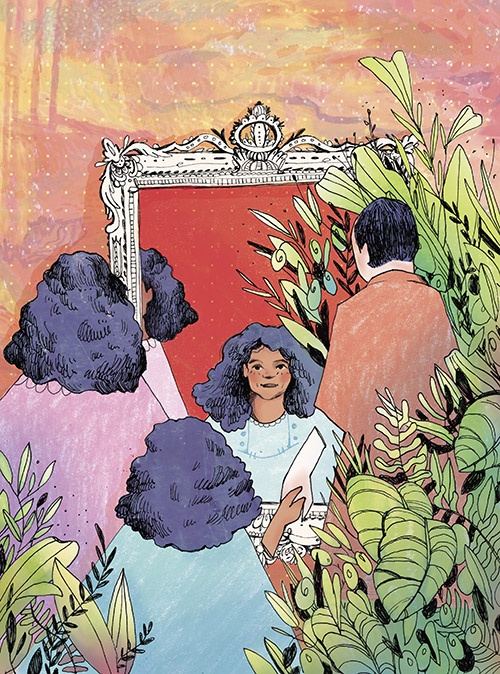

Illustration by Isabella Fassler.

Illustration by Isabella Fassler.

Broken Up

These days people love the idea of interracial marriages, Natalie Harmsen writes, but that’s different from trying to make one work.

It was the second week of university. The second week since I’d packed up all my faded jeans and beat-up sneakers, since I’d moved into a shoebox of a dorm room with a complete stranger. Despite the close quarters, I was ecstatic to be in residence. I cheerfully ignored the dingy peeling walls in burnt orange and navy blue, and disregarded the grungy carpet.

The day I had moved in, I was so eager to be on the cusp of freedom that I forgot to hug my parents goodbye. So when my dad came for a visit fourteen days later, to fix my printer and check up on me, I didn’t think anything of it.

But he’d been acting strangely the minute he arrived, armed with a new ink cartridge. The air was sticky because the windows in the building didn’t open. The sizzling glass amplified the sunbeams around the room. I figured his awkwardness was his way of coping with missing me. How bad could it be? I thought. He had my mom and my sister, so it’s not like he was stuck alone in an empty house.

It came time for him to leave for the two-hour drive back home. “Can we say goodbye in the car? Without your roommate,” he said.

I sat in the passenger seat, frozen. His words tumbled out, faster and faster, uncalculated and uncontrolled. I tried to process calmly. My parents, married for twenty-three years, were splitting up. I knew they fought a lot, but didn’t everyone? I felt duped.

The car pulled away and I waved, pretending to smile as the sun felt increasingly hot. I stumbled up the concrete stairs to my room, my face, like my world, on fire. I began bawling.

The news overwhelmed me, but I also had a funny feeling creeping into the back of my head. Even though I hadn’t seen the split coming, I should have.

Divorce was a regular part of my childhood, as common as Tamagotchis and fruit rollups. I grew up with countless friends who lived with only one parent. After all, Statistics Canada found in 2011, the last year they surveyed the issue, that approximately five million Canadians had separated or divorced within the previous twenty years. And marital dissolution is on the rise, according to the Vanier Institute of the Family; in 2017, an estimated 9 percent of adult Canadians were divorced or separated. Every split is unique of course, but the main factors in Canada include the pressures of living together, the challenges of committing at a young age, having differing education levels or raising stepkids.

I can think of over fifty reasons why my parents split up. My dad loves fishing, boating and hunting; he is one with the outdoors. My mom can’t swim. My dad is a slob; my mom washes our kitchen floor until her hands become ashy. The list goes on.

Still, one difference set my parents’ relationship apart from other couples I knew. My mom is black, from Guyana, a country almost none of my white friends can find on a map, while my dad is white, with Dutch immigrant parents.

Movies like Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, Something New and Loving teach us that love always triumphs in the face of bigotry. As long as I can remember, pop culture has treated all these films the same way. The narrative arc goes like this: an interracial couple gets together, they face backlash—either from their families or the law—they split up or nearly split, but they always end up together. At the end, racism is magically solved and everyone lives happily ever after. No matter how high the deck is stacked against you, there is always a way through.

Mixed partnerships are on the rise in Canada, seemingly good news. Of all married and common-law couples in Canada, 360,045 were in mixed unions in 2011, almost twice the number of two decades earlier, according to Statistics Canada.

But just because this number is growing, that doesn’t mean these couples are staying together. Things are very different off-screen; interracial couples face many challenges that same-race couples do not. Research backs this up: “On the whole, interracial marriages are less stable” and have a higher risk of separation or divorce, researchers Yuanting Zhang and Jennifer Van Hook found while studying marital dissolution among American couples. What’s more, they found that the risk of splitting was highest among black and white couples, like my parents.

Here in Canada, where multiculturalism is worn as a shiny badge of honour, we tend to shy away from discussing this reality—we are, I think, generally unwilling to address racial tensions for fear of tainting the idea of Canada as a perfect mosaic. There is very little data and research on the success rates of interracial marriage in Canada. Statistics Canada hasn’t even tracked mixed unions since 2011.

It reminds me of how my own family has struggled to talk to each other about what we’ve experienced.

My parents’ story started out as a simple one. They met at a party in Kingston, Ontario in 1984. He asked her out. They went for many dinners together, often stealing the bread to take home and eat later. They bought a bungalow that my dad fixed up over several years, putting in hardwood floors, rebuilding and remodelling. When my sister was born, they built an upper level on the house that became their bedroom. They painted it sunshiney yellow and he built my mom a walk-in closet for her many pairs of statement heels.

When they got together, they didn’t realize there would be so many struggles. I don’t think they ever talked about race.

Then my sister and I were born. When I was little, my mom gave me a doll named Alison. She was beautiful and black, with twists in her midnight hair and a fuchsia velvet dress with matching shoes. She was darker than me, but looked more like me than any blonde Barbie. My mom knew it was important for me to have a doll like that. My dad never bothered to look for such a toy; when your skin colour is represented everywhere, you don’t really think about what it must be like when it isn’t. This was just how life was: one parent was conscious of what it meant to be racialized, while the other lived blissfully unaware.

When Zhang and Van Hook studied marital dissolution in 2009, the idea of “homogamy”—marriage between people from similar cultural backgrounds—turned out to be key. Profiling more than 23,000 married couples, they discovered that most couples with similar characteristics have “fewer misunderstandings, less conflict, and enjoy greater support from extended family and friends.” And mixed unions involving black people were the least steady. The social discrimination against such couples could be especially harsh, likely reflecting society’s persistent racism and distrust directed toward black people.

Maybe my parents felt lucky; at least they were allowed to get married in the first place. Interracial marriage was never officially banned in Canada, unlike the United States where the first anti-miscegenation statute was passed, in Maryland, in 1661. Harvard economics professor Roland G. Fryer Jr. has written that anti-miscegenation laws went hand in hand with slavery, working to “draw a distinction between black and white, slave and free.”

In fact, these laws were more extensive than segregation or slavery, existing in forty-one of the fifty states at various times, and only finally overturned for good in 1967—only fifty-two years ago—by the US Supreme Court in the civil rights case Loving v. Virginia.

Though Canadian laws didn’t explicitly prohibit interracial marriage, the government did help prevent it. Canada’s Indian Act was one example, argues University of Oregon political scientist Debra Thompson. Not only was it a tool of assimilation, but it deterred interracial marriage by decreeing that if an Indigenous woman married a non-Indigenous man (or non-status Indigenous man) she would be “expelled from reserve lands, expunged from band membership lists and denied access to federal services designed for status Indians only,” in addition to losing her connection to her culture. That stipulation was introduced in 1876, and it wasn’t amended until 1985.

Black and white couples in Canada may not have faced legal restrictions, but they did face intense discrimination. In 1924, for example, members of the Ku Klux Klan surrounded the home of a white man in Dorchester—near London—who was believed to be married to a black woman. And on the night of February 28, 1930, seventy-five Klansmen marched through Oakville, Ontario to punish Ira Johnson, a black man, who was living with Isabel Jones, a white woman. They forcibly removed Johnson from the home where the couple was staying and nailed a cross to his door, set it ablaze and threatened to “attend to him” if he was seen with Jones again. Oakville’s mayor, A.B. Moat, said at the time he thought the Klan acted “quite properly in the matter.”

This hatred is still very much alive today. In 2010, a heartbreakingly similar attack was made on an interracial couple living near Windsor, Nova Scotia. Shayne Howe, who is black, and Michelle Lyon, who is white, woke up to find a flaming cross and a noose outside their home. Twenty-year-old Justin Chad Rehberg was found guilty of inciting hatred; the case marked the first time a cross-burning was recognized as a hate crime in Canada.

And, of course, the discrimination isn’t all criminal. A good chunk of the population still has apprehension about getting into mixed relationships—15 percent of Canadians say they would never be with someone outside their race, according to a 2019 Ipsos poll. Some reported it was because of pushback from family, while others said it has to do with what society tells them is attractive. This societal instruction is often steeped in anti-blackness.

Regardless, I can still feel this attitude sometimes, from some people; it radiates off them like a cloying perfume. When I walk down the street and see mixed couples hand in hand, I also see the stares they get. I’ve felt the electric shock of the same kind of glances.

When I was growing up in Kingston, it was always my dad who did the grocery shopping. He’d take my sister, my Oma and me to the No Frills near our house.

My dad is the kind of person who commands attention wherever he goes. Not only is he six-foot-four with a large mustache, but he’s also very loud, unabashedly outgoing. On these excursions, he always ran into someone he knew. While they were chatting, I could feel the stranger’s eyes flitting down to survey my sister and me, taking in our brown skin and flyaway curls. Eventually, they would ask, “So, are these your daughters?”

We would stare back and say nothing. It never quite made sense. On one hand, we look nothing alike. My dad has eyes such a bright sea-blue I could always see my dark brown ones reflected in them. On the other, I was almost certain that when my friends went out with their parents, people never questioned if they were family. I began to wonder if other people assumed I was adopted.

My dad never really noticed—or if he did, he never said anything. It was always uncomfortable, but I couldn’t fully unravel my emotions; my thoughts became heavy with confusion. If we were out with my mom, I was a bit more at ease because I knew people were looking at all of us; we were in it together.

I’m sure the ogling and the questions are a regular part of life for most mixed kids, and there are a lot of us. According to Statistics Canada, 340,000 children in the country are part of mixed-race families.

But the growing population of mixed children doesn’t necessarily change anything about the society they live in. In fact, in many ways kids like me and my sister bear the brunt of society’s self-delusions. Sure, multiculturalism became Canada’s official policy in 1971. It’s woven into the fabric of my mother’s silk headscarves and melded into my Oma’s wooden shoes. But it’s easy to equate multiculturalism with open-armed acceptance, instead of—more often the reality—a lukewarm tolerance of people darker than the rest.

“Mixed-race folks may be seen as those perfect examples or embodiment of multiculturalism because they’re seen as this perfect product of inter-unions,” says Leanne Taylor, an associate professor in education at Brock University who teaches issues of race and racism. “This is the image of Canada that we’re wanting to sell,” she says. “What better way to sell this image than by showing the products of interracial love, so to speak?”

Mixed families can also contribute to this myth-building in another way. UBC professor Minelle Mahtani, who wrote the book Mixed Race Amnesia: Resisting the Romanticization of Multiraciality, has used the term “cocooning” to describe a dynamic that plays out in some mixed-race homes. Some parents of mixed-race kids wouldn’t tell their children about the racism they experienced, she found, in order to make their home life happy and safe. In turn, when these kids faced racism, they didn’t discuss it with their parents for fear of tainting the parents’ supposed view of the world. This silence further fortifies the impenetrable bubble of multicultural sunshine.

In the fourth grade, I was one of the only people of colour in my class. I had long curly hair that was twisted into braids, while the other girls sported pin-straight ponytails. We all sat in clusters, our grubby crayon-filled desks pushed together in groups of six. After lunch one day I found Aaron, the sandy-haired neighbour who sat across from me, wasn’t there, and another classmate, Brandy, was sitting in his seat, talking loudly. Aaron came back and asked if he could sit in his chair.

“No, go find another one,” Brandy smirked.

“Can I please just have my chair back?” Aaron asked again.

“Just let him sit in his chair,” I piped up. Her hazel eyes bore into my dark ones threateningly.

“Did you know that John has tools that he uses to kill black people?” she said, smiling. John was another white classmate. He had never been mean to me. I stared at her silently. “He has all these tools that he could use to hurt you.”

Nine-year-old me didn’t give her the satisfaction of reacting then and there. But when I got home, I sat on the stairs leading down to my basement and sobbed until I was hollow. My dad brushed the entire incident off, laughing as he told me not to cry.

When my mother got home from the office, she was furious, transforming from her weary post-work self into a supernova of rage. I remember that she called the school to tell them exactly what had transpired, while my dad did nothing. I didn’t understand why he thought it was so funny. He and I never talked about it again.

My parents constantly clashed when communicating about race. My mother would bring up incidents that made her uncomfortable, things that today we call “microaggressions,” like someone at work acting as though she wasn’t qualified to do her job, even though she has a master’s degree. There wasn’t a word for this kind of behaviour back then, but microaggressions, of course, have been happening since forever. They are common, everyday, sometimes (but not always) subtle, racist remarks or behaviours directed at people of colour.

And my dad just didn’t seem to understand what that meant for my mom. He always got angry, denying that anything had happened. My mom would snap that she was used to these occurrences and he’d never understand. It was a cycle that repeated over and over again.

My sister and I usually sat in the living room, listening as their voices grew louder by the second. The room felt like glass. She would eventually retreat to her bedroom, while my dad would slip outside to the garage. Afterwards there would be an ocean of tension between them. It was frustrating, but it became my normal.

Interracial couples face a different—or extra—kind of trust issue than other couples, says Taylor. “If one partner is experiencing racism and the other isn’t, or doesn’t see it, or refuses to see it, or is unable to see it, then that’s going to create some tensions,” says Taylor, who is a mixed-race woman herself. The racialized partner will often think, “‘Well, don’t you trust that I’m experiencing these things? Don’t you believe that this is my life?’” she says. “It kind of wears on [their] connection if there isn’t a willingness to see or understand how your partner lives and experiences the world.”

Harvard psychologist Holly Parker has written that in the face of this kind of dismissal, the racialized partner faces “a painful decision. They may either decide not to continue opening up to their white partner, or find themselves in the difficult position of always needing to defend their impressions of what’s happening (which sounds exhausting).”

Michelle Richards, a clinical social worker and therapist in Mississauga whose work is grounded in principles of anti-racism and anti-oppression, says “there are a lot of people that say ‘I don’t see colour.’” But “that’s crap, because if you don’t see colour then you don’t see me, you don’t see racism,” she says. If counselling a person of colour in a mixed relationship, she’d have questions for them, too: “What were your expectations when you got with somebody who is not of colour, and what conversations did you have?”

There are ways to work through these problems; Richards says the white partner needs to develop an understanding of racism and discrimination that would allow them to be comfortable talking about the turmoil of it—and not only that, but they need to get used to standing up publicly for their partner. She also suggests the racialized partner seek friends who are people of colour who can understand their experience in a way their partner cannot. “When racism or discrimination is a part of your lived experience, you can go crazy sometimes wondering if this is really happening, so it’s important you find people you can talk to.”

I think about this issue of trust, now, every time I see a mixed couple walking down the street; I hold my breath and hope they don’t have similar culture clashes to my parents’.

I look back at family photos, trying to find evidence of some sort of turning point. There’s one from about eight years ago—I was fourteen—when we were on vacation in Paris, looking happy and relaxed. In these slices of frozen time, the clouds drift away and everything seems so simple. It’s easy to remember the good parts.

But maybe the change happened eventually, as the years went by. My mom stopped trying to talk to my dad about any microaggressions in her life. I think she lost the will to fight him. Or maybe she was just so tired from living through racism outside the house that she didn’t need it at home, too. Neither of my parents were willing to talk to me about their relationship when I told them I wanted to write about it.

I do know that when I left home for university, my old normal became exactly the opposite. I was suddenly surrounded by a sea of people from all over the world. On one hand, I was hyper-aware of race, as my journalism program was mostly white, but I soon realized that other classes, and campus as a whole, were extremely diverse; there, I didn’t stick out, and I wasn’t afraid to immerse myself.

My understanding of everything became enriched. I took classes that went miles deeper on race and human rights than anything I’d learned before. I read Jesmyn Ward and bell hooks; I watched documentaries on the Sir George Williams riot and I learned about the history of racism in marketing campaigns.

With that knowledge, new reflections on my parents’ marriage came in waves, crashing into reality. In September 2014, during that first month of university, a man named Jermaine Carby was shot in Brampton during a routine traffic stop. When I went home for fall reading week the following month, the group Black Lives Matter Toronto had formed.

As the nation watched Carby’s family grieve, I was in mourning for my own. My dad had moved out. I unpacked my suitcase, looking out at the trees from my bedroom window. The leaves had extinguished themselves in fiery oranges and yellows, laying crumpled all over the ground, and I felt a profound, aching sense of loss. But over the course of that week, I realized that I’d also gained something: my mom and I now talked about race more openly than before, and we could do so without my dad downplaying anything.

The walls between my parents grew brick by brick. But in the end, they didn’t just separate the two of them; they also separated my dad and me. His inability to understand my mom’s experiences was the same inability to understand mine.

The bricks stand unwavering, and it’s frustrating—yet as much as I want resent him for that, I don’t. He’s lived a privileged life at the top of the racial food chain. I don’t think he can ever fully comprehend what it’s like for those in the dogfight at the bottom, competing for a seat at the table.

I like to think that seeing my parents’ relationship crumble makes me more than equipped to avoid the same situation. I know that I won’t tolerate someone who ignores the injustices people of colour face. If, when I bring up my heart breaking over another black man getting shot, or discuss the impact of affirmative action, I receive pushback instead of listening, I know it’s not going to work. I think I understand what my mom went through, being surrounded by a family of white relatives who couldn’t relate to her.

But my parents’ marriage also showed me not to shy away from people who are different than myself, because real love should be kaleidoscopic: all skin colours are beautiful.

As I’ve gotten older, I’ve followed über-famous mixed couples, like Prince Harry and Meghan Markle’s historic union or Nick Jonas and Priyanka Chopra’s whirlwind romance. These stories fascinate me—it’s like watching my own life, magnified, but also at a safe distance. The public’s bigotry becomes clear, though always in different ways. Sometimes the public response is negative—simply racist. Sometimes it’s positive, but then it exoticizes or fetishizes them. “What beautiful mixed babies they’ll have!” people gush.

When Harry and Meghan got together, it made my heart soar. A biracial black woman like me was going to be a royal. She was going to be in one of the most well-known, whitest families on earth. I worried for her, but I also knew how important she would be as a role model for other mixed girls, and how black people would feel seeing themselves represented.

Then, the comments rolled in like a storm. From every outfit she wore to every wave or handshake, the public had something nasty to say. The media coverage went beyond scrutiny—it was vicious, even scathing. Many of the internet trolls hid behind other ostensible reasons for their dislike: that she’s American, or that she’s been divorced before. But I don’t think so; I think the heart of it is hatred for the part of her they wish didn’t exist—her blackness.

Still, she seems to be holding steady, being unapologetically black and herself. At the wedding, the musical choices were steeped in black history, most memorably the use of “Stand By Me.” The song became popular during the civil rights movement and was performed at the wedding by an all-black choir, making the significance of the tune clear. Her most recent stint as a guest editor of British Vogue confirms Meghan is calculated in her efforts to empower black women, through her selection of several black artists and activists for coverage. For that I’m thankful.

At the same time, seeing her and Harry together, looking happy, makes me wonder if all the animosity she endures is worth it. Does she love him enough? Does he love her enough? And I’m nervous for baby Archie: he’ll grow up in the thick of it all, having to navigate his mixed-ness while the world watches his every move.

I know I have vast privilege as a lighter-skinned woman, compared to other black women. But to be mixed is to always be walking a tightrope: black people don’t see you as being truly black, and the rest of the world doesn’t consider you to be white. Meanwhile, strangers freely police your identity. “Where are you from? No, where are you really from?”—I’ve heard this more times than I can count. There’s also my personal favourite, “What are you?” Classmates, new co-workers, Uber drivers—the world feels free to pummel me with these questions. “You must be Hispanic,” they say. “I never would have guessed you’re black! You’re so light-skinned!” Everyone wants to play a guessing game of how my parents got together. I used to think it was kind of funny. Or rather, like the way I understand my father, I couldn’t blame them for their ignorance because all the couples they knew were white.

I was once on a date with a guy in Ottawa, just as winter announced itself with a sea of white. The streets were newly slick with ice and we shuffled along, holding on to each other like cling-wrap, desperately trying not to fall. We went for pizza to seek refuge from the sharp wind, and eventually brought it back to his house. I was curled up on his living room couch. He turned to me and, out of nowhere, asked the eternal question—“So what are you?” I took a bite and almost forgot to chew it.

“If you can guess, then I’ll tell you,” I heard myself say, knowing we’d soon fizzle out. It was his turn to freeze with surprise. He couldn’t answer.

I couldn’t help but laugh. It made me think of my mom.