Art by Eunice Luk

Art by Eunice Luk

The Path Forward

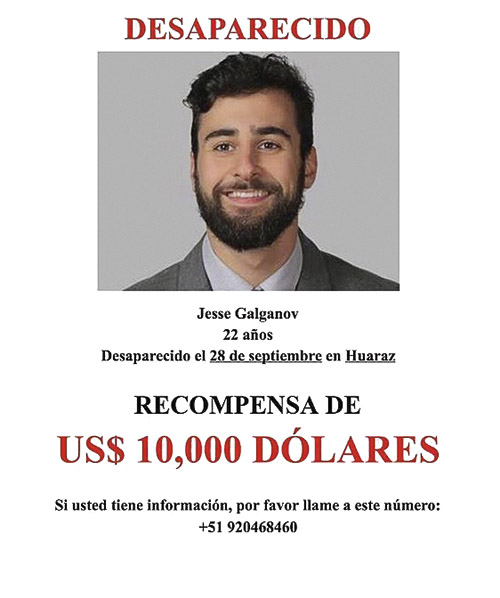

Jesse Galganov disappeared while backpacking in Peru nearly five years ago. When a friend goes missing, writes Ben Libman, there’s both everything and nothing to do about it.

It begins like this. You return home one Saturday afternoon in October, the leaves on the trees in Central Park barely bronzed, and recline on the sofa by the window, tea in hand, to read through your social media accounts. On Facebook, a friend of yours has shared the post of another friend: Hi guys! I’m reaching out to see if anyone has heard from my good buddy, X, in the last three weeks. If you have, please message me. Thanks !!

You sit up, spilling some tea into your lap. When was the last time you spoke with X, actually? Recently, you’re sure. You look through your DMs, your emails, your texts, your Snaps, and remember, as a nauseous feeling grips your abdomen, that the last time was one week before he went on his trip to South America. Four weeks ago, then. You had just arrived at the Montreal bar where you would grab a drink for the last time before he left for a year. Sitting at a wonky table, you had sent him a DM: Where are you?

You’re standing now. You call the friend who shared the Facebook post. His name is Julien. “What’s going on?” you ask him, or something roughly equivalent. Julien seems almost incapable of getting the right words out, repeating how “crazy” and “fucked” the situation is. He tells you that Jesse—for that is X’s real name—hasn’t been heard from since September 28. You look at your watch, the tiny square with the date reads 14. Your next thought is to ask about Jesse’s mother, Alisa, whether she has heard anything. “Why do you think I shared the post?” he asks, meaning, of course, that Alisa was the first to raise concerns.

Julien explains, as you yourself vaguely know, that Jesse began a five-day-long hike in Peru on September 28. He assured Alisa, on that day, that though he would not have service he would be reachable again on October 2. “So, twelve days since then,” you say, hearing your own banality roll through cellular space like a tumbleweed. There is a long pause, during which you think that this is an overreaction. A public Facebook post?

You imagine Jesse, emerging from the Peruvian mountains with a couple of new friends and some sylvan souvenirs stuffed in his pockets, startled and upset to learn that back home, his entire community has been needlessly (and embarrassingly) flooded with the news of his so-called disappearance. During this long pause, you think that not only is this lapse in communication not bizarre or worrisome, but that it was probably even to be anticipated.

But then if there was anyone whose expectations Jesse knew not to play with, it was his own mother’s. At this thought, you are overtaken by a nervousness, an itch to become embroiled in the middle of something. You consider sending a text message to Alisa, but then you realize that you don’t have her number. This brings to mind the glaring fact that she reached out to Julien and Andrew (the original poster on Facebook, whose message Julien had shared), and not you, for a reason: they are, at this point in time, Jesse’s closest friends. And what are you? You tell Julien to keep you posted, that you want to be helpful in whatever way you can. He says that’s good, you’ll be needed, and hangs up.

That night, in your dreams, you reenact a moment from your childhood with all the awareness of posterity. You are maybe ten years old and it’s nighttime at summer camp. The cabin is thrumming with boyhood activity: candy bars being swapped for bowls of instant mac and cheese, Gameboys clicking in the distance, humming their 8-bit music. Amid all of this, Jesse sits on his top bunk, his black hair long and ratty and spilling over his brow, sulking.

You get up and approach him with candy and ask him what’s wrong. He takes one and tells you that he is angry with his dad. You know his parents are divorced, but you don’t prod. The two of you sit in silence and eat Sour Cherry Blasters, until he tells you that he’d like to sneak out of the bunk at night, steal one of the canoes on the camp beach, and paddle it as far as the lake goes. You can’t think of how to respond, so you just say: “Can I come with you?”

Early the next morning, you ask Julien for Alisa’s number. You text her, dallying around the caveats about the two of you not having spoken for a while, and offer your help, which she accepts.

I do not know if it helps to put “you” in my shoes, narratively speaking. It is not a question of whether you can imagine (what a stupid thing to say, I can’t even imagine). The day I described, October 14, 2017, was real. Jesse Galganov was real—you may even have heard of him. Our friendship was real. His face and hands were real. His dreams were real; he was going to become a doctor. He was only twenty-two years old when he went missing. We call out for him but receive only our own voices in return. The rest is silence. Can that also be real? What I am trying to do is make you understand, so that I can understand.

Jesse Galganov has not been heard from since September 28, 2017. He woke up that day in Huaráz, Peru, and made his way to the head of a hiking trail a few towns over. Then, he vanished. In the days, weeks, months and years that have followed, all of us, all of those who knew and loved Jesse, have asked: How? And: Why? We’re still waiting for answers.

What does it mean for a person to go missing? The first thing you experience is what I have come to call, in the privacy of my own mind, The Interval. I am talking about a breakage in time, a wheel that has come loose from the tracks. There you all are, gliding along the same timeline, the destination obscure but the way predictable. And then, without anyone taking notice, someone falls off. At that very moment, he slips onto another track, and time forks. Only you don’t know it yet.

The Interval is that moment between noting that someone is not where you expect them to be and deciding that this constitutes an emergency. The temptation in a case like this, paradoxical as this may be, is to wait as long as possible. In Canada, over seventy thousand people are reported missing by the police every year. The vast majority of them are found within hours or days—why should this case be any different? Maybe the forking path curves back around not far ahead.

What seems inexplicable now will surely be explained in due time, your worry turned to foolishness. Strangely, the only thing holding you back from sounding the alarm, from sundering the normalcy that otherwise dominates your life and declaring a state of exception, is the fear of shame. How stupid you’ll look, how embarrassing for you, how much scorn you’ll be in for, if you cry wolf when there is none. All that panic for nothing.

When it came to Jesse, what went unspoken in that long pause over the phone was the belief that he loved The Interval, that he had often romped and ruminated there, that The Interval was where he left and found his freedom whenever he needed it. Surely, if we waited just a bit longer, if we urged universal calm, he would be back.

I remember the first months of Jesse’s disappearance as being unmitigated chaos. Within two or three days of Andrew’s Facebook post, Alisa was in Peru, wrangling a few different kinds of police (local, Peruvian, North American). In an email chain I started with a New York Times reporter who was interested in the story, Alisa mentions already having been to the Canadian and American embassies in Lima (Jesse was a dual citizen) by October 19, five days after the post.

As I remember it, the rest of us, remote from the scene and in most cases from one another, flailed about for a foothold. But the evidence refuses this memory: every email, every record, is imbued with purpose, with direction—even as none of it would ultimately lead very far. Finding Jesse was a project, and each of the smaller tasks of which it seemed comprised cut a straight path through the noise of uncertainty. In the early days of October and November 2017, no lead was too improbable to pursue, no bush too small to whack.

A whole collection of Google Docs on which I am shared tells me just how many people were immersed in the effort: about thirty-five people who knew or had met Jesse were closely involved in tasks like “aggregating leads,” “monitoring main suspects,” and sifting through comments on the new Help Us Find Jesse Facebook page, all of which was work we had assigned to ourselves, not knowing how useful it might prove to the authorities. (They seemed hard at work in their own right, though their methods and objectives were opaque to me. I remember feeling like we had as much of a hope of tracking down Jesse as the police did.)

Twice that number were friends of friends who had heard the news and offered their invaluable help on at least one occasion. A college friend of mine from Ecuador, for example, offered critical support on dozens of English-Spanish translations; a high school friend was responsible for managing a GoFundMe page to support the search effort, which now involved a privately hired Israeli search and rescue company called MAGNUS; another friend helped me run the Facebook group; still others were tasked with reaching out to travellers on message boards about backpacking in Peru.

Many thousands of people not directly involved in the search effort brought Jesse’s disappearance to vast public attention by sharing news about him. On October 15, with the help of Google Translate, I made a poster announcing a reward for anyone with information leading to Jesse. Boosted Facebook posts featuring the reward poster reached, if I recall correctly, over fifteen million people in Peru, about half the country’s population. On October 22, 2017, Alisa informed those of us intimately involved that the biggest news magazine show in Peru had just run a major segment on Jesse’s disappearance.

The story’s growing international attention only confirmed the importance of our work and accelerated the mad thrum of our collective activity. That no detail could be too small drove many of us to the furthest reaches of our sanity. There were two months when I hardly slept—and I am certain that the situation was much worse for Alisa. The rest of my life was reduced to a simmer. I arrived to work late, eked out a minimum of productivity, and left early.

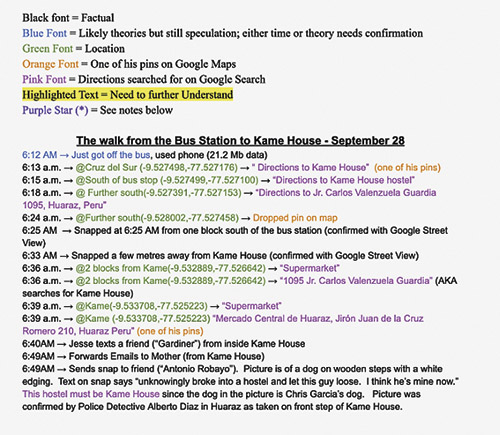

During the first few weeks, I stayed up most nights chatting online or on the phone with three of Jesse’s closest friends, Greg, Jonathan and Dylan, trying to trace his exact movements up until his disappearance. We had three resources at our disposal: access to his iCloud account, access to his Google accounts, and access to Snapchats he had sent to his contacts. The first of these allowed us to read through his Notes app and confirm that he had planned out, in detail, how much it would cost to take the various buses he needed to take from Lima to Huaráz, and from Huaráz to the trailhead a few kilometres away. One or two people who had met Jesse in Lima, and who had come across our far-reaching social media campaign about his disappearance, reached out to us and confirmed his travel and hiking plans—he had spoken excitedly about them.

The information from Google Maps gave us the strongest impression of a breakthrough. The application’s history told us not only what queries Jesse had searched in Maps, but also where he was when he searched them. The crucial thing we lacked were eye-witness accounts of Jesse after the morning of September 29, when he was supposed to depart for his hike. Even the two accounts we did have—that of the hostel manager who checked him in, and that of a street camera that picked him up in town—didn’t give us much in the way of useful information regarding his disappearance.

The Maps data gave us the next best thing: a satellite eye, watching in periodic blinks from above. Greg and Jonathan were able to put together a timeline of his movements through the first twenty-four hours after his arrival in Huaráz as a result. At times we became convinced that Jesse had never reached the trailhead, and that he was therefore somewhere nearby, in Huaráz or perhaps a neighbouring town. What I mean is that, some nights, we sensed we were hot on his heels, only a few paces behind him. The prospect of divining his whereabouts seemed possible.

Looking back, so many of the details gathered on the timeline struck us as essential. None of them turned out to be. It did not, in the end, matter which hostel he stayed at, nor when he checked in. It did not matter where he bought his lunch, nor his food for the hike. It did not matter when he boarded a bus, nor where that bus stopped on its way to the trailhead. It did not matter who he met along the way. The thing about building a timeline is that any theory of how best to fill in the blind spots can be annihilated by the most incidental point of data further down the line.

We were ready to believe that Jesse had never made it to the hike, that he had been swindled at the hostel, or robbed on the bus, or kidnapped by a cab driver one or two towns over. He had never paid the registration fee at the trailhead—so he must never have been there. But was that not so typical of Jesse? Had I not dreamed of him on some half-slept night ducking the rope that would otherwise keep him from his goal? It was; he did.

By late November 2017, Alisa informed us that a pair of hikers had run into Jesse on the trail, two days into his hike. He had been complaining of a headache. Nothing on that timeline means anything to me now. It is a fossil of our dispositions, a record of a long-lost innocence. If it accomplished anything, it was to keep us from the blackness that lingered at the edge of our thoughts. Each step we could track was the slenderest breath of life. But it did not help us find Jesse.

At a certain point imperceptible to me, I stopped believing we would. If he had suffered from altitude sickness on the trail, and had lost his way, fallen a long distance, or gotten stuck, how could he have survived more than a week or two? What was it exactly I was hoping we’d find: my friend turned master woodsman? (He was anything but.) Or some pathside kidnapper (who would have to be very strong, daring and sly indeed to disappear someone from a well-trafficked trail) who, following the news, would come out of hiding once the reward reached an adequate sum?

I felt increasingly very alone in the thought that I would have to begin mourning Jesse, far away not only from him, but from the community we shared back home in Montreal. How much was I missing back there? Who was gathering, commiserating in my absence? In the mornings I awoke beside my partner and took the subway to work. After work, I came back home, ate, and sat for hours at my computer, waiting. For what? Emails? No: just waiting, anxiously, like an engine stalled on a steep hill.

In many ways I am still waiting, and the record of those months—the timeline, the emails, the documents—bring me no clarity, say nothing to me. I am drawn instead, as I look back through my emails, to the photographs he took the day before his hike, walking through Huaráz as the sun rose and burned off the morning frost and swung its way across the sky. He had saved the pictures to his Snapchat. They are perfect because they mean nothing, are evidence of nothing. A simple human reflex in the face of minor astonishment.

Sometime late in high school, in the winter of 2010, I found myself parting crowds at a house party looking for Jesse. We had not arrived together, but I wanted to confirm that we would indeed leave together. I was to see a friend the following day in Côte Saint-Luc, the Montreal neighbourhood where Jesse lived with Alisa and his sister, Sammi. He had said I could stay over.

I found him in the kitchen talking to some of his school friends, a bottle of beer in hand, his flannel shirt open over a navy blue t-shirt. He saw me and laughed; we were wearing practically the same thing. I confirmed our plans, pulled a beer from the fridge, and joined in the chatter for a while before drifting elsewhere, looking for other friends, maybe someone I could flirt with. I was overtaken by euphoria; everyone looked great, everyone was smiling, the light was dim and close. The heat of so many bodies was intoxicating.

A couple of hours later, I bumped into an old friend I had known since the early summer camp days, who matter-of-factly said, “Galgy threw a fit and left.” Galgy was one of many unimaginative names we had for Jesse. “Left? Like, left left?” He nodded. I asked why, he shrugged. Another friend, who had been eavesdropping on our conversation, said that Jesse had gotten into a fight with his girlfriend and stormed out. I took out my phone and called him. No answer. A group of guys I vaguely knew were smoking weed on the front lawn, shivering in the freezing air. I asked them if they had seen Jesse, and one of them pointed down the road. Beneath the arcing series of streetlamps a smudgy form could just be made out, receding from view.

I sprinted towards him. Jesse had his jacket under his arm. He was steaming, literally, the evening air inhaling the waning warmth of his body. Out in The Interval. He looked back at me as I approached, but didn’t say a word. We walked together, and I asked him a few questions. Why didn’t he tell me he was going? Should we take the bus? Or did we have enough money between the two of us to call a cab? Wasn’t it too cold to go on foot? But he was gone somewhere in the distant orbits of his mind, not really hearing me. “Jesse,” I said. “We’re an hour’s walk from your house at least.”

Eventually, I shut up. We walked through Westmount and onto Côte Saint-Luc Road, which was icy. Carefully, we picked our way down. Every now and then a car passed, music seeping through the window panes, and I wondered if the people in it were coming from the party. After an hour and a half we reached his house. We had a snack, drank some water. I laid out in his basement on the green leather couch I’d slept on many times before. He said not a word.

For four years I dreamt recurrently about Jesse. I’m on a train, in an empty car. It’s raining outside and the roof is leaking; first only a little, and then in torrents. Water pools at my feet, my body shuddering in the cold. Without knowing why, I push ahead to the back of the car. At the very back, sitting in the last seat by the window, is Jesse, looking out at the passing mountain landscape. He is drenched, and his hair seems to be draining black ink onto his shirt. I ask him where he is. He turns to me, looks me in the eye. But he doesn’t say anything. He just puts his index finger to his lips, and I know to be quiet. I would wake up feeling that he was asking me to give him time, that he’d be back soon. I just needed to hold his space for him.

An unsolved disappearance hangs over you in ways typical grief does not. Unlike death, it is not an end to something. It is an open parenthetical. What if he comes back? What if one day he shows up at your door, tears in his eyes, only to find out that you’re not home because you’re presiding over his funeral? You feel yourself condemned for any behaviour normally demanded of mourning’s progress, for any attempt to grieve and move on.

What if?

Sometime in December 2018, more than a year after Jesse’s disappearance, Julien and I went to see Alisa at her home. She had texted us a few days prior, and we arranged to stop by and catch up, the two of us anxious to see how she and Jesse’s sister, Sammi, were doing. We hadn’t discussed what we’d say to her, though he and I knew each other’s feelings: that, by one means or another, a new page had to be turned. If we couldn’t find Jesse, it was time to remember him.

Throughout most of high school Julien and I were never much in the way of friends. In our last year, at a new school, we grew closer—because of Jesse. Through Jesse, I had met and befriended many people with whom I had only had a passing acquaintance. He was capable of that for as long as I knew him. Once, in the middle of college, on a hiking trip in New Hampshire with Julien, Jesse and Andrew, I reflected that we wouldn’t be there together if it weren’t for the magnetic attraction that he exerted on all of us. We had all become renetworked through his hub.

When Jesse disappeared, the kinship I felt for Julien deepened. I can’t explain it except to say that we were in the trenches together. In many ways, being perhaps closer to Jesse in recent years than any of us, he was the one we all looked to for direction (or hope), other than Alisa herself. In the early hours of uncountable mornings, Julien was the one to whom I could vent, and who would offer in turn fresh ideas for the search, unconsidered possibilities, and general encouragement.

We greeted each other outside in the snow and composed ourselves before ringing the bell. Inside, the house that I had known well as a child seemed the same as it had always been. There was the kitchen counter where I had watched Jesse, at fourteen years old, eat an entire jar of banana peppers. There was the patio door and the small rug laid out in front of it, the same rug we had once accidentally lit on fire. The four of us—Julien, Alisa, Sammi and myself—gathered in the sitting room, where Jesse and I used to watch hockey games. We sat, we hemmed and hawed, we talked about (what else?) Jesse.

At one point, as if on unspoken cue, Julien and I told Alisa that we believed she should hold a funeral. Or if not a funeral, a memorial. The community needed the opportunity to grieve, we said, to mark the occasion. That was what people did, wasn’t it? Mark time, stamp it invisibly so as to dam its interminable flow, if only delusionally, if only for a moment. The punctum could not be postponed.

Alisa was still. She looked to the ground, searching for words. I regretted what we’d said instantly. At that moment, from the expression on her face, I understood just how wide the gulf between our respective attitudes toward the situation was.

I don’t know when it happened, exactly. But over the course of that first year I had convinced myself that Jesse was dead, that he would never be found, and that what was needed was a coffin without a body. For Alisa, this was out of the question. An entire search team was still present in the region. Investigations were still proceeding. Did he die of altitude sickness? It was possible. But then, where was his body? Where were his bright-coloured clothes and belongings? How does a person simply disappear without a sign? She would answer these questions. She would bring him home at all costs (and the search had thus far come at a significant cost, emotionally and financially, which she bore with a stoicism I could not fathom). Only then did I understand that bringing him home did not necessarily mean bringing him home alive.

I regret our suggestion to this day. Julien and I were wrong. There were good reasons to keep looking, even beyond the need to bring home the bones of one’s child. At that time, “foul play” was a term we batted around a lot, a simple euphemism for a host of horrors too chilling to mention by name. If there was foul play—if someone had killed him, or had found and buried him, and stole his belongings—would it not be justice to uncover it? To root it out and punish it? It would. The teams on the ground were still working. They were interviewing local muleteers who drove through the park where Jesse disappeared. They were searching glaciers and rivers with dogs. Every now and then, a trace or clue turned up. They do still—as when, this past January, unidentified human remains were found in the Santa Cruz area. Jesse’s homecoming may yet be on the horizon, obscure as it is to the mind’s eye.

The moment passed. I felt that we had hurt Alisa deeply, but we went on as before, a courtesy of her fundamental kindness, smiling over memories which we turned in our hands like old coins. Before we left, I told her and Julien about my recurring dream. And I told them about a moment in the Hebrew Bible that I couldn’t get out of my mind. (This was all the more strange for the fact that I was not and am not in any sense religious.) It is the moment just after Adam and Eve have eaten of the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge. They hear God enter the Garden, and they hide. God, present among them, asks: Ayeka? “Where are you?” Why would he ask a question for which he knows the answer? It had to be that he did not care that they hid from him. He cared only that, called upon to reveal themselves, they would.

We sat there and thought about it. Then Julien and I rose to leave. A few weeks later, the three of us went to a tattoo parlor in Montreal and had the word ayeka marked indelibly on our arms.

It has been almost five years since Jesse’s disappearance and I don’t know what it means for me to write these words. I have tried to write about this period of my life many times since it began. The first attempt was a poem, written four weeks after I first saw Julien’s post online. (I won’t subject you to it.) There is, even now, something disingenuous about me telling this story. It isn’t my story. It doesn’t belong to any of us, except perhaps Alisa, who raised Jesse and fed and clothed him, and cradled him and taught him and laughed with him and saw him through his darkest days, and Sammi, whom he loved more than anyone. Recently, I’ve had nightmares about writing this article—about finding him on the steps to my apartment with a look of grave disappointment on his face. Didn’t you know it was a joke?

I know less and less about how Alisa and Sammi are doing. With time, as the search became the exclusive object of a far greater expertise, I learned to disengage, to drift back into my own world, into my work and life. Every now and then we talk. I tell Alisa when I’m thinking of Jesse, especially on February 8, his birthday. Julien and I walked with Sammi in the Old Port over a year ago; it was sweet. I know Alisa’s still looking, still hoping, still moving courageously through a life wracked by unthinkable pain. I can’t think of what to say to her that isn’t already a trope. All the language I have is like dead coral upon the reef.

In the last years of our friendship, Jesse and I weren’t as close as we had once been. We spoke infrequently, stopped exchanging confidences. We had spent college apart, had fallen out of and into love, had met new people. But whenever we’d meet, whenever he came down to New York to visit me or we exchanged rounds of drinks in the back of a dark tavern in Montreal, something old and unsayable between us reasserted itself, and I felt that the younger versions of ourselves were reaching out to one another from deep within the people we had become. The people we were becoming. He was going to be a doctor. He was going to travel the world. He was going to send me a poem he had written (he wanted me to see it). None of this happened. None of it will.

There’s nothing really to be made of the fact that the last thing I said to Jesse, after hugging him goodbye and wishing him good luck on the curb outside of Bishop & Bagg pub, was, “Don’t die.” He had spent the evening with glowing eyes telling me how excited he was for his year of self-discovery. He said those words, self-discovery. He needed that. He was taking the time for it, which I admired and envied in equal measure. He asked me for book recommendations for his Kindle. He told me how he got his packing down to a science, that his backpack for the entire trip didn’t exceed some minuscule weight (24 pounds, I think).

“Don’t die,” I said, smiling. It was a joke—an interpersonal one to match, unwittingly, the cosmic one that was about to be played on all of us. It is the kind of thing you say when you believe in your bones that there are still years ahead of you, that the fruit is ripe to be squeezed now, that one day you’ll be old and soft and nostalgic, staring with watery eyes into the twilight, and you’ll be better able to say to one who has given you the gift of friendship what you really mean: I love you, I miss you, don’t you die. ⁂

Ben Libman lives in Montreal. He has written for the New York Times, New Left Review, the Yale Review and other publications.