Members Only

It is an important rite of passage: the breakup of the band you once loved. Dave Bidini recalls the friendship that sank with New Wave.

FOR A MUSIC FAN, no memory is more enduring than an encounter with a famous musician.

You’ll be sitting in a bar or riding in a cab or stuck on a bus when a song will come over the radio or karaoke machine or piped-in CD shuffler, and you’ll recount the time you played Space Invaders with Ian McCullough or peed besides James Moody or met Jerry Lee Lewis in Cannes or talked to Louie Bellson in the waiting lounge of your LA publisher, where you watched him play paradiddles on his snare drum cufflinks, which had little gold sticks hanging off them. You’ll describe the shape and colour of Stan Rogers’ nose and the noises that David Bowie made as he slumbered in bed beside you. Or the time Neil Peart asked if you wanted to go out behind the coach house and get high and how the first thing Neil Young wanted to know was whether or not you liked the Doors.

Sometime in the late seventies, when I was fifteen, I met a British New Wave group called the Members. They were a four-piece white reggae pop-punk band from London. My friend B and I discovered them opening for Joe Jackson at the Seneca Fieldhouse in Toronto. They had in spades the one thing an opening band is supposed to possess: the moxie to try and upstage the headlining band—which, on this night, they did, if barely. Because I’d never seen a real punk band before—or at least a band that had been born from the loins of that movement—I was thrilled by their relentless energy, working-class songs and scrapyard faces.

Within a few songs of their set, B and I were their crowd champions, dancing and cheering wildly. Following one song, the guitarist—Nigel Bennett, a flat-nosed, gum-chewing, afro-haired, leather-jacketed goon—came to the lip of the stage, looked down at us and laughed. It was the first personal connection I’d made with anyone on stage, and while Nigel Bennett will never be mentioned in the same breath as Jimi Hendrix or Pete Townshend or Richard Thompson, to us he was all of those players and more. He was ours.

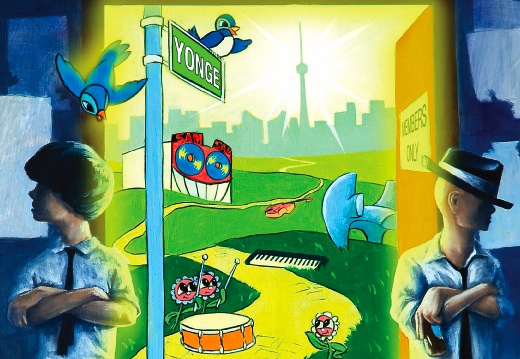

B and I were utterly devoted to the Members. We collected all of their 45s—most of them were imports—as well as their debut album, At the Chelsea Nightclub. When they returned to play at the Edge, one of North America’s first and best new music clubs, we arrived early in the day and waited for them. After they’d loaded in and finished sound check, I asked if they’d sit for a college radio interview, and they said they would. They drank beer and listened patiently to my junior reporter’s questions, and when the interview was over, they asked if we knew where Yonge Street was. We said that it was just “over there,” and they said, “Well, show us, lads!” So B and I strolled shoulder-to-shoulder through the streets alongside our heroes, feeling cooler than we ever thought possible.

B and I liked other bands, too. I’d go over to his house on Saturday morning and, pockets stuffed with our parents’ money, we’d catch the subway downtown to shop for records, carrying an armful of $5.99 vinyl home after a long day shredding through the racks. We made tapes in his room and jammed to Fear of Music by Talking Heads and Drums and Wires by XTC.

But it was the Members we loved. The day their second album, The Choice is Yours, came out, we were the first people in Canada to buy it, waiting outside The Record Peddler before it opened. I remember the owner, the late Ben Hoffman, crouching over a cardboard box filled with British imports, and B and I standing over him, our hands pressed eagerly together.

“What the fuck do you guys want?” he asked.

“Is the new Members album in there?” we asked.

“The Members? Yeah, I think so.”

“Cool. We heard it was coming out today.”

“How?”

“It said so in the NME.”

“Did you hear what else?” he asked.

“No, what else?”

“The album comes with a tie. A Members tie.”

“No fucking way!”

“Way,” he said, sliding the album out and hiding it from view.

The tie was long and skinny with the Members’ name printed length-wise. Bands who have fan clubs and offer discounts on T-shirts are one thing, but bands who give their fans free ties represent an altogether elevated form of symbiosis. We wore the ties to school the next day.

Growing up, B and I were as close as two friends could get. We lived in each other’s back pocket. We smoked pot and got drunk together, fought other kids together, and, when we started to go out with girls, we did this together, too. The girls were also best friends, so it worked out well. When my parents went out to dinner, B and I would take the girls back to my room, where we rolled around on the scratchy carpet with our clothes off, fumbling in the dark around spilled albums and old Hit Paraders with Debbie Harry on the cover.

Then, hours later, we would drink warm beer in the driveway, leaning on the back fender of B’s mom’s car. It was late summer and Grade 12 was coming next. In a few years, we’d be living downtown, playing in bands, taking streetcars from rehearsal space to bar to shitty apartment. But for now, the suburbs hummed and the future promised nothing.

A few years later, the Members returned to Toronto to support their third album, Uprhythm, Downbeat. It was a tough pill to swallow: the album was nowhere near as fun or energetic or young-sounding as the others. B and I dealt with this like any aficionado would: we blamed bad production, an overbearing record company and a ragged touring schedule that prohibited the band from properly worrying over their material.

But when they showed up to play Larry’s Hideaway in Toronto, we saw that the problem ran deep. There was no eager, midday propulsion in search of the city’s sites—the band opted for their hotel rooms to sleep or phone home. There was no joyful jumping around and laughing at the crowd—they more or less stood there, running through their mostly new songs. Also gone was their hardscrabble look, their bedheads replaced by teased and hennaed hair, their crummy jackets traded in for clothes that someone else had chosen for them.

After the gig, we visited the band’s dressing room, which we’d always done. In the corner sat two young fans the same age as us, fiddling with a tape deck used to record the show. After getting it started, the Members’ singer, Nicky Tesco—on his chair, sprawled in a bathrobe—shouted: “Turn that fucking shit off!” We fled, and never saw the band again.

Things went south between B and me. We grew quieter, stopped talking to each other. Trips downtown were marked by long spells of silence, and, after a while, we drifted apart. We made new friends, developed different interests, but still hung out, figuring we owed it to our past relationship.

One night, at a friend’s party, we started arguing and things got personal. Soon, we were screaming at each other. At the end of it, B turned away and said, “I can’t even fucking talk to you anymore.” It was last time we’d say anything honest to each other. From then on, it was the occasional pleasantry or stupid joke. Without our favourite band to unite us, we became strangers to each other. When the Members broke up, our friendship died. And with it went my teenagehood and whatever suburban scent I’d carried with me.

A few weeks ago, I rode the bus past the park where B and I would get high before heading downtown. Staring out on the scene—unmoving swing set and baseball diamond with mud hardened along its edges—I saw the two of us, wearing parkas and laughing, smoke everywhere.

Pick up Issue 35 of Maisonneuve for Dave Bidini's newest column "Shoot it Harder, Lads!"

Related on maisonneuve.org:

—Interview with Dave Bidini

—Travels in Narnia

—Mongolian Invasions

—The Great Comeback

Follow Maisonneuve on Twitter — Join Maisonneuve on Facebook