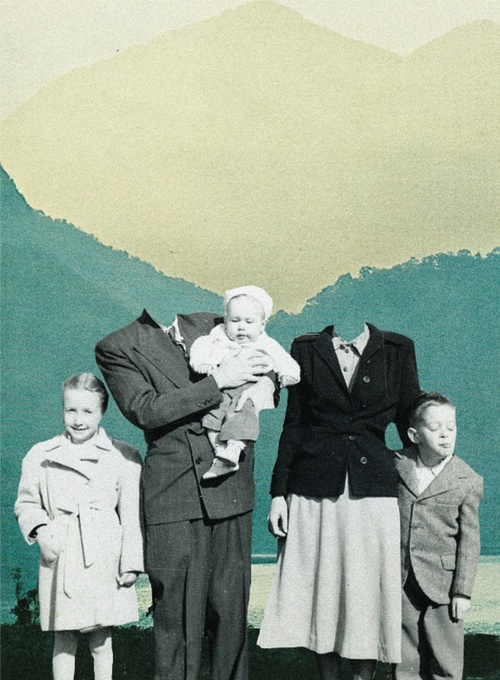

Illustration by Holden Mesk.

Illustration by Holden Mesk.

Black Market Babies

Religious matching and lax anti-trafficking laws led to a booming underground market for infants in mid-century Montreal. Adam Elliott Segal, the son of one such adoptee, investigates.

In February 1954, a fifty-one-year-old Outremont lawyer named Louis Glazer sat, crestfallen, on a bench in a Montreal police station. He’d just been arrested at 1288 Bellechasse Street, the home of Madeleine Bernatchez, after a yearlong sting operation jointly executed by the Montreal and New York City police departments. In the Montreal Star, the Saturday morning headline read: “Police ‘Buy’ Infant With Marked Bills.”

Sixty years later, on the final day of October 2014, six women gathered in the Tottenham, Ontario home of Reva Brownstein. A documentary crew from the French mini-series Le berceau des anges (“The Cradle of Angels”) began setting up in Brownstein’s sunken living room. Outside, a light rain fell. A mix of nervousness and anticipation filled the air—several of the women had never told their story on camera before. Travelling from as far away as Florida and Vancouver, the women shared one thing in common: seven decades ago, each of them had been born in Montreal and then adopted by Jewish families. It was the first time all six women had been in the same room after decades of correspondence and individual meetings. In many ways, these women had become a surrogate family for each other.

My mother, Esther Segal, was one of these women. After seeking out her origins twenty years ago, she discovered that she was one of thousands of infants sold to unsuspecting Canadian and American Jewish families by a complex network of Quebec-based baby smugglers, lawyers, doctors and illegal maternity home operators. In the years following the Second World War, these colluders had identified a marketplace of unwed pregnant Catholic girls and childless Jewish couples that could be manipulated for profit.

Glazer’s arrest, along with the arrests of thirty-four-year-old lawyer Herman Buller and sixty-four-year-old baby courier Rachel Baker, launched the trafficking of children into the national spotlight, exposing an illegal black market adoption trade that had operated in Montreal with impunity for over a decade. Their trials took place in 1955 and 1956, but federal or provincial law changed little in the immediate aftermath, and the story remained dormant for half a century—until my mother, and others like her, prompted by the death of their adoptive parents and the emergence of the internet, began searching for their birth families.

In 1940s Quebec, lax anti-trafficking laws meant it was not illegal to buy or sell children; at the same time, though, adoption laws were restrictive, ghettoizing Quebec citizens by religion. “Religious matching,” a term coined by McMaster Professor Karen Balcom in her book The Traffic in Babies, decreed parents could only adopt within their own faith. Quebec was 85 percent Roman Catholic at the time, with a small but growing immigrant Jewish population. With an oversupply of unwed pregnant Catholic girls and an undersupply of Jewish babies to adopt, the city—rife with post-war corruption, handling adoptions via a murky blend of church and state—became the perfect place to sell children.

My mother was born on January 7, 1946, an unseasonably warm day in Montreal. Approximately one week later, she was sold for $10,000 from a makeshift maternity home on Avenue D’Esplanade operated by Dr. Phineas Rabinovitch in what is now the Plateau neighbourhood in Montreal. Her parents had learned of Rabinovitch from friends who’d purchased their own baby girl four months earlier. Both in their forties, they traveled by train from Edmonton to obtain her.

The black market adoption of thousands of babies throughout Canada and across the US border took more than half a century to resurface. It required the birth of the internet age and technological advances in DNA analysis to crack open a window into what may be the seamiest era in Montreal’s history.

A few weeks after September 11, 2001, I met my mother Esther and my sister, Michelle, in an Italian restaurant at Prince Arthur and Park in Montreal. My mother, who’d flown in from Vancouver, spent most of lunch crying; at first, I thought it had to do with her post-9/11 fear of travel, but slowly I realized that her tears had to do with where we were. Until that day, I’d considered her adoption more like a blemish than a scar. It hit me: everything that had come before her birth was a blank space, a history crossed out, an ancestry we couldn’t access. My sister and I, my mother said, were her only living relatives, the only real proof that she existed.

Four years earlier, in late 1997—six years after her mother Rose passed away—my mother had typed “Adoption, Montreal” into a search engine. Several years of correspondence with social service agencies in Quebec had yielded no information about her adoption. By all accounts, it had never taken place.

My mother was not the only one. In Ann Arbor, Michigan, a woman named Donna Roth—born in Montreal in 1946, the same year as my mother—had also been seeking her roots. Connecting online through a national adoption organization called CANAdopt, remarkable details emerged once the two of them began emailing. “Something strange is going on,” my mother remembers thinking. In addition to their shared age and birthplace, both were raised Jewish, my mother in Edmonton and Roth near Detroit, and both had physical characteristics that belied their parents’ European Jewish background. (Roth often heard from friends and family that she looked like a shiksa because of her blue eyes and fair skin; as a baby, my mother’s hair was blonde.) Neither was listed in Batshaw Youth and Family Centres’ database, the organization that administered all Jewish adoptions in Montreal.

My mother and Roth became fast friends, and hatched a plan to visit Montreal together. My mother contacted a Dawson College professor she grew up with who happened to share a gym with a local reporter. On the day before Mother’s Day in 1998, along with several women from Ottawa and New York, they appeared side-by-side in the Montreal Gazette holding baby photos. Others began emerging from the shadows, all with similar stories of births outside traditional hospitals, parents that raised them out of province, and no official adoption papers. Some had learned their price tags, which ranged from $3,000 to $10,000, and they shared this information with the paper.

When my mother’s story appeared in the media in 1998, a light bulb went off for Harold Rosenberg. One name in the article stood out for him: Rachel Baker, the baby courier.

Rosenberg, a native Montrealer whose black market adoption occurred in 1949, is grateful despite the circumstances surrounding his birth. “We could have ended up Duplessis orphans,” he says, referencing a state-sanctioned 1950s practice where orphaned children in Quebec were labelled inaccurately as mentally ill, physically and sexually abused, and subjected to medical experiments. (In return, the Quebec government received extra funding by renaming these homes health-care facilities.) To Rosenberg, growing up in a Jewish home was a godsend. But it also ripped a crater-sized hole in his identity when, as an adult, he discovered not only that he was adopted, but that he’d been purchased in a taxi outside a Montreal hospital.

Baker, Rosenberg had learned, was most likely the woman who dropped baby Harold off to his adoptive father in 1949. “[My father] was waiting in a cab, she gave me to him, he gave her the money—goodbye, good luck,” Rosenberg told the Montreal Gazette in a follow-up story. Six years after Rosenberg’s father handed Baker $1,800, she was arrested for cross-border smuggling—but if Rosenberg’s parents learned of her arrest, or made the connection, they took their secret to the grave. Until Rosenberg was in his thirties, all he knew was that his forty-five-year-old mother had given birth to a “miracle.” His parents never wanted him to feel different in the mostly Jewish neighbourhood of Notre-Dame-de-Grâce where he grew up. But something about Rosenberg’s identity had never felt quite right, and, in 1984, a loose-lipped relative let the truth slip at a family gathering. Rosenberg started asking questions. None of his other neighbours or family members were surprised when Rosenberg declared the bombshell news of his adoption. “Everyone on Ball Street knew the truth,” he says. A week after the gathering, Rosenberg’s cousin remembered the last name Baker. The detail meant nothing for fourteen years until May 1998, when Rosenberg opened the Saturday newspaper and read the story on black market adoptees.

Five days later, Rosenberg posed in its pages holding his forged birth certificate. With the help of a private investigator, he started searching, as did my mother, Roth, and dozens more interviewed for this story, stitching the pieces of their mysterious personal histories together. Over the next several years, they would acknowledge and accept the truth—that men like Buller and Glazer had colluded with doctors, falsified birth certificates, registered babies with the rabbinate and pocketed cash fees from families desperate to adopt. While these revelations provided a framework to a lifetime of unknowing, they also opened Pandora’s Box to a host of identity-related issues. Three decades later, for many black market adoptees, the lid remains open.

Before bagel shops and smoked meat sandwiches made Montreal’s Jewish neighbourhoods a tourist destination, before Mordecai Richler immortalized the St. Urbain Street Jewish Ghetto in The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz, the Plateau was a thriving shtetl-like community at the beginning of the twentieth century: garment factories and clothing shops, kosher meat hanging from butchers’ hooks, barrels of pickles and herring sitting storefront and the ubiquitous sound every morning of the “clopping of horses’ hooves,” as Joe King writes in From the Ghetto to the Main.

King fails to mention the other item for sale on the block. Dr. Rabinovitch’s makeshift maternity home—where my mother believes she was born—is now a bed and breakfast called Casa Bianca. Its website describes the property as an “architectural landmark” built in 1912 made of “unusual white glazed terra cotta tiles” and built in “French Renaissance revival.” It also notes: “The house is famous to older locals, Jewish and not, many of whom still knock on the door to visit the place where they had tonsils removed.”

Dr. Phineas Rabinovitch was one of five brothers, four of whom became doctors. His younger brother Sam famously resigned in 1934 as chief intern from the Notre-Dame Hospital following an anti-Semitic walkout by Catholic doctors in hospitals across the city due to his appointment. Phineas’ moral compass was, to put it mildly, not as well-honed as his brother Sam’s. Aside from my mother, several others believe they were born and bought at Rabinovitch’s clinic, including Reva Brownstein, featured in Le berceau des anges, who says her father paid $15,000 to adopt her, and Harry Getzler,* a Toronto-based physician.

Getzler met Rabinovitch twice, first in 1959 as an eighteen-year-old. They met in Rabinovitch’s small office, located just down the street from the clinic on the corner of Marie-Anne and Esplanade. “I wanted to know who my parents were, and if they were Jewish,” Getzler says. His adoptive parents in Ontario knew little about his birth parents, and were “disturbed” by their son’s questions. Getzler will never forget the first thing the doctor said in their thirty-minute conversation: “What did they tell you?”

Rabinovitch told Getzler that his birth father was a factory owner. When Getzler pressed the doctor about how many adoptions he had overseen, Rabinovitch claimed he’d presided over just four births, including one girl the doctor adopted himself.

Unsatisfied, Getzler returned ten years later for answers—but the doctor became more evasive. He changed the story about Getzler’s birth father’s occupation and refused to reveal Getzler’s birth parents’ identities. In a total non sequitur, Dr. Rabinovitch bragged about how wealthy he’d become, an admission that shocked Getzler. He came away suspecting that Rabinovitch, who’d been described to him by a former employee as “despicable,” had arranged the adoption of far more than just four babies. So Getzler sought legal representation.

In 1979, several years before Rabinovitch’s death, Getzler’s lawyers received a response from the doctor’s legal team. “[Dr. Rabinovitch] has informed us that you are seeking to obtain information concerning your natural parents,” the letter read. “We have discussed the matter with him and it is our position that Dr. Rabinovitch is not required to disclose any information that may have come to him concerning your adoption.” This denial is as close to an admission of the doctor’s complicity as anyone would get.

While Rabinovitch’s name shows up in voting and census records, there is no mention of him in the media, Louis Glazer’s court transcripts, or any of the subsequent US Senate Subcommittee meetings on Juvenile Delinquency, which took place from 1953 to 1956 and sought to legislate and potentially prosecute black market adoption at the federal level. The proposed bills failed and baby sellers in Montreal were back in business by 1959, according to evidence given at the Report of the Joint Legislative Committee on Matrimonial and Family Law in New York. Rabinovitch was never arrested. Knowledge of his alleged involvement in selling children for profit is predicated, instead, on the oral testimony handed down by the adoptive parents of Brownstein, Getzler and others to their children.

Brownstein’s father—nearly fifty years old and a wealthy manufacturer of military uniforms during the war—received a phone call from his pediatrician in late October 1946 informing him that a baby girl had become available for adoption. Her father filled an envelope with $15,000 and hailed a Diamond taxi, which pulled up outside of Rabinovitch’s maternity home. He handed the money to a woman, and got right back into the same cab, now holding baby Reva wrapped in a blanket. It all happened so fast that Reva spent the first several days of her life sleeping in a drawer as her mother scrambled to find a crib.

Brownstein discovered her origins in 1965, when she had a stroke at the age of nineteen; her father, who told her that she was “the best investment of [his] life,” couldn’t provide any medical history to draw upon. Much like Getzler, Brownstein had no reason to suspect at the time there were others like her.

Stymied by his dealings with Dr. Rabinovitch, Getzler spent the next thirty-five years chasing false leads. When he finally signed up for DNA testing last year, Getzler’s mitochondrial DNA (the female side) matched with a non-Jewish half-niece in California. But the remaining YDNA matches (the male chromosome) on his ancestral tree are, incredibly, all Jewish, meaning his birth father was in fact of Jewish descent while his birth mother was not. Getzler, who has corresponded with several paternal Jewish cousins, believes he’s closer than ever to finding the identity of his birth parents. Like many black market adoptees, it’s been a lifelong fascination to discover what really happened. “I’m not sure how much it really changes your life,” Getzler says, “but it’s important that we’re still doing it. It helps with the trauma.”

In 1871, according to Joe King, just 518 Jews lived in Montreal—mostly well-to-do “uptowners,” predominantly English-speaking and living in either Westmount or Outremont. By 1901, the Jewish citizenry had ballooned to fourteen times its 1871 size, numbering nearly seven thousand residents. In another ten years, the Jewish population quadrupled to twenty-eight thousand.

The new immigrants were poor Yiddishers, “downtowners” who crowded around St. Laurent Boulevard, now known as the Main. Most had escaped violent Eastern European pogroms and their emigration changed the makeup of Jewish culture in Montreal overnight, as many of these newcomers spoke little English and no French. In 1863, Lawrence L. Levy founded the first Jewish social service agency in Canada, eventually named the Baron de Hirsch Institute, to help unmarried Jewish men connect with the small community. The society would be instrumental in assisting with the influx of European Jewry, and the name Hirsch became synonymous with Jewish Family Services, orphanages, libraries and schools across the city, and the Baron’s name still adorns the largest Jewish cemetery in Montreal.

Now known as Batshaw Youth and Family Centres, the Baron de Hirsch Institute was the conduit through which all Montreal Jewish families pursued adoption in the early half of the twentieth century. By the late 1930s, the waiting list to adopt Jewish children was unbearably long, and above-board adoption in Montreal or New York was near-impossible.

Couples desperate to start a family looked elsewhere. In 1954, one father outlined his story in a Weekend Picture Magazine article called “We Bought a Canadian Baby.” Only one Jewish child during a twelve-month period had been put up for legal adoption in a borough adjoining New York City; though the American and his wife applied to state agencies in Trenton, Newark and Chicago, Jewish babies simply weren’t available. They were put on a waiting list and told it could take years. Like many dejected couples before them, they soon heard of another way.

In the back rooms of makeshift maternity homes and “baby mills” scattered across Montreal, young, unwed Catholic girls were arriving in droves. According to Balcom, the church’s harsh condemnation of sex outside of marriage made it difficult for Quebecois women to keep children born out of wedlock, and the law of “religious matching” meant a surplus of Catholic babies existed. Unsurprisingly, many of these young Catholic girls did not go through legal adoption channels.

Only one in eight unmarried women who gave birth at one Catholic hospital in Montreal, Balcom writes, kept their child. Many sought refuge underground, giving birth in secret in the unlicensed homes of Sarah Weiman, who ran a maternity home on Laval Street, or Dr. Phineas Rabinovitch. Doctors presided over the births, and then lawyers such as Herman Buller and Louis Glazer drew up the paperwork, while Rachel Baker and “pappys”—smugglers—helped transport children across the city or over the border.

Clients came from Michigan and New York, and in my mother’s case, as far west as Alberta. At least twelve baby mills proliferated in and around the city of Montreal, according to one official quoted in the Montreal Gazette four days after the sting operation in 1954. Some of these employed “spotters” or “leg-men,” who would search for vulnerable pregnant women on the street and in bars. One rival gang even stole a newborn from another trafficking enterprise.

While the couple from “We Bought a Canadian Baby” realized their dream of becoming parents, it came at incredible moral, emotional and financial cost. The man, who’d obtained a sickly child from Sarah Weiman, later testified to the US Senate Subcommittee of Juvenile Delinquency that her home was like something “out of a Dickens novel.”

In his 1956 testimony at the same meeting, Eugene Moyneur, a former boxer and circus worker who worked as a “pappy” for Weiman, bristled at lead investigator Ernest Mitler’s suggestion that he was a smuggler. “How much money did (the parents) give you beforehand for smuggling the child into the United States?” Mitler asked Moyneur. “You call bringing in a baby smuggling?” Moyneur replied. “That ain’t smuggling, mister. They gave me $350. That is giving a baby a home.”

Mitler began investigating and prosecuting black market, cross-state adoption as early as 1949. In 1952, a New York City woman approached the DA about the legality of her child, naming Buller as the Montreal contact who arranged the adoption. (Following Buller’s arrest at the Montreal airport, Le Devoir referred to him as “le tsar international des vendeurs des bébés”). As described in the Montreal Gazette, Mitler interviewed over seventy American couples that had admitted buying children from Montreal and presented his initial findings to the Joint Legislative Committee on InterState Cooperation in New York. In 1954, following Buller and Glazer’s arrests, Mitler described many of the parents as “gullible” to the Montreal Gazette; the district attorney believed it was possible many never knew the extent to which they’d been lied to about the provenance of their children. They were caught in the middle, along with the young, desperate birth mothers from Quebec, whom Balcom writes were given “anonymity, free board, some form of medical care and adoptive homes for their children.”

Those who made a fortune connecting pregnant women with childless Jewish couples ultimately faced little consequence. When Baker was arrested in late 1955, the Canadian Press reported that she screamed, in the Federal House of Detention in New York, “I want to die… you’re killing me, give me the electric chair.” Charged with “conspiring to sell a baby to a childless couple and to arrange an adoption of a child without being an authorized agent,” the sixty-four-year-old woman, described by the Associated Press as short, plump and bespectacled, received a six-month suspended sentence and spent four months in a New York City workhouse before returning to Montreal. Buller pled guilty to falsifying a birth certificate, spent one day in jail and was fined $2,000, and Glazer was acquitted thanks to a bulldog criminal lawyer named Joseph Cohen known for taking on cases of Montrealers accused of serious crimes, including notorious Jewish gambling boss Harry “the Boy Plunger” Ship. After his conviction, Buller fled to Ontario with his wife and in-laws and spent the following years teaching English and writing political novels set in Montreal. Glazer continued practicing law until his death in 1975.

My mother’s birth certificate lists January 7, 1946, but four days later, on January 11, my grandmother Rose was photographed with relatives in a popular New York City nightclub, Zanzibar. Rose was waiting in New York for a phone call from Dr. Rabinovitch or a Montreal lawyer. She and my grandfather Morris, a successful dry cleaner in Edmonton, paid Rabinovitch $10,000 (over $140,000 in today’s dollars) according to Rose’s sister-in-law, who disclosed the sum following my grandmother’s death in 1991 (Morris died in 1955). My great aunt claimed to have no knowledge of Rabinovitch or his clinic, and my mother’s parents never detailed how they acquired her. Her birth was registered at the Young Israel of Montreal Congregation, which then passed the birth record on to the province. “Even though false birth registration was the foundation of the ring’s operation,” Balcom writes, “there was never any public accusation that rabbis were aware of the deception or consciously involved in fraud.” An American investigator questioned one rabbi on the subject who naively opined, “Jewish girls were ‘going bad.’”

A certificate of judgment arrived in Edmonton at the end of 1946 from the Superior Court of Quebec recognizing the adoption. Yet when my mother wrote to social welfare organizations, beginning in 1993, the answers all came back the same: we have no record of you. “It does happen, particularly in cases of private adoption, that no Social Service Centre has any records,” one social worker wrote her.

Before DNA testing became widely available, genealogists, researchers and “search angels” in Quebec vigorously searched for paper trails for private adoptions like my mother’s, the search doubly hard in a province with closed adoption records. Many black market adoptees lacked a smoking gun—the name of their birth mother, for example, or a hospital. Even when my mother found her birth date recorded on microfilm inside the Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec—a painstakingly laborious process—and received a letter from the synagogue that registered her birth, she remained in limbo. Initially promising, these breadcrumb trails eventually petered out. The hope remains that a ninety-year-old rural Francophone woman—one who walked through Dr. Rabinovitch’s doors at the end of 1945, eight or nine months pregnant—is still alive. Finding her, or anything about her, has been my mother’s goal for the last twenty-five years.

Those of us who aren’t adopted often take for granted that we have a right to know who we are and where we’re from. For adoptees born in provinces with closed records—both the birth parent and adoptee must consent to “identifying” information being shared between parties—government obstruction adds a further layer of obfuscation. While Saskatchewan passed open adoption legislation on January 1, 2017, Quebec, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and PEI still lag well behind Canadian and world norms. When trying to piece together a past steeped in secrets, it’s far more advantageous to have been put up for adoption in British Columbia, Scotland or Australia, which have had open records for decades, than in a Catholic-dominated province such as Quebec, where the Montreal Gazette estimates 300,000 adoptions occurred between 1920 and 1970.

One in five Canadians—seven million of us—are affected by adoption, according to the Adoption Council of Canada. While DNA information from sites such as 23andme.com, FamilytreeDNA.com and Ancestry.com has democratized our ability to trace our ancestral identities globally, it’s being utilized as an even more valuable tool for adoptees seeking their birth family. This kind of biological science can also provide evidence of familial or non-familial ties in a judicial context; such evidence played a crucial role in recent international baby trafficking and adoption scandals in Chile and Spain.

Justice Minister Stephanie Vallée introduced Bill 113 in October 2016—a bill that promised to remove “total secrecy” and presented amendments to Quebec’s Civil Code and the Youth Protection Act. But there’s reason for skepticism—Quebec has been historically slow regarding child welfare. The province did not have a Children’s Protection Act until 1977, for example, some fifty years after most Canadian provinces enacted such laws; previous attempts to update adoption laws had died on the vine in 2009 and 2012. Nonetheless, the reality for my mother and other black market adoptees is that a change in law would do little to help—their birth papers, buried deep inside the city archives, are forgeries. If the past is a blank page, where do you even begin?

“For black market adoptees, you have to do DNA,” Annie Carlile says. Carlile is a search angel based in California who specializes in provinces with closed adoption. She believes Batshaw, which administers adoption information for the Anglophone and Jewish communities of the island of Montreal, is “trying really hard” but can still do much better. “They call it, ‘the one phone call,’ the one contact with the birth parent,” Carlile says. “If that birth parent says no, they close the file. That’s it. That makes it really scary for the adoptee—they only get that once chance, that one window. It’s so barbaric.”

When Bill 113 was introduced in the fall of 2016, Patricia Carter, founder of the Facebook group Open Adoption Records in Quebec, wrote that Bill 113 was flawed and should be rewritten. Carter advocates for consultation with adoptees, adoptive families and birth families, and wants to see the bill’s veto clause—which allows for birth parents to reject both contact and identifying information being shared—removed altogether. “When you go to any kind of doctor with health concerns, you’re always asked what your family medical history is,” Carter says. “Everybody who needs to have any medical procedure needs to know for safety’s sake. Putting a veto in place won’t allow you access to that.”

Caroline Fortin, president of Mouvement Retrouvailles, a non-profit adoption organization founded in 1983 with over 13,500 members (including my mother) is more hopeful about Bill 113. “It’s not perfect, but it’s a big step,” Fortin says. “It will be a good thing for adoptees. Not for all, but for many.” She believes social workers’ attitudes have matured and Quebecers are growing increasingly more open-minded. In the last two years her organization has matched sixteen birth families. Sixteen is a drop in the bucket when compared to how easy it is to use DNA kits and genealogy websites to track down family, but Fortin warns it can be “dangerous” to contact a birth parent without taking a cautious, open-minded approach. Leaning on the emotional and administrative support of skilled social workers avoids the pitfalls of ambushing potential relatives on social media.

“The biggest challenge is rejection,” says Carlile. The search angel is part genealogist and part detective, and guides the adoption triangle—birth parents, adoptees, adoptive parents—through paperwork, DNA testing and reservations about contacting potential family members. Through her page, the Free Canada Adoption Page, Carlile estimates that she’s helped thirty to fifty families.

Manuella Piovesan, the program manager of adoption at Batshaw Youth and Family Services until her recent retirement, received hundreds of adoption-related search requests each year. That will increase if Bill 113 passes. Opening adoption records will likely strain staff and resources, according to Piovesan. Provinces such as Saskatchewan, Manitoba and Ontario were “inundated” during the yearlong media blitz prior to the laws going into effect, she adds. Despite frustrations echoed by the adoption community that Batshaw is falling short—Carlile is critical of how quickly they close case files—Piovesan seemed conscious of Batshaw’s responsibility to adoptees and birth parents, and optimistic about the future of their services at the time of our interview. “We have access to databases and resources we didn’t have ten years ago,” she says. “Clinical research indicates birth mothers are often more at peace [when they] make an adoption plan and are in touch once a year with the adoptive parents, and know how their child is doing. The feedback and literature indicates [outcomes in these circumstances are] more positive than when we have closed adoptions.” Batshaw, however, has no official position on the benefits of open versus closed adoptions.

Twenty years ago, the black market babies became inadvertent advocates for open adoption records in a province that has long pitted the rights of parents against children. But little has changed since then. “Everyone has a right to privacy,” Minister Vallée’s spokesperson says. “As a result, Bill 113… has been adjusted to balance the previous social pact—respect for the privacy of parents and the need for individuals to know their origins.” As the bill stands, birth parents wishing to file a contact veto will have to do so within one year of the law passing, or within the first year of the child’s life. Adoptees with deceased parents must wait twelve months to access their names. Vallée’s spokesperson insists Bill 113 is a “priority.” Yet on the first day of hearings, this past November, Vallée is quoted in the Montreal Gazette as saying, “I want to let everyone express themselves on the bill as it is right now and then we’ll see.” In January, the government nearly prorogued and the bill has been benched for the remainder of 2017. Time is not a luxury that older adoptees have.

Harold Rosenberg is accustomed to the drama and disappointment surrounding adoption in Quebec; he acknowledges Bill 113 won’t change much for people like him. But he also knows surprises lurk around every corner. For over thirty years, Harold’s cousin Moe kept a secret about a baby bracelet, a bracelet that would change Harold’s life forever.

Harold’s adoptive mother received a phone call the day he was born in February 1949. Rachel Baker, who was at the hospital, told Mrs. Rosenberg a baby would be available the following day. Mrs. Rosenberg, who didn’t drive, had cousin Moe take her for a quick visit. “Going to the nursery, we passed a room with a patient in it,” Moe recalls in Past Lives, a documentary filmed in 2004 about Rosenberg’s story. He recognized the patient from the neighbourhood. “[She] looked familiar to me, but I just passed by.” Mr. Rosenberg took baby Harold home the next day.

When his father died in 1963, Harold’s mother asked Moe to drive her to the bank to clean out the safety deposit box. That’s when Moe saw the baby bracelet. It read “Boyko.” He remembered the patient in the hospital and realized she must be Harold’s birth mother. Later that day over a cup of tea, Mrs. Rosenberg pulled out a pale blue prayer book and swore Moe to secrecy about the contents of the box. Even after Harold discovered his adoption in 1984, Moe kept silent for fifteen more years before the Gazette story finally prompted him to tell Harold the truth about the bracelet. Armed with a name and confirmation of Baker’s involvement, Rosenberg, who had worked as a crime photographer, tapped his connections in the police department. The investigator had bad news. Harold’s birth mother, Mary Boyko, was dead. But her son, Harold’s half-brother, was alive and living in Ontario. He and Harold met for the first time in the Montreal airport in 2004, an experience Rosenberg told the filmmakers was “surreal” but also inspired a “feeling of elation.” In the final scene of the documentary, following a Jewish custom, he places a rock on Mary Boyko’s grave.

In the early eighties, Marilyn Cohen,* another black market baby, successfully petitioned the Superior Court of Quebec to release her birth certificate on medical grounds. She spent the next two decades knocking on the doors of strangers, searching for “Miriam Levy,*” the “spinster” named as her birth mother.

A DNA test in the early 2000s proved Cohen possessed no Ashkenazi Jewish blood and that “Miriam Levy” had never existed; the name on the certificate was fake. It has been difficult for Cohen to accept that she was not born to a Jewish mother. (According to orthodox halachic law, to be considered Jewish, one must have a Jewish mother. Should Jewish children of black market adoptees wish to marry an Orthodox Jew, they might have to convert to their own religion if the rabbinate discovered the truth of their mothers’ origins, though this has not yet happened.) Raised Orthodox and married to a rabbi, Cohen’s Jewish identity has been an integral part of her life.

In the past two decades, Cohen has signed up for every DNA test out there. Matches were few—until recently. Cohen took the Ancestry.com DNA test when it became available in Canada last summer, but neglected to check her account for months. When she finally logged in on January 4, 2017, a four-month old message was waiting for her. “I nearly fainted,” she says.

Cohen’s DNA had matched with a younger Francophone woman living in Montreal. After years of disappointment, Cohen had learned to keep her hopes in check. When the two uploaded the “raw data” to GEDmatch, it came back positive—this woman was undoubtedly Cohen’s niece. Cohen has since learned she has two siblings. In late February, she met another niece and nephew just outside of Toronto. For someone who “never looked like anybody,” Cohen started crying when they told her she looked like their grandmother. Cohen discovered that her birth mother passed away in the nineties, but at the very least, she finally knows her mother’s real name.

One afternoon last December, I had lunch at Beauty’s, a Jewish-owned luncheonette on Mont-Royal, in operation since 1942 and just one block from where my mother was born. I sat at the counter and wondered if Dr. Rabinovitch, in-between delivering babies he would later sell for profit, ever did the same.

To be one thing but know you are another is a strange idea; the unknowing can be emotionally precarious territory. My father is Jewish, and for half my life, Jewish identity wasn’t a question, but a given. But that’s all changed as my mother continues unraveling the tapestry of her past through technology. She has learned she is a panoply of British, French and Iberian heritage and that her ancestors were Acadians from New Brunswick. She shares distant DNA with several black market babies, and they affectionately refer to each other as “cousins.” Those friendships salve whatever isolating feelings exist when answers remain unknowable—like many born during that shadowy era of Montreal’s history, my mother may never know why she was born seventy-one years ago in a doctor’s office underneath the silhouette of Mont Royal, who her birth mother was, and what choices led her to the clinic. Though DNA may never provide this why, it does, at least, provide a where. For now, my mother has my sister and me, and that may have to be enough.