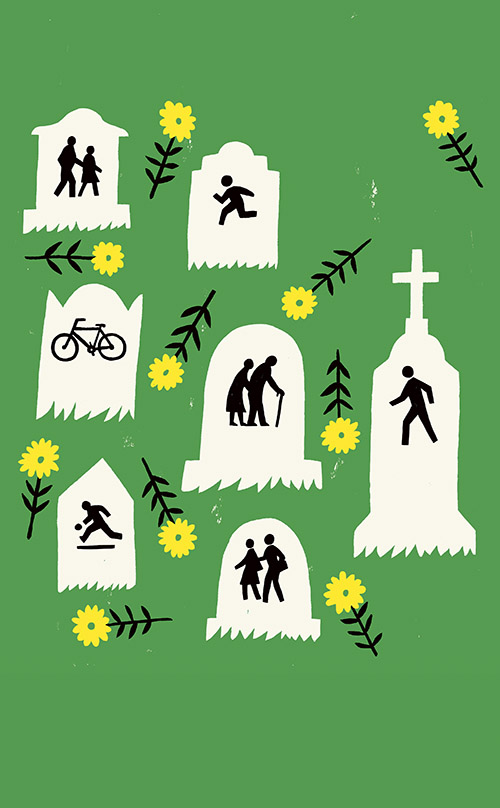

Illustration by Gillian Wilson

Illustration by Gillian Wilson

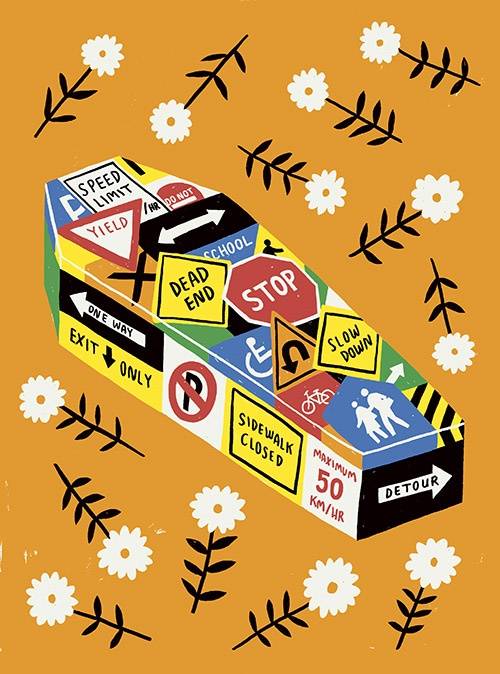

Right Of Way

Urban planners have long known how to keep pedestrians safe on our streets, Lana Hall reports. Canadian cities are letting them die anyway.

On the evening of January 7, 2018, Jessica Renee Salickram stepped off a bus onto Steeles Avenue in Markham, Ontario. The stop was 300 metres from the closest signalized intersection on a stretch of Steeles that doesn’t have a sidewalk. At nearly 10 PM, with snow piling up on either side of the roadway, the few streetlights didn’t do much to help with visibility. Salickram, who was on her way back from a shift selling shoes at the Eaton Centre, decided to cross the street mid-block rather than brave the cold and walk on the unprotected shoulder of the road.

Salickram was a ten-minute walk away from the house she shared with her mother, but she wouldn’t make it there. The driver of a minivan struck her moments before she finished crossing the street. She was pronounced dead in the hospital shortly afterwards, as police and family members scrambled to contact her mother and relay the unthinkable: her only child was never coming home. As the night wore on and crews were called in to reconstruct the crash scene, a lone blue-and-black sneaker lay in the middle of the road.

Salickram was just twenty-one years old when she died. She had graduated high school with honours, completed a journalism co-op placement at the Markham Economist & Sun and finished a year at York University before taking a hiatus from school. Her mother, Jacquelyn Persaud, who mostly raised Salickram by herself, describes her child as a wonderful soul, kind-hearted and ambitious. She mourns not only her daughter’s life, but also the life she’ll never live. “I’m angry,” she says. “I lost a future, you know? She would have graduated last year. I won’t get to see her get married, have babies, anything like that. I didn’t get to see her fall in love. It’s a terrible life to be living.”

Persaud says the driver who hit Salickram claimed that he didn’t see her on the road—there were no charges laid related to the accident, and neither the city nor the Toronto Transit Commission (TTC) took responsibility for the conditions that may have contributed to it. Persaud has since moved to another area and launched a civil suit against various parties that she believes should be held accountable for her daughter’s death. (Persaud’s lawyer has advised her not to name the respondents.)

Persaud’s pain is made worse by how easily these circumstances could have been avoided. Just ten months before Salickram’s death, a Markham resident wrote an email to the city’s mayor expressing concern about the site of the accident. They flagged that the bus stop had no light or crosswalk and that vehicles regularly crossed into the median, where they couldn’t see passengers getting off the bus. “Is the city of Markham waiting for someone to get hit or killed?” they asked.

The email was passed around to several municipal departments within Toronto and Markham, but no concrete action was taken to make the intersection safer prior to Salickram’s death. An email response from 311 Toronto indicated that the resident had to be more specific about the measures that they were requesting before the city would look into it. Installing streetlights at the intersection would require Toronto Hydro’s cooperation, while adding traffic signals to the intersection would require the TTC to be involved, for example. Another email noted that the area had been “flagged for infrastructure enhancements in 2020” and that a bus shelter couldn’t be installed at the time “due to the existing conditions.”

The TTC stop where Salickram was hit has since been taken out of service. In July 2022, a signalized intersection opened on Steeles Avenue and Morningside Avenue, about seventy metres away from the collision location. “Hopefully, stoplights in the area will alleviate some of the issue, but I don’t know for how long,” says Persaud. She feels the response to her daughter’s death has been inadequate. “The city needs to do something to make it more accessible for pedestrians, and not allow drivers off the hook,” she says. “If you get behind the wheel of a car, you’ve got a weapon in your hands.”

At the end of the nineteenth century, streets in cities across the Western world were filled with pedestrians, cyclists, streetcars, and the odd horse-drawn carriage. Pedestrian crossings didn’t exist before the First World War because there simply wasn’t a need for them. “Street space was just people walking around,” says Andre Sorensen, a professor of urban geography at the University of Toronto.

That changed in the early 1900s when the Ford Model T became available, since its affordability made car ownership accessible to the middle class. The number of registered cars in Canada jumped from 2,131 in 1907 to over fifty thousand by the start of the First World War, according to the Canadian Encyclopedia. In the coming decades, families continued to embrace the car’s convenience, which meant that traffic fatalities began to increase in kind, reaching 31,204 in the United States in 1930, according to the National Center for Health Statistics. In the US, this shift coincided with the rise of urban and regional planning centred around cars, a movement that developed in part to address the increase in pedestrian collisions. This trend would be copied in Canada, particularly growing around the 1950s, when the country experienced an auto boom after the Second World War.

At the time, urban planning had two goals: moving cars around as efficiently as possible and separating pedestrians and vehicles completely, says Sorensen. Beginning in the late 1940s, municipalities in Ontario began to insist on a suburban design for their subdivisions that consisted of arterial roads—without stores or houses fronting onto them, to reduce congestion—and neighbourhood units. But this design, central to so many Canadian cities, was always built on what Sorensen calls “a simplification of reality.” It was based on the assumption that men drove to work and back, while women stayed home with the children—and off the main streets. Planners gave little consideration to different family dynamics or how to safely integrate pedestrians and vehicles that might be travelling to the same destinations.

Canada’s population in 1950 was 13,712,000. Today, it’s 38,929,902. That growth has led to both more vehicle congestion and more pedestrian traffic, a combination that simply doesn’t work with 1950s road design. One example of design that lends itself to a chaotic pedestrian and driver mix, says Sorensen, is the number of bus routes that travel along major thoroughfares. For example, Finch Avenue, a major arterial road in northern Toronto, shuttled more than forty thousand people per day along the 36 bus route in 2011, according to the Toronto Star. Sorensen points out that nearly every bus trip is going to require people to cross the street at some point. “You’ve got tens of thousands of people who are pedestrians on streets that were designed assuming that nobody would ever walk on them,” he says.

In some cities, insufficient pedestrian infrastructure has inspired the use of a popular hashtag among planners, pedestrians and road safety advocates in North America: #DeadlyByDesign. People will tweet images of dystopian-looking intersections, decidedly not-pedestrian-friendly, and messages like, “It’s not an accident when that intersection is the location of countless crashes.”

Salickram was a casualty of this kind of oversight. In 2018—the year she died—the Toronto Police Service reported that forty pedestrians had been killed by a driver in the city. She was one of 323 pedestrians who died in road fatalities across Canada that year, according to the International Traffic Safety Data and Analysis Group (IRTAD). That year, the group issued a report that revealed Canada was among only seven of thirty industrialized nations studied where pedestrian deaths were on the rise. Over the same period, deaths of other types of road users in Canada, such as cyclists or car occupants, had decreased. So far in 2022, Toronto has seen twenty-one pedestrian fatalities. In 2021, Halifax had three pedestrian-involved fatal collisions and Vancouver suffered eighteen traffic-related fatalities.

These figures persist despite the fact that many Canadian cities have adopted an approach called Vision Zero, which has proven successful in transforming the relationship between drivers and pedestrians in cities across the world. The traffic safety initiative originally launched in Sweden in the late 1990s with the aim of eliminating traffic fatalities and serious injuries in the country. While it has yet to reach its goal, Sweden’s actions resulted in dramatically fewer pedestrian deaths and injuries: pedestrian deaths across the country fell by 65.8 percent from 2000 to 2020, according to IRTAD.

The framework encourages city planners and policymakers to prioritize safety in new developments, analyze current design for safety improvements, and focus on designing transport systems where accidents won’t result in serious injuries or death. It doesn’t look the same in every region—municipalities are left to design their own processes around a shared end goal. But in Sweden, measures have included installing central barriers to prevent head-on accidents, speed enforcement cameras, and replacing four-road junctions with roundabouts. The country has also tried to centre vulnerable road users such as pedestrians when designing urban traffic environments.

A few other European countries followed suit, with similarly positive results. Norway adopted the framework in 2002, having already seen an overall decline in traffic fatalities since the 1970s. The country invested heavily in public transit and in infrastructure for pedestrians and cyclists. In 2015, its capital city Oslo changed its approach to traffic fatalities and committed to prioritizing pedestrian and cyclist safety. The city introduced a series of changes, including setting a goal to reduce car traffic by one third by 2030. After having witnessed a rise in serious traffic-related injuries from 2012 to 2015, those kinds of injuries were reduced for the next four years.

Oslo transferred the power to designate bus lanes, bike lanes, and one-way and closed streets from police to the municipal government, allowing for the speedy creation of new bike lanes and closure of through streets. A cycling strategy aimed to increase bicycle mode share—the percentage of people using bicycles versus other modes of transport—to 25 percent by 2025. Perhaps the most widely reported change was the city’s promise to significantly reduce cars in Oslo’s city centre by 2019, doing away with through traffic and regular street parking. In 2019, no one died while walking or cycling on Oslo’s roads. Political consensus among decision makers resulted in a remarkable change to the city’s relationship to pedestrians—and Oslo took steps towards environmental goals in the process.

Since 2015, eighteen Canadian cities have adopted Vision Zero, including Toronto, Edmonton, Montreal and Halifax, according to Parachute, a national injury prevention charity. In Edmonton, traffic-related fatalities dropped by 50 percent between 2015—when the commitment to Vision Zero was made—and 2021. Pedestrian fatalities and serious injuries fell by 27 percent over the same period. The city’s default speed limit is now forty kilometres per hour. But the path to success isn’t clear: the overall Vision Zero framework doesn’t come with any specific steps or directives.

As such, Canadian cities have admitted to varying rates of success with Vision Zero. While Toronto adopted it in 2017, forty-one traffic fatalities occurred in 2020. “This is something that we’re in the long game for,” the city’s director of transportation project design and management told the Toronto Star. A presentation on Halifax’s Strategic Road Safety Plan stated that “zero deaths and injuries cannot be accomplished in the immediate future.” And a spokesperson for the Halifax Regional Municipality wrote in an email that zero deaths and injuries “is a long-term vision, not a short-term goal.”

There are some commonalities between regional strategies: the cameras, the roundabouts, pedestrian crossovers. But since it’s largely left up to each city to find funding and achieve Vision Zero’s goals as it sees fit, results vary widely. The cost and scope of implementing Vision Zero deters many cities from adopting the approach, says Sorensen. Across the country, road safety advocates say the stakes are too high for pedestrian mortality rates to be decreasing so gradually.

For families left behind, redesigning cities for reduced traffic death is only one part of the problem. Those who have lost loved ones want drivers to be held accountable when they’re at fault. “A driver gets a fine and gets to walk away?” asks Persaud. “That’s not right—we live with the consequences forever.”

Jess Spieker was riding her bike northbound on Bathurst Street, near Toronto’s affluent Forest Hill neighbourhood, when her life changed permanently. A driver in an SUV hit her, smashing her spine, and causing a brain injury and a blood clot that later travelled to an artery in her lungs, nearly killing her. “She made [the turn] at a pretty good clip,” says Spieker, “and I slid up the hood, smashed into the windshield and was thrown pretty far and landed on the pavement.”

According to Spieker, the driver pled guilty to improper use of their turn signal, a charge under the provincial Highway Traffic Act, and received no demerit points on their driving record. She says the driver paid a $300 fine, and that was it. Spieker now deals with persistent anxiety and depression. But she’s also channeled her energy into working for change: she’s a spokesperson with Toronto-based Friends and Families for Safe Streets, a group that works in road safety advocacy and runs support group meetings for those impacted by road violence.

Theoretically, a lot of work in this vein was supposed to have been done between 2017 and 2021, when Toronto’s Vision Zero Road Safety Plan was meant to have wrapped up. The city’s plan aimed to lower fatal or serious injury collisions by 20 percent by 2026. It included over fifty new safety measures. In 2018, for instance, fifty-six leading pedestrian intervals were installed, giving walkers a head start before vehicles can proceed. So far, though, it seems like the city hasn’t actually become safer to traverse by bike or on foot—at the time of publication, Toronto has seen twenty-two pedestrian and cyclist traffic-related fatalities this year. “The stats in some ways speak for themselves,” Matti Siemiatycki, a professor of geography and planning at the University of Toronto, told the Toronto Star.

Spieker, too, says the city’s efforts are falling short. She says urban centres need more comprehensive infrastructure to protect pedestrians, such as raised crosswalks and tighter turning radii at intersections, both of which have been proven to combat excessive speed. Something close to a ninety-degree turn, for example, would require drivers to turn more slowly than a gentler curve, says Spieker, which can be taken at higher speeds, possibly to the detriment of a pedestrian who may be crossing. “That’s a very simple and cheap design change to make that we just don’t do here.”

These problems exist nationwide. Sandy James, a city planner and the founder of Walk Metro Vancouver, a nonprofit promoting walkability, says the issue extends to the way that roads and cities are conceptualized and designed to begin with. Our culture currently treats pedestrian fatalities as an inevitable collateral of people using cars, says James. “We have to change that parameter.”

Intersection design is one problem area. Due to the large number of vehicles and pedestrians at intersections, they’re a high-risk area for collisions. Reports show that collisions often occur when drivers are turning while pedestrians cross with the right of way. James knows pitting car users against pedestrians doesn’t take into account the complexities of road-use politics. Instead, the way road safety changes pan out will depend on the city in question and its specific design or design needs. In Vancouver, for example, speed is a major factor in pedestrian deaths. “We know that if we implement thirty kilometre-per-hour zones, city-wide, that we will automatically lower incidents by one third,” she says.

James is aware that other cities have experimented with this kind of policy under their Vision Zero initiatives, like Edinburgh, UK. Research in Edinburgh suggested that for every one mile per hour that average speeds are reduced, the collision rate should fall by about 5 percent. Collisions were reduced by almost 30 percent within the first three years of implementing a twenty-miles-per-hour speed limit, compared to the three years before the rollout. The city estimated that costs saved by the reduction in collisions since the new speed limits took effect amounted to more than $60 million dollars.

The Union of British Columbia Municipalities has asked the province to give them the authority to implement more thirty-kilometres-per-hour zones, James says, but has been denied. These types of zones require frequent signage throughout, which is cost prohibitive for most municipalities, she says. Surely, though, it’s worth the expense.

Some Canadian cities have proven that a combination of policy, investment, and design can work. In 2019, the City of Surrey, just southeast of Vancouver, set the goal of reducing the rate of collisions resulting in death or serious injuries per one hundred thousand people by at least 15 percent over five years. A report presented to city council in November 2021 revealed that crashes resulting in serious death or injury had actually dropped by 22 percent. In a single year, the city installed fifteen speed bumps, thirteen full traffic signals, eighteen left turn signals, twenty-four flashing lights at crosswalks and twenty-three kilometres of sidewalks. Police issued 2,050 distracted driving violations and 1,546 immediate roadside prohibitions.

When Surrey started its Vision Zero program, the approach went beyond road improvements, says Rafael Villarreal, the city’s manager of transportation. “We took a more holistic approach, a public health approach.” That involved using data to determine where the most serious crashes were likely to happen: at intersections, and in specific neighbourhoods. This led to actionable plans, he says, including the implementation of fully protected left turn signals. “In Canada we have unprotected left turns, and that creates some of the most severe crashes because you get a direct impact from the vehicles. So the more that we have protected left turns, the more we can prevent those severe collisions.” They mapped the whole city to identify where most of those were happening, and prioritized changes accordingly. Leading pedestrian intervals have helped, too.

The key takeaway, Villarreal says, is that these changes take time. The city is now getting recognized for work it started ten years before it implemented Vision Zero, with measures such as the first installations of leading pedestrian intervals. “There is no overnight success,” he says. “Surrey has taken this very seriously for years.” What helped get the city there, besides time, was also a marked change in attitude. Page two of the city’s Vision Zero safe mobility plan reads: “Even one death on our streets is too many.” For James, in nearby Vancouver, these stories are hopeful reminders that other Canadian cities might finally get their priorities straight. “Remember,” she says. “A pedestrian never runs into a car and crashes and kills the driver.”

Building safer cities is about more than just preventing deaths—it’s also about livability. A 2016 study of fourteen cities in ten countries found residents living in walkable neighbourhoods, with more public transit, got up to almost ninety minutes of extra exercise per week, compared to people living in the least pedestrian-friendly neighbourhoods. We know that level of activity can boost both physical and mental health. Neighbourhoods that encourage pedestrian activity have also been linked to reduced carbon emissions and stronger economies.

Planners like James are quick to point out that cities designed for walkability are more welcoming and inclusive for all. With lower speeds and more thoughtful designs, “elderly people and disabled people can go out in the street. You can have kids on bikes,” she says. “It just gives a sense of sociability and movability.”

Based on our car-centric history, Sorensen says, implementing Vision Zero has to include more than adding senior safety zones and reducing speed limits. “Our street design is wrong for people who are not in cars,” he says. “We need to redesign it so that nobody will ever get killed.” He says in places where the number of vehicle-induced injuries have been reduced, it wasn’t introducing signs for lower speed limits that did the trick, but rebuilding the city’s infrastructure. Drivers, says Sorensen, pay less attention to speed limits and more attention to the design of the road. Wide lanes and long distances between stop lights, he says, will encourage speeding regardless of the legal limit, as will wide turning radii at intersections. “Regulating the way people drive in their cars,” he says, “needs changes in physical infrastructure.”

Another reason for Europe’s success with Vision Zero, says Sorensen, is that so many major cities had much lower car-ownership rates, instead relying on high-density public transit networks. Paired with a delayed start to large-scale, automobile-oriented suburbanization (compared to Canada and the US), this meant fewer cars on the road. “There was this tradition of high-density urban life, with public transit as the main mobility mode,” he says. “They didn’t get into the suburban patterns to the same degree as Canada did.” Preliminary research led by a professor at Queen’s University, for instance, suggests that two-thirds of the Canadian population lives in suburban neighbourhoods.

In the US, though, the initiative has proven to be effective. In 2017, New York City also invested in leading pedestrian intervals at some intersections, which give pedestrians seven to eleven seconds of advance green light time before cars can move forward. The city installed over two thousand indicators, just over six times more than what it had installed previously. The same year, pedestrian collisions dropped by 28 percent. The National Association of City Transportation Officials names leading pedestrian intervals as a best practice in its urban street design guide, calling them a tool to “effectively decrease crashes and save lives on our cities’ streets.” So why don’t we do more of the same here?

“It’s 100 percent political will, and it’s really tragic,” Spieker says. In the European countries where Vision Zero has been successful, this was the recipe: governments shifted from prioritizing cars to prioritizing people. Here in Canada we’re still making that shift, and Spieker places the blame on politicians. “We have a lot of politicians [with] a high amount of social capital and they will not use it to educate residents to say, ‘This is why we need this intervention—it will not significantly destroy your life as a driver.’”

She says part of this has to do with who councillors perceive to be more likely to vote for them: homeowners who generally use cars to get around and are vocally opposed to neighbourhood change, even when it could save lives. “Politicians seize on that and it becomes a wedge issue. They say, ‘I’ll defend you from these evil cycle tracks, vote for me,’ and they make their extraordinarily comfortable annual salary while low-income people don’t have a safe way to travel around the city.”

A recent investigation by the Local found that Toronto’s Vision Zero rollout varied wildly by ward, showing success rates were directly correlated with councillors’ decisions to request certain road safety improvements. Even within a single city, pedestrian safety can change based on where you live and the priorities of your elected officials. “This is a clear public health crisis; I don’t know why that’s subject to political interference at all,” says Spieker. What’s the point in having experts, she wonders, and training engineers on road safety, if we just ignore best practices and allow people to die?

On a cloudy winter day in January 2019, forty-year-old Asim Siddiqui left his office building in midtown Toronto on foot and headed to Lawrence West subway station, just blocks away. It was lunchtime and he was en route to a meeting downtown. As he stepped into the crosswalk on a green light, the driver of a dump truck struck him while turning and fled the scene. Paramedics rushed Siddiqui to the hospital, but he died from his injuries shortly afterwards.

The only son in a close-knit family, Siddiqui was a kind and supportive brother, a hands-on father to his six-year-old son, and devoted to his parents. He often took his dad to sports games and accompanied his mother, who was undergoing cancer treatment, to each of her chemotherapy appointments, ensuring he understood the doctor’s explanations himself so he could relay them to her with clarity and empathy.

Siddiqui’s older sister Shona remains haunted by a phone conversation she had with her brother just minutes before his death. He had stopped at a Tim Hortons across the street from the subway station to grab a coffee and schedule a time that weekend for the two of them to help their niece organize her wedding. The call was brief, since both siblings were on their way to work. Shona plays it over and over again in her head, wondering if a longer conversation would have delayed his fateful trip. “I blame myself sometimes,” she says. “I didn’t hang on. I didn’t give him maybe ten seconds that I could have given him. And if I had called him back, he would have been at a red light and he couldn’t have crossed.”

For Shona and her family, navigating the legal system in the wake of Siddiqui’s death added a layer of complexity to their already raw grief. The driver of the dump truck was eventually identified due to traffic cameras, but despite the hit and run, he was never charged with dangerous driving; he pled guilty to a charge of failing to yield to a pedestrian and paid a fine of a few hundred dollars.

Shona says her family had to make several requests to the Crown’s Office to have their victim impact statements read aloud; the readings were delayed on more than one occasion. When they were finally granted permission, the driver didn’t show up to the hearing. In Canada, it’s not mandatory for drivers to be in the room for the hearings, and Shona says this left her family feeling robbed of closure. “Here we were, finally being able to get a chance to tell him how we felt, what a loss it was for us … and he wasn’t present,” she says. She calls the experience a “stab in the heart.”

Shona claims that the police told her they had footage of the driver checking the wheels of his truck when he arrived back at his workplace after the collision. He also took detours around the crash site for the three remaining trips that he completed that day, she says. Yet there wasn’t enough evidence to charge him under the Criminal Code of Canada with something like dangerous driving, which theoretically could have resulted in a year-long license suspension, or even jail time. For Shona and her family, the lack of repercussions is an outrage. “It hurts,” she says. “It’s like someone telling you your brother’s life was worthless. And we’re going to let the person who killed him get away with it.”

Drivers who hit—or even kill—pedestrians typically face charges under provincial traffic acts, rather than the Criminal Code. This means they could be on the hook for a fine and a short license suspension (as little as a few hundred dollars and a few months, if that) instead of a more serious charge such as manslaughter. Drivers who kill can be charged with dangerous driving, but that charge is often laid only if there’s excessive speed or alcohol use involved. There’s little public data available comparing the number of Criminal Code charges to the number of Highway Traffic Act charges laid in pedestrian fatalities, but all of the family members interviewed by Maisonneuve expressed surprise or dismay that the drivers who killed their loved ones received little to no penalty.

The reason for this comes down to the driver’s intentions, explains Detective Sergeant Sean McKenzie, who’s in charge of the Toronto Police Traffic Services investigative unit. A Criminal Code charge requires not only the physical act, but also proof that there was some level of intent behind it. According to McKenzie, most collisions are not planned events, although he also admits that trying to piece together the nature of a crash is an inexact science. Investigations rely on witness statements and video evidence, if possible, as well as statements from those involved in the collision itself, although it’s clearly impossible to take a pedestrian’s statement if they’re dead. Investigators rely on interpretation of physical evidence, which might include damage to the vehicle, marks on the road or on-board data from inside the car. In many cases, it’s not always clear to police what happened.

Victims—or their families—sometimes resort to civil suits, which Patrick Brown, a personal injury lawyer based in Ontario, handles. But these are unlikely to provide much in the way of accountability, he says. Even if a victim or their family is found deserving of compensation, it’s the insurance company that pays, not the driver. Brown says that drivers might have minimal involvement in the civil proceedings beyond answering a few questions. They may never even see or speak to a victim’s family, as was the case with the Siddiquis. This means that civil cases, too, can fail to offer closure.

Brown estimates that pedestrian injuries or deaths represent close to 20 percent of his caseload. Out of curiosity—and frustration—he tried to access data through Ontario’s Ministry of the Attorney General to determine how often Criminal Code charges were laid in cases where cyclists or pedestrians had been killed. When he requested the information, he only received data on doorings. “Nobody’s tracking it,” Brown says. It doesn’t seem that any other government body tracks the data, either. He was, however, able to access a review of cyclist deaths from the Office of the Chief Coroner of Ontario, which examined cases from 2006 to 2010. It found that 62 percent of collisions occurred at least in part because of the drivers’ actions—speeding or failure to yield, for instance—yet only 23 percent of those cases resulted in a charge. Data from twenty-five years’ worth of Brown’s own cases revealed similar figures.

Brown is part of a group that’s been trying to get a private members’ bill, the Protecting Vulnerable Road Users Act, passed since 2017. The bill calls for specific penalties for all driving offences under Ontario’s Highway Traffic Act that result in the death or serious injury of a vulnerable road user, including pedestrians, cyclists and people who use wheelchairs. Penalties would include mandatory community service, license suspension, and driver reeducation. It would also require drivers to attend court for sentencing and listen to victim impact statements. The bill passed a second reading at the legislature, but never made it to committee.

An act like this would not only serve as a deterrent, but provide some recourse for those left in the wake of a loved one’s death, says Brown. “They walk away feeling the system did not bring about even a remotely just result,” he says. “They don’t want it to happen to other people. They want to have some meaning to the whole situation.” Instead, most victims’ loved ones discover that there are no deterrents for offenders. “This person doesn’t even have to take a driving course. They’re back behind the wheel.”

In the UK, a harsher law came into full effect over the summer. At the time, Justice Secretary Dominic Raab said, “Too many lives have been lost to reckless behaviour behind the wheel, devastating families.” Under the new law, a driver who kills someone can be charged with up to life behind bars. The maximum used to be fourteen years, though people typically served much less time. For causing serious injury through careless driving, people can now be charged with up to twelve months in prison. In the UK, an average of eight pedestrians per week were killed between 2016 and 2021. Though the government seems committed to stopping these deaths, it’s too soon to say if the law will have an effect on the death rate.

But in Canada, statistics show that longer sentences are actually associated with a 3 percent increase in recidivism. And David Brown, a professor emeritus in the faculty of law at the University of New South Wales in Sydney, Australia, says the concept of deterrence—that is, the idea that harsher punishments will make people think twice before committing a crime—is just that, a concept not rooted in any real truth. “I call it sentencing’s dirty secret because it’s just assumed that there is deterrence,” he says. “But what the research shows is that the system has little to no deterrent effect.”

There have been cases in Canada where people have done jail time for dangerous driving, mostly when cannabis or alcohol is involved. But examples of people who’ve served carceral time are hardly success stories, especially given the still-high numbers of traffic fatalities. Aside from some kind of sanctions, what those left behind after a loved one has died on the road want most is a show of accountability. They want a chance to explain the impact the driver’s carelessness has had, and they want to see it register on the person’s face that they understand the pain they have caused. And yet there is still no system to ensure that happens.

With no guaranteed chance to read a victim impact statement to the perpetrator, and no real structure to bring about closure after losing a loved one to road violence, families are left hurt, angry, and without a sense of justice. In the meantime, design and enforcement regulations are concrete tools that need addressing. Yet road safety advocates say a culture that’s slowly becoming increasingly car-centric makes it complicated to do so.

In August 2022, sixteen Ontario organizations, including Friends and Families for Safe Streets, petitioned the province’s chief coroner to investigate whether larger vehicles are increasingly posing a greater risk to cyclists and pedestrians. They presented 2021 data from the States which found that, between 2000 and 2019, some 8,131 lives could have been saved if people were hit by sedans instead of trucks or SUVs. There’s somewhat of a precedent for their tactic working: in 2012, the Chief Coroner’s Office conducted a similar review and made twenty-six recommendations for safer roads. Those included driver education initiatives, walking strategies, multi-use community design strategies, and greater municipal control over speed limits and crosswalks. Most of them were never addressed.

Still, it’s clear changes need to be made: a recent study in the Journal of Safety Research found that taller and heavier vehicles, such as SUVs and trucks, make up only 26.1 percent of pedestrian and cyclist collisions, yet account for 44.1 percent of deaths. The same study suggests that because of their height, larger vehicles not only have bigger blind spots, but are more likely to cause more severe injuries to the chest, increasing the chance an impact will be fatal. “They have no place on a road,” says Spieker. “A handful of their users actually use the pickup truck to tow a heavy load. Most of them don’t. It’s a vanity issue and it’s a result of aggressive marketing by automakers. And the only reason they aggressively market these vehicles is because they have gigantic profit margins.”

This winter, Toronto’s snow removal fleet will be augmented by cement trucks moonlighting as plows: thirty-three of them will be outfitted with plow blades and operate on city streets. According to the CBC, city staff say these vehicles are “industry-acceptable” and could help save the city money. City council, though, was not informed of this change; it was allowed to go ahead without approval. Friends and Families for Safe Streets spoke out against the vehicles, calling attention to previous fatal collisions caused by cement trucks in the city. Spieker says safety measures like side-guards on vehicles to prevent people from being pulled beneath them, as well as a two-person crew per vehicle, will be necessary for the plan to move forward.

But regardless of a vehicle’s size, the relationship between a pedestrian and a car is always dangerous when it comes to physical impact. Sahil Gupta is an emergency department physician and trauma team leader at Toronto’s St. Michael’s Hospital. Data compiled by the hospital’s trauma program shows that over the last eighteen months, nearly one in ten major trauma cases in the emergency department was caused by a driver hitting a pedestrian.

Gupta, who commutes mainly on foot or by bike, sees the fallout of collisions like this on a daily basis. Cars are far heavier than people, he says. “And when you add speed to that, it changes the physics altogether.” Pedestrian injuries, even when they occur at low speeds, can be devastating, he says, ranging from head or spinal cord trauma to lower body injuries that can impact the patient—and their caregivers—for the rest of their lives. Gupta knows that for every patient he saves, another one is about to be hit. “These are, at the end of the day, preventable injuries in my mind,” he says. “It won’t be the hospital that changes it. It’s policy or city infrastructure that changes it.”

Making change will depend on a shift in culture, and right now, in Toronto at least, the culture between cyclists and drivers is an increasingly tense one. This summer, police cracked down on cyclists in High Park, a popular, sprawling green space in the city’s west end, ticketing people for infractions such as going over the speed limit. In early August, a cop reportedly hit a cyclist with their SUV just outside the park while driving around ticketing people. The cyclist was using the bike lane. Now, there are calls for the city to reduce police presence in the park.

Clearly, despite Vision Zero efforts, no Canadian municipality has come close to whittling down the number of deaths to zero. It doesn’t have to be this way. Cities can be built, or changed, to prioritize people over vehicles. Edinburgh has done it. Oslo has done it. Closer to home, Edmonton and Surrey are working on it. And that’s not only because of political will, but because of people like Persaud, who have been pressuring governments to make changes. Making progress will require changing the way we see the issue—shifting from “deaths are inevitable” to “deaths are unacceptable.” Once that’s done, we’ve seen full well the number can be set to zero.

As Persaud prepares for her litigation, every milestone she sees another young woman hit serves as a reminder of her own loss: hearing about her daughter’s friend giving birth, or watching her niece head off to university, and knowing Salickram has missed so much of her cousin’s life. Persaud has also become an advocate for safer pedestrian conditions, something she admittedly didn’t give second thought to before her daughter was killed.

“This isn’t just a grieving mom issue,” Persaud says. “Because at some point in time, we’re all pedestrians in some way, shape or form. This needs to be everybody’s issue, and everybody needs to step up.” ⁂

Lana Hall is a Toronto-based writer interested in business, labour and urban politics. Her journalism and essays have appeared or are forthcoming in the Globe and Mail, the Walrus and Spacing Magazine.