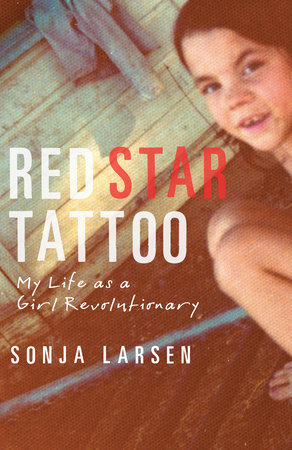

CanLit Book Club Episode One: Sonja Larsen's Red Star Tattoo

Red Star Tattoo: My Life as a Girl Revolutionary by Sonja Larsen is a debut memoir that details her tumultuous childhood on and off of communes, and her induction as a teenager into a communist cult led by a mysterious leader known as “the Old Man.” Larsen’s young life is shot through with equal parts hope and tragedy, idealism and disillusion. In the first instalment of their Maisonneuve Blog book club, Andrea Bennett and Kim Fu discuss.

Andrea Bennett: Part of the way you and I talk about books comes from having gone through an MFA together. Like a post-publication workshop. In nonfiction workshop, we’d talk about a central character. But once a book becomes a book, and you’re not sitting in the same room as its author, is it weird to talk about a “central character” because you’re really talking about someone’s representation of their life? Can you talk about “character development” when Sonja Larsen is a real, living and breathing human?

Kim Fu: Of course. You said it yourself—the author has created a representation of themselves and their life, which is an artifice. If you had met her, and you had said to me later, “Ah, she’s a really nice person,” that’s a very different thing than dissecting the art she has created, the version of herself in this book.

AB: Okay, that’s settled then. So the central question of the book, for me, is how did Sonja Larsen the character end up a member of a communist cult in Brooklyn? How did she come to believe so wholeheartedly in a cause at the age of eighteen that she dedicated her life to it?

KF: I don’t know if there is a nice arc like that. That’s not how the book is structured. I don’t think you’re supposed to read the passages about her life before the cult as a direct explanation. I think you’re supposed to read it as, these are just the things that happened to me. Which is obviously untrue, as all writing is selective, but it’s the way a lot of memoirs work. Do you think Sonja Larsen wanted this to be the central question of the book, or is this just the main question you walk away with?

AB: It’s my central question. You’re right in that Red Star Tattoo reads like a "true memoir" in the sense that it covers basically birth to early adulthood, with a short epilogue that contextualizes the preceding 300 pages. I feel like some of what appears in the epilogue could have been peppered throughout the book. The epilogue is where we get that contextualization, or meta-analysis, or analysis of what we just read. But when we’re reading all of the life events, we’re just experiencing them along with the character, with Sonja Larsen.

KF: I’m of two minds about that. I feel like she did a really good job of capturing her mindset at the time. The voice of the book for almost all of it, until that epilogue, is really vulnerable, credulous and naïve. On the other hand, it gets a little painful after a while. I wanted her to be angry. I wanted her to analyze it. I wanted something more than staying so close and so true to the mind of a young girl. A teenager always thinks they’re smart and mature and they understand what’s happening around them. The worst things that happen to Sonja in the book are regarded with a very young person’s inability to process—numbness or clichés because that’s all you have to reach for at that point in your life. Though it creates an interesting kind of dramatic irony, the difference between the way the reader is seeing this situation and the way the character is seeing the situation, it’s hard for that to be the reader’s way in. I don’t really know how she feels about these events by the end of the book and I really want to. I want an adult perspective on these events.

AB: Maybe she doesn’t or didn’t feel angry. It’s hard to say. There’s only so much that it’s fair to read into what she as a person wants or doesn’t want. We can infer things about her character based on what is presented to us. We witness the character being sexually abused, for example, as a kid and then as a vulnerable teenager (even though the adults in her life seem to view her more as a peer), and because of the timeline of the book, even though she’s chosen not to have a parallel narrative of contextualization, you do eventually see some of the aftermath and her reactions as her life unfurls.

One of the people who abuses her is her mother’s boyfriend, when she’s a child living on a commune with her mom. She seeds some stuff in before that. We see that the boundaries on that commune are in some senses nonexistent. At one point Sonja walks in on two adults having sex and they ask if she wants to stay and watch, because there’s this idea that children have been too shielded from sexual activity. Sonja also talks about Hacksaw, a donkey the commune purchased that she describes as sex-crazed. (I can’t imagine being as careless as the parents on this commune! They keep adopting pets for the kids and then, like, eating them out of hunger and desperation.) Anyways, she writes, “Sex made everyone crazy, not just Hacksaw. Even inside me there was a magnet that drew men in, though I couldn’t feel it, couldn’t see it. Sex was the creepy-crawly feeling of Karl’s hand on my thigh a few months later, like a wasp that could not stay away from fruit.” This is before she really depicts the abuse. Then, later, when she’s a teenager, she writes about sending her mother an angsty poem about the boyfriend’s abuse. We see her reactions occur in real-time. I guess we miss out on the ones that maybe came later for her, after the narrative of the book has wrapped up.

I did wonder if part of what drew her to the leader of the cult—this agelessly old creepy smoking man—was the ways in which her boundary-less childhood hadn’t prepared her to quite understand what was and wasn’t appropriate when it comes to relationships that have clear and obvious power dynamics. We as readers get to see that relationship in the context of a pattern of other relationships, but we don’t—you’re right—get to see how adult Sonja thinks about it, feels about it, has processed or not processed it.

KF: The idea that children shouldn’t be shielded from sexuality had some play in that era. It’s not like the people on the commune invented that idea.

AB: So you think it’s arguable whether or not that’s abusive or a bad environment for a kid, or a product of the times?

KF: No, I feel firmly that it’s an abusive, unhealthy environment. In the book, it escalates to something inarguable, but for me, the adults were not just stupid, they were doing active harm to these children. Now that we’re one or two generations past, we know how this philosophy actually worked out, and how these kids feel about it as adults. Everybody knows people who had parents like that.

AB: It allows people like Karl—her mother’s boyfriend—to exploit the situation.

KF: Returning to your question about why she ends up in the cult in the first place, what drew her, I think the book makes a very strong ideological argument. As a teenager, she faces the very basic questions that all teenagers do about the dysfunction of the world around them, about capitalism and social injustice. That so many people are suffering. What do you do? The party gave her an answer. And it was framed that way when she first encountered it. The cult was on a list of charitable things that young people could do.

AB: I get that. I recently read Charles Demers’ book The Horrors, and he talks about joining The Communist League, the Canadian counterpart to the American Socialist Workers Party, as a teenager … but you see him as a teenager being equal parts involved and disillusioned, and understanding the party members around him, who are much older, are in fact just flawed, messy adults who have a habit of spitting bits of rice or pita as they speak. And then there’s Carmen Aguirre’s book, Something Fierce: Memoirs of a Revolutionary Daughter. Aguirre grows up in Chile, and she and her family flee to Canada when Pinochet comes to power and things get hot for her parents. They go back as a family seven years later and Aguirre writes about fighting to overthrow Pinochet’s rule. Demers’ self-awareness and the concrete goals of Aguirre’s fight made them more relatable to me. I didn’t understand how Larsen could find herself in 1980s Brooklyn and be visualizing armed revolution under a sad old man.

KF: I think it’s more like this: there’s an abstract problem that you’re conscious of, that makes it hard to exist, that is a source of tremendous despair. Someone presents you with an abstract solution, an alternative system at a grand scale. And then they tell you: the way from A to B is very complicated, we’ve got it figured out, how you help is by chopping potatoes. I understand why that’s seductive. That’s something real that you can do. You can chop some fucking potatoes, and believe that in some small way you’re helping. Especially if you’re an eighteen-year-old.

AB: I did chop potatoes. I was part of an anarchist anti-poverty organization and I chopped potatoes with the goal of feeding myself and other people. We had concrete short-term goals: eat dinner, help someone not get evicted. But Larsen and her comrades are chopping potatoes so that they can maintain this house because they’re working towards this larger, massive revolution. I would not sign up for that if I didn’t understand exactly how it was supposed to happen.

KF: To me, it’s very similar to “God works in mysterious ways.” It’s clear to any given twelve-year-old that the problems are staggering and systemic. A child can see that these problems are so large as to be almost certainly unsolvable, and the answer “well, it’s solvable, you’re just too small to understand it, but you can still be part of it”—I think it’s a religious answer, and it’s clearly a very compelling answer to lots of people. That’s the basis of Christian faith, and that’s the basis of the communist organization Larsen was in as well. In both, it’s considered an act of humility to say, “The world is fucked up beyond my understanding.” And that’s why “God works in mysterious ways” and “here are these abstract solutions, trust me, we’re on it, chop some potatoes” are similar castings.

AB: Never will I ever trust someone’s word on any of that. They have to be able to explain it to me. I guess religion has a priest or a pastor or an imam or a rabbi, whatever, who helps interpret for you God’s words and God’s ways to the extent that they’re interpretable. And maybe they’re not, in certain circumstances. But I feel like political systems should be interpretable. And the analogy for the priest is the Old Man.

I wanted to understand why people would follow someone like the Old Man, and I don’t. I guess we live in a post-post-modern world now and there’s been such a retrenchment towards making sense. The Old Man speaks in these complex dialectics, and he’s the intermediary between study and action for Sonja Larsen and all the other people who follow him. I don’t understand. Do you understand what makes him appealing? How does he inspire people?

KF: He’s the first person to ever ask Sonja for the totality of her story, and to discuss her place in her story, the meaning of her life. I have this theory why acupuncturists, chiropractors, homeopaths and holistic practitioners are so popular—it’s because they’re the only people who say, “Tell me everything that’s wrong with you, and I can fix it.” The Old Man offers this to young girls, isolates them and controls every aspect of their lives. He gives them structure, he gives them an answer to basic existential despair. There’s a whole system built around him that sucks you in and keeps you there. I don’t think that he necessarily needs to be that appealing or charismatic of a person. They first hear him as a voice on tape distributed to their local communist chapters. They hear him as this completely abstracted central wisdom, very much like God. And then you just get deeper and deeper entrenched in a system that literally doesn’t let you leave. There’s also all this metaphysical bullshit she was fed on top of all that.

AB: Dialectics.

KF: It wasn’t just politics. It was also metaphysical explanations for why everything is, including why she had experienced so much suffering up to that point, and how she could be in control of her suffering going forward.

AB: What a horrible time in history. Don’t feed people dialectics to explain their abuse!

KF: Religion does the exact same thing. It also gives you an explanation for your suffering and puts you in control of your future. And there’s ways of talking about these ideas so they sound like answers. That’s why people say “every young person with a heart becomes a communist”—the tenets of communism seem intuitively logical and fair, when you’re more moralistically simple, when you believe in fairness and a fair universe.

AB: I still believe in fairness and a fair universe!

KF: How do you deal with that? How do you live?

AB: Right now I’m eating Nutella out of a jar.

Kim Fu is the author of For Today I Am a Boy: A Novel and How Festive the Ambulance: Poems.

Andrea Bennett is the Senior Editor of Maisonneuve.

Send your thoughts to [email protected]. For our next instalment, we’ll be opening up our book club to other readers. Details to come!