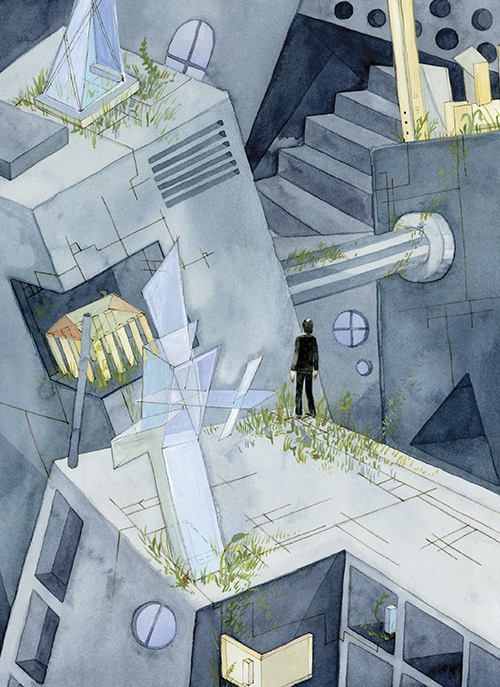

Illustrations by Jensine Eckwall.

Illustrations by Jensine Eckwall.

Everyone's a Critic

Corridart was designed to showcase Quebec artists during the 1976 Montreal Olympics. But, as Taylor C. Noakes writes, one very important person was less than impressed.

JULY 13, 1976, WAS A TUESDAY. That evening, Montreal's Saint Catherine Street, then the city's epicentre of nightlife, was bustling. The opening ceremonies of Canada's first Olympiad were scheduled for the following Saturday. For the second time in a decade (Expo 67 preceded the Games by nine years) all the world's eyes were on Montreal.

The city was electric with possibility, many citizens were excited and optimistic. New construction was redefining the skyline, the Metro was being expanded and the world’s largest airport had just opened north of the city. Police on motorcycles sped down Sherbrooke Street, ferrying athletes and officials to the Olympic Park in Montreal’s East End. Sixteen thousand military personnel—then the largest peacetime deployment in Canadian history—had fortified the city against threats both real and imagined (the last two Summer Games had witnessed unspeakable horrors: student protests against the Mexican government led to the Tlatelolco massacre ten days prior to the opening of the 1968 Summer Games, and at the 1972 Munich Olympics, the Black September terrorist group murdered eleven Israeli athletes). Given the massive costs associated with hosting and the ever-present possibility of a terrorist attack, the future of the Olympic Games was in doubt. Mayor Jean Drapeau seemed determined that his city—his Olympics—would restore the reputation, prestige and commercial viability of the Games.

Ann and Melvin Charney had gone out that night to see a film downtown. Melvin, then a young professor of architecture at the Université de Montréal, was one of the leading voices of the city’s nascent architectural heritage preservation movement. In 1972, he organized the exhibit Montréal: plus ou moins? at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, which was an early critical assessment of the municipality’s urban planning. At the time, the city was considered Canada’s unquestioned metropolis, as distinct from other North American cities as one could be. In the exhibit, Charney had dared to ask whether the city’s new development was turning its back on its long-standing urban traditions in an effort to appear more modern, and by consequence, more flatly international. Though the exhibit had been controversial, Charney’s efforts to get Montrealers to see their city in a new light had raised his profile and ultimately borne fruit: Corridart, the main cultural component of the Montreal Olympics and Charney’s magnum opus, now stood a few blocks away from his theatre seat.

About halfway through the film that night, Charney’s pager went off. He and his wife didn’t know precisely what the alert meant, but the two hurriedly exited the theatre and made their way to Sherbrooke Street. During the quick journey, they crossed more than one hundred years of urban development: Victorian greystone triplexes wedged cheek-to-jowl with contemporary apartment towers, modernism thrusting up from the canopy of the more human-scale city that once was.

When they finally reached Sherbrooke, the Charneys witnessed the unimaginable: under police escort, city workers from the public works department were systematically dismantling Corridart. Posters and pictures were torn down one by one. Exhibits and installations were being ripped out of place, deposited into the backs of waiting dump trucks. There were enough police present to give a clear message: there would be no negotiations.

The Charneys looked on as a year’s worth of work came down around them. Melvin approached a supervising police of- ficer and identified himself as the man responsible for the project; he asked why city crews were dismantling the exhibits. The officer replied that they were simply following orders. Whose orders? Charney protested. The mayor’s, the officer responded. He'd given the go-ahead, the matter was closed.

AS ITS NAME IMPLIES, Corridart dans la Rue Sherbrooke was a corridor of art. Its twenty-two projects stretched nine kilometres, providing a conceptional link between the futuristic Olympic Park in the city’s east and its historic centre in the west. The project was funded by a $386,000 grant from the Quebec culture ministry and ad- ministered under the arts and culture program of the Comité organisateur des jeux olympiques (COJO), an agency of the provincial government.

Though Corridart had initially been conceived as a street festival, Charney developed the idea of turning Sherbrooke into a monumental open-air gallery where installations would interact with the urban landscape, cleverly reinterpreting the street’s historic role as a route for official processions by encouraging locals and tourists alike to casually walk its length and engage critically with its history. It not only intended to showcase the avant-garde of the Quebec arts scene to an international audience, it was further intended to provide free, homegrown entertainment for the tens of thousands of Montrealers who couldn’t afford tickets to what was one of the most expensive Olympiads in history.

IT WAS AT AN AFTER-HOURS session of the Montreal executive council on that same July 13 evening that Mayor Jean Drapeau and his colleagues ordered Corridart's demolition. Though the official justification was that the installations went against city bylaws and posed a danger to public security, municipal staff had been collaborating on Corridart since January 1976—about a month after the competition jury, headed by Charney, had selected the winning projects from the 306 submissions received. Everything had been approved through the proper channels, the whole process thoroughly transparent, and the city was involved every step of the way; officials even provided assistance in determining where some of the pieces would be installed, mindful of the needs of traffic. How had it suddenly become so dangerous? Two days later, Melvin Charney got his answer: an unnamed city official indicated to the Montreal Gazette that Corridart was torn down because it was considered “ugly and obscene.”

In that same article, artists denounced Drapeau’s act as “repression, vandalism, barbarism and stupidity.” Jean-Paul L’Allier, the provincial minister of cultural affaires, agreed with the artists, saying that Corridart had been funded by a provincial arts grant and Drapeau had far overstepped his authority. L’Allier ordered Drapeau to put everything back in its place immediately, even threatening legal action against the city. Drapeau simply ignored L’Allier’s attempts at contact, and staff continued to dismantle the project.

Workers started with the smaller installations, taking down the thematic continuity called Mémoire de la rue, which included seventy-one yellow scaffoldings hoisting posters, photos and vacuum-cast orange hands that pointed out Montreal’s landmarks, lieux de mémoire and major cultural institutions. By Friday, July 16, the largest installations, including Bill Vazan’s five hundred thousand pound Stone Maze—a place of rest and play on a traffic island in a park—had been removed from sight.

That Saturday, the day of the opening ceremonies, the little that was left of Corridart had been impounded in a municipal dump. While a few of the artists had been able to carefully dismantle and save their creations, most were damaged beyond repair or destroyed. Initially, artists were not even permitted to retrieve whatever remnants had been crated off to the dump. All they could do was look at the relics, which were left in clear sight of the main entrance gate.

THOUGH HE IS OFTEN REMEMBERED as being a visionary city builder, Jean Drapeau's Montreal has a mixed legacy. First elected mayor in 1954 at the age of thirty-eight, Drapeau played the role of the urban reform crusader, leading in slum-clearance initiatives. Despite a productive three-year term, he lost the 1957 election to Sarto Fournier, a favourite of conservative Quebec Premier Maurice Duplessis. But Drapeau would have another chance—when Duplessis died in 1959, his Union Nationale party, which had ruled the province for the majority of the previous two decades, imploded. Drapeau was re-elected to the mayoralty of Montreal in 1960, the same year Quebec marked the beginning of the Quiet Revolution with the election of the socially progressive Liberal government of Jean Lesage. He would remain mayor for the next twenty-six uninterrupted years, and, when he finally resigned without an heir apparent, left something of a power vacuum.

Aside from the Olympics, Drapeau is remembered for having successfully lobbied for Expo 67 as well as the establishment of a baseball team, the Montreal Expos. His accomplishments also include the creation of the city’s mass-transit Metro system and its main performing arts centre, Place des Arts. Outwardly it all seemed very progressive, but for some citizens, the golden age of the Drapeau Era was more of a gilded age. While the city’s built environment was beginning to look more modern, it had come at the cost of depopulation, environmental degradation and the destruction of much of the city’s historical and architecturally significant urban environment.

Drapeau’s slum-clearance initiatives in the fifties and sixties, which followed a prevalent urban planning theory of the day that deteriorating buildings deteriorated morals, led to the condemnation of entire neighbourhoods. Montreal’s former red light district was first to go, largely replaced by the Habitations Jeanne-Mance housing project. A portion of Chinatown was demolished and became the site of Complexe Desjardins. Drapeau even had the parks department cut down some of Mount Royal’s trees and underbrush when the police’s morality squad discovered that the area was a popular cruising spot for the city’s gay community. This was the other face of Jean Drapeau: mercurial, autocratic and single-minded.

Drapeau had promised an Olympiad that “could no more produce a deficit than a man could bare a child,” yet his Olympics were mired not only in massive cost overruns, but endemic complaints of corruption and outright fraud. Trucks laden with building materials intended for Olympics-related construction would routinely report at the site, take a lap around the block and then head off to a number of residential projects elsewhere in the city—the private initiatives of the consortia of Olympic contractors. There are more than a few apartments in Montreal suspected of being built with concrete originally purchased for the Montreal Tower, itself only completed in 1987, eleven years late.

The Games were originally estimated to cost about $120 million, but this figure increased ten times between the day Montreal was selected to host and the day of the opening ceremonies. Cost overruns and construction delays had become so problematic that by November 1975, the provincial government—after forcing Drapeau to testify in front of a commission investigating the now rocketing costs associated with the Games—took over in order to finish the stadium in time for the opening ceremonies. We’ve all heard the tale of the art-class bully who, acting out of frustration given his own lack of skill, destroys the creations of his more talented classmates. In the summer of 1976, after seeing the rise of the province’s Corridart, it seemed that the role was Drapeau’s to play.

DRAPEAU’S APPROACH to Montreal’s urban regenesis began to experience pushback from the citizenry towards the end of the 1960s, when residents from diverse backgrounds and neighbourhoods formed committees and associations to lead public protests against what they saw as reckless development. Their activities coalesced in opposition to several projects conceived during this time, including the demolition of the Van Horne Mansion to erect an office tower.

Though Melvin Charney was a professor, not an activist, he was sympathetic to the arguments and philosophies of the protestors, and was essentially part of the same larger community of urban bohemians. If Drapeau could be compared to Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Robert Moses, perhaps Charney’s goals were more akin to Jane Jacobs and Buckminster Fuller. It seems that Drapeau viewed Montreal, especially its most densely pop- ulated urban centre, as a clean slate on which his own legacy would be built. Charney, by contrast, was concerned that some- thing greater than the sum of its parts was being obliterated to serve narrow interests. Where was the home of Montreal’s soul? Where was creation cultivated? What were the physical forms and neighbourhoods of the counterculture, and given their general lack of resources, what could possibly protect the artist colo- nies from obliteration?

These questions were front and centre in Corridart, though that’s not to say Corridart was an indictment of the Drapeau administration per se. The projects chosen were wide-ranging and diverse. Teletron, by Michael Haslam, consisted of bright payphone booths that played music and animal sounds. Haslam also recorded a detailed budget for the Montreal Olympics (then the most expensive Olympiad to date), which were played through loudspeakers. Kevin and Bob McKenna’s Rues-miroirs involved a set of manipulated photographs placed on a large curved panel at street’s edge, occluding the empty lot behind it and demon- strating how the modern city street grid tends to mirror and replicate itself. Pierre Ayot and Denis Forcier’s La croix du Mont Royal sur la Rue Sherbrooke consisted of a replica of the massive Mount Royal Cross laid on its side on McGill University’s lower field, and was interpreted by some to be a political statement on the social and cultural hegemony of the Catholic Church in Quebec up until the Quiet Revolution.

Mémoire de la rue by Lucie Ruelland, Pierre Richard and Jean-Claude Marsan consisted of a series of photographs explaining the history of Montreal as told by referencing key locations along Sherbrooke Street. The work used orange hands—something of a synthesis of Mickey Mouse’s and the pointed index finger of the First World War “I Want You” poster—to identify these locations. According to a 2001 Canadian Art interview with Charney, the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, which was identified as a point of interest on the route, found the hands distasteful. Mémoire de la rue was among the first exhibits to be targeted for destruction on July 13. Some of the artists later suspected the real estate developers who had replaced the mansions of Montreal’s “Millionaires Row” with stunted steel and glass boxes felt that those fingers pointed at them: J’accuse!

Mémoire de la rue was complimented by another project entitled La légende des artistes, by Françoise Sullivan, David Moore and Jean-Serge Champagne. This work was composed of a dozen wooden boxes, each featuring objects and photo-assemblages detailing major Montreal cultural figures—artists, writers, philosophers and revolutionaries—mounted at eye-level and located within proximity of where these figures lived. These two projects were intended to spell out the connection between a city’s built environment and cultural heritage. And unlike many of the more artistic endeavours, these were also accessible to the general public. In the week or so that Corridart stood unmolested, crowds gathered to peer into their own city’s history.

Other components of Corridart were more whimsical in nature. For Cross-country, Yvon Cozic wrapped trees in vibrant colours and numbers, intended to give the impression of long- distance runners. Guy Montpetit developed Sculptures en série, six tall structures made of wood and covered with patterned, brightly-coloured nylon. Jean-Claude Thibaudeau contributed Molinari-inspired kites, and Charney himself provided Les maisons de la rue Sherbrooke, a movie-set building façade offering a mirror image of what stood across the street on Saint Urbain.

Together and apart, Corridart’s installations were intended to get people thinking about the city they lived in, about their shared culture and heritage. Rather than being a backdrop, Sherbrooke Street—the artery connecting old and new, rich and poor, official and ad hoc—was an integral contextual setting for understanding the forces that had shaped, and were shaping, modern Montreal.

The official reason given for Corridart’s destruction—public safety—does not appear to be the whole truth. All other answers are guesswork, but it seems that Corridart was destroyed for a simple reason: Drapeau didn’t like it, and, well, he could. He likely calculated that Corridart’s destruction wouldn’t cost him much in the way of political points or important allies, and, at a time when Montreal’s bridges were being checked for explosives several times a day and armed fighter jets waited for hijacking alerts at the far end of civilian runways, he wagered the public wouldn’t be too upset if he played a heavy hand against a bunch of counterculture radicals.

On Sherbrooke Street that July night, as city workers razed the artwork, Melvin Charney and Corridart coordinator André Ménard were interviewed by the Montreal Gazette. Charney declared that Corridart’s destruction had happened without any warning or consultation from the city. “I’m stunned,” Ménard told the paper. “I’m basically in tears.”

IN NOVEMBER 1976, a dozen artists launched a lawsuit against the City of Montreal over the destruction, seeking $350,000 in damages. The decision, rendered five years later, affirmed Drapeau’s opinion: the judge called into question the aesthetic qualities of the exhibit and noted that too many installations cast Montreal in an unfavourable light. In a 2001 Canadian Art interview, Charney likened the situation to having a judge blame a rape victim for what they were wearing. The artists appealed the decision in 1982. Just as the appeal was about to be heard in 1988, the new mayor, Jean Doré, sought an out-of-court settlement of $85,000, which, after legal costs, left the dozen plaintiffs with a token sum of $3,000 each.

Drapeau remained publicly unrepentant over the Corridart incident until the day he died in 1999. The Montreal Olympics were estimated to have cost the city nearly $1.5 billion, a sum that took thirty years to pay off. The major Olympic installations—notably the stadium and tower—have suffered from various structural problems in the years since, requiring millions more in tax dollars for repairs. None of Drapeau’s promised East End urban development ever materialized, and to this day the Olympic Park stands out as a wholly alien construction with no relation to its surroundings, physically and aesthetically detached from its home city. Though the generally defective and ill-conceived Olympics buildings continue to cost Montreal, there’s little evidence that the city’s residents have derived much lasting use from them.

Drapeau’s Olympic vision may be best described as myopic, but its end result was prophetic. Despite the legacy of the Montreal Games, many subsequent host cities have essentially followed the same if you build it, they will come school of urban planning. Budgets have ballooned out of control, far out of proportion to realistic expected returns or post-Olympic usage.

Forty years later, Montreal has a new mayor, Denis Coderre, who shares Drapeau’s interest in sports-related mega-projects. The city is approving many new office and condominium towers of dubious value. It sells itself as an artistic and creative nerve centre, but loses spaces of creation to condos. Its neighbourhoods continue to be rebuilt and rebranded, all too often with superficial references to the area’s history.

And, just in time for the next iteration of sweeping public celebration (in this case, 2017 marks the 375th anniversary of the city’s founding) the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts and the McCord Museum have joined forces to propose a series of art- works along Sherbrooke Street. There are no plans to call the project Corridart 2.0.

MELVIN CHARNEY DIED IN SEPTEMBER OF 2012, leaving two distinct marks on his hometown: the Canadian Centre for Architecture's interpretive garden, and the sculpture Skyscraper, Waterfall, Brooks — A Construction, which was commissioned for the city’s 350th anniversary in 1992. The former is one of Montreal’s best kept secrets: a scenic refuge in the middle of the city’s most densely populated neighbourhood whose architectural, sculptural and landscape elements communicate key elements of Montreal’s physical character and history. Both these projects were realized after Jean Drapeau had retired.

According to Ann Charney, her husband and Jean Drapeau met face to face only once, many years after the Corridart affair. They bumped into each other at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. Charney looked Drapeau in the eye and said they had met once before, in another corridor of art. Both men then turned and walked away.