The Great Comeback

Twenty years ago, Dave Bidini’s musical career was in a funk. Then a chance encounter with a jazz legend turned it all around.

MY BAND, THE RHEOSTATICS, broke up in 1988. We had found some success on college radio, and, after plotting our almost-certain ascension to Canadian rock and roll supremacy, I was devastated. What was I going to do? Forming another band seemed a betrayal, and going solo sounded as appealing as returning to the Etobicoke shoe factory where I’d worked before turning to a life on the road. The labour was mindless and the acrid taste of diesel and dust stuck to the back of my throat. Workers called it “the hellhole,” and on most days it was. (Once, the plant’s eldest employee, a gaunt, grey-whiskered man, was humiliated in the lunchroom by the plant manager for his longstanding habit of drinking two Labatts Blue during breaks.) Unless someone rescued me, I was going back there.

Then, a stroke of luck: the CBC called. I’m as troubled as anyone with the broadcasting trends that have afflicted our national radio and television: designer shoe exposés; knee-jerk reality programming; and the complete absence of documentaries on the main channel. But I am forever indebted to the CBC for saving my ass when I had fuck all else to do.

A few years prior, in 1985, I’d taken the train to Montreal to appear on Brave New Waves, one of the CBC’s great, uncategorizable music programs (David Wisdom’s Nightlines was the other). At the time, Brave New Waves was hosted by a woman named Augusta LaPaix. Her smart, sly and womanly tenor was the soundtrack to a show that fed listeners with music that couldn’t be heard elsewhere. I’d written her a letter in support of bands I’d seen perform in Toronto—Dave Howard Singers, Disband, Blibber and the Rat Crushers—and offered to come on the radio to talk about them. She wrote back, extending an invitation. Walking into her studio in the broadcast centre in Montreal for our interview, she took a long drag from her cigarette and said, “You look like a young Leonard Nimoy.” Then a red broadcast light came on. I was talking to Canada for the first time.

In 1988, when the show’s producers started looking for a summer replacement host for LaPaix’s successor, Brent Bambury, they gave me a call. I went back to Montreal for an audition with the producer, Heather Wallace, and even though I was sick with nerves, I got the gig. On the train ride home, I sat next to an old woman from New Brunswick, who asked what I’d been doing in Montreal. When I told her, she said, “Young man. You’ll tell the world. You’ll tell it everything you know and the world will be a better place.”

I was barely adequate that first month on the job. David Ryan, the show’s other producer, tried keeping my spirits up while Heather regularly took me aside to give me the bad news. The radio show was hard work for me, but even harder for her. Eventually, I stopped shaking every time I spoke, and grew into the feel of the program: careful and thoughtful, yet lively when it had to be. I started getting letters from listeners—just as Brent had. One of them was from an inmate who said that he listened to me after lockdown, where, he wrote, “the lights go out, the radio comes on, and we take something for our heads.” Another letter came from GG Allin, the notorious deathpunk masochist singer-songwriter. He said that he liked what I was doing and sent press clippings of himself in OUI and Screw magazine, the only publications who would write about him.

The producers brought me an endless procession of musicians whom I was required to interview. I talked golf with Zimbabwean legend Thomas Mapfumo, archealogy with the Pixies and Puerto Rican music with Yomo Toro, who, every year, leads the Puerto Rican parade through the Bronx. I interviewed the Ramones, whom I’d met before, filmmaker Gus Van Sant, and UK band the Happy Mondays. Before my interview with them, Heather asked if I was okay with English accents. I told her that I was, but the band’s Manchester patois was so thick that I’d simply ask a question, then nod my head as they rolled joint after joint: enormous, cone-shaped constructs which they smoked, delighted, in Studio 205.

Dave Bookman came to visit me one weekend. Dave and I had done a sports radio program at CIUT, a campus station in Toronto. He’s now the most popular rock and roll announcer in Toronto, but even as a college broadcaster you could tell that he had the stuff to move to a wider stage. After one of my CBC shows—we taped them at 5 PM and they aired at 11:05 PM—we drove out to an old amusement park by the water, where we sat listening to the broadcast. After listening to the first few songs of the program, Dave asked, “How does it feel playing other people’s music, but not playing music yourself?”

I told him that it felt great. Which it had, until I started to think of it in these terms. I also realized what Dave was implying: that I’d never be as good on the radio as I’d been on stage, playing in a band. I’d traded in my vocation—something I’d wanted to do my entire life—for what, in the end, was starting to look something like a career. Once I grasped this, the rest of my summer at Brave New Waves was affected by the push and pull of melancholy. I was thrilled by the chance to meet so many wild and interesting musicians, but I was heartbroken that I might never end up becoming one of these people myself.

Back in Toronto, the other members of the Rheos had moved on. They’d found jobs, returned to school, joined other bands. Only after we reformed a year later did I learn that everyone else had suffered through the same sort of conflict, wondering whether we shouldn’t have just tried to get along instead of tearing apart something that had meant so much to us.

One evening, I received a phone call from our bass player, asking if he thought the rest of the band would be into reuniting for one show in support of a charity event his friend was organizing. I told him that, because I was working in Montreal, it might be tough. Of course, I was full of shit. I wanted to get back to playing together more than anything else in the world.

Still, there were things about Montreal in the summertime that I loved: going to old Club Soda at the foot of the mountain; bagels dipped in tzatziki; coffee at Café Cine Lumière; the Expos. My girlfriend had also moved to the city, and we spent our evenings walking the streets, enthralled by their electric pulse. We were young and in love and living one of the world’s great cities. Held to the CBC’s bosom, it wasn’t hard to see my future laid out before me.

One afternoon, Heather called me into her office to tell me that Brave New Waves had been granted the only interview with the Montreal Jazz Festival’s honoured guest, Charlie Haden, the legendary jazz bassist who was recovening his groundbreaking Liberation Music Orchestra for the first time in twenty years. The Liberation Music Orchestra album is regarded as one of the first great Afro-Cuban-American efforts, and Haden was one of the masters of the genre. Heather said that it would easily be the most important and challenging interview of my career. A man of few words, Haden would be hard nut to crack.

On the day of our chat, the studio was heavy with security, as if the prime minister himself had been booked. A bag of nerves, Heather produced a bottle of wine and a tray of hors d’oeuvres for the event. I had prepared by reading whatever I could about Haden’s life and career. I learned about how he’d come to New York City as a member of Ornette Coleman’s free jazz combo, and how, when he looked down at the bar before his first gig in the city, both Charlie Mingus and Ray Brown had arrived to watch him play. According to one story, Haden had an appreciation for bluegrass dating back to his childhood, so I brought my Delmore Brothers album to the studio. When he settled in across from me, I drew the record from my bag, and his eyes brightened. He spoke excitedly about the little-known Delmore Brothers’ influence on bluegrass and country and I asked him if he wouldn’t mind signing the record. He did, and then Heather turned on the red light.

I asked my first question, and to everyone’s relief, he spoke for ten minutes. The rest of the interview went accordingly, and, by the end, I was thrilled that I’d survived, perhaps even thrived, in the moment. Heather’s coronation followed. “You’re the kind of broadcaster,” she said, “who can obviously handle whatever’s put in front of them. I’m so proud of you.” Afterwards, I began thinking that maybe a career in radio wasn’t so bad. Maybe there was a sense of achievement to be had, after all, and maybe it would be my fate to engage musicians and draw them out of themselves, rather than play music myself.

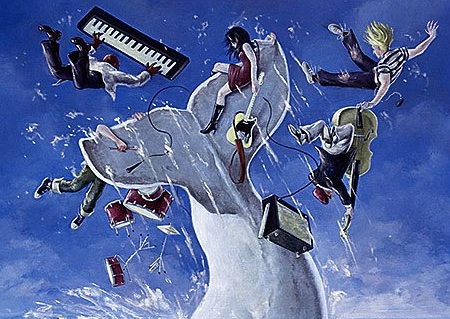

That night, my girlfriend and I hit the town. We went for dinner, got drunk and made our way back to her apartment on Clark Street, just off of St. Laurent. Walking home, a limousine pulled up beside us, and the doors swung open. Charlie Haden was the first to step out. He’d just finished his show at Place Des Arts, and the rest of the band followed him from the vehicle: Cubans and Americans, their arms slung around each other, laughing and holding drinks, moving in the kind of post-gig ecstasy I remembered from my days with the Rheos. My eyes met Charlie’s and he extended his hand. Our palms touched and I felt a great electric shock rise through my fingertips, along my arms and into my shoulders. Charlie felt the same thing, and we both skidded back on the pavement.

“Whoaaa!” he said.

“Whoaaa!” I echoed, in return.

We left each other on the sidewalk. I turned and headed home, knowing exactly what I had to do.

See rest of Issue 33, Fall 2009.

Read interview with David Bidini.

Read Bidini's "Travels in Narnia" (Spring 2009.)

Read Bidini's "Mongolian Invasions" (Summer 2009.)