Illustration by Luc Melanson.

Illustration by Luc Melanson.

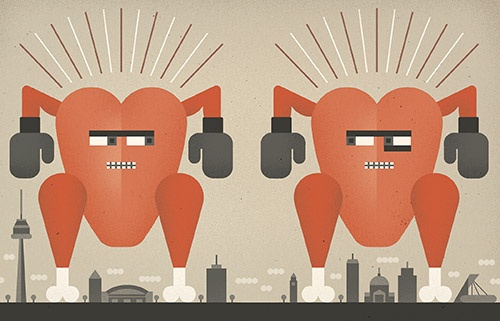

Comfort Feud

Canadians have a lot of cultural bones to pick, finds Denise Brunsdon, and maybe they like it that way.

This fall’s federal election revived concerns over national unity. The late-writ surge of the Bloc Québécois; Western Canada’s block of primarily Conservative MPs. The fractured nature of Canadian federalism was laid bare yet again.

Yet chicken aficionados surely weren’t surprised. Despite the last twenty years of national disunity denouement, they know that deep fractures have continued to simmer, grill and rôtissent. It’s obvious: Swiss Chalet and St-Hubert both specialize in rotisserie-style chicken dinner, yet one is Ontario-centric, the other almost exclusively limited to Quebec. And in British Columbia, White Spot dominates with its chicken burger, but has never ventured east of Alberta.

Just as one is not loosely affiliated with a province, neither is one loosely affiliated with one’s chicken. They don’t call it “eating your feelings” for nothing.

The first St-Hubert BBQ rotisserie chicken restaurant opened in Montreal in 1951 on St-Hubert St. The eatery was known in the early years for its free-of-charge delivery done by its fleet of yellow Volkswagen beetles. St-Hubert served its chicken on the grounds of Expo 67, expanding the franchise the same year to Quebec City.

The 1960s were a big decade in Quebec, and not just for chicken. Just one year after St-Hubert expanded to Quebec City, for example, the Parti Québécois was founded. That same year, 1968, a guy named Pierre Trudeau published a book of essays titled Federalism and the French Canadians, opining on the dangers of separatist rhetoric and the many reasons Quebec should stay in Canada. Though the book makes no direct reference to chicken, momentum for both separatism and St-Hubert continued to grow through the next several decades.

Today the franchise boasts 125 restaurants—all in Quebec except eleven of them, and even those are in New Brunswick or Franco-Ontarian communities near the Quebec border. St-Hubert once tried to expand to Toronto, but it didn’t last.

Sarah Biggs, a francophone who grew up in Montreal, remembers going to the local St-Hubert as a child in the 1980s and 1990s and fighting with her brother over the best buns. After moving to Ottawa as an adult, Biggs would make the effort to travel across the bridge into Gatineau to go to St-Hubert. And when she moved even further away—to Calgary, where she now lives—and before St-Hubert began widely selling its sauce, Biggs’ mom would mail her packets of it to make poutine.

A major part of the je ne sais quoi of St-Hubert’s aesthetic is the bird in its logo. Former Disney cartoonist Jack Dunham, who worked on both Fantasia and Snow White, designed it. The jovial, retro-looking cartoon rooster head is the third pillar in a triad of famous Quebec mascots, alongside Youppi and Bonhomme. The rooster is so famous that not only is its visage trademarked, its hair—the coif alone—is trademarked.

When asked, however, the chain’s devotees sometimes struggle to articulate exactly what keeps them loyal. At least until you ask about the alternatives. “St-Hubert is Québécois. It’s from home,” Biggs says. “I wouldn’t go and eat at Swiss Chalet in a million years.”

Swiss Chalet opened not long after St-Hubert, in 1954. And the plot thickened. Also a rotisserie chicken restaurant, the first location was in downtown Toronto on Bloor St. W. While Quebec was playing constitutional chicken, Ontario was eating chicken—lots of it. Swiss Chalet grew through the last half of the twentieth century to be the undisputed leader in the Canadian chicken scene, with a current total of 212 locations. But they’re primarily in English-speaking Canada, with the vast majority in Ontario. Fewer than a quarter are in Western Canada and there are none in Quebec.

However, things are not always as they seem. Swiss Chalet was founded by francophone Maurice Mauran, who was also from Montreal. To recap: Swiss Chalet has no connection with Switzerland. Yet it does have a connection with Quebec.

Krysten Milne, a young Toronto entrepreneur and marketing professional, has a plausible explanation as to why a Canadian restaurant chain would call itself Swiss Chalet. “Rather than simply serving a good meal, the company serves its customers a feeling of warmth and familiarity, which I would describe as similar to the feeling you get when you’re sitting by the fire in a ski chalet after a long day of hitting the slopes,” she says.

More than that, she suggested, Swiss Chalet combines this feeling of exotic fanciness with a low-key, unintimidating atmosphere. “I grew up in a small town in Ontario where dining options have always been fairly limited,” she says. “Swiss Chalet has been a staple there for as long as I can remember. In my experience, people flock there, pun intended, not only because they love the home-style comfort food, but because the restaurant has an ambiance that feels warm, cozy and familiar.” No Ontarian I spoke to would admit that calling it a “Swiss Chalet” is one way to just make it sound a little snobbier.

It’s fair to say that Quebec dislikes the chain. There used to be Swiss Chalets in Quebec, as far back as the 1950s, but the handful of remaining locations closed in the 2000s.Swiss Chalet’s parent company didn’t respond to a request for details on where they were or why they closed.

Still, it was conspicuous timing that the chain shut down its decades-long operations in Quebec in the years after the failed 1995 referendum, when support for the separatist movement began to wane. It’s as though the restaurant was a covert tether connecting the two provinces, a love letter from Ontario to Quebec stuffed inside roast chickens—a love letter that was never returned.

Or maybe Quebecers never even really considered adopting St-Hubert’s competitor; maybe Swiss Chalet’s main clientele was anglophone, and as that population dwindled, so did its faux-European chalets.

Most wars end at some point, and the longstanding rivalry between Swiss Chalet and St-Hubert is no exception. In 2016, Cara Foods (now called Recipe Unlimited), the owner of Swiss Chalet, purchased St-Hubert.

Ironically, the quasi-merger of the restaurants within the same corporate umbrella only emphasized the rivalry between the two. The disappointment reached the highest levels, with then-leader of the Parti Québécois, Pierre Karl Peladeau, calling it “a sad day for Quebec.” Montreal Gazette political cartoonist Terry Mosher went viral with his drawing of a nervous-looking St-Hubert rooster crying “MERDE!”

Canadians everywhere took to Twitter to declare their restaurant affiliation and slag the other camp’s food. Wrote the CBC’s Rosemary Barton (who attended a francophone university, albeit in Manitoba), “Do. Not. Mess w St Hubert sauce.” Sports broadcaster Gabriel Morency added that St-Hubert was a “much better product” and Swiss Chalet was “no doubt going to ruin them.” Yet culture writer Rebecca Alter fired back with, “Swiss Chalet buying St. Hubert is like when the stronger twin eats the weak shitty twin in the womb.”

People could only agree on one thing. As Andy Bowers put it—from the relatively neutral zone of Halifax—“Swiss Chalet & St Hubert are now one big happy family? Are you poulet my leg?”

As always, the West wants in. And White Spot has earned its way. The British Columbia-based restaurant chain is one of Canada’s oldest. Before St-Hubert, before Swiss Chalet, before WWII and even before the Great Depression, White Spot was founded in 1928, by a baseball player named Nat Bailey who turned his Model T into one of the original food trucks. The chain expanded to drive-in restaurants, and by 1960 it had ten locations, all in BC. There are now sixty-four locations: sixty-one in BC and three in Alberta. And of course, they source their chickens only from BC.

White Spot isn’t known today particularly for its chicken. When it started, however, its BBQ focus included a signature chicken sandwich. For a period, it even adopted a cartoon chicken for its logo, not unlike St-Hubert’s.

Lindsay Amantea, who was born and raised in Richmond, BC, recalls that White Spot was one of the only restaurants in the 1990s that provided every burger on the menu with either chicken or beef. Going there as a kid with her mom, the two would always order a burger to go, with sauce on the side to avoid the bun getting soggy, for her dad when he finished work.

However beloved it is in Western Canada, though, White Spot has never expanded past Alberta. Why not? Some might cite the widely publicized 1985 botulism outbreak from White Spot’s contaminated beef dip, which ended up with fifteen people hospitalized and five on respirators. But in the years since, White Spot has continued to grow—just always within the confines of the west.

Perhaps the chain is less bullish because British Columbians have been turning away from meat at a faster rate than the rest of Canada, with studies estimating that BC has the country’s highest per-capita rate of vegetarians and vegans. Or perhaps it’s just Western alienation, that quintessential devil-may-care attitude toward the Laurentian establishment as a metric for success.

Many successful Canadian brands remain regionalized: Jean Coutu in Quebec, Seaman’s soda on Prince Edward Island, London Drugs in the West. Stephen Heckbert, a public relations professor at Ottawa’s Algonquin College and a private-sector consultant in marketing, points out that not all Canadian companies are on a quest for countrywide domination; many are content to focus on a regional market. “It is only recently that we’ve begun to see more national brand presence, like Tim Hortons,” he says.

That regionalization is about more than geography, he says; it’s about the emotional connections Canadians build with companies from a young age, especially when it comes to food. “It is a lot about nostalgia. These are the restaurants that you went to as a kid, and that your parents took you to.”

Bitter conflict is nothing new to Canadian food critics. Lesley Chesterman grew up in Montreal and has been a food writer for over twenty years, including a long stint as the Montreal Gazette’s fine dining critic. She admits that while St-Hubert is the antithesis of fine dining, she has felt its irresistible pull. “If you analyze St-Hubert BBQ chicken, it’s not that good,” she says. “But I eat it all the time. When I was pregnant, it was my number-one craving. My kids are practically made of St-Hubert chicken—and that’s when I was in my die-hard food critic years.”

Canadians’ chicken allegiances are about nostalgia, she agrees, but it’s also undeniable that the country’s various regions have diverged in their cuisines and tastes.

“There is an absolute difference in palette between Quebec and the rest of Canada,” Chesterman says. “Even English people in Quebec have different taste than the French, just like they have different taste than French people from France.” Many Canadian foods are strictly associated with particular regions and essentially unknown outside them: cod tongues in Newfoundland, donair in Nova Scotia, hard oreilles de crisse (Christ’s ears) pork rinds at sugar shacks in Quebec, Doukhobor bread in Saskatchewan and bannock in Indigenous nations and Métis communities, especially in the West. Chesterman’s mother was from Winnipeg, and passed along to her Montréalais kids—who lived in maple syrup heartland—the back-home culinary tradition of corn syrup on pancakes. “I still love the taste of corn syrup on pancakes,” says Chesterman, “but nobody here would do that.”

None of this is genetic, of course—it’s all to do with the culture and flavours we’re raised with. “In the food world, food writers make such a big deal about the best lobster roll or the best cup of coffee,” Chesterman says, “but good luck getting people to change their habits. If St-Hubert changed two ingredients in their sauce, they would hear about it from customers within an hour… Whether one chicken or sauce is better is a moot point.”

That doesn’t stop the critics from trying. Chesterman herself says “the St-Hubert sauce is brilliant…the superior sauce.” But “if I had to say which chicken is better,” she adds, “I’d probably say Swiss Chalet.”

Toronto Star food writer Karon Liu says the chicken tastes more or less the same at both chains and it is the sauces that “get the debates going.” He notes a technical distinction that many ardent fans also point to. “The Chalet sauce is best known for its tanginess and darker colour, but keep in mind that they don’t call it a gravy but rather a ‘dipping sauce,’” Liu explains. “St-Hubert, meanwhile, does call their sauce ‘gravy’ and it tastes more like the standard nostalgic poutine gravy, like a very salty gravy made from a powdered mix that you’d find when you order poutine at the skating rink on a grade five winter field trip.”

Sauce is also key for customers. Biggs, for example, when asked why she dislikes Swiss Chalet, says matter-of-factly, “It’s the cinnamon in the sauce.” This allegation isn’t off-base. A Google search for “Swiss Chalet sauce recipe” returns over six hundred thousand hits, and many copycat recipes do include cinnamon.

Die-hard factionalists won’t be forced to branch out anytime soon, either, as most chains are making it easier and easier to stick to your own. St-Hubert sauce is for sale online these days at Walmart and Amazon. Swiss Chalet has also commercialized its sauce, selling it in grocery stores.

White Spot’s Triple-O sauce is a closely guarded trade secret, and the company likes it that way. Needless to say, it is not sold elsewhere. Amor de Cosmos, the notoriously eccentric former premier who advocated both for British Columbia to enter the federation, and then later to leave it, would be glad to see the spirit of rugged Western independence alive and well.

Maybe it’s for the best. Canada’s slightly more serious crises remain uncomfortable topics for most of us, from Quebec’s near-separation to modern-day “Wexit” anger. But one thing that unites most Canadians is our politesse and reluctance to confront others.

Luckily, we always have BBQ chicken. If you want to hear Canadians brag about their home province (or vent about other ones)—in coded, socially acceptable terms, of course—ask about the sauce.