The Winter 2021 Book Room

Winter reads from Tara McGowan-Ross, Isabella Wang, Helen Chau Bradley, and others.

Nothing Will Be Different

Tara McGowan-Ross thinks she’s going to die. She’s twenty-seven years old and finds a lump in her left breast. In Nothing Will Be Different (Dundurn Press), she weaves together a narrative that’s not only about herself, but also capitalism, colonialism and all the other isms that have shaped her identity. The memoir is honest and raw, but also deeply funny in its portrayal of grief, mental illness and addiction. McGowan-Ross’s background as a poet is clear: “I will fight so hard to make it look like I’m changing,” she writes. “I will fight so hard to keep things exactly the same.” She often invokes the reader throughout the book, as though she’s telling a story to a friend. “I have to back up a bit, here, again. Bear with me,” she writes in a moving chapter about the day she receives her status papers. Her boyfriend has just broken up with her and she’s doing poorly at work, but her father arrives with a bouquet of roses and good news. Nothing will be different, but McGowan-Ross also leaves a little room for hope that things can change.—Sara Hashemi

Pebble Swing

Family can be the source of both comfort and pain. Isabella Wang plays with the entanglement of these two seemingly opposing sensations throughout her debut poetry collection Pebble Swing (Harbour Publishing), exploring her own family history and meditating on a sense of home. In “Redemption,” she shares the story of her great-grandmother fruitlessly trying to console her father as an infant: “She tried rocking him / beating him.” In “Occupational Hazard,” she writes of her father as an adult: “I know you never liked the taste / of alcohol, but to put a roof over the idea / of your future daughter, you chose / an occupation that required you to drink.” Wang finds tenderness in the ugly, at times violent, realities of love and family. Grappling with losing her mother tongue, Wang looks to the literary past through poets like Phyllis Webb and Joe Brainard in order to extrapolate and reconstruct her family’s collective memories, turning them into something entirely her own. Pebble Swing embroiders a plurality of histories, cultures, languages and legacies into something singular. —Allegra Moyle

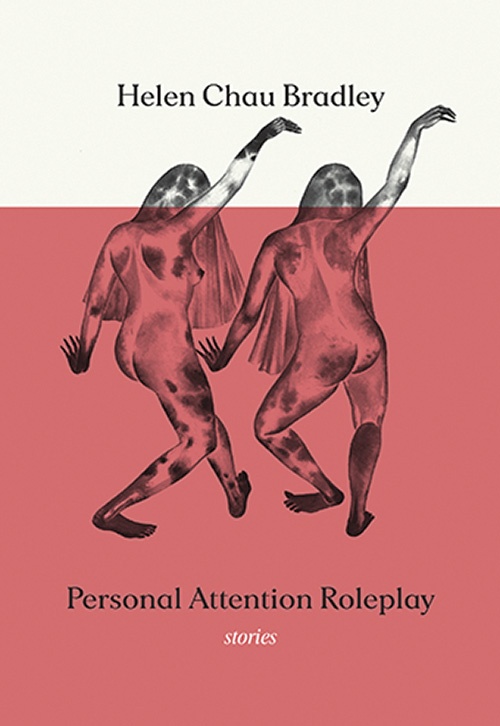

Personal Attention Roleplay

Helen Chau Bradley’s debut collection consists of ten carefully crafted narratives about unrequited queer crushes and questions around identity and intimacy. The characters in Personal Attention Roleplay (Metonymy Press) wrestle with jealousy and loneliness as they navigate their own messy attempts to “see and be seen.” Chau Bradley’s writing is evocative. Unexpected odours, shapes and sounds constellate each narrative, like the writhing maggots in the titular story that “arrang[e] themselves into a face” to speak in their “squelching collective voice.” The book is also funny; in “The Queue,” a text that draws inspiration from Russian novelist Vladimir Sorokin, Chau Bradley tells a pandemic story in unattributed dialogue, which includes chants for “toilet paper now!” alongside “fuck la police!” Personal Attention Roleplay explores, above all, a wide range of perspectives. Notably, “Soft Shoulder” is a “we” voice narrative from the point of view of a queer metal band. It’s a remarkable revenge tale that tackles toxic masculinity in the music scene, while interrogating what it means to be complicit in harm. Like anything Chau Bradley creates, it’s clever and complex.—Angelina Mazza

Special Topics in Being a Human

Caring for ourselves and the people around us isn’t easy, especially during a pandemic. Thankfully, Internet dad and advice columnist S. Bear Bergman is here to guide us through it. Special Topics in Being a Human (Arsenal Pulp Press) offers a blueprint for navigating difficult conversations and tricky situations, from breaking stressful news gracefully to distinguishing criticism from insults. Illustrator Saul Freedman-Lawson’s subtle yet detailed drawings of people and the situations they face complement Bergman’s advice nicely. In chapters such as “How to Keep Going When You Just Want More Than Anything to Stop, for G-d’s Sake,” Bergman shares witty, compassionate wisdom: “Pretend your motivation is a three-year-old already having a hard day. You need it to keep going a little longer and not completely wilt (and then require carrying). Be gentle.” He brings the same thoughtfulness to sections on pronouns, allyship and support for people of marginalized genders. Amid the chaos of everyday life, Special Topics feels like a hug—a soft reminder of all the good there is around and within us, or, at the very least, of all of us striving towards it.—Tobin Ng

Because Venus Crossed an Alpine Violet on the Day that I Was Born

Revelling in nostalgia can feel like the warm embrace of a familiar friend. Yet linger too long, and it can hold you back from finding yourself. In Because Venus Crossed an Alpine Violet on the Day that I Was Born (Book*hug), Norwegian author Mona Høvring explores that complicated nature of nostalgia (translated by Kari Dickson and Rachel Rankin). The novel is slim, its plot neatly contained and fast-moving. In a quaint mountain village hotel, grown sisters Ella and Martha attempt to reconnect when Martha returns home from a stay in a psychiatric hospital. Høvring writes with a keen eye for atmosphere—descriptions of the cold winter air around the hotel mirror the emotional chilliness between the sisters. When a seemingly innocuous argument prompts Martha to disappear in a fury, Ella is forced to reckon with her emotional dependency on her complicated older sister. “You can think you’re in love when you’re only really clinging to memories,” reads a passage from a book Ella discovers in the hours after Martha leaves, signalling that the time has come to forge her own identity. —Madalyn Howitt