The Incredible True Story of Mr. Markarian

One man's battle against CIBC exposes the billion-dollar scams behind our country’s “stable” financial sector.

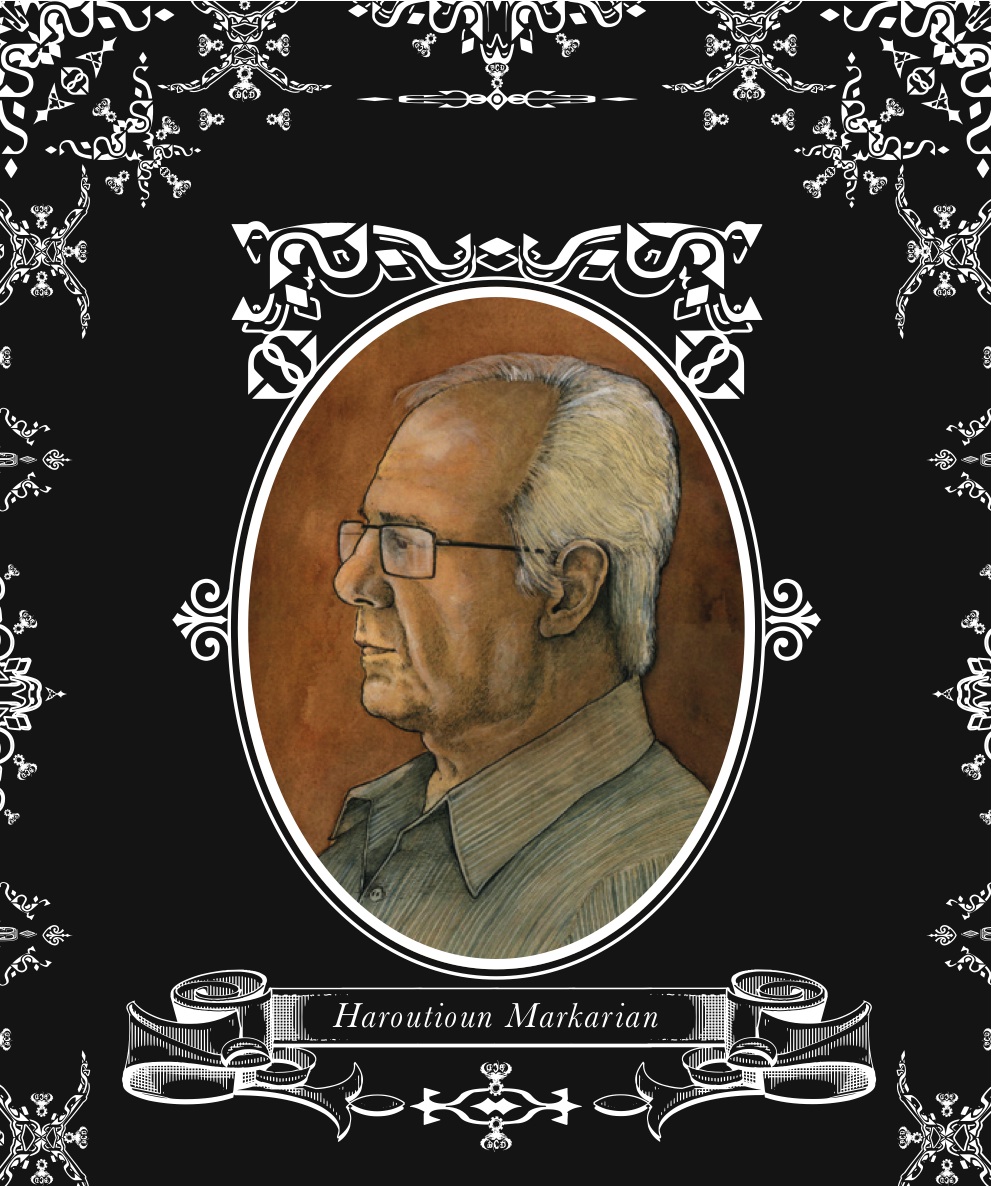

Illustration by Pat Hamou.

SERGE LÉTOURNEAU was getting impatient. It was February 14, 2005, and he was in a courtroom at Montreal’s Palais de Justice, grilling Thomas Monahan over his decision to axe an employee four years earlier. Monahan was the forty-eight-year-old head of CIBC Wood Gundy, and Létourneau was representing retired businessman Haroutioun Markarian, who was suing the brokerage house in order to retrieve $1.5 million it took from him under very questionable circumstances.

Why had the bank made off with Markarian’s money? Throughout the nineties, Markarian’s broker was a man named Harry Migirdic, who had worked out of CIBC Wood Gundy’s offices in Montreal. In 2001, Migirdic broke down and confessed to his bosses that he’d been losing his clients’ money with reckless abandon. To hide these losses, he tricked wealthy clients like Markarian into signing guarantees that made them responsible for the deficits.

In spite of Migirdic’s admission that Markarian had “no clue” he was signing such guarantees, CIBC Wood Gundy enforced the controversial agreements and emptied Markarian’s bank account—leaving all of $2.54. Monahan then fired Migirdic. Still, he insisted the guarantees were legitimate, but by terminating Migirdic, CIBC Wood Gundy seemed to concede otherwise.

“Did you consider that [Migirdic] obtained a fraudulent signature of Mr. Markarian on the guarantees? Was it one of the facts that justified his dismissal?” Létourneau asked Monahan.

Monahan rambled, realizing he was stuck in a contradiction: why fire Migirdic unless he’d committed fraud? “But we didn’t know that it had been fraudulent,” Monahan replied. “We knew that that was what he said…and we knew that we had reliable guarantees that had been duly signed by a sophisticated businessman.”

“So the acknowledgement by Mr. Migirdic of fraudulent guarantees was sufficient to justify his dismissal?”

“Not sufficient on its own.”

“But was part of the reason that explained his dismissal…”

“Part of the reason.”

“But not sufficient to void the guarantees.”

“That’s correct.”

“It’s a win-win situation for you, right?” Létourneau asked.

“I don’t see it that way,” Monahan answered.

VERY FEW PEOPLE KNOW about the 2005 trial known as Markarian vs. CIBC World Markets Inc., much less the judgment that emerged a year later. Toronto media ignored the proceedings, and only the Montreal Gazette sent a reporter. Yet the case achieved something unprecedented: it exposed the staggeringly corrupt inner workings of Canada’s trillion-dollar banking and brokerage industry.

Canada has a long record of investment fraud, stretching from Bre-X, Philip Services, YBM Magnex, Hollinger, and Nortel to Ponzi schemers like Earl Jones, Weizhen Tang and Tzvi Erez. A 2007 survey for the Canadian Securities Administrators estimated that more than one million Canadians have lost money in some sort of financial scam. Diane Urquhart, who spent twenty years as an analyst and head of research at some of Bay Street’s biggest brokerage houses, claims that investment fraud costs Canadian investors a combined $20 billion every year. “It’s a coast-to-coast problem,” she insists. “The consequences are now in the billions of dollars.”

The same culture of impunity lies behind the 2008 crash. It’s well-known that Wall Street’s credit crisis triggered the collapse of storied firms like Lehman Brothers and Merrill Lynch, the bankruptcy of countries like Iceland, and the decimation of savings, pension funds and job markets worldwide. But a story as yet untold is the corruption of Canada’s banking and brokerage industry—a sector lauded by our politicians, business leaders and pundits for its prudence and stability. The Financial Times calls our banks “the envy of the world,” and New York Times columnist Paul Krugman praises Canada’s “boring” aversion to risk. Meanwhile, Ontario Securities Commission (OSC) chairman David Wilson says Canada’s banking sector “has managed to get through this crisis just about better than anyone else.”

Not quite. While no Canadian bank or brokerage house has gone bust, and our suburbs never fell prey to subprime mortgages, it’s pure fantasy to claim the country is free of the licentiousness that brought the global financial industry to its knees. “We have had a credit crisis on Wall Street,” explains Urquhart. “That same credit crisis has already happened in Canada. It just doesn’t have the publicity of the American crisis. So it’s not correct to say Canada is better regulated, that we are a better financial system. Quite to the contrary. We have had significant losses borne by the Canadian population.”

How does this credit crisis manifest in Canada? Five big banks dominate our financial industry, and they, in turn, own large brokerage houses. On one hand, these banks are stable: government regulation ensures they don’t become insolvent by, say, overleveraging. On the other hand, they are virtually unregulated when it comes to losing, squandering or skimming investors’ money by selling rotten financial products. For example, $32 billion of Canadian companies’ and small investors’ money wrapped up in asset-backed commercial paper—a shady investment vehicle sold as Triple A-rated, and one of the roots of the financial crash—froze up in 2007. Suddenly, investors couldn’t access their own money. Still, despite misleading investors about the safety of the paper, the financial industry finagled a public deal whereby it paid just a fraction of what was lost—about $300 million—and is protected from lawsuits. Investors will get some of their money back, but only after waiting until 2017.

Banks and brokers are rarely held to account because, unlike most other Western countries, Canada has no national securities regulator for capital markets. Instead, we have a hodgepodge collection of thirteen weak-willed securities commissions, all of which are run by bankers or corporate lawyers who work for the financial industry. For example, before he took over as the $705,000-a-year chair of the OSC, David Wilson was vice-chairman of Scotiabank and CEO of Scotia Capital, the bank’s brokerage house. It’s not hard to see why Canada is a veritable prosecution-free zone for financial fraud.

“Enforcement in Canada is pathetic,” says Utpal Bhattacharya, an associate professor of finance at the Kelley School of Business at Indiana University, and the author of a 2006 report that examined Canada’s record of punishing stock market fraud. “Canada is so advanced in many things, but when it comes to prosecuting white-collar crimes, they just don’t do it.”

Indeed, when Bhattacharya compared the OSC and the US Securities and Exchange Commission’s (SEC) records between 1997 and 2005, he found that, when scaled for stock market size, the SEC prosecutes ten times more securities law violations per firm, and twenty times more insider trading violations than the OSC. Moreover, the SEC levies fines that are seventeen times larger per insider trading case. Bhattacharya says feeble enforcement costs Canada tens of thousands of jobs because foreign companies are leery of investing here.

Which brings us to the Markarian case. While the case predates the credit crisis, it’s a prime example of why Canada is such a haven for mischief, and why the banks are rarely brought to task for their actions. The Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce (CIBC)—Canada’s fifth-largest bank, with annual revenues of $9.9 billion—owns CIBC Wood Gundy. The way CIBC lurches from one catastrophe to the next, plagued by lawsuits while sucking back huge losses, one would think it a rogue bank. For example, due to its exposure to US subprime mortgages in 2008, CIBC had to write off losses estimated to be as high as $11 billion US—significantly more than any other Canadian bank. So much so that, in many reports, CIBC’s subprime losses are stated separately, while the other four banks’ are totalled together.

Back in 2003, the SEC fined CIBC $80 million US for its role in the manipulation of Enron financial statements, and sued the bank and three of its executives for “having helped Enron to mislead its investors through a series of complex structured finance transactions over a period of several years preceding Enron’s bankruptcy.” CIBC then had to cough up $2.4 billion US to settle an Enron-related class action lawsuit.

If these are the owners of CIBC Wood Gundy, is it any surprise that, according to the financial newspaper Investment Executive, brokers and financial advisers have described the culture of the brokerage house as highly toxic, with a “‘cover your ass’ mentality and stifling bureaucracy”? High turnover, cronyism, low morale, outdated technology and lack of training are among the many problems cited by former advisors. And as the Markarian case illustrates, Wood Gundy seems to scarcely care what its employees actually do with clients’ money.

IT’S NOT CLEAR if Harry Migirdic was always a fraudulent broker or simply became one over time. A portly, grey-bearded man with deep-set eyes and slicked-back hair, he initially worked at Merrill Lynch Canada until CIBC Wood Gundy absorbed the brokerage house in 1990. Merrill Lynch had promoted Migirdic to vice-president—a largely meaningless title often bestowed on brokers who bring in a lot of business. Migirdic kept this honourific at Wood Gundy, although Monahan admitted the tactic was “a marketing tool” to impress clients. By 2000, CIBC Wood Gundy had nearly two hundred of these “vice-presidents.”

After his move to Wood Gundy, Migirdic spun out of control, making disastrous investments with his clients’ money. One of his first victims was Rita Luthi, a Quebec businesswoman who entrusted $150,000 to him. By early 1993, only $18,000 remained, a fact Migirdic hid from Luthi. This became a problem when she sought to withdraw $60,000—money no longer there.

In order to cover up such losses and keep the money flowing, Migirdic created a ruse. In 1986, he had met Montreal businessman Haroutioun Markarian. A quintessential up-by-the-bootstraps success story, Markarian arrived in Montreal from Egypt in 1962 with $300 in his pocket and co-founded his own mechanical company. He sold the business and retired in 1993 with a nest egg of $4.5 million.

Migirdic went to Markarian and tricked him into signing a guarantee agreement. Such an agreement would allow Migirdic to drive Luthi’s account into the red, and CIBC Wood Gundy would look away, knowing that someone else was providing collateral. Once a year for the next seven years, Migirdic had Markarian sign updates on the guarantee, telling him it was merely one of the brokerage house’s bureaucratic necessities.

The method worked so well that, in 1994, Markarian was made to sign another, different guarantee—this time to cover heavy losses in an account Migirdic himself had opened under the name of an absent uncle. Migirdic used the ploy on others, too. In 1993, Kiganouchi Papazian, an elderly widow, unwittingly signed a guarantee to cover the debts of another of Migirdic’s clients. When Papazian’s son discovered the guarantee’s existence in 1998, Migirdic promised to rescind it. But he never tore up the document, and CIBC Wood Gundy seized $300,000 of Papazian’s money in 2001. She went to her grave heartbroken and penniless.

Migirdic’s appalling record doesn’t end there. He made 1,400 unauthorized discretionary transactions that cost a client $900,000 and lost a combined total of nearly $1.3 million from three different clients’ accounts. In fact, Migirdic committed just about every wrongdoing you can as a broker: unauthorized investments; unauthorized changes in client profiles; day trading; transactions with insufficient coverage; excessive speculation; illegal compensation of clients and conflicts of interest. At one point, the bank ordered him to pay back $250,000 because of losses incurred in debiting an account without authorization. And when he accepted a power of attorney document with a false signature, he was caught and fined $30,000.

All told, Migiridic is alleged to have lost $5 million of his clients’ money. Yet Migirdic was making a lot of money for himself and the bank. From 1991 to 2000, he billed over $11 million in commissions. Of that, the bank took $5.5 million. Migirdic appears to have pocketed the rest.

Why didn’t Wood Gundy’s compliance department notice Migirdic’s misbehaviour? In fact, it had spotted his alarming losses and use of guarantees, and even sent him notes of inquiry, but he always managed to talk his way out of it. At no point did a CIBC Wood Gundy compliance officer or one of Migirdic’s immediate supervisors call Markarian, Luthi or Migirdic’s uncle to ask about the bizarre happenings in their accounts.

Migirdic kept his job, likely thanks to the enormous commissions he was generating for the bank. As Toronto-based investor activist Robert Kyle—who spent twenty years on Bay Street as a derivatives trader—notes, Migirdic’s superiors would have “received a cut of everything. So if Migirdic is one of their top salespersons, they would be making a piece of that. Do they want to turn their own guy in if he’s making millions?”

IN THE END, Migirdic turned himself in. Stressed by his growing web of deceit, he contacted Wood Gundy head Thomas Monahan in February of 2001 and admitted there were “problems” with certain accounts. Monahan told Migirdic to write down the details of the fraud, and Migirdic indicated he deceived Markarian about the documents he was asked to sign. When Migirdic met with his superiors, he reiterated that Markarian never knew he was guaranteeing the debts of perfect strangers.

In March of 2001, CIBC Wood Gundy called Markarian and his wife into a meeting with Thomas Noonan—Migirdic’s boss—and a lawyer employed by the bank. Noonan showed the Markarians the signed guarantees, receiving confirmation it was Haroutioun’s signature. Noonan then told the Markarians that they now owed the bank $1.35 million. Their accounts were frozen and they could no longer carry out any transactions. Noonan and the lawyer never uttered a word to the elderly couple about Migirdic’s fraud or confession.

Markarian, sixty-eight years old at the time, went into shock. At the end of the meeting, he was unable to stand up, and had to be helped out of the room. He could not speak for fifteen minutes, then began asking his wife, “Is it a dream, Alice? Is it true?” Once home, a doctor was called to his bedside.

Markarian recovered and hired a lawyer, who immediately told the bank that the guarantees were signed under false pretenses and that it couldn’t seize the money. The bank ignored these overtures, refusing even to meet with the Markarians or their attorneys.

Monahan later testified that when he received Migirdic’s confession he didn’t know who or what to believe. He conferred with a passel of lawyers from CIBC and at the corporate law firm of Heenan Blaikie LLP. He also consulted with his superiors. Everyone agreed: it was okay to empty Markarian’s account.

This in spite of what both Migirdic and Markarian had told them, let alone the sheer implausibility of Markarian guaranteeing the losses of people he didn’t know. Moreover, after making this decision, the bank refused to investigate the matter further. “It is very typical of the industry,” says Kyle. “They are there to keep the money. They are there to make sure the money doesn’t leave.”

Markarian had no choice but to sue CIBC Wood Gundy to get his money back. In turn, the bank fought him every step of the way.

WHERE WERE THE REGULATORY BODIES and the police in this fray? Unsurprisingly, they mostly stood on the sidelines. The Investment Dealers Association of Canada (IDA)—now called the Investment Industry Regulatory Organization of Canada (IIROC)—is the self-regulating body of the brokerage world. Yet its membership and board consists of all the major banks and brokerage houses. When you complain to the IIROC, you’re complaining to the very people with whom you have a problem.

After CIBC Wood Gundy fired Migirdic in the spring of 2001, the IDA investigated his actions. The report that emerged three years later is both thorough and surreal. It painstakingly documents Migirdic’s crimes and frauds, from unauthorized trading and losing clients’ money to the Markarian case itself. But it doesn’t once mention the fact that CIBC Wood Gundy seized $1.5 million based on fraudulently obtained guarantees. Perhaps this omission is to be expected; CIBC Wood Gundy is a member of the IDA, and, amazingly, Monahan was sitting on the IDA’s board for part of this time. Today, the IIROC will not comment on why it deemed Migirdic guilty of defrauding Markarian but refused to examine CIBC Wood Gundy’s actions following the scam.

The IDA fined Migirdic $305,000, plus $55,000 in costs, and banned him for life from selling securities. (The CIBC also fined him $500,000.) But, because the IDA has no enforcement power, these fines are not legally binding. Migirdic has never handed over one cent. More significantly, he’s kept the millions he earned during his career at Wood Gundy.

After the IDA found that Markarian had indeed signed fraudulent guarantees, CIBC Wood Gundy offered him a mere $250,000. Létourneau asked Monahan on the stand, “Why didn’t you offer all the amount you took from them?”

“The basis of the decision was to try to sit down with Mr. Markarian and get into a discussion in order to settle,” Monahan answered.

“What’s new? What triggered that offer?”

“All of the facts were now on the table.”

“Which facts?” pressed Létourneau.

“The IDA investigation had been complete, the discoveries were complete.”

“What new information did you see in this [the IDA’s report] in April of 2004 that you don’t have before?”

“There was no additional new information that came forward,” Monahan admitted.

In November of 2004, the brokerage house finally said it was willing to pay back all of Markarian’s money. But CIBC Wood Gundy refused to cover his enormous legal bills—which were by then in excess of $300,000—or accept liability, or pay for interest that had accrued on the money. Markarian turned down the offer.

In the winter of 2005, during a break in the trial, Monahan met with a former CIBC Wood Gundy financial adviser named Allan Fenerdjian. Soon afterwards, Fenerdjian telephoned Markarian and suggested that he take the offer of $1.5 million (minus legal expenses) because, he said, Monahan had no intention of paying one dollar in punitive damages. Fenerdjian also told Markarian that Létourneau had a personal vendetta against CIBC and that his judgment in this case was clouded. This was an obvious attempt to coerce Markarian into changing his mind. It failed.

THE CASE WENT TO TRIAL in January of 2005. CIBC Wood Gundy insisted that Markarian was entirely responsible for his woes. He was a sophisticated businessman and must have known he was signing guarantees for Luthi and Migirdic’s uncle’s accounts.

Monahan spent two days on the stand. At one point Létourneau asked him why it was implausible for Migirdic to have fooled Markarian.

“You agree with me that you have, at Wood Gundy, many, many, many sophisticated employees,” the lawyer asked.

“Yes.”

“Very knowledgeable employees?”

“Yes they are.”

“Especially at the compliance department and everywhere?”

“Correct.”

“And you have been deceived…”

“Yes we have.”

“Completely.”

“Yes…”

“Why is it a big problem for Mr. Markarian to have been deceived since he is a very sophisticated businessman, and not for you?” asked Létourneau. “I don’t understand. Tell me.”

Monahan finally conceded that Markarian “was deceived by Mr. Migirdic.” Still, when Létourneau asked Monahan whether he felt justified in taking Markarian’s money, Monahan responded, “Yes.”

“You still maintain it today?”

“Yes.”

The trial went on for twenty-five days. And it would take more than a year, until the summer of 2006, for Judge Jean-Pierre Sénécal to issue a verdict. When he did, it was a blockbuster. Not only did Sénécal award Markarian his $1.5 million plus court costs and expenses, he also handed him another $1.5 million in punitive damages—the largest in Canadian history. Sénécal found Migirdic guilty of fraud, but also said CIBC Wood Gundy contributed to the fraud by failing to supervise him and “by giving meaningless, but prestigious titles to Migirdic.”

Sénécal accused the brokerage firm of treating the Markarians with “profound contempt.” He wrote: “It was as if the employer of a thief —the one responsible for fraud—made the victim responsible for his misfortune.”

Yet the lacerating decision had little effect. Migirdic kept his money and remains at large. Monahan ran CIBC Wood Gundy until the fall of 2009, when he left to become the CEO of CIBC Mellon, a financial services company that manages $1 billion in assets. The Quebec securities commission has not pursued Migirdic or CIBC Wood Gundy. The IIROC will only say the situation is under review. And best of all, Canada continues to enjoy the robust myth, here and abroad, of a boring, steady-as-she-goes, unimpeachable banking industry.

IT’S LONG BEEN RECOGNIZED that Canada needs an independent national securities regulator with its own policing unit—one that answers to Parliament and not the existing cabal of corporate lawyers and financial executives. Fines and sentences for breaking securities laws also need to be stiffened.

Other countries do a far better job of ensuring the fox is not the only one guarding the henhouse. Many have national securities regulators that are not as beholden to industry interests; even in the US, for example, the SEC and the states’ attorneys aggressively pursue cases of outright financial fraud and procure stiff prison sentences. Which is why Conrad Black, who committed his crimes mostly in Canada, got smacked with a six-and-a-half year prison term by a Chicago jury in 2007, while Jeffrey Skilling of Enron is serving twenty-four years, Bernie Ebbers of Worldcom received twenty-five and Dennis Kozlowski of Tyco is looking at a maximum of twenty-five—all paling in comparison, of course, to Bernie Madoff’s 150 years.

In the fall of 2007, Rob Kyle wrote to the RCMP and asked them, in light of Sénécal’s decision, to look into the Migirdic case. The RCMP declined, saying their “initial review of the material forwarded does not appear to support a criminal fraud allegation with respect to CIBC and its directors.” The RCMP suggested that prosecuting Migirdic was a matter for the local police. Yet Kyle found that the Montreal police were not interested in investigating the case either.

Today, Kyle remains appalled that Monahan kept his job. “The acorn never falls far from the oak tree,” he observes. “If this is a guy who all of his employees look up to, can you blame the brokers beneath him saying ‘Well, if this is what he can get away with, why can’t I?’”

Related on maisonneuve.org:

—Breaking and Entering

—Pure Laine Ponzi

—The Happiness Project

Follow Maisonneuve on Twitter — Join Maisonneuve on Facebook