What We're Supposed to Write: An Interview with Naben Ruthnum

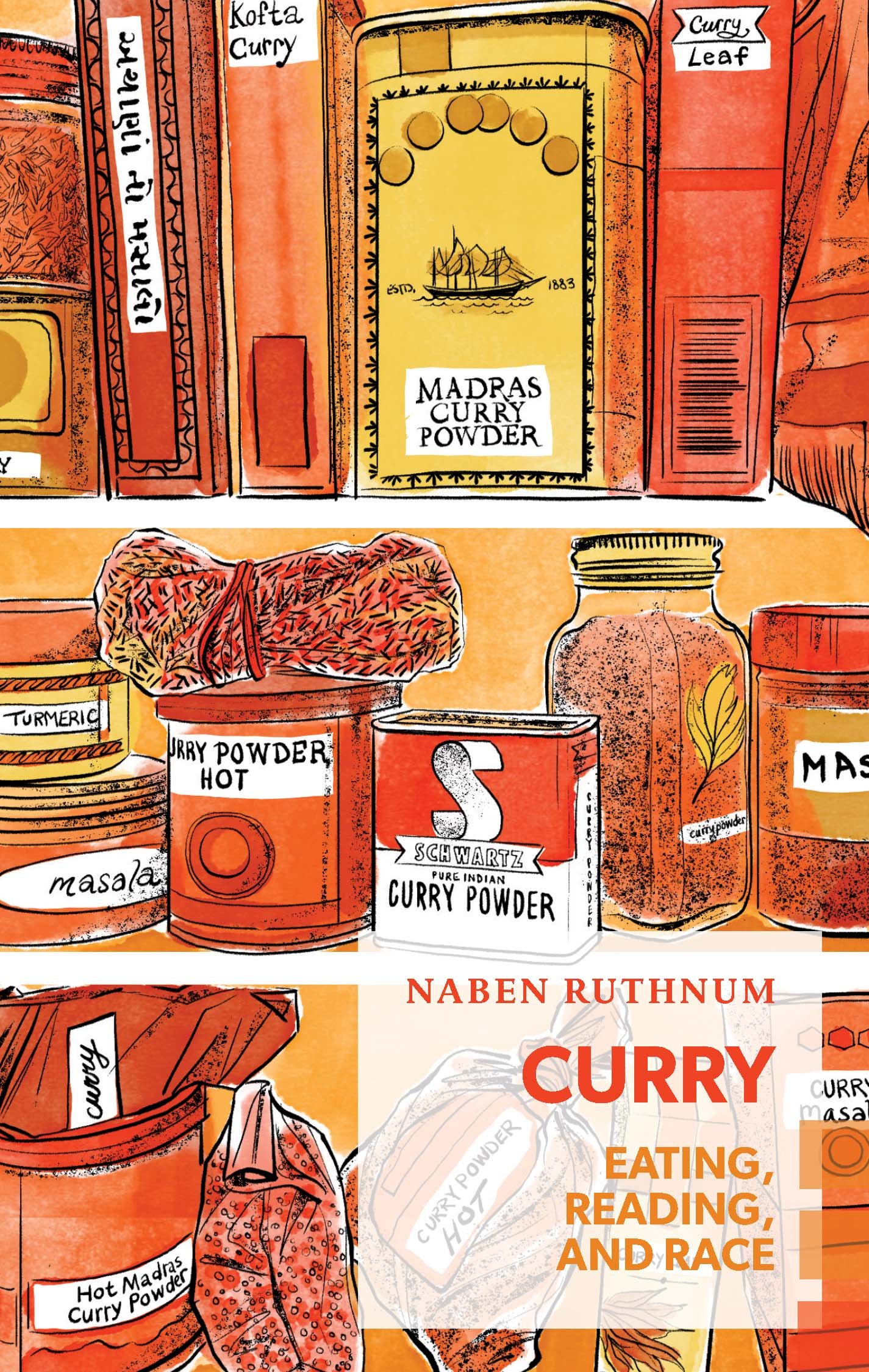

Naben Ruthnum’s Curry (Coach House/Exploded Views), a book-length essay in three parts—Eating, Reading and Race, plus an introduction and coda—analyzes books, pop culture, recipes, colonial history and Ruthnum’s own experiences to deconstruct accepted narratives about the South Asian diaspora, half-disparagingly referred to as “currybooks.” With unsparing wit and skepticism, Ruthnum interrogates the expectations placed upon artists of South Asian heritage, and the troubled concept of authenticity. Maisonneuve Associate Editor Kim Fu spoke with Ruthnum about how this book came to be, his imagined audience, and why we shouldn’t hesitate to criticize other artists within our communities.

Kim Fu: What led you to Coach House Books, and

the Exploded Views (EV) series in particular? What made you feel like it was the best fit for this project?

Naben Ruthnum: I’d read Shawn Micallef and David Balzer’s EV books before the idea of writing for the series came to mind, and when Emily Keeler became the series editor, my friend Julia Cooper was the first author she worked with, resulting in the excellent The Last Word. Emily asked me if I had any ideas for a book that would suit the series, and I didn’t, until I thought about it a bit. The novels I’d been reading for the few months prior to coming up with Curry, along with general thoughts about South Asian identity that I’d been batting around with Rudrapriya Rathore and others, coalesced into a very sloppy but quite excited pitch that I sent to Emily. I think the broad range of subjects and varied approaches I took to writing about them made EV an ideal fit, as the short length of the manuscripts in the series lent itself to a certain level of depth balanced with a certain level of humour.

KF: Can you talk a bit about how Curry relates to your larger body of writing, and how you wanted it to fit into the arc of your career? The book’s coda makes it seem like you wrote Curry with a great deal of intentionality in this regard.

NR: It’s a bit of an accidental mission statement, I suppose: I think that the parts of the book that are most worthwhile are my thoughts on other peoples’ writing and cultural artifacts, but I can’t deny that the impetus behind a lot of my opinions and arguments lies in establishing that I intend to write across genres and am highly uncomfortable with any expectations being placed on what I produce. I’m not self-important enough to imagine an audience that is determined to see me, specifically, write a certain type of story forever, but I think that writers at any career stage are subject to expectations that can be frustrating.

KF: How did the process of writing Curry compare with the process of writing your forthcoming crime novel, Find You in the Dark, or to your fiction-writing process in general? Were there similarities, or was it a wholly unrelated beast?

NR: I’d say completely different. I don’t come from an MFA background, but I did do an academic MA, and writing Curry felt much like writing a second thesis, but without the particular demands of scholarly writing.

KF: To me, the voice in Curry comes across as conversational, or even argumentative—that is, as though it’s addressing an auditor, or responding to an opponent. Did you have an imagined audience while you were writing it?

NR: I think I had a few different audiences in mind—writers like me, certainly, who feel constrained by expectations to repeat certain narrative conventions that are based on what people of their race/gender/orientation are “supposed to write.” Also, readers who enjoy “currybooks,” both good and bad—I wanted them to think about what it is they got out of reading these narratives, and whether there may be stories that they are missing because they enjoy returning to the strums of a familiar tune.

KF: What has the response to the book been like so far? Has any of it surprised you?

NR: Because the book falls into a netherzone between food writing and cultural criticism, it’s been more successful than I would have expected in attracting attention from media outlets like Vice and drivetime CBC radio shows, who I wouldn’t necessarily have expected to be talking to—and the response has been positive. I’ve run into appreciation for writing in a (hopefully) funny tone and bringing up identity issues in a way that’s both personal and non-prescriptive.

KF: A significant feature of Curry is your criticism and sometimes outright dismissal of specific books—for their part in a larger, dominant narrative, but also their literary quality. Even as someone who writes book reviews, I often found this startling and even a little ballsy, especially since you’re necessarily mostly taking apart work by other brown and diasporic writers. (Criticizing white writers like Elizabeth Gilbert felt less fraught somehow.) Did you struggle with this? Do you feel different responsibilities or pressures when talking about books by writers of colour versus white writers? (Or maybe that’s condescending, and art is art?)

NR: I did try to be careful to avoid beating up on anyone’s work in the book, at least not in a cheap fashion—I can think of one book that I did say stinks, but for the most part, I tried to let excerpts from books that I may have liked less speak for themselves. There were certainly essayists that I talked about whose points I disagreed with, or fiction writers who spent a lot of time on tropes that I consider tired, but in those cases, I stuck to pointing to what I disagreed with in the work, without chimp-attacking the author.

But I think it’s really important to be able to speak critically of the work of fellow writers from your racial background without being accused of “breaking ranks” or some similar shit. We’re adults, engaged writers and critics, and should be able to discuss each others’ work openly without it seeming like a betrayal. Being critical of a work in a responsible way means that you’re first taking the work and the author’s intention seriously, and that can’t be bad.

KF: Have you or your views changed as a result of researching and writing this book?

NR: I certainly learned that I’d been dismissive of books that I thought were completely reliant on telling the same ol’ currybook story again, but turned out to have significant depth and skill in their composition—I’d point to Monica Ali’s Brick Lane as a book that I had badly, and stupidly, misjudged when I first gave it a go. It reinforced to me how much I bring my thoughts and anxieties about my own writing and career to the books that I read, and that those anxieties spike when I’m reading brown writers.