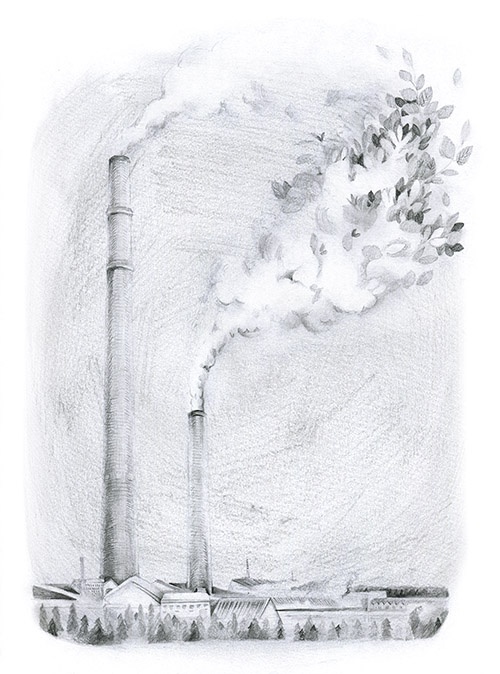

Illustration by Mathilde Cinq-Mars.

Illustration by Mathilde Cinq-Mars.

Mine Reading

Reckoning with a homegrown hell showed that turning around emissions can also mean turning a profit.

Coming off a shift at the smelter in Sudbury, at one time, a worker might step outside in broad daylight and ask himself, “Where in the hell is my house?”

Hell is the appropriate word, because he would be surrounded by thick sulphur smoke, the stuff of brimstone. The plant he’d just left, where ore was fed into a blast furnace, coated everything in this smoke. When the clouds were low and the air damp, instead of floating off, the sulphur haze would sit even lower than the clouds, clinging to the ground. On days like that, one side of the street would not be visible from the other.

But the workers had a system. Once the whistle blew for the end of shift, the wives of the men at the plant would step outside their front doors to shout the name of their husband to guide him home. A small town of personal sirens, calling the men not towards a rocky shore on a violent sea, but out of the acrid smoke they made for a living.

This smoke didn’t just make it hard to find your house; it stripped the land bare. For miles around, the landscape was barren wasteland, the trees, shrubs, grass all choked to death. Decades of mining and smelting had made a place once called Ste. Anne of the Pines mostly treeless.

That was less than fifty years ago. Today, sulphur smoke no longer hangs over the city, no matter how low the clouds or damp the air. And on clear days, when you can see for miles, the vista is no longer an endless nothing; Sudbury is green. In many ways, the city has turned itself around in a single generation. It’s a remarkable story of environmental renewal.

These days, hearing about such victories can almost feel discouraging. It’s a reminder that emissions crackdowns were once possible—while now, facing the most dangerous one of all, CO2, governments seesaw and it’s hard to see how industry will tackle the problem in time.

But Sudbury’s story should be comforting, and more than that, it could be a blueprint. The truth is that it wasn’t just public pressure or even politicians’ will that fixed the city’s environmental problems. Nor did a green, technological revolution debilitate the local mining industry. Instead, the mining companies saved money, and the technology paid for itself. The corporate world invented what it needed for the change, with government sometimes even following its lead. Sudbury shows that industry not only has more power than we realize to take the reins, but also more motivation.

The International Nickel Company, known better as Inco, was once so entwined in the fabric of Sudbury that its name was immortalized by Stompin’ Tom Connors. “Yeah, the girls are out to bingo/And the boys are gettin’ stinko/And we think no more of Inco/On a Sudbury Saturday night,” he sang in the chorus of the 1967 hit “Sudbury Saturday Night.”

That Sudbury would turn into a rough-and-tumble mining town was as inevitable as gravity. The city finds itself on the edge of a crater formed when a meteor, believed to be up to ten kilometres across, slammed into Earth some 1.8 billion years ago. The depth of the crater formed by the impact may have been as deep as fifteen kilometres, and its diameter was about 250 kilometres. It’s still one of the largest impact craters in the world.

The land around is Canadian Shield: metamorphic rock jutting through thin soil. Picture the sparse but hardy landscape popularized by the likes of Tom Thomson, with spindly pines clinging to barren rock scarred by lakes and rivers. It’s the sort of vista that looks windswept even on a breezeless day.

Scientists believe the impact of the meteor, combined with the meeting of several geologies and fault systems, created massive mineral deposits in one area. In his book on the geographic history of the region, Oiva W. Saarinen describes how, in 1883, a group of workers clearing woods for Canada’s new railway first discovered a rusty-looking rock. Prospectors and speculators moved in, slowly locating the vast wealth locked underground.

But before the ore discovery, Sudbury’s land had already been damaged. Between logging and clearcutting for the railway, the huge and ancient pines had disappeared, replaced with smaller trees like birch. That eroded soil and undergrowth. In a domino-like sequence, the bare landscape was particularly vulnerable to fire—accidental blazes, then prospectors clearing land by fire.

The ores, primarily copper and nickel, didn’t start a rush to the region. Freeing the metals takes immense amounts of heat and time. What was required in the region was heavy industry. And so began the most infamous stripping of the Sudbury landscape.

After the ore has been extracted, it undergoes a step called roasting. Essentially, the sulphur it contains needs to be burned off. Starting in the late 1880s, this began in earnest in huge open-air pits called roasting beds. The ground would be levelled out and stacks of wood piled on it in rectangles. Large chunks of ore would be placed on the wood, followed by a layer of ore powder to prevent open flames. When completed, the roast piles were about four metres high.

The wood underneath the pile would then be set alight. Once the ore reached roasting temperature, the heat would become self-sustaining and the ore left to roast for as long as seven months, until it burned itself out. More than 150 of these beds were scattered across eleven locations—spots that “took minimal account for factors such as the direction of prevailing winds, the impact on surrounding agricultural and forested lands, and plant life,” Saarinen wrote, not to mention their effect on humans.

It’s estimated that over the forty years the roasting yards were in service, they released ten million tons of sulphur dioxide. Clouds of SO2 stunted trees and shrubs. The soil was poisoned with particulates of heavy metals like nickel and copper. Local rocks began to blacken.

Farmers faced the brunt of the impact, their crops ruined. “Any man…could not help smelling the odour of dying vegetation, and on the following day the fields were a rusty dying colour, instead of a living green,” one farmer wrote in 1915. Farmers won compensation from one company but eventually lost a trial court case—a signal that mass industrialization was the national priority.

The march toward higher production continued, especially with the First World War. Companies moved to Crown lands, which the province then declared off-limits for settlement. In 1918, Ontario allowed companies to buy so-called “smoke easements” for the right to poison the air over landowners’ properties, even if the land changed hands.

Still, the damage was fairly localized, as the smoke from the roasting yards would only travel so far. In the late 1920s, the introduction of large-scale smelters and tall smokestacks would change that. Sulphur dioxide, when released into the atmosphere, cools, then reacts with the air to produce sulphuric acid. This creates acid rain. A 1945 report said it was possible to smell the sulphuric emissions as far off as sixty-four kilometres, and tree foliage was damaged. A 1967 government report put it succinctly: “One characteristic feature of the immediate Sudbury area is its apparent endless barrenness.”

Mining and smelting also produces large amounts of waste, especially tailings—essentially rock from which the metals have been removed, often mixed with water to make an easily transportable slurry. Tailings were piled and pumped behind huge dams, some as high as fifty metres. They covered a huge area; a few years ago, the Copper Cliff smelter alone had some twenty-two square kilometres of tailings, comprising about 10 percent of Canada’s total. Because these deposits were so large and so tall, wind would pick up their dust and blow it around.

But this moment, in fact, was an early indication that Sudbury’s downfall—the mining riches—could also save it. Or, more specifically, the moment Inco realized that the dust wasn’t just unpleasant, but was damaging mining equipment.

In nature, earth and soil are kept from blowing around by vegetation, which helps bind the soil with a tangle of roots. So the mining companies, in an effort to appease angry locals but also to save their equipment, thought of a not-so-novel solution: they tried to grow grasses on top of the tailings, hoping this would get a handle on the dust.

It was no easy task. Since the tailings were highly acidic and virtually lifeless, nothing would grow. But in a series of experiments in the mid-1950s, Inco and its local rival, Falconbridge Ltd., found some success. Inco’s method, adding a combination of limestone and fertilizers while planting crops like rye, allowed the grasses to take root.

The companies weren’t thinking of any bigger implications—they just held onto that recipe for restarting nature, almost hotwiring plants, focused all the while on their narrow profit goal: containing the dust.

Sudbury in the sixties was, in a few senses, a black mark on Canada. It was one of the largest sources of sulphur dioxide in the world. At scientific conferences, the word “Sudbury” was used as a unit of pollution, says Laurentian University environmental science professor John Gunn. “My first conferences I went to, in Ithaca, New York, when the European countries were being confronted with their own pollution statistics, they would graph it relative to a Sudbury unit,” he says. Most would be less than a quarter of “a Sudbury.”

It put Canada in an awkward spot, diplomatically speaking. If Canadians could have one city polluting more than entire countries, who were they to lecture others on cleaning up their act? And we were beginning to try to lecture others; the scattered environmental movement was coalescing, with Greenpeace founded in 1971 in Vancouver.

Until the late sixties, government hadn’t done much to force polluters to improve. But now it began paying attention. A watershed came in 1967, when Ontario passed a law limiting emissions, with the focus on ground-level pollution and air quality.

But at the time, technology available for improving the smelter was limited. So Inco went with the least-bad option: a bigger smokestack. Called the superstack, it’s the second-largest chimney in the world, 381 metres high. When it was completed in 1972, it was the tallest building in Canada until the CN Tower was completed four years later. The superstack wouldn’t limit overall emissions, but it would lessen damage to Sudbury by making sure the pollution was released so high it would be scattered further afield.

This, of course, created new problems; a 1982 study using computer modelling estimated about 5.5 percent of the sulphur deposited on the soils of Nova Scotia could be attributed to Sudbury smelting. Still, sulphur dioxide emissions had dropped by about half around Sudbury in the early seventies. It wasn’t just the superstack; Inco had also closed an obsolete smelter, and Falconbridge had closed a money-losing iron processing plant, which on its own accounted for half that company’s SO2 emissions drop.

Apathy gone, the Ontario government created further restrictions in 1978. Then, in the mid-1980s, newly minted premier David Peterson picked his cabinet, including one man who had grown up living in the shadow of the Inco smelter: Jim Bradley, who was named environment minister. Bradley, now seventy-four, says his early childhood in Sudbury wasn’t all great: where most kids might have a park near their house or maybe an alley to play in, he grew up next to a hill of blackened granite.

The mining giant didn’t take to Bradley’s regulations lightly. “Countdown Acid Rain,” as the program was called, asked Inco to cut emissions by 60 percent in under a decade.

Inco, foreseeing that a hammer would be brought down, had slowly started proposing its own changes. Now it balked, saying the price tag was too high and the technology didn’t exist to do the upgrade—it might even put the company out of business. Inco’s then-CEO Charles Baird told reporters that getting it done would require building a completely new smelter, saying he was “disappointed” in the government’s lack of understanding. But in the end, he said the company would study the matter in the three years they’d been given to write a plan.

Then a funny thing happened, Bradley recalls. At the end of those three years, Inco executives arrived in Toronto for a press conference about their progress. As they unveiled their materials, Bradley saw they had redesigned their logo—with a green outline. “I was amused, but delighted,” he recalls.

But there were more surprises. The Inco representative there that day, Roy Aitken, announced that the company would be able to meet the regulations, entirely with its own cash, at a cost it estimated at half a billion dollars. More than that, it would exceed the law’s provisions. And, Aitken said, one part of the operation would make a profit of about 18 percent, and another part of it, 6 percent. More than three decades later, Bradley still remembers the numbers.

Gunn knew Aitken, and once he asked him what happened. “He had three answers, which I believe were all true,” Gunn says. “One was that his kids were cross at him for running a dirty company.” Another, which he was more private about, was workers’ health; Aitken himself was suffering from lung cancer at the time. He had once worked as a student miner.

“The other one that he spoke more loudly about was that in a major corporation, to headhunt, you’re competing against Silicon Valley and Toyota and others,” says Gunn. Image was everything. To Aitken, those factors—the company’s image, its effect on workers’ health and its recruiting ability—were all essential for Inco’s long-term viability. “He thought there was enormous financial value to all three of those things that are beyond the moral requirements.”

The new appeal of a clean, green image, of course, was outside Inco’s control. Starting in the sixties, a whole generation had been galvanized for protest. “Smog episodes” in London, Tokyo and New York shocked people around the world. One citizens’ group, the Canadian Coalition on Acid Rain, was lobbying on both sides of the border and boasted some two million members. “They knew, politically, how to change people’s minds,” says Bradley.

And government still had its own strong motives for applying pressure. Sudbury’s bad reputation had continued to dog Canada abroad. During acid rain treaty negotiations with the United States, which began in 1984, the Canadian government contended that about half of the acid-rain damage to lakes and forests came from polluters south of the border. But American negotiators would use Inco as a cudgel “within five minutes,” Bradley says. Once Inco’s improvements became clear, the tables turned and Bradley began bringing up Sudbury.

In 1995, an Inco analyst named Dan F. Bouillon wrote about the struggles within the company to meet Bradley’s emissions targets over the previous decade. Or maybe “struggles” isn’t quite the right word. “In addition to the environmental benefits of the new smelter, there are considerable economic benefits from the new facility,” Bouillon wrote. He estimated it would take the company about ten years for the project to pay for itself, to the tune of $600 million.

It turned out that even the smelter’s waste could be turned into profit. When it’s not released as smoke, sulphur dioxide can be converted into sulphuric acid, which has a variety of industrial uses, from fertilizer to car-battery acid. Capturing it requires building something called an acid plant, and then the acid can be produced and sold with a net gain. This process was already well known; Inco’s first acid plant was built in the early 1930s. But the idea of catching all the SO2 methodically—increasing capacity to make sure they got it all—only took hold when Inco opened its new acid plant in 1991.

Inco kept making changes. A new milling process reduced sulphur in ore sent to the smelter. A new smelting furnace gave off more concentrated SO2, an output better suited to the new acid plant. And, Bouillon wrote, the company found it could turn around and market the technologies to other mining firms that wanted similar upgrades.

Sudbury’s cycle of improvements has kept up ever since; the latest step is a $1 billion investment at the Copper Cliff smelter in the city’s west end, called the Clean Atmospheric Emissions Reduction (Clean AER, pronounced “air”) project. It’s a response to 2005 regulations put in place by yet another Ontario government.

As emissions have steadily lowered, improvements have become harder. Gunn calls the earlier smelter upgrades the “low-hanging fruit period.”But overall, it’s hard to overstate how quickly, and how dramatically, SO2 emissions have dropped. The Copper Cliff project, completed last year, decreased emissions by 85 percent compared to a decade ago, according to the company. The company’s total sulphur dioxide emissions are already just 1 percent of what they were in the early seventies.

None of this has necessarily been great news for the planet’s overall climate—that is, for Sudbury’s carbon output. In fact, it’s been the opposite. The smelters have needed to use more heat for the tall smokestack. Since it’s so tall, extra heat is required to keep the SO2 hotter than the condensation point and therefore stop it from forming sulphuric acid, which corrodes the smokestack’s steel liner. It’s one of the ironies of the smelter: it’s had to increase carbon emissions to decrease sulphur ones, at least until it could figure out a technological solution to avoid that trade-off. When the superstack shuts down in 2020, not only will Sudbury lose the iconic chimney that defines its skyline, it will see a 40 percent drop in the operation’s greenhouse gas emissions.

The Clean AER project didn’t recoup its costs as much as the earlier cleanup. But Vale—as Inco is now known, after a sale in 2006—found ways to squeeze revenue out of it. Updated devices, somewhat like enormous kitchen fans crossed with aircraft hangars, diverted an even greater percentage of sulphur gas to the acid plant. It added an extra “secondary baghouse,” where specialized vacuums trap metal particulates like nickel. That captured metal dust can be fed back into the system and sold rather than escaping into the atmosphere.

“They were losing ten thousand tons of nickel and copper particulates in the dust fall,” says Gunn. “A lot of the answers were selfish economics: ‘How can we convert waste into product to offset the renovation [and] modernization costs?’”

In 1990, around the time Roy Aitken was astonishing government types in Toronto with his boundless cooperation, he gave another speech, this time in Sudbury. Here he seemed to say what he really felt.

“There are certainly lots of politicians who have suddenly developed green tendencies. The road to Damascus is a continuous traffic jam populated by limousine-driven politicians who are scrambling to get on the bandwagon of the one issue where they can do no wrong,” Aitken said.

But it’s easy to make rules, he said, if it’s other people following them. More than that, the green movement revealed just how little politicians understood the industries they claimed to direct. “How can business people cope with this rate of change?” he asked wryly. “Because, after all, we are routinely categorized and castigated as short-term thinkers who can’t see beyond the next quarter’s results.”

In fact, in his world, he reminded the audience, recovering investment in a new mine could take up to twenty years. “Compare that for a moment to the attention span of the typical government elected official in power for a four-year term, the last two of which are normally focused on re-election,” he said. “The pressures to think long-term for the businessman are enormous. They don’t compare with the politician’s time span.”

As for the average voter, he said, that was the worst-case scenario: “The really short-term thinker, the private citizen, the ultimate polluter, who enjoys his coffee out of a polystyrene coffee cup, good for ten minutes and garbage for a hundred years. What about his long-term thinking?”

Aitken never got to see the full fruits of his contribution. He died in November 1992, at the age of sixty, before Inco actually met Ontario’s emissions target. But in the end his vision, and the logic behind it, held true; his company saw massive, long-term savings through the cleanup in the form of lower energy use, higher productivity and reduced maintenance. That Inco, and later Vale, were able to remove the stain from their names was just a perk.

For a time, Gunn served as an unpaid, arms-length critic on Inco’s environmental advisory board. He grew to believe that one of industry’s biggest hurdles is simple inertia, rather than real financial risk. Inco’s changes benefited it in countless ways, but that “wouldn’t have happened without strong government regulations,” he insists.

But another lesson Gunn took was how long it could take science and technology to enter into practical use—including the company’s own science. Observing the board, he was surprised to realize that much of the technology to do things like capture sulphur dioxide emissions was already available in-house. Sometimes it was designed long, long before it was used.

“I realized at the time that the engineering groups, the people with solutions, were not able to get to the boardroom table until it was an emergency—that they had to meet deadlines and meet regulatory requirements. And then all of a sudden, a lot of really smart solutions were already on the shelf,” he says. One example was the pre-existing acid plant design. Another was the eighties’ upgrades to the smelter’s copper-nickel flash furnace, which weren’t designed from scratch but adapted from an older design.

To talk to people at Vale now, you’d barely realize the company ever harboured doubts about reducing emissions. Cory McPhee has spent thirty years first at Inco, then Vale, where he is now Vale Canada’s vice-president of corporate affairs. “Don’t underestimate what’s possible,” he says. “I can tell you that the people who were involved in…the SO2 abatement project probably never envisioned us getting to where we are today. But the world changes, technology changes, new bright ideas are brought to the conversation.” More than that, it’s not hard to stay “collaborative,” he says. “I don’t think government goes into these conversations with the intention of driving business into the ground.”

What matters now is whether Vale, and companies like it around the world, have learned these lessons in a more permanent way—whether they tend to see reducing emissions as a boon, even when not compelled by law. Is it possible that they’re working towards ambitious carbon targets, even while pessimism rules?

In Vale’s case, the answer looks disappointing, at first glance. In 2012, the company pledged to reduce carbon emissions for its global operations by just 5 percent by 2020.

But things may be better than they appear. According to the company’s most recent sustainability report, emissions had already dropped, by 2017, about 8 percent from the baseline emissions of 2012. In other words, three years before the end date, the company was already well ahead of its goal.

It makes some sense for companies like Vale to set low expectations on paper, says Nadine Ibrahim, a civil engineering professor at the University of Waterloo. They face technological uncertainty: they know how, and exactly how much, they can reduce emissions with existing tech. But many of the world’s targets for 2050 build on the assumption that new technologies will be invented, making it easier to aim low and then overachieve. (McPhee, speaking for Vale, says the 5 percent reduction goal isn’t necessarily underwhelming. Reducing emissions “is kind of a never-ending journey,” he says.)

And just as with its sulphur emissions, Vale isn’t cutting back on carbon out of altruism, and that means it may well keep exceeding expectations. Its executives have recognized that climate change “will hurt their bottom line,” Ibrahim says. “Which is not to say that that’s a bad way to approach it; it’s actually the incentive.”

In its sustainability reports, aimed at investors, Vale lists a series of risks from potential climate catastrophe, but also from a world that accounts for carbon. It has been preparing to satisfy, for example, consumers seeking out less carbon-intensive products—or a tax likely on the horizon. “Vale has...developed an internal tool to quantify the potential risk of carbon pricing in its business,” it reported to investors in 2017.

It’s enough to make one optimistic. If politicians keep at least talking about carbon crackdowns, maybe the threat alone makes it financially prudent to factor that in.

In fact, it does; that’s already becoming clear for those who study the world’s biggest resource companies, including the handful of oil and gas giants known as the “majors.” “Shell, for example, has been a front-runner in recognizing climate change and seeing the writing on the wall,” says Miriam Diamond, an environmental science professor at the University of Toronto. “They’re trying to get ahead of the curve.” Shell has committed to investing $1 billion to $2 billion per year in alternative energy; if it keeps to that plan, it could halve its net carbon footprint in the next three decades.

Not all oil giants are the same; the US-based ones lag behind, especially ExxonMobil, which for years spread climate-change denialism. It has no emissions target at all.

But among those tackling carbon, again, it’s for pragmatic reasons, and they are likely working far ahead of the schedule the public sees, says Valentina Kretzschmar, a research director for energy consulting firm Wood Mackenzie.

For one thing, going greener helps with “attracting talent,” Kretzschmar says—logic that echoes Inco’s in the 1980s. “Oil and gas companies are becoming less and less popular, less attractive to young people,” she says. “They want to work for clean companies.”

Investors are a big source of pressure, Kretzschmar says, especially in Europe, where long-term investors want companies like Shell to “future-proof” themselves, and activist investors specifically want to force change. But, like Vale, most oil companies don’t need much coaxing to openly acknowledge the looming risks to the worldwide economy. They see “a very big picture,” says Kretzschmar, and downplaying the problem doesn’t tend to be part of their strategy.

In fact, government is holding them back. To really shift operations, the majors need a heavy influx of capital that will only come when politicians signal that new taxes are on the way. “They are investing in some technologies like carbon capture and storage, but these technologies are still very expensive, and they’re not profitable,” Kretzschmar says. Carbon taxes would spur investment in those methods, she says. “They’re waiting for a push by the government.”

Nearly identical patterns hold true in mining. And it’s just as pressing; many of the materials that will emancipate us from fossil fuels will need to be mined, whether copper for lines to transmit electricity, alloys to build wind turbines or the metals that go into batteries. “Mining has a really important role to play in helping us transition from carbon fuels,” says Anne Johnson, a sustainability and mining expert at Queen’s University.

With policy-makers waffling, much of the push for lower-carbon mining also comes from investors, Johnson says. They can’t compensate for the action government can compel—crackdowns like Sudbury’s—but they make a difference. And some of investors’ thinking comes, in turn, from consumers. Buying products labelled “sustainable” might seem pointless, but those preferences do trickle, however minutely, from manufacturers to raw-material suppliers. As with the oil majors, “it’s ultimately the market that allows you to do the progressive, responsible things you might want to do,” Johnson says.

Right now one industry goal is to reduce the energy needed to crush and grind ore. New methods can halve energy consumption, and the federal government is boosting further experimentation with a multimillion-dollar contest. But even without public money, current investments like that will unquestionably pay off down the road, Johnson says. She predicts “that same pattern [as] Sudbury, where it seems like so much money up front, and yet ten years on you think, ‘Wow, we actually saved money.’”

McPhee says Vale is experimenting with electric vehicles in some underground mines, replacing the diesel fleet, and with tunnel-boring technologies used in urban subways that would allow them to reduce the use of explosives. But perhaps the biggest focus is reducing energy, which McPhee says is the company’s biggest expense after labour. “Good energy management is actually good business sense as well,” McPhee says.

Vale won’t be backing off such experiments, regardless of government’s changing winds, he says. They “contribute environmentally, they contribute to [the] workplace environment, they contribute to safety.”

None of this is to say that the problem will be fixed as quickly as it would with active governments. Bradley said one key to cleaning up Sudbury was not just giving deadlines, but strict ones—he knew this because Inco executives later told him.

“What business and industry wants to know, they want to know ahead of time,” Bradley says. “They may fight you on it...but they want to know ahead of time what you’re going to do. And then you have to stick to it.” Short, successive deadlines were also crucial; the company was asked to report its progress every six months. That way, Bradley says, “they couldn’t come back at the end of three years and say, ‘Guess what? We can’t afford it and we can’t do it.’”

As for the local landscape? Sudbury would be unrecognizable to a miner of 1970, and that story is also, perhaps, a blueprint for the future. Sudbury didn’t regrow naturally.

Instead, it all started when massive layoffs swept through Inco in 1977, as nickel prices plunged. More than 3,500 workers lost their jobs. Suddenly, there was a large labour pool. The government, worried about skyrocketing unemployment levels, including among the young, created something like the American New Deal of the 1930s, but on a local scale—and for plants.

As emissions had gradually abated since the sixties, provincial and municipal governments had been talking about a massive regreening effort, but it hadn’t gone anywhere. Now the government put laid-off miners to work, but in this case rebuilding natural infrastructure: something that would allow nature to take its own hold on a wasteland.

In 1978, the regreening began in earnest. Students, no longer offered summer internships, were let loose throughout the area, spreading lime and planting grasses and other plants. They started with the most damaged corridors, particularly a stretch of highway going north of town. A few years later, tree-planting started.

The results were just as dramatic as the emissions decrease and even more visible. By 1984, after just one year of tree-planting, 388,000 trees were growing on 2,500 hectares, with the regreening employing more than 2,800 people. By 2010, 9.2 million trees and more than fifty thousand shrubs had been planted by 4,536 workers and 9,981 volunteers. More than three thousand hectares of land were limed, fertilized and seeded. And in recent years, strips of forest floor taken from a nearby highway expansion have been spread through some of the more damaged areas to bring back much-needed nutrients and undergrowth to the landscape.

The changes can be not just seen but also tasted. Marc Gascon is the co-chair of Clean Air Sudbury, a community group formed in the late 1990s to track local air quality. Growing up, Gascon says, he heard stories of the choking sulphur, and of “the ladies yelling at their husbands from their houses” because the smoke was so thick. He remembers the sulphur taste in his mouth. “I haven’t had that taste in the summer months in probably at least fifteen years,” he says. Bradley says the hill at the end of his childhood street is no longer barren.

And yet the ore still comes out of the ground, goes into the furnace and comes out the other side as nickel. No matter how lost the causes seemed—even something as simple as getting grass to grow—they ended up being, business-wise, the most natural thing in the world.