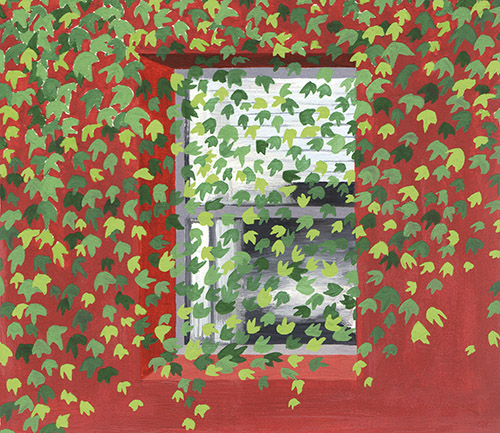

Art by Caitlin McGuire.

Art by Caitlin McGuire.

Behind Closed Doors

Everyone needs fresh air, but Canadian psychiatric patients can go years without stepping outside.

At 7:15 AM, I’d tap my ID badge against a keypad and step onto the general ward of the inpatient psychiatry service, careful that the door locked behind me. Looping the lanyard around my neck, I would wade into a smell of damp toast and disinfectant. The nursing station was a plexiglass pod at the centre of three units of varying degrees of security, each separated by another set of locked doors. In the early morning, before the hallway lights came on and the flurry of shift change began, the nursing station glowed like an aquarium.

There was one elderly man who, for the three months he spent in the downtown Toronto hospital where I worked, followed the same routine. Each morning, he woke with the urgency of a person late for a very important meeting. On the security screen we’d see his slight frame dart about his room, his woolly sweater with professorial elbow pads, his hair a little rumpled from the night’s sleep. Invariably, he tucked a book under one arm and, under the other, bundled as many markers, papers and paintbrushes as he could clutch. Briskly, he’d set off down the hallway until he reached a locked door. Then he would turn and walk the other direction, arriving at the same result.

Noticing a nurse, he would wave through the plexiglass window with a mixture of patience and panic. The consummate professional, containing his frazzle, he’d ask, “Where am I going?” We would let him know that this was the only place he needed to be, reassure him breakfast would soon arrive and show him his room, the lounge, the hallway: the three places a person on an acute mental health unit can go. He accepted this orientation politely most every morning, like the time loop of the film Groundhog Day. Sometimes, as we returned to the nursing station, he’d give us a paternal pat on the shoulder and tell us we were “such good students,” his eyes twinkling with pride. “Remember your Canalettos!” he’d call out, as though he were bidding us a final farewell after a summer art course abroad.

Eventually, his psychiatrist sympathetically brokered supervised visits to the general ward, where he could play the piano or walk in the hospital’s cement courtyard. This was special treatment—most patients don’t get that. His visitors or staff, including me, would accompany him.

I remember walking him around the small concrete yard, where he would look up to the sky. He became animated, talking with authority about things he knew, like how Edinburgh is built among hills that grant dramatic views of stone buildings and spires. His thoughts sometimes led to dead ends, but he would return to the acute unit peaceful. He started telling nurses and his psychiatrist that there really ought to be some greenery in the courtyard. He was incredulous that it was so bare of life, even drawing sketches for a green design for it. “Wouldn’t this be better?” he asked.

I thought about him even after he died in 2013, a year or so after he left our unit. Nearly every patient I’d ever worked with asked to go outside, but his requests seemed particularly tragic.

Among the books he carried around was one he’d written—at least he recognized his name printed on the cover. Although he couldn’t explain his ideas any more, he knew they were important. “This, this,” he would say, pointing at the cover. “Do you know it?” His book described the inextricable connection between humans and nature, and the importance of building in harmony with the environment—for example, the way Edinburgh takes advantage of an undulating landscape instead of struggling against it. He had committed all his working years to bringing nature into human architecture, until, at the end of his life, he was cut off from it himself.

I have worked as a nurse for a decade, mostly in Toronto and, until a year ago, mostly in mental health. I like existential explorations and unusual points of view, and I learned a lot from patients.

One evening nearly seven years ago, from behind the shatterproof panes that surrounded our station, a patient knocked and I slid open the window between us. He looked determinedly down at his hands and counted what he believed to be his rights. “One shower, one change of clothes, one hour of fresh air,” he said. “As a prisoner, that is what I am entitled to.”

He had been a prisoner before, but that wasn’t his designation here—I was his nurse, not his warden. “You are welcome to all the showers and changes of clothes you would like,” I answered, “but I can’t let you outside.”

Of the many causes for concern in mental health care, outdoor access was not an issue to which I had given much thought until that moment. But suddenly, after giving this same answer to patients for two years, it seemed very strange: patients couldn’t go outside.

“You hear patients say it all the time: ‘This is worse than jail,’” said a former colleague of mine, Kristy Colasante, who spent five years as a psychiatric nurse. The longer I worked in mental health and the more units I saw as a nursing instructor, the more uneasy I became about the way we confine patients indoors.

Last year, I worked my final shift in inpatient psychiatry. I remember glancing at the upper-right-hand corner of the electronic medical record belonging to one of my patients, where a little box showed length of admission. It was 1,117 days.

The only exposure this person has had to the world outside in more than three years, I thought, is through a window—advertisements flashing across screens in a square, shoppers scuttling about like insects on the street seventeen floors below.

For reference, the maximum sentence that can be served at provincial and territorial prisons across Canada is two years less a day. And even in an Ontario prison, as I was starting to learn, an inmate can expect to go outside for an hour a day.

“Confining someone is the most serious thing that we do to people in Canada. We don’t kill them anymore, but we do confine people to small spaces. This is the worst punishment that we can devise,” says Jennifer Chambers, the director of a patients’ advocacy council at Toronto’s Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. “And yet we do it to people who are simply in a distressed state of mind.”

Health professionals don’t take this lightly, either. Dr. Thomas Ungar, chief of psychiatry at Toronto’s St. Michael’s Hospital, often tells young doctors-in-training that their “greatest privilege and power… is not the ability to prescribe or do surgery,” he says. It is “to temporarily suspend someone’s civil liberties through the Mental Health Act.”

There are two ways patients on mental health units come through the door: involuntarily and voluntarily. Involuntary patients are admitted under the power of mental health legislation that temporarily suspends the right to leave the confines of the hospital. Voluntary patients retain their civil rights and can leave, at least in theory.

In practice, it’s never as simple as what’s on paper. For voluntary patients, if a doctor isn’t confident a person will safely return to hospital, he or she must stay inside until staff feels comfortable letting him or her out. If patients disagree, their only recourse is to sign themselves out of hospital, against doctor’s orders, effectively foregoing treatment. Hospital staff’s worries are real and warranted; patients have died by suicide on passes. Still, this is not a choice for patients in the true spirit of the word.

But the bigger problem, for all mental health inpatients, is the problem of architecture. Whether or not a patient gets fresh air depends entirely on the design of the hospital unit where they’re treated. Ontario does not require hospitals to have secure outdoor space, even for the seventy of them designated to admit mental health patients against their will into locked units. It’s unclear how many facilities happen to have this space anyway, across Ontario and across Canada. Ontario’s health ministry told Maisonneuve that it does not require hospitals to report whether they have outdoor space for patients.

But those who work in the field say it’s rare for psychiatric hospitals and psychiatric hospital units to have a secure yard of some sort, especially those housed in general hospitals. The majority in Ontario have none, says Chambers, based on her own experience. Of the seventy hospitals in the province that treat involuntary patients, thirteen are in Toronto, and of these, I have been inside seven. None of those has outdoor access for its acute unit, where most patients are admitted involuntarily. And in the two where outdoor space does exist, for the general ward, the quality of that space is dismal: one is a walled-in, concrete slab under a ventilation system that spits condensation onto visitors; the other is a balcony enclosed top to bottom by chain-link fencing.

In other words, no one set out to trap psychiatric patients indoors. Yet we do. Getting inpatient mental health treatment often comes at the terrible and unhealthy price of losing fresh air.

Last year, I called the wife of the man I had known on that unit, the man I’d never forgotten. Soon after, I met Bridget Hough, a vital eighty-three-year-old dressed smartly in a button-up shirt and slacks, at her apartment. She didn’t remember me from the hospital; that was seven years ago. After inviting me in, she led me down a hallway. “I have something to show you,” she said.

Venetian blinds sliced up a view of Toronto parkland, knocking together in a breeze as we entered a room, its walls tiled with framed artwork. She gestured to one watercolour showing a cobblestone street stretching out to a cloudless horizon, flanked by balconies overflowing with flowers. “Guess who did it?” she asked. “He couldn’t stay still,” Hough added. “He did that in 1956 on the Costa Brava, where we’d honeymooned.”

Bridget grew up in a small town in the Yorkshire Dales surrounded by farmland and moors. “We climbed the fells and trees, paddled and swam in the rivers, went for hikes over hill and dale, cycled for miles along country lanes,” she said. “I took it all completely for granted.”

Shortly after starting a course at the Edinburgh College of Art, she met her husband, Michael Hough. The couple soon embraced North America’s wide-open wilderness: Michael’s ambition was to pursue graduate studies in landscape architecture, which took them first to the United States and ultimately north. Together they explored the wild spaces of state parks and learned to canoe on Lake Champlain from an American activist, who inspired them with the story of how she’d successfully campaigned to save a wetland from the planned expansion of the Philadelphia airport.

Michael’s own dedication to environmentalism transcended his intellectual interests. Bridget described his drive as “prodigious,” speculating that it originated in an isolated childhood and a desire to live up to the standards of his Cambridge-educated, multilinguist father who worked in Palestine for the British Foreign Service.

While his parents lived abroad, Michael had attended boarding school in the countryside of the home counties outside of London, England. “His school was beside a river, and there were wild spaces around there where he used to escape,” Hough says. “He became an avid bird-watcher and could recognize all the British birds and identify them by their song.”

They eventually landed in Toronto, where Bridget became a medical illustrator and where Michael founded the University of Toronto’s landscape architecture program and later taught environmental studies at York University. They had three kids, a home in the city and a cottage near Parry Sound set in two hundred acres of woods. On weekends, their whole family would go for ravine walks, and up at their cottage the children would explore freely—their daughter became a professional wilderness guide.

In their adopted city, their children attended school on the edge of one of Toronto’s ravines, and soon, the young couple joined a parent group to campaign for those lands to be used as an outdoor classroom. Michael worked to help preserve Toronto’s Don River, an effort that culminated in a well-loved park around a former brick factory, called the Brick Works, which is now home to social enterprises and a weekly farmers’ market. He became an award-winning landscape architect, designing, among other projects, the iconic waterfront Toronto landmark Ontario Place. “He would have been thrilled,” says Bridget, “to see that it has now, fifty years later, grown into an urban forest.”

Michael’s books are now required reading for students of landscape architecture and urban planning in Canada and abroad. Toronto’s former chief city planner, Jennifer Keesmaat, tweeted in 2017 that the report he authored on naturalizing the Don River “seemed crazy in 1990,” but, twenty-seven years later, his idea was funded with $1.4 billion, after “very slowly… gaining traction as a best practice.”

Michael’s design philosophy even reached the psychiatric hospital on Toronto’s Queen Street West—what we now know as the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health or CAMH. In the early 1960s, when the Victorian buildings began to come down to make way for modern construction, his firm was chosen to reimagine the twenty-seven acres of the former walled asylum. The new design opened the grounds, like a park, to Queen Street. Paths wended through the green space, between buildings, giving staff and outpatients a glimpse of nature on their way to appointments, even though the involuntary inpatients would only have viewed the grounds from windows. Michael built a terrace in his home garden with bricks salvaged from a wall built by asylum patients—the wall his renovations had brought down.

This work would echo in the Houghs’ own lives sooner than they imagined. In 1984, Bridget was recruited to produce an educational video for U of T’s medical school about schizophrenia. She began to notice that one of her sons was displaying many of the signs she was learning about. He had been a solitary soul, even in childhood, and like his father, found refuge in bird-watching and in making art. He had just finished art college when he was diagnosed with schizophrenia and admitted to a downtown hospital’s psychiatric unit.

Bridget confronted her son’s illness head-on. She phoned his boss at Ontario Place, where he was employed as an artist drawing bobble-headed caricatures, to explain his absence. “I didn’t say ‘he’s not well,’ I said, ‘he’s on the psych ward,’” she recalls. “I didn’t pull any punches.” Her son’s boss acknowledged he’d suspected something was going on and said to tell him that when he was feeling better, even if he could only put in a few hours a day, he could come back. “I think that was amazing for that era,” says Bridget, shaking her head in disbelief.

The month Bridget’s son spent on the psych ward is distant in her memory. But she is very clear about one thing that helped him recover: the encouragement to get straight back to work and out into the world while still staying overnight in the hospital, where he had the support of experts. By the end of the summer he was back to working full-time, drawing en plein air. “He had that job every summer for the next nine years,” she says.

Bridget’s son is a success story. He lives independently and his paintings, depicting animals and landscapes with autumnal oils in the style of high realism, have spread across pages of Canadian art magazine Arabella. They also hang on his mother’s bedroom wall.

In 1984, the same year the Houghs’ son spent the summer in hospital, a professor of architecture named Roger S. Ulrich published a groundbreaking study of patients recovering from gallbladder removal in a suburban Pennsylvania hospital. He wanted to test whether exposure to nature had an effect on their recovery. Aided by the layout of the hospital unit, Ulrich was able to randomize the participants—half the patients’ rooms faced trees and the other half faced a brick wall.

That in itself is a rare accomplishment. The benefits of nature to mental health have been widely researched, but very few studies have been designed to meet the rigorous gold standard for medical research, the randomized control trial. And the bulk of attention has been trained on depression and anxiety; psychotic disorders are grossly under-examined when it comes to this question, even though this subpopulation is more likely to require inpatient hospitalization.

But understanding more about the role of nature in psychiatry could save both suffering and money. Unsurprisingly, in Ulrich’s study, the patients with tree views had shorter hospital stays, fewer doses of pain and anxiety medications and slightly lower scores for minor postsurgical complications. His findings showed that exposure to nature made the gallbladder patients healthier and less expensive to treat.

Imagine if the same patterns were shown to hold true for mental health treatment, and were taken seriously; time spent outdoors could possibly save costs on anti-anxiety medications and sleeping pills. A key component of recovery from psychosis or a mental health crisis is quality sleep and routine, and sunlight is vital for regulating both the circadian rhythm and mood. Sun exposure produces serotonin, a neurotransmitter that can affect positive mood and optimism; in darkness, serotonin is converted to melatonin, a neurotransmitter-like hormone that regulates sleep.

Treating mental illness in general hospitals at all is a relatively new practice; it began about seventy years ago, when provincial asylums were collapsed into local hospitals. And the convention of hermetically sealing hospitals from the outdoors is just as recent.

Before the 1870s, a hospital was a very airy space for the purpose of infection control. Miasma theory, the belief that bad air was the cause and carrier of illness, was the dominant idea of disease transmission. This belief was corroborated by meticulous morbidity and mortality statistics collected by the iconic lamp-wielding nurse Florence Nightingale during the Crimean War. Nightingale championed a “pavilion-ward plan” for hospitals, which meant well-ventilated, small-scale buildings that allowed the circulation of outside air and welcomed sunlight. Hers were the first evidence-based designs and remained the international standard for Western hospitals for over one hundred years.

For a brief period coinciding with Nightingale, fresh air and sunlight were also considered key to mental health care. Psychiatrist and asylum reformer Thomas Story Kirkbride promoted a brand of “environmental determinism” professing that architecture could shape behaviour and encourage a “regimented life,” ultimately curing mental illness. A great deal of support was put behind Kirkbride’s therapeutic blueprint, which was guided by principles of a healthy diet, exercise, occupational tasks like farming, carpentry or laundry and the freedom to stroll the grounds. In the span of his career, between 1840 and 1880, the number of asylums in the US jumped from eighteen to 139.

The way people imagined a healthy space was drastically transformed by the germ theory of disease transmission that gained wide acceptance towards the end of the nineteenth century. New, aseptic design principles required hospital spaces to be absolutely sealed from one another to keep germs from passing between them. Concurrent advancements in construction and engineering like plumbing, mechanical ventilation, electricity and the Otis elevator made it possible for hospital architects to build skywards, offsetting land costs in urban centres and allowing separate departments to share new, expensive, unwieldy medical equipment like X-ray machines.

The rush of scientific and technological innovation in the early twentieth century made its mark in psychiatry, too. The field adopted an increasingly biomedical approach. From World War II onwards, the development of anti-depressant and anti-psychotic drugs stirred so much hope that British psychiatrist William Sargant boldly proclaimed mental illness would be eliminated by the year 2000.

It was a timely moment to believe that asylums would soon be obsolete. In the post-war period, they had become notoriously overcrowded and were sites of well-documented abuses. In Ontario, by the 1950s, asylums were filled to 170 percent of their intended occupancy. As the promise of the chemical revolution grew, a vocal anti-psychiatry movement gained momentum through the 1960s and 1970s. It rejected the idea that mental illness was an “objective behavioral or biochemical reality,” but was, instead, “a negative label for a strategy for coping in a mad world,” according to British medical historian Roy Porter. Critiques from patients were bolstered by psychiatrists and psychologists who rejected their discipline’s “oppressive demands for compliance and a sameness of human experience,” writes historian Carla Yanni.

Into the seventies and eighties, such pressures from the political left dovetailed with interests from the radical right, with both sides pushing for deinstitutionalization. Politicians like Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher, eager to decrease spending on expensive state-funded psychiatric hospitals, put their support behind “community care.” In Canada, between 1960 and 1975, thirty-five thousand beds in psychiatric hospitals were closed, while only five thousand psychiatric beds were opened in general hospitals.

This “lack of synchronicity”—closing beds without nearly enough community mental health services in place—created many problems, experts now say. Australian psychiatrists Paul Sullivan and Danny Mullen, for example, resist the term “deinstitutionalization” altogether. Rather, they refer to this movement as “transinstitutionalisation,” as “it moves the problem of mental disorder elsewhere—private homes, hostels, prisons, the streets—and benefits only the government, which no longer needs to fund these expensive services.”

Today, many mental health patients in Canada tend to cycle in and out of hospitals, staying nearly twenty-four days at a time on average, according to the Canadian Institute for Health Information. Between 2003 and 2004—the most recent data tracking patients for more than a month after their discharges from hospital—37 percent of people treated for a mental disorder across the country were readmitted within one year.

People who work in mental health sometimes wax nostalgic for the era of the asylum, a system none of us has known firsthand, but one that seems more humane—a place with grounds and meaningful activities, instead of a hospital where exasperated staff sometimes remind patients who have gotten a little too comfortable, “This is not a hotel!”

Bridget would come to see her husband’s work in a new light yet again. “I realized very early on what was happening with him,” she says. “I’d been putting these little bits of paper into all his pockets with my name and cellphone number,” she recalls of the period in 2005 when his dementia became clear. “He would find them and throw them away. We can laugh now, but it was so difficult.”

The week before Michael was hospitalized, he went out and got lost. It was January, and a stranger called Bridget, telling her that Michael had been walking up and down the unfamiliar street and had knocked on her door, handing her her mail.

One of Alzheimer’s most representative features is wandering. But, as recorded by pastoral theologian Donald Capps, the action of wandering with dementia is utterly disconnected from the notion of destination. “Purposiveness without purpose, directedness without direction, need without want—these are the hallmarks.” Capps considered wandering as a metaphor for the devastating disconnection of neural pathways that occurs in dementia—an action snipped from its intent, motivation or reason.

Bridget got advice for managing her husband at home: “Put your phone beside your bed, keep the door locked… if you’re really, really scared, phone 911,” she was told. The night she called 911, Bridget had to slip downstairs to open the door for police. “They sort of guided him into the living room and got him to play the piano,” she says, before they coaxed him into the cruiser. That night, Michael was checked into the same inpatient psychiatric unit where their son had been admitted decades earlier.

These days, the hospital experience is increasingly the experience of those with dementia. “The reality is, with an aging population, there are people living in hospitals for years and years and years,” says Colasante, my former colleague. People with dementia are often held involuntarily in acute units because they need so much care. Many never go outside for the last several years of their lives.

This is still worse for anyone whose mental illness has disrupted their relationships, including many with psychosis—people who don’t have partners, parents or friends who show up to take them out.

In 2016, Ontario’s Auditor General found that one in ten patients in specialty psychiatric hospitals was ready for discharge but, because of the dearth of supportive housing and long-term care beds, had nowhere to go. The problem had worsened over the last five years, the report said. General hospitals face the same barriers; social workers require Herculean tenacity to find long-term care for clients with dementia or a mental health history, especially those who have been violent.

For a nurse, over time, the repetitive demands to step outside for air or a cigarette begin to sound not like sincere and reasonable requests but tests of your equanimity. But it’s not just nurses who experience this sort of fatigue. In 2004, Chambers and her patient advocacy group were part of a push to encode outdoor access in a Bill of Client Rights for CAMH, an organization that serves thirty-four thousand people a year. Even in drafting this aspirational document, Chambers had to fight to include outdoor access on a wish list for voluntary patients. “People would say, ‘Well, we can’t always do it, sometimes there are security concerns, there aren’t enough staff,’” she says.

This is one symptom of what Chambers calls “organizational malaise.” People in the patient role can come to be seen, Chambers says, “as not fully human with all the needs that other humans have, like the need for fresh air and exercise and the ability to escape small crowded environments full of strangers.”

Voluntary patients have told Chambers that staff told them they can’t go out. “Staff use all sorts of coercion to prevent it,” Chambers said. Colasante acknowledges that access to the outdoors is used as leverage in bargaining with patients. “It’s ‘if you take your medication, you can have a pass.’”

There is a bigger invisibility to this mundane cruelty as well. The United Nations Special Rapporteur on torture and punishment noted in 2013 “that there can be no therapeutic justification for the prolonged use of restraints.” But confinement is distinct from restraints in the terminology of Ontario’s Mental Health Act. “Restraint” refers to a mechanical or chemical means to inhibit a person’s behaviour or movement—mechanical, like binding a person’s wrists and ankles to a bed, or chemical, like administering a psychotropic medication. Restraints are openly debated in health care, while confinement does not inspire similar controversy. Confinement has been viewed by the medical community as an inconvenient necessity of treatment rather than a deprivation of freedom.

Another problem is one most of us understand too well. The stigma of mental illness is, even for advocates, heavy to bear, despite how many want to speak publicly about this predicament. One mental health proponent I know is a sixty-one-year-old woman who describes herself as “determined to live a healthy and adventurous life.” She was eager to talk about her confinement during the three or so hospitalizations she’s endured, but she asked to remain anonymous, describing her time on a locked unit as “a feeling of being punished.”

Don’t mistake how little you hear about this issue for how much patients care about it. Their will to get fresh air can be ferocious, expressed with screams and fists pounding upon the partition between staff and patients. Only after months of denial is that will, in some cases, defeated.

One irony is that the patients who are more intentionally confined—those who have committed crimes and are being treated at forensic hospitals after being found not criminally responsible—generally get better outdoor access than other patients. Don (not his real name) has lived in a forensic hospital in Kingston, Ontario, for a year and a half, since, in a moment of emotional distress, he attacked his father and badly injured him. He was found not criminally responsible and sent from his home in Sault Ste. Marie to Kingston to be treated.

This is not the first mental health setting Don has been in, but it’s the first that’s forensic—and the only one where he’s had significant access to outdoor space. Don says he’s permitted to go out between meal times under the supervision of a nurse. The yard has enough room to walk around, play basketball or throw a football.

Psychiatry isn’t just about medicine. It has an inherent ethical tension: public safety versus personal liberty. No one understands that tension better than Justice Richard Schneider, the chair of the Ontario Review Board, the quasi-judiciary body that manages forensic patients like Don who are found not criminally responsible due to a mental disorder. Justice Schneider says the challenge with every hearing is balancing the public’s protection, “which is the paramount concern, and the rehabilitation and other needs of the accused.” He says, “We don’t want to restrict anyone a minute longer or an inch further than what is required.”

The United Nations Declaration of Human Rights doesn’t say people have a right to fresh air, and neither does the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. In fact, the only guidance on this I could find had to do with prisoners; the Mandela Rules, for instance, the UN’s standard on the treatment of prisoners, say inmates ought to be permitted a minimum of one hour of outdoor access a day.

Across Canada, three provinces have encoded outdoor access for prisoners—Nova Scotia, Alberta and British Columbia—and Ontario committed to doing the same in a legislative update last year. In Ontario’s provincial prisons and in all federal penitentiaries, current policy already says prisoners can expect to go outside.

Perhaps forensic patients like Don have gotten their architectural advantage because the forensic mental health system has its origins in the criminal system, where secure yards are customary. Until 1992, people found not criminally responsible in Canada were managed by the criminal system. In Ontario, many buildings dedicated to forensic psychiatric patients have secure yards, like prisons, despite having no formal requirement to do so.

Even at CAMH, the forensic unit has the best outdoor access, Chambers says, with its own fenced-in yard. None of the lower-security units for voluntary patients has a secure yard. During talks over another redevelopment around 2004, Chambers’ group brought up this inequity, asking why all patients couldn’t have a fenced-in yard. Hospital administration responded, “‘Well, it wouldn’t look good,’” Chambers recalls. They worried “it would make the place look too much like a prison.’”

Secure green space, however, could contribute to a safer, healthier experience for both staff and patients. Studies on the use of restraints have found that “what precedes someone being restrained is usually someone being loud and agitated, not violence,” says Chambers. “I’d be agitated too if I didn’t get fresh air and exercise.”

Don says his unit is pretty tense, with patients’ tempers strained by all the rules they’re asked to follow. His main solution is to go outside a lot, “keeping things moving” by walking around the yard and clearing his mind. I asked what would happen if the facility didn’t have a yard. “I think it would explode,” he said.

Oddly enough, in an era of increasing openness about mental health, access to green space has been getting worse, not better—at least in Canada, where a wave of lobbying hasn’t begun as it has in some US states.

Going outside was essential for mental health activist Jonathan Dosick’s own recovery when he was hospitalized on units in Massachusetts. “Whether it was the spring or the summer or the freezing cold, I always felt better when I came in—I felt more connected to the outside world. Being on a hospital unit can be like being on the moon,” he says.

But from Dosick’s first hospitalization in 1989 to his last in 2002, practices for passes became more restrictive. After learning from a doctor based at a Boston-area hospital that they were no longer letting people outside at all, Dosick took action. “Even the FDA has requirements for organic livestock to have outdoor space and fresh air,” he argued as he rallied support. In 2016, Massachusetts finally passed a bill that enshrined outdoor access for psychiatric patients.

Efforts to improve the situation in Ontario have been piecemeal. With few advocates working at the policy level like Chambers, it often falls to individual patients and their family and friends to seek solutions case by case. A Charter challenge might be the only way to force bigger change. The problem is that the patients most acutely affected by the problem are often those least equipped to organize something like a court case.

But one such patient did make it to court. In 2014, a man came before the Ontario Court of Appeal to argue that his Charter rights had been violated, as he had been detained at a psychiatric hospital for nineteen years. The court agreed, ruling that involuntary hospitalizations lasting more than six months are similar to criminal detentions. Yet the provincial review board responsible for overseeing civil mental health treatment—rather than forensic patients—lacked the jurisdiction to adequately address this, the court found. Now, if a person is held involuntarily for more than six months, that board is invested with powers to order changes for patients, like a transfer to a lower-security facility. Legal scholars Isabel Grant and Peter Carver argue this decision should trigger an analysis of civil review processes for all provinces and territories.

Still, without architectural changes, this review board or any other governing body will come up against the same limitations that hospital staff hit. Making these architectural changes obligatory, Dr. Ungar says, is a vital solution. “If you put certain structures or requirements [in place], it’ll happen,” he says.

Furthermore, for people hospitalized involuntarily for less than six months, this ruling has no bearing. “I think the amendment to the legislation is a very positive one,” says Justice Schneider. “My only comment would be that it doesn’t matter whether it’s six months or six hours or six minutes—any time the state steps in to limit someone’s liberty because of the risk they pose to themselves or to others, it should never exceed what is required to mitigate the risk.”

Long-term care homes, unlike hospitals, have advanced policy in this area that applies to all future buildings. A 2015 update to the design manual for long-term care facilities introduced a requirement for one enclosed ground-level outdoor space for new builds.

CAMH is currently in the midst of a high-profile redevelopment of the Queen Street West campus. In the sixties and seventies, most of it stone walls were broken down, but the current renovation promises to integrate the institution more closely into the local neighbourhood with a goal of further destigmatizing mental health.

But CAMH also wants a return to greenery. In a statement, the hospital said that by mid-2020, all inpatient units will have access to “therapeutic outdoor areas,” though it didn’t provide the dimensions. It also took care to plan for more working windows and said that in two new buildings, the layout will give all bedrooms a view of gardens and green spaces. “CAMH believes that patient access to fresh air and outdoor activity plays a pivotal role in enhancing healing and recovery,” a spokesman said.

While Michael was living on the acute unit, Bridget persistently searched for a long-term nursing home for him that had outdoor space. It takes an average of three months to find a bed in long-term care for a patient in hospital, and Bridget, with the help of a hospital social worker, managed just that.

His new home was a facility in Scarborough run by a church-affiliated foundation. She told me that there, too, the staff learned the best thing to do when Michael’s confusion made him agitated—bring him outdoors. “One of the tricks they used was to take him down to the courtyard, which was full of trees, shrubs and flowers, and a fountain,” she says. “But of course, staffing levels are such that they couldn’t always spare the time.”

At the end of her twice-weekly visits, Bridget would try to time her exit so that her husband and other residents wouldn’t notice. Otherwise, they would try to storm the door to escape. “I remember one particular woman who had a walker,” Bridget says. She used “it as a battering ram on the doors, every opportunity she had.” Bridget had become familiar with this disturbing scene, common in hospitals and long-term care. It is “a result of the disease,” she says. “The person doesn’t understand why he is being kept inside.”

As Michael became more frail, unable even to manage these outings, his family supplied him with the BBC Earth series, knowing that following the camera as it panned over expanses of wild land would soothe him. Eventually, someone had to put them in the VCR, because he could no longer manage that. But he kept watching them, over and over again.

TORONTO'S LOST HEALING GROUNDS by Peter Kuitenbrouwer

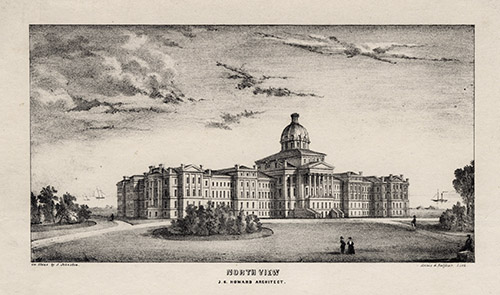

An 1849 lithograph of Toronto’s Provincial Lunatic Asylum, from Queen St. opposite Ossington Ave., with a view towards the lake.

An 1849 lithograph of Toronto’s Provincial Lunatic Asylum, from Queen St. opposite Ossington Ave., with a view towards the lake.

It wasn’t so long ago that doctors believed green space could cure mental illness, and they had city planning to match. In 1850, along the south side of Toronto’s Queen Street West, a three-metre yellow brick wall stretched for ten city blocks, from present-day Trinity Bellwoods Park to the train tracks at Dufferin Street. Behind the wall rose the Provincial Lunatic Asylum, the crown jewel of psychiatric hospitals in Ontario.

The Classic Revival palace looked out on fifty acres of lawns, fountains, flower beds and fruit and vegetable gardens. There were stables and barns, hay and grain fields. Birds flitted in a long row of fruit and shade trees just inside the wall.

“Lunatic asylum” is a judgmental label we would never use today, but for the place’s founders, “this was not a place of incarceration; it was instead the embodiment of a powerful and humane value system,” writes historian Alec Keefer in The Provincial Asylum in Toronto. Its architect, John George Howard, visited American sites like the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane, whose designers believed restoring patients’ mental health required interaction with nature.

At the Toronto asylum, patients could go for walks under the shade of trees or play lawn bowling and cricket, not to mention grow prodigious quantities of food, including clover, hay, oats and timothy for the horses and cattle. In 1889, for example, the patients gathered 4,850 bunches of asparagus and 490 bushels of tomatoes. This produce made the hospital largely self-sustaining in food; more importantly, the gardens offered patients fresh air and exercise. In 1889, the Mimico Lunatic Asylum opened further west along the shore of Lake Ontario. Architects designed that hospital as a series of cottages in red brick with a cheerful, home-like appearance; staff escorted patients on daily walks.

The belief that nature is axiomatic to health goes back to the gardens of Babylon; in Europe, monasteries were the hospitals of the Middle Ages, and they had ample green space. During World War II, when the Canadian government began designing a new Toronto hospital for wounded veterans, it wanted a pastoral setting. Sunnybrook Hospital opened in 1948, surrounded by forests. Here, too, patients grew their food.

Marian Lorenz, who worked in Sunnybrook administration for fifty years, believed that “for any patient, it was psychologically uplifting to be able to look out the window and see trees and beautiful surroundings, as opposed to concrete and cement.” Lorenz feels the natural setting played a “key role” in helping the soldiers heal, but especially “those patients who had fractured minds as opposed to fractured bodies.” Researchers have confirmed in recent decades that patients who spend time in forests and parks see reduced blood pressure, improvements in mood and strengthened immune systems.

Portions of the yellow brick wall are the only remnants of the Queen West facility that remain today. The wall meant staff could let patients stay outside for long periods without fear they would flee. Today we would perhaps describe the barrier, which the patients themselves built, as cruel; as early as 1906, a report decried the “gaol-like walls.” Dr. David S. Goldbloom, a professor of psychiatry at the University of Toronto, said “the noble reason” for the wall was giving patients fresh air. “The less noble reason was ‘Out of sight, out of mind.’”

Two changes came in the 1950s. First, the widespread introduction of psychiatric drugs allowed more patients to live in the community. And, more importantly when it came to city planning, most hospital staff purchased cars, so the downtown asylum, then rebaptized the Queen Street Mental Health Centre, eventually paved over its lawns, gardens and orchards for parking. Sunnybrook Hospital, too, paved over huge stretches of green space and gardens, and now offers parking for 4,500 cars instead.

On Queen Street, by 1975, the stigma around the building had become so strong that demolition crews knocked down Howard’s palace. The replacement: squat cruciform towers in poured concrete and glass—with locked doors. The era of the therapeutic landscape cure was over.