Photographs by Kitra Cahana

Photographs by Kitra Cahana

Against the Clock

Time restraints in long-term care homes create tension for residents and workers. Jackie Brown and Leanna Katz consider alternative ways to structure their days.

It’s 1:30 PM when Michelle arrives for her shift as a personal support worker (PSW) at a long-term care home in Southeastern Ontario. She doesn’t clock in until 2 PM, but the extra thirty minutes buys her time to get updates from the staff on duty. Has anyone fallen, had their meds changed, or not had a bowel movement in a few days?

When her shift begins, the tempo picks up. She prepares her cart, stacking it high with folded towels and fresh bedding, and checks the binder with her schedule for the evening. Her eight-hour shift is broken down into blocks of time: resident care, dinner, bedtime preparation, evening snack, charting. It often feels like a race to bathe one or two residents and wake others from their afternoon naps before the dining room doors open at 4:30 PM.

At dinner, Michelle feeds one resident while coaxing another to eat as she nods off (sleeping through dinner is not a problem in itself, save for the fact that the resident is diabetic and especially requires regular meals). Afterward, some people watch television in the sitting room, but quite a few go straight to bed, even though it’s only 6:15 PM. For many residents, the days drag on—interspersed with playing bingo or folding laundry—and they can feel endless. For PSWs, however, long-term care is an exceptionally fast-paced environment. As Michelle puts it, “You’re always go-go-go.”

Over 184,000 people in Canada live in long-term care homes. Much of the frontline work is performed by PSWs who assist elderly residents with the activities of daily living. Their jobs are vital to residents’ health and wellbeing, yet Ontario PSWs are paid an average of just $22.69 per hour. PSWs are disproportionately women, visible minorities and immigrants, and thus often face barriers, such as education, language and their own caretaking responsibilities, to accessing higher-paid work. Despite the growth in demand for long-term care given Canada’s aging population, there is a lack of full-time employment in the field. Many PSWs work multiple part-time jobs to earn a living.

The work is stressful, heightened by the difficulty of providing end-of-life care. PSWs also face a high risk of physical injury from tasks like lifting people with mobility challenges, as well as aggression and violence from agitated residents. “I have lots of bruises on my body from being punched and kicked. I’ve been bitten. I’ve been headbutted, slapped, you name it,” Michelle says. She doesn’t blame the residents, many of whom have cognitive impairments, but it makes the job harder.

Burnout is widespread. According to a 2020 staffing study by the Ontario government, about 25 percent of PSWs in Ontario with two or more years of experience leave the long-term care sector each year—that’s a quarter of experienced workers exiting annually. Underinvestment in care creates a cyclical problem: PSWs are short on time, leading to workplace injuries and stress, and the weight of demands in turn contributes to burnout and high turnover.

Staffing shortages also compromise quality of care. When PSWs are pressed for time, residents miss out on baths and washroom trips, and are forced to wait to have their basic care needs met. In a 2006 survey of PSWs in Canada, nearly half of respondents reported working short-staffed on a daily basis. The fact that short-staffing continues to be a major issue indicates that it isn’t a temporary blip; rather, it is built into the business model of long-term care. PSWs often express a desire to sit and chat with residents, but say they do not have nearly enough time for the relational aspects of the job.

Michelle (a pseudonym to protect her from any possible fallout for sharing about her work) has been employed at the same long-term care home for nearly five years. Before that, she ran a home daycare. She says a striking difference is that saying goodbye to little ones meant they were taking their next life step, whereas saying goodbye to seniors means something very different. She nevertheless loves her current job—she feels it’s a privilege to care for those who are dying. But lack of time interferes with giving residents the attention they deserve.

Michelle’s heavy workload means she is constantly assessing and prioritizing needs according to the degree of urgency. When one resident wants to go to bed right after dinner, Michelle promises to help her after she escorts others out of the dining room. Not two minutes later, the call bell tolls—the same resident rings for assistance. Michelle pops her head in to say she will be back shortly, then rushes back to close out the meal. Residents often grab her hand as she leaves, not wanting her to go. For Michelle, this can be painful. While she wants to spend more time with each person, she can’t abandon others waiting for her to address their basic needs.

The experience of waiting is all too common for residents—waiting to use the bathroom, waiting to be served their meals, and waiting for opportunities to enjoy a more engaged experience of time. As Thomas Mann writes in The Magic Mountain, a novel set amid the monotony of daily life in a tuberculosis sanatorium, waiting “means regarding time and the present moment not as a boon, but an obstruction.”

Time is an undercurrent that shapes our lives. It is at once a subjective experience, which may speed up when we feel joy or slow down with sadness or boredom, and an objective unit of measurement to which we affix a monetary value. In long-term care, there is a rift between the time PSWs require to provide residents with quality care and the time they are actually afforded to complete this work. Taking time as a starting point, is it possible to achieve greater harmony between the care seniors need and the resources staff receive to do their jobs?

In 2017, Unifor, a union representing thousands of long-term care workers, challenged members of the public to perform their morning routine in six minutes—the approximate amount of time the union says PSWs have to get residents ready for breakfast each day. This time needs to cover helping them get out of bed, use the bathroom, get dressed, and brush their hair and teeth. The initiative was an effort to raise awareness about time pressures in long-term care. Most people who attempted the challenge found it impossible to get everything done in the allotted window, perhaps managing to rinse their face and throw on some clothes, but not much else.

In a 2013 study of time use in long-term care, researchers from the University of Victoria and the University of Alberta found that healthcare aides’ time was frequently fragmented into one, two and three-minute activities. Social interactions between staff and residents, to the extent that they occurred, were typically restricted to moments when the aide was performing a task. At its worst, long-term care has been characterized by PSWs and advocates as “assembly-line care,” a reference to the warping of acts of care into items to tick off a checklist.

The situation worsened with the pandemic, which devastated long-term care homes across Canada. During the first wave, outbreaks swept through nearly one in three homes. Restrictions imposed in most provinces to curb the spread of the virus meant residents could not receive visitors and were isolated in their rooms for extended periods. In the home where Michelle works, nearly thirty residents died of Covid-19 in just two months. Once, three people passed away in a single shift.

The day before one of our conversations, a resident who had been experiencing minor difficulty breathing unexpectedly passed away. Emotionally, Michelle says, the pandemic has been one of the most difficult periods of her life, and she’s had to steel herself to get through each shift. During the early waves, after someone died, Michelle and her fellow workers would sometimes huddle together, taking a moment to grieve in one another’s company before returning to work.

The frequency of death at the height of the pandemic created an emergency with its own particularly urgent sense of time. “In an emergency, there is no time, except the time of now, a time that is running out,” notes cultural-political geographer Ben Anderson. Despite the intensity, Michelle felt her shifts were elongated, owing in part to the emotional heaviness of mounting deaths and the banal repetition of donning a gown and PPE each time she entered a resident’s room. In rupturing the familiar, emergencies reveal the “everyday” time that existed before, and to which we expect to return. Even pre-Covid, however, underfunding and understaffing had created a chronic crisis in long-term care, which contributed to the sector’s vulnerability to the pandemic.

The cruel irony is that because of the number of people who died of Covid-19, Michelle had more time to spend with each resident. (The spots left by residents who passed away were not immediately filled by new people, perhaps due to provincial directives against three and four-bed ward rooms.) Michelle says the additional time—about five extra minutes with each resident every shift—allowed for more fulfilling conversations. “Doesn’t sound like much,” she says. “But in long-term care, five minutes, it’s a long time.”

How did elder care come to be dictated by fixed intervals of minutes, rather than the specific tempo of individual needs? The history of time measurement sheds light on how our experience of time has come to be governed by the technologies invented to track it.

For thousands of years, the cycle of sunrise and sunset shaped the daily rhythms of individual and communal life. Ancient Egyptians built some of the first instruments to measure time, including sundials, which split the day into hours, and water clocks, which measured even smaller units of time.

Clock towers started popping up in public spaces in medieval Europe. The invention of the spring-driven clock in the fifteenth century permitted the manufacture of portable clocks and watches (some credit German locksmith Peter Henlein as the maker of the first watch, while others argue that it likely occurred contemporaneously in various places). Clock towers allowed more widespread public awareness of precise time, while portable timekeeping devices did the same for individuals.

Both developments helped usher in an era of standard and uniform timekeeping. Writing in 1967, English historian E.P. Thompson professed that in the seventeenth century the clock “engrossed the universe,” and by the middle of the eighteenth century it “penetrated to more intimate levels.”

As the Industrial Revolution swept through England in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, it established what Thompson described as an industrial time sense. Unlike in agrarian societies, where daylight and seasons shaped work patterns, industrial modes of production relied on synchronized working time to efficiently coordinate processes via the division of labour.

A worker’s time became commensurable with an employer’s money. Clocks, bells, timesheets and fines for tardiness were all used as tools to discipline and surveil workers’ time in the name of maximizing productivity. With the transition to industrial time, workers experienced a distinction between their employer’s time and their own time, and consequently, a greater divide between “work” and “life.”

This division was accompanied by a culture of time poverty, perhaps most entrenched by American mechanical engineer Frederick Winslow Taylor. In 1881, Taylor began running time-motion studies to calculate how to shave seconds and minutes off of workers’ tasks on the shop floor. In one example, he recorded thousands of stopwatch observations of workers testing different shovel types and body motions to optimize shovelling speed. Efficiency qua time scarcity was etched not only into industrial work, but also into homemaking and leisure.

International and domestic laws standardized a model of working time based on arrangements common in the Industrial era. In 1919, the first convention of the International Labour Organization regulated working hours. In 1944, Ontario capped the workday in certain industries. Today, the rise of the gig economy means that the eight-hour workday and forty-hour work week are less dominant, while workers in all fields log upward of sixty or eighty hours per week. Despite these changes, Industrial-era work arrangements left an imprint on our cultural understanding of working time.

A widely held image underpinned assumptions about standardized working time—that of a male breadwinner with full-time, long-term employment who earned a family wage and supported a female caregiver’s unpaid labour. This view treats women’s “reproductive” labour (including activities related to health, care and education) as removed from productive work in the market, despite the fact that reproductive labour enables labour market participation. Today, care work has been subsumed into the economy and, as a result, it is saddled with both market pressures and the contradictory belief that it does not merit adequate compensation or decent work conditions.

Historically, many families cared for seniors at home. Charitable and municipal institutions, as well as private facilities, emerged to care for those who could not support themselves, including the elderly. At present, long-term care homes are owned by a mix of public, nonprofit and for-profit entities. Large chains have proliferated in some provinces over the last several decades, fuelled by policies that favour providers that already have significant access to capital, and by their ability to leverage economies of scale to manage complex bidding processes and regulatory burdens.

As of 2021, nearly one-third of Canada’s 2,076 long-term care homes had for-profit ownership. This proportion is highest in Ontario, at 57 percent of homes. The provincial government subsidizes all long-term care homes, but licensing and funding for new home construction often privileges for-profits. Yet studies show the private sector generally has lower staffing levels and has had higher mortality rates during the pandemic.

In the shared space of long-term care homes, there are at least two distinct rhythms arising from the confluence of market pressures and assumptions about work and care. On one hand, the hurried pace of workers’ time, pegged to an assigned monetary value; on the other, the slower cadence of residents’ time. The space is both a workplace and a home. And the convergence of PSWs, progressing from task to task in a somewhat linear fashion, and residents, locked in the repetition of days and nights as teams of workers rotate in and out, creates some tension.

French philosopher Henri Lefebvre argued in his book Rhythmanalysis that a given space is a product of the rhythm of daily life, and the body is a place where natural and social rhythms interact. In Lefebvre’s view, external homogeneous time measurement imposes itself on the internal experience of time. We experience the ebb and flow in bodily cycles of hunger and satiation, sleep and wakefulness—but in long-term care, the body’s rhythm is modulated by the institution’s schedule.

Residents’ memory challenges further complexify the experience of time in long-term care homes. The Canadian Institute for Health Information reported that 69 percent of long-term care home residents had dementia in 2016, and up to 87 percent had some form of cognitive impairment. During bedtime, residents with dementia often revert to childhood, and Michelle notes that many ask after their parents.

Time travel, the experience of reliving past events, is central to human memory, but people with memory impairment are limited in their abilities to acquire new memories or retrieve stored ones. They may believe they are living in an earlier period of life or confuse the past with the present. As a result, they can feel stuck in time, isolated and disconnected from those around them.

Researchers in Norway who studied how people with dementia experience time point to “sovereign time rhythms” as a way forward. This means empowering workers with the flexibility to spend their time according to their view of good care—conversing with residents, feeling present in interactions rather than distracted by demands, and meeting residents where they are in time. This mode of time prioritizes the relationship between workers and residents, rather than a schedule tied to the clock.

For years, advocates have called for policy changes requiring long-term care homes to provide residents with at least four hours of direct care per day, supported by research dating back to a 2001 report to the US Congress that analyzed minimum staffing thresholds. In 2018, the Ontario NDP proposed the Time to Care Act to establish such a baseline. The bill recommended calculating the four-hour standard at the level of individual facilities, with each home in the province expected to provide an average of four hours of nursing and personal support services to residents.

At the bill’s second reading in 2020, its sponsor, MPP Teresa Armstrong, shared a story from a local PSW to highlight the loss of dignity to both residents and workers when workers’ time is in short supply: “Our residents deserve better than to be told, ‘I’m sorry, you have to wait to use the bathroom,’ ‘I’m sorry, you have to wait to get up or lie down,’ or ‘I’m sorry, I don’t have time to talk right now,’ even though that’s what the resident needs at that point in time.” The NDP’s bill stalled in committee after second reading.

More recently, Ontario’s PC Party passed the 2021 Fixing Long-Term Care Act, following public outcry in response to the pandemic. The new legislation sets a target of four hours of direct care per resident per day—crucially, however, this is to be calculated as an average across all homes in the province, rather than per home. As a result, some critics worry that for-profit facilities, which already provide fewer hours of care than non-profit and municipal homes, will not be held accountable for failing to meet the minimum standard.

Many provinces and territories do not legislate minimum hours of care. For those that do, the minimum staffing standard or suggested guideline is typically less than four hours. Manitoba, for example, requires 3.6 hours of care per day, while British Columbia recommends 3.36 hours. However, homes continue to fall short of these benchmarks (though the proportion of homes meeting the guideline in British Columbia has steadily increased over the last several years).

In her book The Political Value of Time, political scientist Elizabeth F. Cohen observes that time can serve as a proxy for legislative goals. The duration of a criminal sentence, for example, purports to stand for the length of the punishment or the time considered necessary for rehabilitation. A voting age conveys a minimum expected maturity to participate in the political process.

However, Cohen points out that time-based criteria are often motivated by underlying values—and their impact depends on how a given time requirement is measured. In the case of long-term care, the difference between calculating the four hours as an average per home versus an average across the province may affect the quality of care residents at the margins receive.

Why denominate reform in the currency of time rather than, for example, higher wages or better worker-resident ratios? More time for direct care requires systemic investment. Michelle explains that the four-hour standard can’t be achieved without more staff, but there aren’t enough interested candidates. Higher wages, better benefits, expanded education and training, and more communication around workplace issues are vital to achieving both decent work conditions and higher-quality care.

In theory, at least, PSWs’ interest in better work conditions would seem to align with better resident care. But when PSWs’ time is made into a scarce resource, they may opt for efficient ways of completing tasks at the expense of involving residents in basic decisions. Instead of asking residents what they want to wear, Michelle’s co-workers pick out their clothes to speed up the process. If residents want to sit outside, they sometimes must wait until a “life enrichment” staff member is available to supervise.

Michelle’s ideal vision for long-term care would drastically increase the staffing ratio so that workers could spend more time with residents, especially new residents who are adjusting to the environment. She would provide healthier meals and redesign the rooms—big, bright bedrooms with bathrooms large enough to comfortably fit residents’ wheelchairs. Each home would have as many PSWs as required to address people’s physical and social needs, a change that Michelle says starts with better compensation. These changes would help cultivate a more humane rhythm of work and life in long-term care.

Faced with a gulf between clock time and the rhythms of human needs, it may be time for a revolution in the clock, or at least our use of it. The rift between clock time and our subjective experience of it is captured by the work of modernist authors. As Virginia Woolf writes in Orlando: “An hour, once it lodges in the queer element of the human spirit, may be stretched to fifty or a hundred times its clock length.” Time can be compressed, expanded, and twisted, and two people in the same physical space can inhabit an entirely different lived sense of time.

Yet William Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury warns of becoming subservient to measured time. When the character Quentin receives his grandfather’s watch from his father, the gift is accompanied by the discerning advice: “I give it to you not that you may remember time, but that you might forget it now and then for a moment and not spend all your breath trying to conquer it.”

The pandemic has invited a moment of reckoning with how we spend our time. In order to elevate values like human connection, care, and dignity, we need to invest our time accordingly. Investing in care would allow for more shared moments of connection.

After dinner, Michelle spends most of her shift putting residents to bed. She enjoys this part of her job—it’s part of why she chooses to work evenings, though there are stressful moments. As it grows dark outside and shadows emerge, residents with dementia sometimes experience “sundowning,” behavioural changes including confusion, aggression and hallucinations. Still, Michelle can steal a few moments to chat with them or enjoy their presence while changing them into their pyjamas and tucking them in for the night.

Michelle and her fellow PSWs sometimes sing to one resident as they transfer her from her wheelchair into bed. This resident has trouble communicating and it’s unclear how much she understands, but her face lights up whenever Michelle starts speaking to her. Once she’s in bed, Michelle pulls up the covers, turns off the lights and says goodnight. ⁂

Jackie Brown is a researcher and journalist interested in new possibilities for housing, work and care. She studies political economy with a focus on financialization.

Leanna Katz is a lawyer and writer interested in how the law can contribute to improving work and welfare.

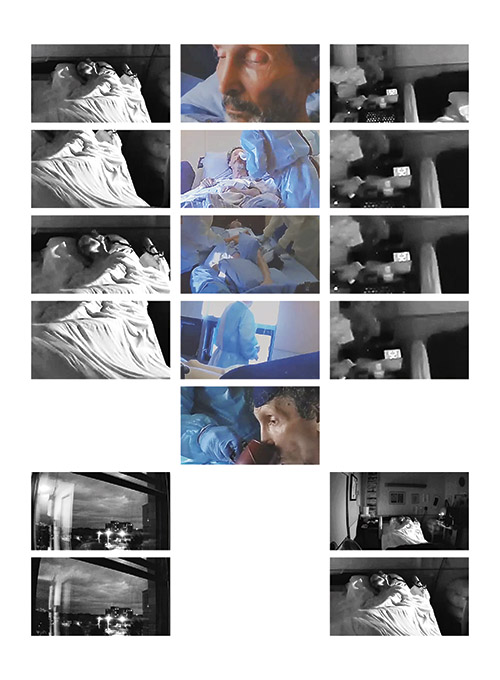

About the art: The images shown here are frames from filmmaker Kitra Cahana’s short documentary Perfecting the Art of Longing (2021). Filmed remotely during the pandemic, Cahana captured her father’s experience in a long-term care facility through lockdown. The film features this quadriplegic rabbi’s reflections on love, hope and what it means to be alive in a state of profound isolation. Cahana's film can be viewed on the NFB website.