Illustrations by Constante Lim/Unsplash; Michael/Unsplash

Illustrations by Constante Lim/Unsplash; Michael/Unsplash

Carousel

Translated by Katia Grubisic

The years fly as the slides shuffle by. The wheel spins, dangerously excited. The child in me wishes she could step off the carousel of time, though she claps as the slightly sordid, merry mechanism laps the years one over the other, slippery and sliding into each other endlessly. There is something disturbing about the noise of the projector that automatically rotates through each stilled instant of life. Click, clack. The past appears, click, clack, disappears, click, clack, appears, disappears, strange discontinuity.

Click clack, click clack, I try not to get dizzy. The clatter of photos in the machine blurs into the crash of falls and car accidents along the highways of memory. Yet as the images come to life on the makeshift screen of my dull apartment wall, time stands still. The slides are silent; only their hectic succession whines along. On the carousel, photos repeat like an echo. The projector machine-guns me with the past, blinding me with lights and colours that hurt even though they’ve grown dim. Every burst whispers some torment.

On the cardboard boxes of what my mother used to call, with a slight affectation, the Kodaks, existence is marked by its own punctuation. My mother’s jottings are magic words that were supposed to provide access to our past one day, if we so desired.

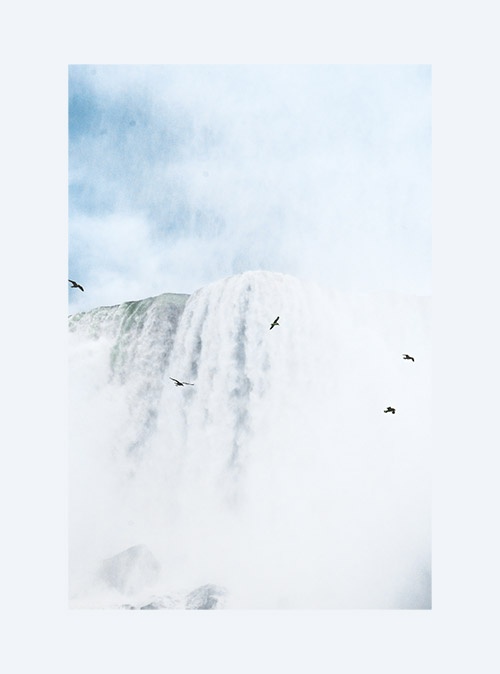

1964, Niagara, Chicago, Gary at Christmas.

1965, New York, Washington, Niagara.

New Year’s Day, Montreal.

1966, Gary, Niagara.

1967, Toronto, Gary, Bay City, Niagara Falls.

Expo, Montreal.

1968, Memphis, Chicago, Niagara (on the way back). Toronto.

1969, Niagara.

1971, Paris, Florence, Nevers, Niagara, Bay City.

Gary.

1972, Rawdon, Niagara.

1973, Niagara, New York, Boston, Cape Ann.

1974, New York, Niagara, Gary.

1975, Niagara (June and December).

1976, Niagara, Gary.

Bay City.

1977, Chicago, Gary, Niagara.

1978, Niagara, Gary.

Each year, there I am again, next to my mother. We never miss our date with the camera, at the railing in front of the falls. She and I play at mimicking each other, half aware that we’re doing it. We recreate the same pose from 1964. She trades in her seal-skin boots for green pumps or red flats, depending on the season and the fashion. In one snapshot she’s Clairol Auburn, later on L’Oréal Champagne. For a brief click, she shows up in a red wig she’d bought on Jean-Talon and which I kept, then dissolves and pops up again in 1967 with curly extensions pulled into a ponytail, and then with a yellow silk kerchief tied over her hair. In every picture I look like a doofus, even in that white dress my mother brought back from Portugal, in a denim getup like some American, or when I had bangs like Audrey Hepburn in Breakfast at Tiffany’s. Time goes by and I turn into the person I’m going to become. It’s clear that I’m coming to terms with my mother falling away beneath the surface, disappearing into the falls. I am getting used to her possible absence.

When I was young, we would stop in Niagara every year on the way to Gary, Indiana, or Bay City, Michigan, where my mother’s two sisters lived. It was a family honeymoon. I can see it on the Kodak boxes. We were rebuilding the family piece by piece for a dip in the falls, diving headfirst into our habits, our rituals, our beginnings. Before the waterfall. We were appraising our stubborn attachment to living. Look … There we are, there’s us again in Niagara! The years go by but we stay the same.

1965. Interesting: I no longer look panic-stricken like I did the year before. From 1968 onward, I feel like I’ll be able to survive my mother’s plunge into the waters of death, when it comes, sooner or later. No one can escape the weight of their own body as it goes over the falls. We all end up dragged into their swirl; habit takes care of the rest.

Nearly three million litres of water flow over Niagara Falls every second. Every time I go I’m astounded by how blatant that power is. If Maman fell in, she would never make it out. All that water, so much water … drowning is inevitable, if not today then tomorrow. As a child, I have to get used to the fact that my mother will die. And I do. The slides are evidence of how docile I am. That’s life: death catches up with us somewhere along the way and shoves us over the Bridal Veil Falls or the Horseshoe Falls when we least expect it. All it takes is a strong wind and in five seconds we are swept away.

I’ve heard that almost 90 percent of the fish that swim down the falls survive thanks to the pillowy foam that catches them as they slide into the water. It’s different for humans … though of course my mother survived her own death. Like a fish, she launched off, stronger than before, and on she went. But that doesn’t mean she didn’t fall. How harsh, how ruthless. I can’t see her anymore, and I fight to find her again in my riparian delusions.

The photographs show my family’s relentlessness in making the same journey, in finding ourselves as we are, but they also reveal our surrender to the passage of time. Even Benjamin Button, that famous character of Fitzgerald’s who starts life at seventy and ends up as an infant, follows an inexorable chronological sequence. Even though he pushes against the normal course, as a salmon might swim up a waterfall, he can only go in the direction imposed by the flow of life—against the current. In the world of the living, there is little room to drift. Only along the Mississippi, posthumously or in literature, can we stray from the course laid out for us. We can be unhinged, give in, maunder downstream, along opposing currents and with words in books that let themselves go under. We learn freedom.

1969. The 1969 Niagara photos are wrong, confusing. For a few minutes, I slow the scuttle of the images. In the background, far behind my mother and me posing for my father’s camera, is a huge pile of rocks. Instead of the water flowing in the distance, which we pause every year for an instant, there is only a large pile of rocks. The falls have been erased. In 1969, the water is missing. Where have the falls gone?

I can’t believe my eyes, but more than anything I’m especially surprised that I have no memory of that moment, of the year Niagara Falls disappeared. I stood there, in front of the absent falls, not paying attention. Did the film rub out all the water and turn it to stone? It seems impossible, and I set out to find out what happened. Apparently, as I learn, in June 1969, engineers diverted the flow on the American side for several months to assess erosion. A six-hundred-foot dam redirected the Niagara River to the Horseshoe Falls on the Canadian side or upstream of the Robert Moses Powerhouse. That’s why my falls were gone.

1972. More pictures of us up top and then a few more on the Maid of the Mist in the whirlpool behind the big falls. I look completely dishevelled. My mother has folded a large scarf over her head, and her hair will hold up, keeping up appearances. It’s obvious she doesn’t have any kind of sea legs, and nor do I, for that matter. The slides show us nauseated and livid: please, let this ridiculous river jaunt end soon. Deep water is definitely not our thing. That’s what we tell ourselves, naively, in that moment. It’s a blessing we have no idea what’s to come. We expect the Maid of the Mist to return safely to port, an unpleasant experience soon forgotten. Il était un petit navire qui n’avait ja- ja- jamais navigué, the song goes, though this ship has clearly had its fill. In any case, we won’t be sailing back under the falls again, at least not in this lifetime.

1977. I’m still with my mother in front of the railing, with Amandine and Clémentine this time too. They’re striking a pose for the camera, putting it on, for posterity. They fake me out, pretend to jump, trying to scare me, but I’m fourteen years old and beginning not to be frightened at all by the power of the falls. I’m wrong. My cousins are thinking that one day we’ll look back at those snapshots of our wild youth.

Those are the last pictures we ever took of the twins. Two little girls on the edge of the abyss, dead girls in the making ... completely unaware.

1962, ’63, ’64, ’65, ’66, ’67, ’68, ’69, ’70, ’71, ’72, ’73, ’74, ’75, ’76, ’77, ’78, ’79. All the years in a row and then the slides stop suddenly and without warning. The emptiness is a sign of the times, of moving on to other ways of recording the slack hours. Existence sounds different after 1979, in our country, its noise the crackle of glossy paper we mar with dirty fingers. The end of an era and my cousins were run over by a big blue truck. In our house, after 1979, we get photos developed and we pile them up on our desks and all over the place, we shuffle them around like a deck of cards, like we are trying to see into the future. We handle them roughly. There are always two copies, one to give to friends and one to keep in your purse. You pay a dollar more and you get a copy of everything. This is how we preserve life now, what remains of it.

2022. Why should the falls drag me down here at five o’clock in the morning? To show me how big they are and how small I am? So begins, almost, Henry Hathaway’s breathtaking Niagara. I repeat the words to myself today as crashing water beckons from my dreams: through these photographs of the past, come back.

In the film, George Loomis, played by Joseph Cotten, walks by the falls at dawn. He can’t turn away. The falls … They foreshadow his anger, his anguish. From the start of the thriller, we understand that this wounded man will be like Niagara Falls. They swallow humans and boats, they consume any craft, any body that ventures in. There is something monstrous about them in which Loomis sees himself.

Yet they are even more powerful than he is, and they will eat him up. He ends up killing his wife Rose, who is played by Marilyn Monroe, and then perishes himself, falling into the gorge carved out by the water.

2022. I loop through the slides for hours, watching my mother fall and fall a thousand times, though at the railing and in all the photos she stands firmly on her two feet.

I am dead, she shouts to me from the depths of time. Nothing else can happen to me. I’m dead, so never mind if I fall. You should be relieved. There’s nothing for you to be afraid of anymore. But my fear has come back. I’m the child from 1964 whose mother was stolen away by Niagara.

Books tell us the Mississippi River is seventy million years old. What a long time to be on earth. Will I make it down to the Gulf of Mexico in time to catch my mother? Or will she manage to run away from me again and again? Shouldn’t I just jump into the falls now and see where the water takes me? There would be a big splash, and then, quickly overcome by dizziness, I would magically find myself passing through the Illinois waterways, canals and locks, along the Mississippi. I would be mistaken for a tree uprooted by the water and dragged into the river, or else the corpse of someone gone missing, poor wandering soul.

Geologists predict that fifty thousand years from now, the falls will be gone. At the rate erosion is going, they won’t last long. And my mother, who has spent her life and her death throwing herself in, will have to give up her little routine.

A day will come when she won’t be able to spend every moment dying in Niagara Falls.

The origin of the word niagara, in one of the languages of the Americas, refers to a passage—through land, through time. Both the word and what it implies will fade away, they will have no meaning any longer.

Maman won’t die, and Niagara, yes, Niagara will be gone. ⁂

Translated from Niagara (2022), published by Éditions Héliotrope. Reprinted with permission from the publisher.

Catherine Mavrikakis has published a number of novels, including Le ciel de Bay City and L’Annexe; non-fiction, including Diamanda Galás; and an oratorio, Omaha Beach. Her work has been translated into several languages and has won awards such as the Prix littéraire des collégiens, the Prix des libraires du Quebec, and the Grand Prix du livre de Montréal.