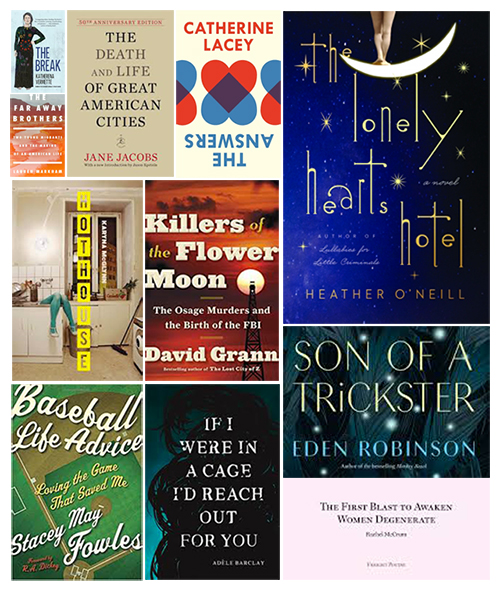

Maisy's Best Books of 2017

As

we do from time to time,

Maisonneuve asked the folks who wrote for us in 2017 to send us a few words on

the best books they read this year. The following is a snapshot of one year in Canadian

writers reading.

Son of a Trickster, Eden Robinson (Knopf,

2017)

When I went to buy Son of a Trickster early in the year, I found every store in Vancouver was out of stock. One bookseller told me that family members of Eden Robinson herself had been buying up every available copy and sending it back to the kids in their community. When I finally got my hands on it, I learned why. Robinson’s characters are so vivid, so ferocious and funny that I wanted everyone I knew to spend time with them.

The story follows seventeen-year-old Jared Martin, whose winding journey through the perils of small-town high school life takes a detour into the surreal when he begins to learn about the real world magic of his Indigenous family. Don’t let the young adult label fool you—this is a world where punches land hard, but the book never wallows, always choosing the path of resilience and Robinson’s wicked sense of humour. I can’t wait for the sequel.

—Erika Thorkelson, whose cover

story “The Language of Profit” appeared in our Spring issue.

Smaller Hours, Kevin Shaw (Goose Lane, 2017)

In the alchemy of Kevin Shaw’s debut collection of poetry, Smaller Hours, time turns liquid and looses a flood over page and mind. If—as Nick Mount has said in a lecture on Sylvia Plath—the lyric poem seeks to stop time, then Shaw’s poetry seeks to bend it. Time is one of the collection’s declared motifs—a thematic commitment announced in the title and the book’s first poem, “Clocked,” where an early encounter with death leads the speaker to discover “the story of an hour.” Time is clearly crucial here, but liquids are similarly prominent, from the prize-winning “The Flood of ’37” to the remarkable “Occlusion Effect,” where a 1990s Ontario murder mystery synchs daringly with glacial temporality. The recurring connection of liquid and time is not just aesthetic; Smaller Hours is a self-styled counter-historical project. Shaw’s stately and ornate lyric verse exhumes the queer histories lurking copiously in the military garrisons, man-made lakes and Victorian estates of London, Ontario. What Shaw does best—riding the current of extended poem-length metaphors with an astonishing, quiet dexterity—is difficult to describe without quoting entire poems. But a quick glimpse reveals that Shaw’s greatest asset is sonic athleticism: “I’m only reminded / that he and I share nothing, except / the flesh doming through its repetitions / and sleep atrophied by early morning.” Fluid and nimble, slick and slippery, this is poetry to submerge in. What a delight to drown in Kevin Shaw’s verse.

—David Huebert, whose review “The History of Canada Is a History of Oil" appeared in our Fall issue.

Things Not to Do, Jessica Westhead (Cormorant, 2017)

I believe fervently in the short story as something other than just the novel's minor leagues or a proving ground for emerging talent, and so does Jessica Westhead—or so suggests her second collection of wonderful stories, Things Not to Do. In a voice which hovers somewhere between George Saunders and Lorrie Moore, Westhead probes the absurdity inherent to the systems in which we live and toil, which sustain or punish us or both, and in which our control is limited or nonexistent—love and capitalism and climate change. She extends to her characters a sweetness and a generosity which is not mere charity, but genuine understanding, whether they are children or caregivers or cheating spouses or fast food wage slaves, and she challenges the reader to do the same. I don't know what Westhead is working on now, but I hope there are more stories in the pipe, because she's very, very good at writing them.

—Andrew Forbes, whose short story “Emmylou” appeared in our Spring issue.

If I Were in a Cage I’d Reach Out for You, Adèle Barclay (Nightwood Editions,

2016)

My first reading of Adèle Barclay’s debut poetry collection, If I Were in a Cage I’d Reach Out for You (Nightwood Editions, 2016), was slow and deliberate. Her word choice is so precise, I half-feared (and half-hoped) I was summoning something. On my second reading, I realized I was right: I felt the presence of my lost loves—family, friends, and flames—people Barclay didn’t know yet somehow rose from the past so I could confront them. And myself.

Divided into five sections, Barclay’s work lingers on the moments within moments, our personal cycles of change, and the forces that govern us all—hunger, sex, and the planets, among others. She is a deft guide to another dimension of reality that lives just below the surface of all things. The result is destabilizing in the most exciting way possible. The book is full of words I know, but that I’d never seen used this way. I audibly said “Wow” as I read it.

If I Were in a Cage I’d Reach Out for You is also deeply visceral. I felt this book everywhere in my body, and I still feel it now, though it has been months since I’ve read it. It keeps calling me back to find more clues, to get at what’s underneath Barclay’s thick, indelible witchcraft that leaves an imprint on your heart.

—Erica Ruth Kelly, whose Letter from Montreal “You Want to Travel With Him” appeared in our Fall issue.

Look, Solmaz Sharif (Graywolf, 2016)

Solmaz Sharif's Look, a finalist for the National Book Award, decenters the narratives of fighting white males of military age and provides indispensable, incisive commentary on warfare and post-9/11 America. If, as George Packer writes in the New Yorker, “new war literature is intensely interested in the return home,” then Sharif refuses to let the idea of home itself remain the static domain of white America, choosing instead to focus on the bodies that white America has torn apart. In “Drone” the speaker says, “my father was reading the Koran / when they shot him through the chest.” Readers are confronted with the absurdity and intentional violence of war—verbal and physical. Sharif speaks the language of militarization fluently, but she turns the language on itself, and in doing so, destabilizes and dissects the jargon of military force.

American War, Omar El-Akkad (McClelland & Stewart, 2017)

Omar El-Akkad's American War speaks directly to our current anxieties about war, displacement, radicalization and climate change. The dystopian future he presents is marked by the kind of violence that lingers and hardens, becoming both inheritance and curse. The book is about the self-referential impossibility of finding peace through revenge, about the ways that individuals convince themselves that war is necessary and that violence is justified. It’s about rhetoric and propaganda, anger and anxiety. Like Solmaz Sharif, Omar El-Akkad forces readers to reconsider the parameters of a war story, or what a war story truly is. At the novel’s outset, the narrator says, “This isn’t a story about war. It’s about ruin.” The expansive, fractured world of American War is not our own yet, but it is one of many that our current world could become. Ultimately, El-Akkad doesn’t offer any false comforts. Instead, he gives us violence and resilience and forces readers to ask the difficult questions about how we engage with our neighbours, communities and countries.

—Benjamin Hertwig, whose feature “Buried at Centre Ice” appeared in our Summer issue.

Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage

Murders and the Birth of the FBI, David Grann (Doubleday,

2017)

Despite the story being a century old, Grann’s book touches on so many current themes: Indigenous rights, abuse of government power, intergenerational trauma. While writing a long feature, I find it reassuring plunging into another nonfiction piece. It provides both a distraction and a mirror to your own work, and I read this page-turner by candlelight for a week straight. Grann’s second-to-none storytelling skills (he’s a writer for the New Yorker) allow the reader to piece together the whodunit of the Osage murders. While the ending is slightly predictable, it’s not the destination but the journey that counts. The deep-level corruption and generational pain the Osage murders caused resonates long after the final page, and Grann manages to capture this zeitgeist moment in American history that thrusts state law and criminal behaviour into the federal sphere. Grann doesn’t paint a romantic picture of cowboys and lawmakers, but instead humanizes the victims, their families, and even the nefarious characters on all sides, opening up a chapter of US history that’s long been buried outside of Oklahoma. Grann has a supernatural instinct to find stories no one else is writing about, free diving into the deepest parts of it, and emerging every time with an ocean pearl. This book is a revelation and a reckoning.

The Lonely Hearts Hotel, Heather O’Neill (HarperCollins, 2017)

Heather O’Neill is the reigning rock goddess of Canlit, Canada’s Lady Galadriel. Her prose is fierce, fiery, vulnerable and muscular. She creates worlds and sounds and dialogue that feel oddly familiar, yet wholly singular. If The Girl Who Was Saturday Night is a gangly, self-aware teenager, The Lonely Hearts Hotel is a grown-ass adult. O’Neill writes about two lovestruck orphans in Montreal in the 1920s, and her imaginary world feels so real and tangible as you amble along with these odd and beautiful characters that the cabarets and movie theatres of a bygone era leap off the page. This book burrowed its way underneath my skin. It’s a salve and an antidote, a scream and a whisper, a fictional incantation knocking on the historical past. The tortured relationship between the separated orphan lovers haunts the reader throughout the book, and O’Neill’s unwillingness to take shortcuts builds tension throughout. It’s bawdy, naughty and strange at times, all buoyed by an unmistakable cadence that can only belong to O’Neill. The denouement struggles to connect to the whole, but that’s merely a small piece of paint chipping on the top corner of the canvas. There’s simply no living writer who writes about Montreal like O’Neill.

—Adam Elliott Segal, whose cover story “Black Market Babies” appeared in our Summer issue.

The

Answers, Catherine Lacey

(Granta,

2017)

The Answers by Catherine

Lacey was a book I didn’t buy. And isn’t it often the case, that the book you

hadn’t been looking for is the book that you will love the most? I took the

book with me on a train and read it all night. Everyone around me fell asleep

in the dark, but I kept the light on. When I looked out the window, there was

only the dark, and the reflection of my face. I had tried to see beyond that,

but there was nothing.

When I was very young, I thought I knew what love was. That it was simple. You either knew or you didn’t. And I refused to read about it, thinking that love was something that happened to other people. And then when it happened to me, for the first time, the person I loved told me it wasn’t real. That what I felt wasn’t real. I only thought it was because I hadn’t encountered it before. But I knew what I felt. Its intensity, how profound it was. It was real to me. But it didn’t matter, because it was not real to the person I loved. I never went back again. I knew what was real and I didn’t want to be with someone who didn’t see it.

When I read The Answers, I thought about this person. This person who said what I felt wasn’t real. This person who did not call what I called it, love. Her book made me see that it doesn’t matter. It doesn’t matter what you call it. It is love. It doesn’t even matter when someone denies you that definition, it is love because that’s what it was to you.

Love is not a word I like. It is so unoriginal, easy and overused. It is also so little and yet it can do so much. Catherine Lacey is a brilliant and brave writer. She is absolute magic. She isn’t afraid of the word love, of describing what it is, what it feels like, what it does, of defining it as variously as possible. And she’s not afraid to make you laugh at it. Its silliness. Or to take it up in all its seriousness. I’m so grateful, as a reader, and more so, as a human being in the world just trying to live. There are so many good lines here. One that stood out to me was: “People could call love whatever they wanted, but it was really just a long manipulation, a changing, a willingness to be changed.” When I read that line, I looked up and saw my face in the window. And something about it had changed. I could see beyond that. I was there. I hadn’t read anything that could do that to me in a long time.

—Souvankham Thammavongsa, whose poem “Twins” appeared in our Spring issue.

The First Blast to Awaken Women

Degenerate, Rachel McCrum (Freight,

2017)

I bought a copy of Rachel McCrum’s debut collection The First Blast to Awaken Women Degenerate immediately after seeing her perform at an Ottawa open mic. Putting that book down, after reading it all in one sitting, was like exiting a boat; I suddenly had sea legs to unlearn. With an intuitive sense of crescendo and an insane knack for last lines, McCrum has built a collection that could be considered a voyage made of puzzles, or maybe a puzzle made of voyages. McCrum performed her poems excellently, but I think I liked the poems most when I read them alone at home. That way I could react in “the rented privacy / of a lurching room.”

Less, Andrew Sean Greer (Little, Brown and Company, 2017)

I don’t often react physically to the books I read. A funny line of prose, for instance, will only make me breathe out of my nose a little sharply. But now that I think about it, one particular chapter of the novel Less by Andrew Sean Greer hit me hard as a stand-up special while I was sitting alone at a café. The bloodhound asleep on the floor near my table shot awake; people chatting amongst themselves stopped and turned. Less follows a sort-of-successful novelist around the world as he distracts himself from his ex-boyfriend’s impending wedding. Every chapter is funny, but the sojourn to Germany especially. It’s a good read for those who crave that warm, fuzzy feeling that literature can only create when it doesn’t care how cheesy it’s being.

—Ben Ladouceur, whose short story “This Must Be the Nature of Things” appeared in our Fall issue.

Hothouse, Karyna McGlynn (Sarabande

Books, 2017)

There’s a texture to Karyna McGlynn’s poetry, something gummy or abrasive. It gets stuck in your mouth. Hothouse is sectioned off to mimic the structure of a building—bedroom, library, parlour, wet bar, bath, basement—and the poems inside invite readers to visit a surprisingly intimate space. “So you want to know where I live?” she asks in the titular opening work. “Come here, love. We’ll circle the walls / with my big rococo key & look for a way in.”

Her writing is surprising and accessible and often really funny, approaching identity and connection with droll observational wit. “When he touched me / down there, he expected combustion. / But I was not his dad’s red Bronco—idle, / looping I smell sex and candy here” she writes in “Broken Bottle of Vanilla Fields,” one of several poems that make use of the setting and vocabulary of teenage years. Many of her poems find the speaker slipping in and out of various identities: “Self-Portrait as Erotic Thriller,” “Self-Portrait as Aging Starlet.” These variations in identity are effective not because she shifts seamlessly from one to the other, but because she puts the seams right up on display. Throughout, she exposes something raw and realistic about the effort it takes to connect and to create.

—Maija Kappler, whose

Letter from Montreal “The Still Waters of the St. Lawrence” appeared in our Spring issue.

Baseball Life Advice, Stacey May Fowles (McClelland &

Stewart, 2017)

I never thought I’d weep my way through a baseball book, but Stacey May Fowles proved me wrong. A love letter, manifesto and sincere thank you, Baseball Life Advice is written in the kind of nuanced, open-armed way that lets everyone from old hands to newbies get enveloped in the highs and lows of The Show and all its beauties and intricacies.

Fowles’s sports writing is spellbinding, and there were parts where the hair on the back of my neck actually stood up: the Marlins’ emotional win in honour of their dead pitcher, the breathlessness of watching a potential no-no unfold, the Jays’ fateful bat-flip game. But this is also a book about love and life and pain and triumph, and how all of that ties back to the sport Fowles loves. Furthermore, it’s a poignant and pointed observation about gender: the chapters on being a woman who loves baseball and writes about baseball were especially powerful, reinforcing that the old boys’ club still thrives and there is much work to be done.

Maybe you’ll come for the baseball, stay for the exquisite observations on life, femaleness, and striving to find your happiness. Maybe you’ll come for everything but the sport, and end up staying for the lush baseball writing. Either way, you’ll find something to love here.

—Anna Maxymiw, whose piece “Occult Favourite” will appear in our Winter issue.

The Death and Life of Great American Cities, Jane Jacobs (Vintage, 1992)

Living in Vancouver right now, it’s easy to become morbidly cynical about the state of housing and gentrification and city life in general. There’s no housing, Chinatown is on the verge of being destroyed and the opioid crisis is showing no signs of slowing down as the municipal government continues to hand land over to developers. As 2017 marched on and the situation in Vancouver continued to deteriorate, I found myself turning again and again to Jane Jacobs’ The Death and Life of Great American Cities for comfort. I’ve been reading it slowly for years, and this year is the one that finally pushed me to finish it.

Jacobs’ tone is soothing, her tales of planning history and solutions to common city problems delivered in the same congenial, irreverent voice as her admonishments of the ignorant men who came before her and the problems they created. But more than comfort, this book gives me hope that things can be different. In clearly laid-out chapters, Jacobs describes the concrete factors cities need to become lively and safe. She outlines why guaranteed-rent buildings would succeed in providing housing for all and why income segregation and public housing projects continue to fail. She knows that communities are capable of improving their own neighbourhoods—on their own terms and for their own benefit, no less—if municipal governments would do little more than quit sabotaging them and stay out of the way.

Her faith in the strength and beauty inherent to cities is inspiring, and her focus on strong communities is both practical and prefigurative. For me, the takeaway is clear: not only are Vancouver’s problems not inevitable, they’re not irreparable, and Jacobs had been telling us for decades how to address them. Fifty-six years after it was first published, in a city whose demise more often than not feels imminent, this book is more relevant than ever and a much-needed balm for anyone fighting for a place they love.

—Erin Flegg, whose piece

“New Space, Old Politics” appeared in our Fall issue.

The Far Away Brothers, Lauren Markham (Crown, 2017)

Ernesto and Raúl Flores, identical twins from El Salvador, seem like stereotypical teenagers. Their life involves plenty of texting; they scroll jealously through Facebook posts; they have on-again-off-again girlfriends. But they are also undocumented immigrants, smuggled—in the back of vans and through deserts—by “coyotes” who charge so much that their family back home, in the gang-ridden region where the twins grew up, worry they will lose everything. For the twins, it’s all worth it. In El Norte, they imagine the glimmering possibility of a better life. In El Norte, they hope, gangs don’t hijack busses, the bodies of the murdered aren’t dumped in unmarked graves, and everyone can afford a new pair of Nikes.

If ever anyone has wondered why young people might face such grave risks as to leave everything behind to live illegally in another country, The Far Away Brothers provides clear answers. “We measure water in gallons or liters, distance in miles or kilometers, height in feet or meters,” Markham writes. “Murders are measured in units of 100,000. In 2011, when the twins were fifteen—prime gang recruiting age—the murder rate was 71 out of 100,000 people.” By Markham’s calculation, that’s twelve murders each and every day. The genius of Lauren Markham’s The Far Away Brothers is that it takes on the enormous issue—and more topical than she could have ever predicted—of immigration in the US, while weaving in the fraught teenage drama of twins who have left behind everything they know for a new life.

Markham visited El Salvador several times for this book and undertook the painstaking process of asking two teenagers, and their families and friends, to recount time and time again the details of their childhood, their journey, and their lives in the US. The result is a beautifully written piece of journalistic-yet-narrative literature, with an omnipresent, and heavy, dose of reality. I had the pleasure of fact-checking The Far Away Brothers, and it was one of the most difficult pieces I’d ever worked on. I’d start out with the manuscript, a red pencil, and my laptop at the ready. Later, I’d find myself three chapters in: my pencil cast aside and totally engrossed.

—Sharon J. Riley, whose

feature “Tree’s a Crowd” appeared in our Fall issue.

Transit, Rachel Cusk (HarperCollins,

2017)

I keep trying to describe Rachel Cusk’s Transit to people, and I keep failing miserably, which might be part of what makes it such an incredible accomplishment. Like its predecessor, 2014’s captivating Outline, Transit tracks a largely anonymous narrator through a series of unconnected encounters: the Albanian builder renovating her flat, an online astrologer who contacts her with “important news” regarding her future, a flustered, lonely fashion designer. These characters regale our narrator with stories, memories and private anxieties, their winding monologues glimmering with uncertainty and hope, self-delusion and brutal honesty. All the while, their subject, our protagonist, remains silent, inscrutable: a passive observer past which the novel flows.

Transit continues the bold narrative experiment begun in Outline, jettisoning the expected rules of how a novel should behave in favor of something more restless, unusual, ambiguous—a meditation on intimacy and identity filtered through a distant, fragmented lens. But don’t get the wrong idea: Transit consistently delivers passages of such penetrating clarity and emotional insight that they actually took the wind out of me. What does it mean to be an individual? Do we develop as people because of the actions of others, or in spite of them? And do others free us from loneliness, or simply reveal how alone we are? Cusk’s mesmerizing anti-narrative may not leave us with any of the answers. But it provides something just as valuable: a wholly original way to ask the questions.

—Will Preston, whose piece

“Tall Tales from the Underground” appeared in our Spring issue.

The Sarah Book, Scott McClanahan (Tyrant Books, 2017)

Here’s how Scott McClanahan’s The Sarah Book begins: “There is only one thing I know about life. If you live long enough you start losing things.” In the novel’s 240 pages, the narrator—who is named Scott McClanahan—jumps nonlinearly between memories of his failed marriage, with tragic and comedic moments woven indiscriminately. Scott and Sarah meet in a candy store as teenagers, they fight in parenting classes and sign divorce papers, she gorges on breakfast food on their first date and becomes frantic for a washroom, he yells “I’m going to kill the computer” (and does so with a sledge hammer) during their worst fight. At one point, it’s the middle of winter and Scott is freshly divorced and he sees a box of kittens outside his apartment in the snow. He feeds the kittens hot dogs and ground beef for a few days and then accidentally kills one of them with his car on his way to his teaching job. After that, he deliberately runs over the “kitten lump” every day, figuring eventually it will be completely gone. The novel functions in the opposite way. By repetitively working through the most minute and unsavoury moments of his life with Sarah, he creates a sense that, carefully arranged, the things we lose can be made eternal.

—Thomas

Molander, whose book reviews appear in our Fall and Winter

issues.

The Break, Katherena Vermette (House of Anansi, 2016)

I ordered my copy of The Break by Katherena Vermette after taking a course called “Reconciliation through Education” at UBC, free to anyone interested in learning about the stain of government treatment of Indigenous peoples. Tasked with teaching the “Creative Writing Life” course at Trent University, I craved an inclusive and diverse reading list that would highlight an Indigenous experience in Canada while also showcasing the power of cultural storytelling. Katherena and I took the same fiction class for our MFAs in Creative Writing at UBC where I had the pleasure to workshop her submissions several times a year. Her writing was magic, even then.

I finished The Break in a day. Cliché, but I couldn't put it down, my copy full of turned-down pages and tacky coffee splotches from a rainy October day spent entirely indoors. And then once I turned the final page, I cried. I journalled. I scribbled lesson plans. I re-read my favourite passages and highlighted them with streaks of waxy green pencil crayon. The pages are almost entirely coloured like a Christmas tree.

The Break made me uncomfortable—not normally a feeling we cherish when reading, but the themes made me shift in my chair as I addressed my preconceptions and prejudices, holding them up to scrutiny, while also taking a harsh look at our historical and current treatment of Canada's Indigenous people. Joan Didion says she writes to better understand “what I'm thinking, what I'm looking at, what I see and what it means,” and I can't help but feel that's also why we read. I see what Vermette is showing the reader, and finally, after turning the final page, I know what it means.

—Kelly S. Thompson, whose piece “Battle Fatigue” will appear in our Winter issue.