Thanks But No Thanks: A Conversation with Emily Davidson About Pitching

Emily Davidson and I are both graduates of the University of British Columbia’s MFA in creative writing program—in fact, we were in the same year. She’s currently seeking publication for her first two books—a collection of poetry and a novel. Emily and I have received a few similar (and similarly irritating) rejection letters of late, so we got together to talk about the process of submission, rejection and acceptance—our likes, dislikes and never-agains.

Andrea Bennett: Let's start at the beginning: could you tell me about how you keep track of submissions?

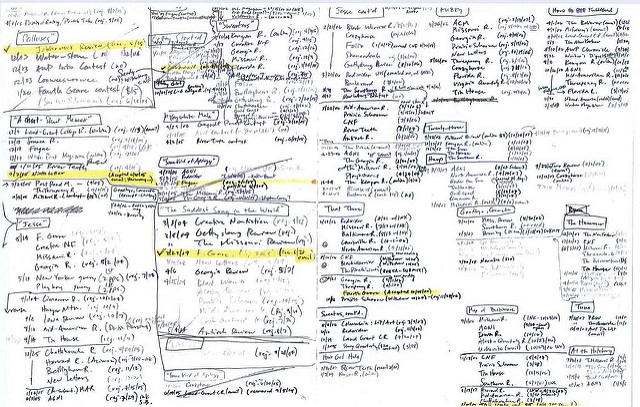

Emily Davidson: I’m currently in the process of submitting both individual poems and two completed manuscripts. I keep track of shorter-form submissions in a very basic Word document, with the headings "Accepted," "Rejected" and "Under Consideration" keeping things organized. Since manuscripts feel like different animals to me, I have a separate document where I track my book submissions.

AB: Do you have a sense of how many pieces you've submitted over the past few years? Do you keep track of which pieces have been accepted and rejected, and, if you do, would you mind sharing the breakdown of your numbers?

ED: I'm going to do a count, hang on. Okay, results are in: I've had fifteen individual poems placed in either literary magazines or anthologies, and 159 rejections of individual poems from the same. That's about a 10 percent success rate, isn't it? I've had one fiction piece published and four rejections—I'm tracking better for fiction. I've had one piece of creative non-fiction accepted and one rejection. And my poetry collection has been seen by seven publishing houses so far. After looking at these numbers, I don't know whether to be encouraged or start researching alternate careers.

What about you—what do your numbers look like?

AB: These days, I write nonfiction and poetry, but I used to write fiction, too. I submitted 101 things—fiction, poetry, nonfiction—between late 2009 and mid-2014. This includes contests. Fourteen submissions were accepted or partially accepted (as in, a poem or three from a larger batch), and three were shortlisted for contests. (I've never won a contest!) That's eighty-four rejections between 2009 and 2014. I haven’t been tracking myself as carefully lately because I’m often pitching nonfiction to magazines and A) the response times are much faster; B) pitching requires a more active approach.

ED: As someone working in a field where rejection is so overwhelmingly the norm, how do you process being turned down at every turn? Have you developed coping mechanisms?

AB: I used to find it difficult to process so much rejection. Our MFA year at UBC included a really talented set of people, and, almost immediately, writers from our cohort began to have things published, to win contests. I came into the program with the mindset that there was going to be a steep learning curve for me and I was going to need to bring my A-est game. As our cohort began to find their successes, it prompted me to treat submissions more professionally. I made a Google spreadsheet and started to try to look at my work more objectively. Giving and receiving workshop feedback helped a lot with that.

The MFA also provided an opportunity to work through the jealousy that can crop up when your peers are seeing more success than you. I'm not a particularly jealous person by nature, but I do tend to get down on myself. I remember talking to Ben Rawluk about compersion, which is this concept in polyamorous relationships where you're happy for your partner's happiness with another person—we talked about how this concept applied to our situation. How to cultivate writerly compersion. There's also a long-game approach to thinking about competition and jealousy—a rising tide lifts all boats! It's good if you're surrounded by talented people who know about your writerly/editorial strengths!

If I happen to feel sad or devastated about a rejection, or an unsuccessful application for a grant or a gig or a residency, I'll let myself feel as awful as I want for a day or two. My emotional range is ... broad. In the past, facing rejection, I've experienced deeply catastrophic thoughts about my life and worth. I express these feelings in the comfort of my own home, reaching out to my partner and a close friend or two, and then I get back to work. My mindset now is that there's no one accomplishment that finishes things for good or bad—writing and editing are really the only things that I want to do with my life, and to be honest I think that the intensity of the challenge they often present is part of why I’ve stuck around.

ED: Is one kind of rejection letter better than another?

AB: If it's a pitch that's being rejected, it's nice to get a bit of feedback about why, particularly if I've worked with the editor before. I've also had editors suggest outlets that might be a better fit, which makes me feel like, Hey, good looking out! But I'm just as happy to receive a form rejection, or a polite “No thanks.” If an editor says something like, "We don't love these pieces but we like your work and we'd like to see more of it when you've got new work ready," that’s great, too.

What I dislike very strongly is to have an editor offer encouragement to "keep going with it!" as if I'm the little train that could. And some of the personalized rejections that come from literary magazines and publishers include notes like this. It has only ever been male editors who've written me these kinds of notes—men in their forties, fifties or sixties. Here's how I feel: I'm your peer. We're adults. You didn't like my work and that's fine. "Keep going!" only serves to shore up some kind of Lord King God barometer of taste for them—it's not helpful for me at all, it just reinforces what that guy thinks is the power dynamic between us. In an industry where we're supposed to be thinking about the various ways in which our words communicate meaning, it's remarkably un-self-aware.

Are there kinds of rejection letters you'd prefer to receive, and others that make you want to paintball someone's house?

ED: I've received rejection letters so nice it's like I've been kissed on the cheek by my high school crush. The "we really believe in your work, we just didn't have space for you" letters, the "our whole office read your manuscript with pleasure" letters. In my rational moments, I know that publishing houses and magazines have many criteria determining whether my book or poem is or isn't a good fit, very few of them within my actual control.

The rejections I struggle with are ones that tell me to do something I don't quite understand. I've been recommended to work on structure—which is great, but what element of the structure? My pieces lack tension—could you give me an example? An editor’s yardstick for what makes a good poem may not be the same as mine, and we're not always speaking the same language when it comes to revisions.

And the ones that make me spit fire are any time anyone talks down to me. I may be asking for you to consider my work for publication, and you may not find it to your taste, but it doesn't mean that I haven't been at this gig purposely for a good handful of years. I've invested time in knowing my stuff. I once received rejection from a university press where the reviewer was my peer—still a student—and described one of my pieces as "decent." I nearly Godzilla-d my apartment building.

I am apparently a terribly proud and wrathful person.

AB: How do you deal with rejection?

ED: My coping mechanisms have improved vastly since my early rejection days. I tend to internalize rejection as a judgment on my inherent value as a human being—"such and such magazine dislikes my writing, so I should probably go jump in a well forever." The cure for this kind of devastation seems to be perspective. I now know to do two things upon receiving rejection: 1) Feel as bad as I want to for a bit, and, depending on how much I'd wanted the acceptance, eat an entire bag of mini-marshmallows in my pyjamas. 2) Reach out to one or two people who know me and my work, and can speak to its strengths. Rejection tends to feel permanent; good friends make it temporary.

I really appreciate your bringing up comparison, because it is tough in this business to watch other people achieve what you're aiming for. It is so easy to equate other people's successes with a depletion of opportunities, instead of what it really is—a sign that the kind of work we want to do is actually still possible. I've put in a lot of time reaching for the feeling of being genuinely thrilled for someone else, and have found that if I reach often enough, it becomes authentic and more readily available to me the next time I need it.

You're in an interesting position as someone who sees both sides of the magazine world—you're both submitting your own work, and accepting other people's. Does this make either process easier? Harder?

AB: Being a writer has informed my approach to submission response as an editor: my goal is to try to be as clear and as quick as possible, and also to avoid not responding, because I'd personally rather hear "no" than silence. I think that being an editor probably also informs the way that I approach pitching—be the pitch you want to see in the world! I'm not sure if it really changes the way I submit poetry, except for the fact that it's easier to visualize an actual person on the other side of the letter or email or Submittable screen. At the very beginning of my career, I wasn't necessarily discerning about what I sent in—it all seemed very mysterious and impossible anyway—and while I don't regret that, I'm at a point now where I want to take a little more time with my work, and make sure that it's up to my own evolving standards instead of relying on editors as gatekeepers.

Do you have recommendations about submission strategies or coping strategies for people who are just starting out, or people who are in that mid-point, where they have some journal publications and anthology publications, and they're now starting to approach publishers? Is there anything you wish someone had told you?

ED: When you first start into the process of submitting, it can be daunting. I remember feeling like lit mags were these bastions of excellence and I was this weird plebe with a pen.

If I were to offer a tip, it would be this: in the beginning, have someone look at your work. This could be a professor or a friend, a writing group or an online mentor. UBC's Booming Ground program is a fantastic resource for emerging writers. In the early days, I sent out nothing that hadn't been shown to at least one other person—someone who cared enough about writing to be able to say "that third stanza is bogging you down" without completely crushing my hopes and dreams. Good outside perspectives have been key in keeping me afloat, and making sure my work is print-ready. If at all possible, find your people.

Once you've assembled a small stockpile of vetted writing, it's time for the mantra I have had shouted at me—and have gone on to shout at others—and have found strangely cathartic at high decibels: submit. Get your pieces together and send them. Pick your favourite literary magazines, check their submission guidelines and get out the manila envelopes. Write cover letters that are clear and professional—include some biographical information, but don't be weird. Begin a tracking system—many writers use Duotrope, I use the aforementioned high-tech Word document. Expect that responses will take up to six months, so try to get more than one set of work in rotation. Get a rejection? Take that story, give it a hug and pop it back in the mail. On to the next. Submit, submit, submit. Submitting is the writerly equivalent of every cliché you've ever heard about getting back on the horse, brushing yourself off, putting your money where your mouth is. All forward motion counts.

Do you have any rituals surrounding acceptances—any way you celebrate? Because we should probably talk about some of the good stuff or we're going to put people off.

AB: I wish I was a more ritual-oriented person. I tried to get into lighting candles around Christmas time, but it turns out they trigger my asthma. When I receive an acceptance now, I try to give myself a moment to be in or with that emotion—satisfaction, happiness, whatever. If it's a larger type of celebration—the flipside of crying on the floor in my apartment—I buy a bottle of prosecco.

Do you have rituals surrounding acceptances? I feel like you might be better at this than me.

ED: There is usually a strange dance involved when I get an acceptance letter. Something between a shimmy and a wiggle. But alone, because, well, yeah. I'm not a dancer.

Otherwise, I'm actually fairly ritual-free. I tend to celebrate quietly at first, because odds are the magazine that just accepted me has turned down three of my friends. (This is what happens when all your friends are writers. You've been warned.) I do have a habit of texting my parents, who are wonderfully practiced at patting me on the back and telling me I did a good job.

We should come up with something we can both adopt as our new acceptance tradition. I'm not big on prosecco—maybe new socks?

Emily Davidson is a writer from Saint John, New Brunswick, working in Vancouver, British Columbia. Her poetry and fiction have appeared in magazines across the country, and her work was most recently anthologized in The Best Canadian Poetry 2015. Her nonfiction was recently featured in the anthology Boobs, which came out with Caitlin Press.