Mean Streets

Sex tourism destroys the lives of millions of children every year, but activists are getting better at stopping Canadian predators in their tracks.

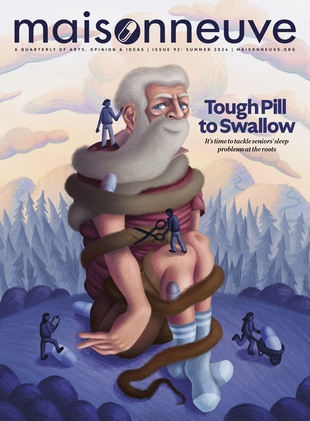

Painting by Antony Micallef.

WHEN THE SUN SETS on the neon-lit strip of Thailand’s famous beach resort, Pattaya’s vast bars become warehouses of women. Hundreds of Thai girls sit cross-legged on stools sipping drinks while sunburnt men stroke their legs. Others stand duty outside in heavy makeup, calling softly to customers: Sawatdee kaa. Welcome.

Crowds stream by: Western, Indian, Eastern European and Japanese men on vacation and on the prowl. Pattaya—its beaches, streets, shopping malls, restaurants and bars—is ground zero for Southeast Asia’s booming sex trade. In Asia alone, agencies estimate one million children work in the region’s $5 billion prostitution industry (with the age of initiation as young as four for boys and eleven for girls). The ready availability of Thai youth draws a half-million foreigners each year, Canadians among them. These tourists use child-sex hubs like Thailand as personal playgrounds, bases for pornography rings and safe havens to evade capture for sex crimes committed back home.

As midnight approaches, three schoolgirls slip into view, skipping along the strip in cotton skirts and flip-flops, the oldest no more than twelve, the youngest, waist high. The girls tug at hands and offer men single red roses with pleading looks. Tonight, they’re just peddling flowers. But someday, one of those men—perhaps a Canadian—will want much more.

IT’S A THOUGHT that keeps Rosalind Prober up at night. President of the Canadian anti-child-exploitation group Beyond Borders (which she co-founded in 1996), Prober has been fighting sex trafficking for almost two decades. Speaking across Canada and internationally, she’s seen and heard it all. But Thailand’s child-sex crisis still shocks. “Pattaya has become the sewer of Thailand,” she says. “There are no limits down there, no control.”

Boasting close to sixty thousand brothels, Thailand is a world centre for trafficking (a quarter of a million children are bought and sold in Thailand alone) and ranks fifth for child pornography. Enforcement is lax—hardly surprising when the industry is a major source of income—and even local police have been arrested for running brothels and pimping children. Sex tourism is extremely lucrative, feeds crime syndicates and crops up in new areas as well-known sites in Southeast Asia come under pressure. The scourge has spread to hotspots in India, Bangladesh, Nepal, Argentina, Peru, South Africa, Kenya and Guatemala.

Canadians who believe child-sex tourism happens “down there” and doesn’t affect them or their children are gravely mistaken, says Prober. Research shows some “situational” offenders prefer younger partners but would rarely have sex with children at home. Sex hubs like Pattaya embolden men to act on their desires because they think they can get away with it, turning some who may have only fantasized about abusing children into active offenders.

“It would be highly naive for any Canadian to believe that an individual who goes to a foreign country to take advantage of desperate trafficked children would come back and not abuse children here,” the Winnipeg activist says. “I think they come back more dangerous than they were in the first place.”

Indeed, critics charge that by ignoring the issue—in the belief that child-sex tourism is not Canada’s problem—we are effectively exporting our predators to poorer countries.

Take John Charles Wrenshall. He was convicted in 1997 of abusing eight choirboys in his hometown of Calgary. That didn’t stop him from searching for more victims in Thailand, where, presumably, he felt safer from capture. In December 2008, he was arrested and charged with running a child-sex brothel outside Bangkok, where, for $400 US, customers were allowed to videotape and photograph their encounters with boys aged six to nine. He is now behind bars in the US, awaiting trial on eighteen counts of child abuse.

In 2006, Saskatoon resident Robert Reddekopp was teaching English to elementary and high school students in Ayutthaya, north of Bangkok, when thousands of images of sexually abused children were found near his former home and traced to him. Arrested when he returned to Canada to renew his passport, he pled guilty to possession of child pornography and was sentenced to eighteen months’ house arrest. But Reddekopp told reporters that as soon as he served his sentence he’d return to Thailand. Authorities could do little to stop him.

Then there is Orville Frank Mader, a Kitchener, Ont., native who was wanted, in 2007, on a Thai warrant for abusing an eight-year-old boy in Pattaya while teaching English in the region. Police believed he’d abused others. Mader fled the country before he could be caught and was arrested upon arrival in Vancouver, only to be let out on bail here, free to re-offend.

“It’s embarrassing when you see how the scourge of child-sex tourism impacts on society,” Prober says, “how it impacts other countries, how it damages the reputation of our citizens, how it ruins families on both sides of the globe. And yet we let these offenders live among us, and we let them travel. We’re pretending child-sex tourism doesn’t exist.”

PROBER IS JUST ONE of many activists battling sex tourism. Back in Thailand, Montreal native Catherine Beaulieu is also working on the ground to keep offenders at bay.

A McGill-trained lawyer in her thirties, Beaulieu consults for an organization called ECPAT International (End Child Prostitution, Child Pornography and Trafficking of Children for Sexual Purposes). She monitors countries’ compliance with international child-rights laws and pushes for reform in places like Indonesia, Bulgaria and Uganda. Based in downtown Bangkok—just a stone’s throw from hotels where tourists bring prostitutes—ECPAT was created to coordinate worldwide efforts toward a shared goal: saving kids. But twenty years after the UN’s adoption of the Convention on the Rights of the Child, Beaulieu says, “there isn’t a single country that has put in place an adequate framework to protect children from sexual abuse and exploitation in compliance with international standards.”

This includes Canada. We have an extra-territorial law that allows Canadian authorities to prosecute nationals who commit crimes in other countries. But in cases of child-sex tourism, the law is poorly enforced. Between 1997 (when it was enacted) and 2007, 110 Canadians were charged with child abuse overseas. To date, only three have been convicted; a fourth will soon stand trial. “A law on the books,” Beaulieu laments, “can’t do much if it is not enforced.”

Not far from ECPAT, in a small office, Sudarat Sereewat, a delicate Thai woman in her late fifties, perches over a fax machine waiting for a report on Canadian offenders. A one-woman legal crusader, Sereewat has been chasing foreign pedophiles out of Thailand—and into jail—for fifteen years.

“These countries have to have responsibility of their own people,” says the founder of Fight Against Child Exploitation (FACE), an ECPAT partner. In the absence of official monitoring, FACE tracks foreign offenders arrested in Thailand.

It also assists child victims and encourages them to testify, helps police investigate cases, pressures the courts to act swiftly on trials, pays for lawyers and keeps records of what happens to offenders in their home countries. All told, Sereewat has tracked more than 160 court cases, some for over ten years, ensuring global accountability for child-sex offenders who know no borders.

“Otherwise, no one would know how it goes,” she explains. “The German guy left Thailand and then what? The UK man left Thailand and then what? I follow those cases. We have to make sure they [the courts] know they cannot just throw it out. We will not go away.”

Most offenders she’s dealt with hail from the US, UK, France and Germany. But she tracks Canadians too. Her list includes André Leduc, who in 2000 was charged with committing an indecent act with a thirteen-year-old-boy in Pattaya, and Jocelyn Leblanc, who in 2005 was caught abusing a five-year-old-boy in the southern resort town of Phuket. Leduc was jailed for a year, while Leblanc paid a 7,500 Baht fine—just $230 CDN.

“This is very bad,” Sereewat says, frowning, reviewing the outcome of the Leblanc case. Weak sentencing, inadequate police investigations, no national sex offender registry and lenient bail systems are constant frustrations in Thailand. “These foreigners, most of them jump bail,” she explains. “That’s why we expect the country of origin of those people to be able to prosecute them.”

Sereewat dreams of a day when foreign nations effectively share information about predators posing as tourists abroad. Until that happens, developing countries will continue to be left to clean up the mess made when rich nations like Canada export their offenders.

“Tourism is not just a foreign exchange earner, where people come and see our scenery and culture,” Sereewat says.

“Wherever tourism is promoted prostitution is rampant. And children are falling into this. Can you have a law to stop [sex tourists], to hold them in the country and not let them go out? If your law cannot do that, then we can’t stop them.”

BACK IN CANADA, Prober’s goal is similar: to protect foreign children by strengthening laws against Canadian offenders. Among its efforts, Beyond Borders has lobbied for an end to house arrest for offenders of victims under eighteen. In 2002, thanks to pressure from her group, Canada’s child-sex tourism law was revised so that Canadians could be jailed for up to fourteen years for abuse committed abroad, whether or not the source country seeks punishment. The legislation was named the Prober Amendment in her honour.

Last June, Prober had another breakthrough. Due in part to Beyond Borders’ lobbying, the federal government introduced legislation to make DNA sampling and registration in the sex offender registry mandatory for all convicted sex offenders. Now, offenders who commit sex crimes abroad will automatically be added to the registry upon their return to Canada. And authorities will alert destination countries when offenders go abroad.

Prober is grateful for these small victories, but she’s still working to make the registry public and to bar sex offenders from all foreign travel. In her view, we have an obligation to do better. “We’re being selfish as a country if we say, ‘We could do something to protect your children from our sexual deviants, but that might take work and it might take money, it might take upgrading our laws, training our police, so we’re not going to bother.’”

There are also other signs of hope. The child-sex tourism law was upheld in court in late 2008 after a constitutional challenge from Kenneth Klassen, a father of three from Burnaby, BC who will now stand trial for offenses in Colombia, Cambodia and the Philippines involving girls as young as nine. Prober is also pleased that Ottawa’s National Child Exploitation Coordination Centre is widening its focus from child pornography to child-sex tourism. And she anticipates that a three-year awareness campaign that the Body Shop launched with Beyond Borders last year will bring the issue into the mainstream.

“It is slow, it is difficult, it is frustrating,” she admits. “But we are making progress.” Further proof, according to Prober, came with the case of Canada’s most notorious foreign child-sex abuser: Maple Ridge, BC teacher Christopher Paul Neil. Neil was the subject of an international manhunt after his face was digitally unscrambled from encrypted pornographic images involving boys as young as six. He was arrested in 2007 while hiding in Pattaya, and in 2008 was tried and convicted of abusing two Thai boys. He is serving an eight-year sentence in a Bangkok prison.

That trial would never have happened if the Thai boys had not come forward, Prober says. But they felt enough support from local non-governmental organizations (NGOs), the government, police, and Canadian authorities that they risked the trauma of testifying. “The easiest thing for those Thai boys would have been to walk away. But the message is coming through that the developed world has no tolerance for this kind of behaviour. That was a tipping point.”

ACROSS THE CHA PHRAYA RIVER, far from Bangkok’s seedy strips, Chakkrid Chansang sifts through case files. A member of the 29-year-old Center for the Protection of Children’s Rights (CPCR), the soft-spoken Thai lawyer has spent the past decade assessing the collateral damage of commercial sexual exploitation and helping rehabilitate the children it destroys.

The Centre is well-hidden in the warren-like streets of Bangkok Yai, and CPCR is equally careful in shielding its two shelters and their occupants—no outsiders are allowed. But Chansang spares no detail in describing the abuse survivors face, and how, as a result, they are becoming harder to help. “In the past, when they came to the shelter, children used to cry and say they were happy to be rescued. Nowadays the child says, ‘Why are you coming here? I want to work here.’”

The reason, he says, is traffickers are getting better at psychological games. They tell the children they need to work off a family debt, or claim they can leave anytime but will be arrested and beaten by police if they go. And then there is the cash. “Maybe they have to have sex with thirty customers to get 2,000 Baht [$62 CDN] per month,” Chansang says. “But then they compare this with life in Myanmar, where 2,000 Baht is very good. So when you come to rescue them they don’t want to cooperate, they don’t want to leave. Often the child who was rescued will say they had a good relationship and trust with their trafficker.”

Despite the difficulties, there are success stories. Chansang points to a recent case where a fourteen-year-old rural girl was offered a waitressing job in Bangkok. Her trafficker told her the job fell through, and promised to find her another in southern Thailand. She agreed, but instead was smuggled over the Malaysian border and shipped to Singapore, where she was kept in a guarded house with other girls and ordered to service men from a nearby construction site.

Desperate after seven months in captivity, she borrowed a cellphone from a Thai customer and called relatives, who urged her to escape. She bribed a guard, took a taxi to the Thai Embassy, and was brought to the CPCR. She spent two years recovering from her ordeal in a Centre shelter, suffering flashbacks and post-traumatic stress. Eventually, she found the resolve to testify against her captors. Thanks to her testimony, in 2008, her trafficker and two co-conspirators were found guilty and jailed. “She is,” Chansang says simply, “a strong lady.”

Happy endings like these are what keep frontline workers in the fight against child-sex tourism from giving up hope. ECPAT worker Vimala Crispin, who has run a program for rescued child prostitutes in Nepal, India and Bangladesh for the past three years, says she’s seen firsthand that victims of the child-sex tourism trade can recover and go on to live productive lives.

Take Maya, a girl from Nepal’s remote mountain region. At age twelve, she traveled to Mumbai, India, with the promise of a job from a family friend. She ended up in a brothel where a Nepali NGO found her at age seventeen, pregnant with an abuser’s child and HIV-positive. She recovered in a Katmandu shelter for several years before joining ECPAT. The first time they met, Crispin recalls, “this girl wouldn’t even sit down at the table. She went into a corner and wouldn’t talk. She was completely withdrawn.”

Slowly, as she trained to be a peer supporter to help other survivors and youth at risk, she came out of her shell: organizing projects, giving talks at local schools, moving out on her own, even meeting the president of Nepal to offer suggestions for fighting trafficking.

Maya’s attitude, like that of many child survivors of the sex-tourism trade, says Crispin, is this: “I don’t want to talk about all the misery that has happened to me. I want to do something about it. I want to make sure this doesn’t happen to my sisters.” Or to the three little girls still stuck in Pattaya’s mean streets, selling their flowers in a sewer.

Read the rest of Issue 35

Related on maisonneuve.org:

—Sympathy for the Devil

—The World Cup and the Spread of HIV

—Parental Espionage

Subscribe to Maisonneuve — Follow Maisy on Twitter — Like Maisy on Facebook