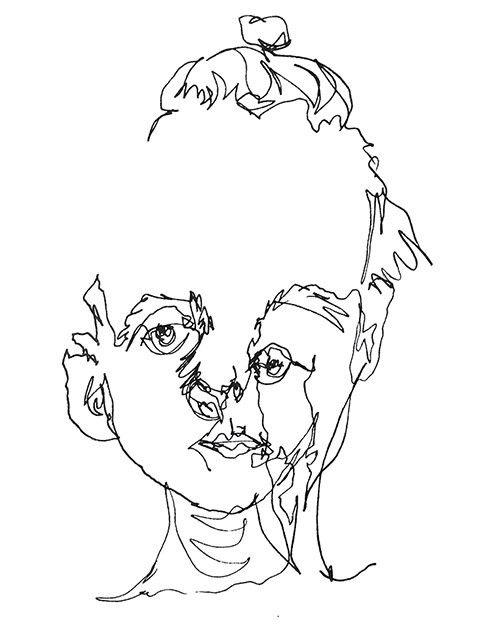

Illustration by Suzannah Showler.

Illustration by Suzannah Showler.

Face to Face

Holed up, Suzannah Showler asks what we really owe the outside world.

When Covid-19 sent the inessential among us home to stare down shapeless hours in private, I found I was, for once, ahead of the pack. As a writer, my days have been soft and solitary since long before now. Sometimes I think that what I secretly am is a Very Fancy Artist whose medium is time. You should see me work a day into shape all day.

Now, as people head online to document new rituals to assure themselves they exist, I feel both the sympathy and superiority of an early adopter. As for my own slate of ritualized self-assurance, it’s pretty full up, but I figure there’s always room for improvement.

And so, getting into the pandemic spirit, I pick up a drawing exercise suggested by a friend and string it into my daisy-chain of habitual behaviour. A lifelong dabbler, I’ve never been serious or regular about drawing, but now, every day, between coffee and sitting at my desk, I bring a sketchbook to the bathroom mirror to render my greasy, unsocialized mug.

The parameters: no looking at the page, keep your pen on the paper, a continuous line. The point of the exercise is to practice coordinating your hand and your eye, yoking movement to perception. This is, in its limited way, a form of self-sufficiency: achieving proportion without external reference. Truing like a wheel, getting right with yourself.

My hand strews across the page, unmoored, dragging out the space between clusters of features. The results are demented: hairline menacing overhead like a god, neck spewing from mouth, an eye listing off the edge of the face. You look how I feel.

I find these portraits comforting—an easy-access pass to metaphor, fixing me in place. I like writing the date at the top of the page every day. I like posting the results to Instagram, feeling like I’m joining in.

Making these portraits, I’ve found myself returning to the works of (bear with me) the twentieth-century French ethicist Emmanuel Levinas. Because for Levinas, the human face was everything. He staked his whole philosophy on it, describing the human condition as a state of infinite responsibility conjured by a face-to-face encounter:

In its expression, in its mortality, the face before me summons me, calls for me, begs for me, as if the invisible death that must be faced by the Other, pure otherness, separated, in some way, from any whole, were my business.

If this seems kind of intense, that’s because it is. Levinas is not fucking around. A face “calls me into question,” he says, making me “an accomplice” in someone else’s life and, ultimately, their death. We are here to implicate one another, to be one another’s calling. Other peoples’ faces are why we each exist. He writes:

Responsibility for the Other, for the naked face of the first individual to come along. A responsibility that goes beyond what I may or may not have done to the Other or whatever acts I may or may not have committed, as if I were devoted to the other man before being devoted to myself. Or more exactly, as if I had to answer for the other’s death even before being.

Like any good French philosopher worth his salt, Levinas is both lofting in poeticized abstraction while also being totally literal. He’s dealing in ideas about what it means to exist that can only be described in approximation, sentences that expand like an accordion. But he also means what he says: that we need to face one another in the world, to look at other people and see their innate vulnerability, their value, their need. Levinas says we each carry with us the inert, senseless tragedy of our own deaths, and it shows on our faces.

Levinas’s project is to put ethics—our responsibility to one another—first. In the process, he dismisses most philosophy as basically irresponsible and self-serving. There is a violence, he says, in such benign-seeming activities as thinking, contemplating, pursuing knowledge. I think therefore I am. All that’s really doing, Levinas would say, is grabbing the world, feeding it to the ego. It is, on some level, a belief that everything I encounter already belongs to me.

Levinas turns this on its head. He says we don’t think and therefore exist so that we can go about our lives and eventually ask what it is we owe to one another; we start out owing one another everything, and the very fact of our existence is a response to this debt. Levinas believes there is another way of being that precedes the knowledge-hungry, ego-feeding default we’re accustomed to. He is looking for an elusive state of passivity, openness and empathy. It’s hard to even find the language for it, he says. But it’s there.

In the grocery store, we follow arrows drawn on the floor in purple tape. These are the parameters for avoidance—the goal is to never cross someone’s path. I’m not well-organized, and it takes me four convoluted laps to do the shopping. I try to smile at other people over the produce, but we’re all wearing masks.

Levinas would say that the irrepressible vulnerability of the face is still present (“try to cover the face like a mask . . . but always the face shows through”). I’m not so sure. Is this eye contact coming off as solidarity and recognition, or are we just staring one another down, warning one another off? The checkout queue extends up the aisle, people bobbing apart like a line of buoys.

It’s a state of emergency, but for those of us lucky enough to be merely confined to our homes, the chaos is an abstraction—it manifests in daily life as minutia, repetition, containment. The hard part, I think, is mostly living with that disjunct—between what this feels like and what it means. Cause and effect are strung out, kept apart.

Indoors, life is compressed; outside, expansion is the dominant force. Bodies repel away from one another, pedestrians bounce one another off the sidewalk, as if the magnetic field of social life has shifted. We are too far spread out across a plane of view, and the dimensions are boggling. How, under these conditions, would anyone draw their lives to scale?

What I’m trying to say is that a pandemic is a state of emergency, but it’s also an aesthetic. Social distance isn’t just a set of rules—it’s a practice. There are parameters: measurements which add up to make a system. The results have a look, a feel.

And I’ll admit it, this part I am drawn to: that feeling of repetition, distance, a sense of purpose. Here I am, doing my part, joining in by dipping out. My way of being in the world has been validated, given a stamp not only of approval, but of necessity. We are all in this together, taking our loneliness and reimagining it as a duty. This is something I can work with. My responsibility to the Other is to stay the fuck away.

A point in Levinas’s favour: humans are so predisposed to faces that we conjure them where they don’t exist. The word for this is pareidolia: a perceptual error in which our brains organize random shapes into recognizable objects and bodies: man in the moon, constellations, Virgin Mary squatting piously in a block of cheese. On an Instagram account entitled Face in Things (bio: “Admit it, you see a face”) appliances look dismayed, root vegetables clutch one another erotically, butt-worn couches scowl. This is one way our brains make the world more legible and, often quite literally, more humane.

Almost everyone experiences pareidolia, but some are more prone than others. The inclination may or may not be associated with such qualities as religiosity, neurosis, and being female. Many studies say negative emotions lead to pareidolia—but one says a good mood will get you there. My question is: do we see faces in things because we’re looking for other people, or because we’re looking for replicas of ourselves?

If the impulse of pareidolia is to find meaningful objects in random shapes, one strategy for drawing portraits is to do the opposite: devolve what you recognize into its inchoate parts. Break everything down, break it apart.

Learning to draw faces means swallowing a contradiction. On the one hand, it helps to know some basics, internalize a rough idea of proportion. Failing that, most of us will make similar errors: features too large and too widespread (we tend not to notice that the human head is mostly skull). On the other hand, though, to make a portrait you have to forget what you know about faces and just draw that face—the one that’s right there looking at you.

As the days pass, my pandemic self-portraits seem more and more crucial to my life. Maybe it’s superficial, but converting my appearance into these scribbled lines makes me feel as if I’m learning something. Does getting to know the planes of my own face mean anything? Can I call this self-knowledge?

For the brief minutes that I’m drawing, I am pinned in time and space and also totally dissolved. And the skewed, uncanny results: these are the only strangers I really get a good look at anymore.

Instagram is an echo chamber. It feels good to bounce our containment off one another, see evidence of the new normal multiply and repeat. Everyone is trying to articulate the same, unfathomable things with this novel, limited vocabulary:

Sourdough starter bubbling and leavening in a jar,

a tiny society eating itself.

Selfie in homemade mask, cheerful cotton print.

Rows of Jiffy Cups, frail seedlings, future Covid gardens.

Faces in quadrants on a screen, a Greek chorus on Zoom.

Zoom everything: dance party, workout, worship.

Fragments of public space wrapped in yellow caution tape.

Irrepressible crocuses.

Messages is sidewalk chalk, signs in windows:

Be kind, we’re in this together, this too shall pass.

(Into what? I think every time)

Downtown, a hotel flicks on lights in empty rooms, drawing a heart on its facade. This is in the city where I live, but I only see the image on Instagram.

In other cities, they’re quick to turn hotels into shelters. Here in Nova Scotia, the premier shows up on TV every day to audition for the role of Pissed-Off Dad. He’s committed. Let’s call it: method. I think he kind of likes it, honestly: getting to say who’s being irresponsible, who’s doing this pandemic wrong.

Okay, now we’ve done it, now he’s really mad: Stay the blazes home. So folksy! So righteous! Charmed, I’m sure. His outburst is autotuned and remixed as down-tempo hip-hop, covered as a folk song, emblazoned on a $35 T-shirt, a $15 mug, proceeds to charity, something worthy, so now we can feel fine about it. The memes are so quick they seem like they might have predicted the moment rather than followed it.

It’s early April, three weeks in. What would he give us if not a scolding? Maybe: ban all evictions, freeze rent, drop the cost of power. Maybe reimagine what the emptiness could be—who or what it could accommodate. You can’t just yell at everyone to stay home without bothering to ask the obvious: Where is that? What does it feel like to be there? What do you have? What do you need?

“An ideal, a collective representation, a common enemy will reunite individuals who cannot touch or endure one another,” Levinas writes. There is something despairing about it, he says—how we come up with abstractions to bring us together when we are unable to form a community face-to-face.

Levinas knew some things about enemies, reunion, endurance. He joined the French army as a soldier and translator, was captured and spent most of WWII in a POW camp. In fact, Levinas, who was Jewish, didn’t wind up in a concentration camp only because the Nazis, oddly enough, upheld the Geneva Convention on prisoners of war. Many of Levinas’s family members—his father, brothers, and mother-in-law—died in the Holocaust. His wife and daughter managed to survive in no small part thanks to philosopher Maurice Blanchot, who helped them shelter in a monastery when the German army invaded France.

Much of Levinas’s work on ethics came after the war, and he even began some of it as notes while he was a prisoner. The crux of his thought should be read with this in mind: the saturation of mortality, all those faces of strangers and neighbours exuding need. The biographical context feels useful to me not only because it helps clarify what Levinas is saying, but because it makes me feel a little bit less absurd for turning to abstraction in a difficult moment. I don’t want to suggest any kind of equivalence between Covid-19 and the Holocaust, obviously. I’m only saying that Levinas provides a reminder: philosophy can sometimes come out of experience; it’s not always the other way around.

If Levinas makes for good pandemic reading, it’s because he’s always navigating a tension between proximity and distance, trying to articulate exactly how close we need to be to other people. It is my neighbour—the Other closest to me—to whom I owe the most, he suggests. And yet we also need to resist the urge towards over-identification, feeling responsible for others only when it serves our sense of self. His ideal is solidarity articulated through distance. There is, he writes, “a fraternity existing in extreme separation.”

The other person’s face is literal. It will arrive—it will call to you, needing something you have. But it’s also an idea: a thing to remember when there’s no one there to remind you that your very existence is a debt. “To be one’s brother’s keeper is to be his hostage.”

Slush falls from the sky, like the day couldn’t decide between freezing and soaking, had to try for both. A woman appears, cutting a line down the middle of the road, screaming and sobbing. I go to the door with my stupid question: Are you okay? She asks for a ride, names a place I don’t recognize. It’s a shelter, she has to tell me.

I urge her to the porch but don’t invite her in, upholding the mandated distance. I’m disoriented by it. I feel like shit. I’m sorry, I say, I would, but—

She’s wearing an electric pink Baja hoodie, and she’s drenched. I try not to notice her cough, how she catches it in her hands. I ask for her name. Stay there, I make her promise. Which means don’t leave, but also: don’t come any closer.

I don’t have a car, so I call a cab and hunt for cash, find $5 and a peeling $10 bill I put back together with masking tape. I fill the largest mug in the house with water and bring it to the porch. This distance I’ve quilted around me, built up over days of telling myself it was right and good, has to dissolve for me to hand it over. Her hands are bright with cold, bare, unwashed. I can’t stop making calculations. She drinks the water and passes it back. I take it to refill, thinking about contamination, aware of every surface. I give her a pair of dollar store winter gloves.

I keep returning to the doorway, eyeballing distance, calling offers into the void: tea, coffee, food. I’m celiac, she says. We don’t use gluten! I say like it’s an accomplishment. I bring a Larabar and a banana. This starts to feel like a perverse ritual: approaching the threshold, leaving offerings, retreating, closing the door on her each time I go away. Don’t leave, I repeat. I’m not.

The cab is slow. Please, please, please, the woman moans. I tell her it’s OK, though clearly it’s not my call. I tell her the cab will be here soon, though what do I know. I pretend I’m waiting with her, but I’m inside the doorway, and she’s on the open porch, under the weather. Not one line of small talk I come up with makes sense.

How are you? I ask. Terrible. Right, duh. I apologize again for not inviting her in. Bless your sweet heart, she says, and I find the wording unnerving—earnest religiousness kind of freaks me out. Do you have any more money? I don’t. I’m not even sure the cab will take the shoddy taped-up $10 I’ve already come up with for its brokenness, its contaminants, both.

We run out of talk, and for a while we just stand there looking at each other from six feet apart. I find myself nodding for no reason. Her face is round, young, freckled. Mascara bolts from her eye to her lip. She cries until the cab comes.

Another day, another drawing: trying to locate the face in my face, find the familiar in the strange, the strange in the familiar. And repeat.

Pareidolia is considered a subset of apophenia: the tendency to impose order where there isn’t any, to find meaning in random data or stimulus. This is a concept so capacious I have a hard time understanding how it’s even a thing. Like, what distinguishes this from the basic metabolic function of consciousness? What is thinking, existing, moving through time if not imposing sense where it doesn’t naturally exist? We take what we get and reorganize it into something we can work with. I don’t think I can conjure a mode of existence that precedes that. If I did, I’d just dissolve.

And the woman in the street whose call I answer, whose business I make mine? I know what I’m doing: making an anecdote of the person who ruptures my solitude, whose need momentarily forces me to close a gap, reconfigure the spatial dimensions of my sense of duty. My distance was right and good until it wasn’t.

I don’t kid myself—I know who I am. My choices, as usual, are only aesthetic. I’m shovelling the world into my mouth, claiming it as knowledge. I’m telling a story because on some level, I think it all belongs to me.

A few days later, a coin flips and it’s the other side of spring: flush, sunny, possible. My partner and I are out walking—this is what we all do now, pacing our neighbourhoods in circles—when I see her coming up the block. She recognizes me sooner than I expect her to, lifts her hand and shouts hi. In the new weather she is transformed: I didn’t notice the first time that her hair is red, wavy in a careless way there are YouTube tutorials for. She’s walking with another woman, and we pass in courtly pairs, arms linked, circling the bubble of propriety in a slow, tame do-si-do. How are you? I ask. Hungry, she says.

The next week, the weather is shit again, and there’s sobbing in the street. A bolt of pink wool. I duck and hide, crouch below the window, burrowing. This is my greatest luxury: choosing shame. I peek up and watch her walk away from me across the empty street, heading towards the gas station, screaming for no one.