Images courtesy of the Smithsonian, the Library of Congress, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Met and the NYPL.

Images courtesy of the Smithsonian, the Library of Congress, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Met and the NYPL.

Outside the Frame

Photo technologies have always been blighted by biases, but creators of colour nonetheless find ways to express themselves.

I grew

up in front of the lens, but not in a Mickey Mouse

Club kind of way. My father, a trained cinematographer and photographer, was

always armed with his camera. He used it to preserve life’s major memories,

like holidays and graduations, but mundane moments too: Sunday breakfast, mom’s

hydrangeas blooming in the backyard. Those lucky enough to be captured quickly

recognized that, to him, the camera was an extra limb that he flexed often, one

used to freeze subjects in time and encapsulate them in a frame. As he shifted

to digital photography, I became spellbound by his ability to alter and enhance

his subjects. He’d experiment, dulling backgrounds in a black-and-white wash so

that the only part of the photo in colour was us. Where other photographers

failed to capture the beauty of my mother’s skin tone, my father succeeded,

patiently waiting for sunlight to kiss her cheeks at the right moment. Then,

he’d edit it to ensure she looked as vibrant as in real life.

As I got older, I realized my father’s artistry contributed greatly to how I saw myself and people who looked like me. In his eyes and through his lens, we were all beautiful; and we remain so, on the walls of the house I grew up in. These walls are filled with faces—hues of brown and black cloak cheekbones, sharp and plushy. Ivory smiles glint brightly through full lips and ebony skin. Doe eyes glisten as they follow you from room to room. When I recall my childhood, photography was always a place where I knew I could be seen. From my dad’s expert lens to the printed photographs of well-moisturized, happy Black people in my grandmother’s Essence magazines and the smiling models on the boxes of hair products in the beauty store, images communicated to me what it meant to be Black and beautiful and accepted for it. As I aged, the technology through which we create and share images progressed and shifted, providing new mediums that shape not only how we express our identities, but how we recognize ourselves and each other in everyday life. Although the prejudices and biases of the world we live in are inherently baked into the technology we use to capture each other, artists of colour still find ways to showcase their identity through beautiful, imaginative innovation.

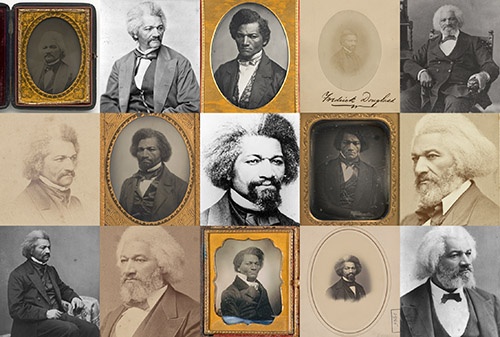

The mid-nineteenth century saw the invention, and quick popularization, of photography. This novel technology redistributed the power of image-making to the masses, many of whom hadn’t been able to afford a portrait-painter, and some harnessed its power to correct how marginalized groups were being harmfully represented in mainstream culture. At the time, racist minstrel shows were the primary platforms for white society to see what Black American life looked like. These shows featured white actors in blackface performing “comedic” sketches, contributing to stereotypes that depicted Black people as lazy, unintelligent and impoverished. For Frederick Douglass, a Black man who was born into slavery and eventually became an influential abolitionist, writer and politician, the new accessibility of film technology was an opportunity to bring forward a fresh narrative of what it looked like to be Black in America. Between 1841 and 1895, Douglass posed for over 160 portraits, making him the most photographed man of the century. His systematic approach to portraits remained the same through the decades. He’s almost never smiling at the camera; instead, his eyes are sternly affixed at the lens or to a point out of frame. This was likely to counter the ignorant, grinning slave caricature that was prominent at the time. He’s always wearing a suit and tie with no cap over his head, in stark opposition to how minstrel performers dressed. Douglass knew the power that photography has to influence our perceptions. In a lecture held at a Boston Baptist church in 1861, he told the listeners that “it is evident that the great cheapness and universality of pictures must exert a powerful, though silent, influence upon the ideas and sentiment of present and future generations.” In his portraits, he wielded that influence to combat racist stereotypes and shift public perceptions.

Photography might have made visual expression more accessible in some ways, but these technologies were, and are, shaped by our biases. In the mid-twentieth century, Kodak, one of the first companies to mass-produce photographs, had a monopoly over the photography industry. At its peak in 1976, it controlled 90 percent of film sales and 85 percent of camera sales in the US. Kodak’s dominance allowed it to influence film aesthetics; one of the ways it did this was by making accurately photographing people with darker skin more difficult. In the 1950s, Kodak introduced the Shirley card, a tool meant to establish consistency across skin tone, shadows and light. The cards included a four-by-six-inch headshot of a subject and a bar in the bottom-left corner with the three primary colours. The first card featured an image of a porcelain-skinned white woman named Shirley Page, who worked at Kodak as a studio model. Shirley cards were sent to photo labs all over the world that used Kodak’s ubiquitous printers; Shirley, and her complexion, became the rubric for skin colour in photography. Film developers would balance skin tones to match hers, leaving little direction on how to tone those with darker, redder or more tanned skin.

As film technology advanced, the ability to capture a wide range of skin tones largely did not. This resulted in those with lighter skin being perceived as easier to process, while those with darker skin were regarded as difficult and unphotogenic, their skin tones seen as dull and ashy. Often, the facial characteristics of the darker-skinned subject became blurred in a photo, with only their smiles and the whites of their eyes distinguishable from the rest of their faces. This gap in technology signalled a jarring metaphor: the inability to see a person’s humanity beyond the colour of their skin. Over the years, the original Shirley was replaced by a cast of different white women, while the first models of colour did not appear on a card until 1996. Kodak cemented a racial bias in favour of those with lighter skin tones in the photo development process; a bias that still lingers in imaging technology today.

Kodak’s empire began to collapse through the early 2000s, overtaken by companies providing forward-thinking, convenient photo technologies—digital cameras with built-in screens for easily reviewing images, phones that let you snap pics in between sending texts. Then came the smartphone explosion, and in 2010, the combination of the iPhone 4’s front-facing camera and the launch of Instagram on its App Store would radically change the face of casual photography. I was a year out of high school when the photo-editing-and-sharing app launched and was thoroughly fascinated with it; with the way its filters ironically enabled users to apply the retro aesthetic of the original Shirley-card-era Kodak to their digital photographs. I traded in my clunky BlackBerry Pearl for a skinny and chic iPhone just so I could use the app. If you asked me about my rationale for the switch, I would have told you that I wanted to express myself creatively. Ask me now, though, and I’ll tell you something different: I wanted to be seen, just like I was seen through my dad’s lens.

The selfie has been a primary character in helping amateur photographers feel seen, allowing the individual to frame themselves exactly as they see themselves in an image they shoot, edit and share with their own hands. As you control the angle, the setting and, if you wish, even the veneer through filters and apps, you can mold and reconstruct yourself like Silly Putty, redefining your features and expressions to your—and your audience’s—liking. Social media is social in nature, and anything edited or posted on a platform is done so with an audience in mind, regardless of how self-motivated the urge may seem. While this migration to digital photography might feel more liberated, freed from the Shirley card–influenced racial biases of the past, the technologies we use to edit and share our self-images are still firmly steeped in the issues of our broader culture.

The filters that enticed me to join Instagram also remind me that I exist outside of the beauty ideal that the application perpetuates. One night, in bed, I angle the camera to my face through Instagram’s in-app lens. I pose for a selfie but, before I snap, I toggle to a filter labeled “beauty magazine.” I watch as my eyes slant and lift like a Hadid sister. My skin becomes poreless and smoother. My rounded nose is thinned. I swipe through filters titled “deer,” “pre skool” and “butterfly look.” They all give me freckles, a feature that would be uncommon for someone of my ethnic makeup. The filter “butterfly pretty” gives me blue eyes; I click on the effect’s page and see that it has been used in over 30,000 Instagram reels. I scroll through the public posts and notice that the majority of the users are young women, all reaching toward a promised but unattainable Eurocentric beauty ideal. In Toni Morrison’s novel The Bluest Eye, the main character, Pecola Breedlove, wishes for blue eyes to obfuscate her Blackness and bring her closer to an indoctrinated beauty; her fixation on this impossible change results in tragedy. I’m left with the question: if Pecola had an Instagram filter to give her the blue eyes she sought after, would her story have ended differently?

As we continue to make headway into this new decade, the over-editorialized beauty of Instagram is being countered by TikTok, the video-sharing-and-editing platform launched in the West in 2017 that is known as a chaotic cesspool of authenticity over aesthetics. On the app, many users have, at least ostensibly, cast away the burdens of Instagram’s manicured aesthetic. My saved Instagram photos appear as if pulled from a glossy magazine, featuring images of attractive influencers on a beach somewhere in Cape Town sporting expensive Jacquemus bucket hats, and intricately decorated cakes that look too perfect to eat on small white plates in front of white backdrops. In contrast, my saved posts on TikTok appear as though they were curated by a different me entirely: a #BookTok review where the critic’s head eerily floats above the referenced prose using an amateur green screen, a foggy video of a woman in her bathroom skillfully singing along to a Victoria Monét ballad, a short vlog on where to purchase the best lychee slushies in Chinatown captured by a shaky camera.

Despite the variety, much TikTok content has one thing in common: it appears shoddily shot and haphazardly produced, as though captured in one take with mistakes left in. A discerning mind would notice that the appearance of messy casualness on TikTok is just that: an appearance. They’d also notice the kinds of people that are excluded from this aesthetic. Although the viral content on TikTok appears more varied, more diverse, than Instagram’s hyper-curated feed, it all follows an invisible code of curation, one that’s easier adopted by, and that prioritizes, certain types of creators.

One of TikTok’s most popular formats is #GRWM, or “Get Ready With Me.” In these videos, we observe as the content creator orates to their phone’s front-facing camera. The topic could be anything, from a hilarious tale of a bad date to a video essay on the impact of artificial intelligence. As the name suggests, while the creator is speaking to the camera, they’re also going through their daily routine: putting on an outfit before heading off to dinner, applying a skincare routine before winding down for bed. Instead of a fine-tuned image like those on Instagram, a #GRWM video is stripped down to its rawest elements. It feels private, although not voyeuristic; like you’re catching up with an old friend. At first, the creator appears imperfect, unpolished and very human. And then, by the end of the video, they are perfect, transformed before your eyes. A sense of intimacy reaches out to you from your screen. You, along with the rest of their viewers, become co-conspirators in the development of the image, the construction of the identity. You hit “like” to reciprocate the intimacy you feel has been shared.

When I see videos like these, in which creators affect a messy, seemingly unmade aesthetic, I’m pressed to think about who can afford to be unpolished. Who has the privilege of being dirty? Who gets to be ugly? Like Frederick Douglass’ efforts toward respectability, so much of people of colour’s work in photography has focused on being seen and presenting a version of beauty that differs from the Eurocentric standard that we’ve been forced to accept as gospel. We don’t have the opportunity to appear raw and uncouth; it’s those who’ve had the privilege of being presented as beautiful for centuries who get to do that. I rarely see a Black creator without their hair done and makeup sitting right. Instead, I see the circular gleam of a ring light reflecting in their eyes, nodding to the additional production requirements necessary for Black creators to be seen. I never show up in those damn disposable Kodaks that people leave on the table at parties to capture candid, spur-of-the-moment content. As photography aesthetics and algorithms reward us for looking unmade and unfiltered, what will happen to the respectability of marginalized people who have no choice but to present themselves as polished in order to be seen?

Within this TikTok landscape, Black creators have carved out a territory to spotlight and protect their content and self-expression, under the hashtag #BlackTikTok. Its videos have amassed over 27 billion views, while the hashtag’s official account created by the app has over two million likes. #BlackTikTok is a haven where Black creativity can flourish and easily find a Black audience, without compromising to appease the aesthetic desires of the platform. From high-quality edits of Black creators at the Met Gala to #GRWM videos that showcase a variety of Black hairstyles, #BlackTikTok breaks the myth of the monolith with its diverse and inclusive content. Creators can produce freely without having to code-switch; the image, content and personas they share are received with understanding, rather than exoticism. A mother putting her daughter’s hair in Bantu knots isn’t uncouth, it’s a beautiful display of ancestral aesthetics being passed down. The dazzling, extravagant display of Black American prom outfits and entrances isn’t over-the-top, it’s a celebration of progress.

Like Frederick Douglass and the creators on #BlackTikTok, contemporary photographers of colour take it upon themselves to frame subjects on their own terms, centering new aesthetics and types of beauty that transcend, and fight against, Eurocentric beauty ideals in images. Tyler Mitchell, an artist based in Brooklyn, is known for being the first Black photographer to shoot a cover of American Vogue—and a cover featuring Beyoncé at that. His work shows Black people in moments of joy. I’ve been an admirer of Mitchell’s photos since I saw the New Black Vanguard exhibit in New York, a masterful curatorial feat that explores what Black creativity looks like in fashion photography. But it wasn’t until a friend brought me Mitchell’s photobook I Can Make You Feel Good as a housewarming gift that I was able to truly digest his thesis. In the book’s photos, Mitchell captures what he calls a “Black utopia.” This landscape, a combination of fictional and real environments, frames young Black subjects in moments of unbridled freedom and unexploited vulnerability. Mitchell’s images are full of dreamlike optimism, under which stellar lighting, gorgeous fashion and sprawling scenery come together to build uplifting, unburdened scenes. It’s world-building at its finest; but even more than that, it’s reality-affirming. Within his collection, we are willed to believe that a Black utopia can exist, regardless of what our current realities depict. Elements of his world feel familiar; distant but not out of reach. It’s more tangible than Wakanda and yet more provocative than BlackPlanet, a Black-only social network popular in the early 2000s. Photographers like Mitchell correct where photography technologies have failed to vary our gaze. His photos exist in prudent opposition to the minstrel images of the 1800s, the racially-biased film processing of the 1900s and the Eurocentric beauty ideals of social media.

Similarly to Mitchell’s, visual artist and music video director Andrew Thomas Huang’s work centres people of colour in unreal environments that feel both of and beyond our time. He fuses traditional photography, filmography and 3D animation to create “fantasy worlds and mythical dreamscapes.” His music video work dares to invent a future with people of colour at the helm, from FKA twigs’ “cellophane,” which features the musician pole-dancing with a robotic, alien, human-faced flying creature, to Kelela’s “LMK,” which imagines the future of clubbing through an Afrofuturist lens. When Huang photographed queer Asian vogue performers for Lunar New Year, each subject powerfully contorted themselves into a pose with their eyes locked on the camera. Huang then superimposed rabbits on top of the image of the performer, to draw relation to Year of the Rabbit. The rabbits are a solid monochromatic shade, and stretched, bent and molded to interact with the performance of the subject. By deliberately layering traditional Chinese symbolism with modern-day Asian culture in the West, Huang centres the Asian diaspora, using contemporary photo technology to bring the beauty and traditions of people of colour to the forefront.

With photographers and artists like Mitchell and Huang behind the camera, the idea of what’s beautiful in images is widened to a spectrum that makes room for all types of beauty, not just a standardized, Eurocentric one. This expansion works synergistically with advancements in technology. As photography tech continues to evolve and change, it may not leave behind the biases of its predecessors, but marginalized creators nevertheless continue to find ways to use it to express and affirm our identities, and to speak back against the dominant discourses that pervade aesthetics and beauty. As the aperture for what is beautiful continues to expand and contract, our arrows collectively point toward better representation. Whether it is a more truthful, comprehensive way of portraying ourselves online, or more equitable imaging technology, we all want to be seen.

I think back to the images on the walls of my childhood home and recall an early portrait my father took of my mother. The image is beautiful and clear. Her smile is bright. From the quality of the image, you can tell it was taken by someone who loves her. And if you study her smile closely, you will find that she is in love with the person behind the camera, too. ⁂

Brendon Holder is a Canadian writer based in New York with work in the Globe and Mail, Electric Literature, the Drift and elsewhere. In 2021, he was named a fiction finalist for the Metatron Prize for Rising Authors. Read more of his writing in his newsletter LOOSEY at brendonholder.substack.com.