is now northern Washington. Others floated away and settled near Bella Coola.

HUMANS HAVE ALWAYS LIVED BY RIVERS. John Clague points out that the deltas of the world—the Nile, the Euphrates, the Ganges—are heavily populated, because floodplains are at and easy to build on. They also provide ample water, rich soil for agriculture, and access to fish and waterfowl. “There is a reward to living on a floodplain,” Clague says. But like the Stó:lō, almost every culture has their own flood story, often connected to the wrath of an angry deity, and these narratives underline the dangers of water as a force.

Watt states that in the past, people better understood the risks of living by the river. Early settlers had “water consciousness.” “They were intimately involved with the Fraser and its tributaries,” she writes. “They considered flooding a natural event, part of the movement of seasons, and something they had to contend with in order to farm where they did.” When a flood occurred, neighbours helped each other evacuate; after the river went down, they’d get together to shovel out the sludge, rebuild and carry on. What would yesterday’s inhabitants of the Fraser Valley think, writes Watt, if they could peer forward to today?

The implications of flooding are more serious now than they were before, says Clague, because development is on the rise. In recent years, riverfront has become the new oceanfront in the Lower Mainland’s hot real estate market. Scores of homebuyers have ocked to areas once known more for sawmills and shipyards than luxury condos. Developments in Richmond, New Westminster and Fort Langley promise a blend of sunsets, bird watching and recreational opportunities, as well as glimpses of tugboats navigating the still-working river. But as the water laps gently along the banks, Neil Peters, retired inspector of dikes for the BC government and a longtime advocate for better flood management practices, thinks that buyers might be getting more than they bargained for.

“People don’t take things seriously unless they’ve seen it with their own eyes,” says Peters. He asserts that BC’s leaders should heed the warning provided by the 2013 floods in Alberta, where intense rain swelled a series of rivers in the southern part of the province, washing out sections of the TransCanada and flooding riverside neighbourhoods in Canmore, Calgary, High River and more. Five people died, including an elderly woman trapped in her ground floor apartment and four others who were swept away by the rushing waters. In some areas, the power was out for over a week, schools were closed and bus routes cancelled. The damage from the floods cost upwards of $5 billion to repair.

Alberta’s disaster underlines how devastating a flood can be to people and property. In BC, we know the flood is coming, says Peters, and we also know that the havoc will surpass anything the rains in Alberta wrought.

Peters’ biggest concerns are for Chilliwack and the just-above-sea-level-city of Richmond. In Chilliwack, more than 40,000 people’s homes, at least twenty schools, four fire halls, the Chilliwack General Hospital and the airport could be inundated if the river reaches 1894 levels. Peters is even more concerned for Richmond. Although the city has one of the best-funded dike systems in the region, Richmond is vulnerable to both the river and the sea. Rising sea levels due to climate change compound Peters’ fears, but there are other factors at play. In 2003, for example, a dike at neighbouring Queensborough, New Westminster, failed.

The potential disaster took place at a pump station and concrete structure known as a flood box. This key piece of flood protection infrastructure consists of a pipe with a control valve that cuts through the dike, forcing rainwater built up behind the barrier to flow away from houses and into the river. In the early morning hours of June 15, the professionally engineered dike around this culvert—inspected and approved by city officials just two days before—collapsed without warning. The river flooded in.

According to Peters, this happened during a time when the flow of the river was moderate. “If it happened when [the flow was high], in twenty-four to thirty-six hours Richmond would be flooded to the point that people couldn’t get out,” he says. Almost 200,000 individuals would have been affected.

There was minimal damage, thanks to quick action taken by municipal staff, but Peters points to a forensic analysis that found inadequate fill materials had been used. The soil inside the berm had been simply slipping away.

Queensborough, one of many hot new waterfront neighbourhoods, saw its population increase by 2,500 between 2001 and 2011 alone, thanks in part to municipally sanctioned efforts to refresh industrial lands. With so many moving onto the riverfront, Peters notes that this close call illustrates one of the most pressing issues identified in the FBC’s report—the state of the Lower Mainland’s 500 kilometres of dikes. At present, 96 percent of the assessed dikes do not meet provincial standards.

The last time a major flood hit the area, 2,000 homes washed away, and 16,000 of the area’s 50,000 residents were temporarily evacuated. Today, almost 325,000 people live in the same flood-prone lands. Altogether, counting Agassiz, Chilliwack, Abbotsford, Mission, Maple Ridge, Port Coquitlam, Pitt Meadows, Coquitlam, Surrey, Delta and Richmond, more than two million people could be affected by the coming flood.

In the years since the last major flood, property values have also ballooned. Take Richmond, for example: in 1948, you could buy a new house for under $10,000. In June 2016, the median price for a detached home was $1.7 million. Moreover, people don’t live in plank houses anymore. Simple construction methods, prevalent in the early part of the 20th century—wooden board walls, basic wiring—meant that houses filled with mud could, if worst came to worst, be cleaned out and lived in again. But today’s drywall, once wet, becomes a health hazard. Expensive appliances are toast. Wall-to-wall carpets turn into a soggy mess and complicated wiring for things such as basement movie theatres become their own horror show.

When the flood hit in 1948, a national disaster was declared. Thirty thousand civilians laboured to stabilize the dikes and help rescue some 25,000 animals. Three thousand army and navy personnel were assigned to the fight. Still, so much was destroyed. Today, the stakes are even higher.

THE LOWER MAINLAND EXPERIENCED the very worst the river had to offer in 1894. The Fraser crested at an incredible 7.9 metres, inundating the valley as far as the eye could see. At the time, few people lived in the area and the provincial government, barely up and running, had few funds to contribute to protecting flood- prone lands. According to Peters, the disaster led to a hodgepodge of makeshift dikes, but no region-wide plan. Fifty years went by with no floods and people became complacent. The dikes grew over with brambles and trees and, as Betty Mitchell and her family discovered, this compounded the impact of BC’s second-worst flood.

Officials got serious about dike management after that, says Peters. By July 1948, a three-person team called the Fraser Valley Dyking Board had been established, and they began ordering construction, repair and reconstruction of protective berms. Standards were implemented, money was spent, especially in the 1970s and ’80s, and people began to feel safe again.

In 2006, the FBC and provincial government took a fresh look at the Fraser River, incorporating staff’s understanding of the 1894 flood. Modellers realized that most of the barriers in place today would be overtopped—or in the worst-case scenario, fail completely—if that level of water came down again. Rigorous new standards demand seismic upgrade work as well as additional height on the vast majority of the valley’s flood protection infrastructure.

“You have to remember that when the river flooded in 1894, the water spread everywhere,” Peters says, explaining the height discrepancy. Chilliwack was awash from the Agassiz bridge to the United States border, a full fifty kilometres to the south. Parts of New Westminster, Pitt Meadows, Abbotsford and Langley were underwater, yet the river still reached the highest level on record. Dikes built on the river’s edge—protecting against overflow—have consequently narrowed the width of the river and cut off back channels that once reduced the main tributary flow. This means that during heavy flooding, Peters says, high water has nowhere else to go but over the top of the dikes.

Since most of the present-day dikes were built more than forty years ago, maintenance and design are also reoccurring issues. The FBC report rated 69 percent of dikes poor to fair and deemed 18 percent unacceptable. In short, what happened in Queensborough could happen again, soon, with greater consequences.

The FBC report also identified another significant gap in flood management protection: sixty First Nations reserves along the river are vulnerable. At Shxwhá:y, a village on the edge of the Fraser River near Chilliwack, community members got hold of any large earth moving machines they could to build a makeshift berm in 2007, when the waters rose to dangerous levels. It was touch-and-go for several days, with cold water lapping against sandbags and earth, but in the end the community was safe.

According to Shxwhá:y chief executive officer Murray Sam, the present-day village site was once a seasonal settlement area. Pre-contact, the Stó:lō peoples migrated with the seasons from up the Chilliwack River Valley to the mouth of the Fraser. But when the Indian Act was passed in 1876, that freedom to move was squashed. Now, the majority of Shxwhá:y’s 409 members live off-reserve. They got tired of packing stuff up every time the waters rose, Sam says.

As far back as 1894, local newspapers reported that the First Nations suffered worst from the floods, and this injustice is still felt today. “The government placed us on the water,” says Kwantlen elder Hazel Fallardeau-Gludo, whose family lived on McMillan Island, about fifty kilometres west of Shxwhá:y. In 1948, her family had huge gardens for vegetables and orchards of plums, pears and cherry trees. The family never bought supplies at the grocery store; everything they ate was grown, caught and preserved. They raised cattle and chickens. Even the ducks, says Fallardeau-Gludo, who was eight years old at the time of the flood, were plucked and sealed into jars.

When the floodwater came, her grandmother had to leave behind her crystal glasses and delicate blue and white china—the kind that Fallardeau-Gludo herself now shows visitors in her capacity as an interpreter at Fort Langley National Historic Site. Fallardeau-Gludo says that in 1948, Kwantlen community members were evacuated from their homes and brought to a farmer’s field in Langley. None of their non-First Nations neighbours offered to take anyone in, she says, and they were later housed in the community hall, shuffling upstairs to get out of the way when the dances were held every Saturday night.

McMillan Island’s most recent floods took place in 2007 and 2012. Fallardeau-Gludo, who now lives on higher ground, says she would never live on that island (which is still unprotected by dikes) again. She’s lost family members to the river and she’s worried for people who have built big houses. “That river roars; it is so foamy, so fast,” she says.

The lack of protection for First Nations reserves is seen a serious problem by environmental consultant Rene Crawshaw. Crawshaw’s family arrived in Chilliwack three generations back and his grandfather built a house six years before the 1948 flood. Like the Shxwhá:y, his family home is on the wrong side of the dike. Crawshaw is one of a group of citizens protesting Chilliwack’s latest plans for upgrading the dikes: instead of continuing a dike along the river’s edge (which would help protect three reserves along with others like him), the city is considering extending a zig-zagging wall of gravel. This wall would be located in front of dozens of homes along a jumble of streets on town land. Homes, businesses and graveyards on the reserves— just metres away—will be left on their own to survive when the flood comes.

Shxwhá:y CEO Sam says that the community has partnered on feasibility studies in the past with other levels of government, and he knows that building a brand new dike to protect them won’t be cheap. The Chilliwack Times reported that according to city staff, the cost of protecting the handful of houses on Sam’s and the other reserves could be more than $50 million. “With so few houses, we’re a low priority,” Sam says. If the city, the neighbouring First Nations and the federal government don’t come together soon, Sam says his community will have to take things into their own hands.

IN THE NETHERLANDS—much of which is below sea level—the Dutch have developed a $3.3 billion plan, known as “Room for the River,” which is shifting flood protection away from the age-old solution of raising dike heights. The plan’s alternatives include moving dikes farther back from the riverbed, creating development-adjacent canals for high-water periods and lowering the riverbed. To achieve this, residents have had homes demolished, relocated or raised, and farmers have had to move their crops. The idea isn’t to stop the water, which will eventually come, but to develop areas with floodwater in mind. Other solutions from around the world include constructing flood-proof homes that don’t allow water in, or ensuring critical electronics and system equipment are not housed below flood levels. These fixes aren’t cheap or easy, but they are forward-thinking, making areas resilient rather than resistant to flooding.

Former dike inspector Peters says that BC has a lot to learn from the Netherlands. “On a governance level, we’ve only been dealing with floods in British Columbia for just over one hundred years,” he says. “It’s not long enough to form our psyche around the best way to do things.”

Prior to 1975, Peters says, there wasn’t even any legislation about development in floodplains. Then in June 1972, a brand-new subdivision in Kamloops was inundated by the North Thompson River. Old photos show families in small boats trying to retrieve goods from their yellow-sided split-levels. Luckily the event took place midday when people weren’t asleep.

This catastrophe led the province to create new legislation requiring anyone building within new subdivisions in floodplains to apply for a permit and follow strict regulations. But in 2003, the province backtracked, passing on the responsibility for approving development in floodplains to municipalities. Furthermore, Peters points out that provincial guidelines—such as the one requiring that foundations be built on raised ground, or the one stipulating the distances a building must be back from a watercourse—are only guidelines and not required by provincial law.

The FBC hopes that a multi-jurisdictional flood management strategy will achieve some creative solutions closer to home, and the provincial government has committed $1 million to help realize this goal. For his part, Peters says the Lower Mainland could address its flooding concerns with a Netherlands-style big idea that could stop the problem at the source. First conceived of in the 1970s, the McGregor diversion project proposed the development of an upriver dam that could redirect some of the Fraser River’s waters to the Peace River during high-water times, diminishing the flow so that the dikes downstream could better withstand what was left. Although it was deemed unacceptable due to the impact on fish habitat and other environmental concerns, Peters says this type of project is still relevant today. Without a backup plan, Peters says, we’ll be left with an uncontrolled river and insufficient dikes.

AFTER THE RIVER RECEDED in 1948, people returned home to find their fruit trees destroyed and their chickens dead. Family heirlooms and photographs were gone forever. Mildew and mould climbed walls. The stench was awful. The damage was heartbreaking.

According to Peters, the way forward in British Columbia is clear: “The geography of the Fraser Valley doesn’t give us a lot of choice,” he says. “It’s either the valley floor or the mountainsides.” In other words, the people living in the floodplain are there to stay. Municipal, federal and provincial policies should, therefore, enshrine flood protection into its most basic governance and planning departments—and this includes big-ticket projects as well as ongoing flood management strategies, such as ensuring all new construction is built above flood levels.

Peters recommends that people who’ve never witnessed a flood before educate themselves. It’s up to us, he says, to decide whether we’re comfortable with the risk. But it’s also up to our governments to put a larger plan in place. Otherwise, when the big flood comes, we may follow in Betty Mitchell’s footsteps, finding out that putting things up a little higher just won’t do.

In the conclusion to her comprehensive history of high water on the Fraser River, K. Jane Watt writes that the solutions are as complex as the problem, often illuminating an “irreconcilable debate” between “polar opposites”—settlers versus First Nations, environmentalists versus developers, humans versus ecology. Watt emphasizes a different, but equally important, priority: a return to water consciousness. “Just as it’s in a river’s nature to flood,” she writes, “it’s human nature to forget what floods can do.”