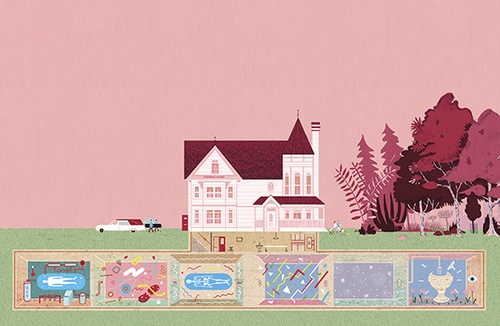

Illustration by Mike Ellis.

Illustration by Mike Ellis.

Reduce, Reuse, RIP

With Canada entering the Golden Age of Death, green burial options are going mainstream.

ON A NONDESCRIPT STREET IN PRINCE ALBERT, Saskatchewan, tucked between a strip mall and a low-rise apartment complex, there is a body dissolving inside a long steel cylinder. The chamber, a little larger than a coffin, has been flooded with water and alkali, then warmed to just shy of 100 degrees Celsius. As the body steeps, the tissues dissolve, leaving only bones, which are removed, ground up and crushed before they are placed into an urn and returned to the family: the cherished remains of a loved one. Another day’s work at Gray’s Funeral Chapel. This is alkaline hydrolysis, a newer, greener way to dispose of the dead.

Humans have found a way to strain natural resources even after we’re gone: over the past decade, conventional funeral practices—burial and flame cremation—have undergone environmental scrutiny. With Canada’s growing (and aging) population, this posthumous harm will only be amplified in the coming years. After factoring in the energy needed to operate the machine and manufacture and distribute the requisite chemicals, alkaline hydrolysis has roughly one-tenth the carbon footprint of its flame counterpart. But Drew Gray, the owner of Gray’s Funeral Chapel, notes that so far, the environmental motive is not usually the driving force behind most customers’ decisions to use the process; it comes down to personal preference. One person had a lifelong fear of water, so the idea of a water-based disposition didn’t sit well with the family. “But flip the coin—we had a man who was a firefighter his whole life,” Gray says. Unsurprisingly, the family decided to opt against burning his body.

The use of alkaline hydrolysis marks a major advancement in an industry that isn’t adaptive to change, but it’s not surprising that isn’t always marketed—or even regulated—as a new form of body disposal. Euphemisms for the process often carry a hint of the traditional: green cremation, bio-cremation, flameless cremation, or, as it’s called at Gray’s, water cremation. While new eco-friendly funeral alternatives have started to emerge as viable options, mainstream acceptance of these practices has proved more difficult. Any deviation from the norm requires an honest reflection about death, something that Joe Sehee, founder of the Green Burial Council (GBC), a United States-based organization that promotes greener funeral practices, says requires a cultural shift. “To some extent, we don’t really want to go near it. And I don’t blame people,” he says. As a consequence, societies tend to default to what’s comfortable, what’s traditional.

For alkaline hydrolysis, acceptance may be coming sooner rather than later. “There’s been a really good acceptance of the process,” says Gray. The funeral home had their alkaline hydrolysis machinery installed in March 2013, becoming the first in Canada to offer the service. Since then, about 120 bodies—60 percent of all their cremations—have been processed this way. The Cremation Association of North America has come out in support of the method, and has recently outlined suggested regulatory guidelines. Joe Wilson, CEO of Bio-Response Solutions, the manufacturer of Gray’s machine, reports that business has been picking up across the continent. Bio-Response now has thirty-five alkaline hydrolysis machines in operation: nine for humans, the rest reserved for pets. “We’ll probably double next year, and we’ll probably double again the year after,” he says. “I would say half the cremations twenty years from now will be alkaline hydrolysis.”

JUST A CENTURY AGO, cremation rates in the US and Canada were almost zero. Although humans have been practicing cremation for thousands of years (the earliest tracing back to around 3000 bc), it was phased out during the Christianization of Europe, after the Church deemed the burning of the body to be sacrilegious. When a resurgence in cremation began during the late nineteenth century, the Catholic Church moved quickly to prohibit the practice in 1886. It wasn’t until well into the latter half of the twentieth century that cremation rates started to soar (the Church ultimately relaxed its ban in 1963). Today, 60 percent of Canadians opt for flame over dirt after death, but cremation has its downsides. The emissions, particularly the mercury released from dental fillings, can cause air and soil pollution in the surrounding area, and the process uses a tremendous amount of energy.

For an environmentally minded person, burial procedures can also be difficult to defend. It used to be that we’d just dig a hole and toss the body in. Today, caskets are often ornate, made of precious materials including bronze, copper or steel—even gold is an option. And then there’s embalming, made standard during the American Civil War, when fallen soldiers had to be preserved to withstand the journey home from the front without decomposing too grotesquely. But these practices come at both a human and environmental cost. Sehee reports that funeral workers are at higher risk of nasal cancer and leukaemia caused by exposure to toxic embalming chemicals. There are also the chemicals in casket adhesives and finishes, which leach into the earth, and the carbon emissions associated with manufacturing. The impact is so great that in some states, the US Environmental Protection Agency has casket manufacturers on their list of top fifty hazardous waste generators. And then there are the burial vaults: concrete containers which serve as liners for graves. These vaults, which Sehee says are almost unheard of outside North America, are a huge drain on resources. “We’re currently burying enough concrete in vaults to build a two-lane highway halfway across the country,” he says. On top of all of that, there’s the water required to maintain perfectly manicured cemetery lawns. “It takes a tremendous amount of water to keep conventional cemeteries looking like coiffed golf courses, along with a lot of pesticides, herbicides and fertilizers.”

THE GREEN BURIAL MOVEMENT took off in the 1990s, with organizations such as the Natural Death Centre in the United Kingdom leading the way. Today the Natural Death Centre recognizes more than two hundred green burial sites across the UK. The US is slowly following suit with a few dozen sites, largely concentrated in the east and mid-west. But Canada has been lagging behind. There are only two cemeteries offering greener options that have been certified by the Green Burial Council, and both are in British Columbia.

The Woodlands burial site at the Royal Oak Burial Park in Victoria, BC, is unlike any other cemetery in the country. Young fir, alder and cedar trees grow over the graves, with native flowers and grasses acting as ground cover. Walking through feels like stepping into a forest. And that’s just what this graveyard is—a young forest. Families of the deceased stroll along the narrow paths lined with ferns and bushes, but they aren’t drawn to headstones. Instead of marked graves, there are a few simple communal stones stationed throughout the grounds, the names of those buried nearby etched in plain script.

This cemetery presents an entirely different approach to death. Instead of individually marked plots carving out a slice of earth for the deceased in perpetuity, the whole forest stands as a living memorial to the dead. The desire here is not to preserve one’s body, but rather to facilitate its decomposition—to help death bring about new life.

In a green burial, the body is prepared without the use of any embalming chemicals. No concrete grave liners are used. The casket—if one is used at all—is biodegradable, made of sustainably harvested wood. Indigenous plant life is left to grow on the gravesite, letting the cemetery become a nature preserve. The Royal Oak Burial Park was the first in the country to offer green burial in an urban environment. Stephen Olson, executive director of the Royal Oak, says almost all of its 245 plots are either in use or pre-sold. But this is just the first phase of development: they have committed to using half of their undeveloped lands for future green burial. “We knew there was some interest,” Olson says, “but we never anticipated this much.”

The green burial movement extends beyond environmentalism: its practitioners have been creating a more participatory experience for families—one that Sehee says can be enormously cathartic. Olson says that families find tremendous comfort in this idea. “That’s their loved one literally contributing to the prosperity of the natural landscape.” Friends and relatives are able to create the type of funeral that best facilitates their grieving process. “It’s about giving the family permission,” Olson says. “As soon as you open the door a crack, they will come back to you and say ‘Can we do this,’ or ‘Can we do that?’ They suddenly become more involved.” Some families build their own casket. Others make their own burial shroud out of natural fibres, in which they themselves wrap the body. A friend or sibling might help plant the gravesite with appropriate indigenous flora. Whatever the activity, they all encourage an active acknowledgement of the realities of death for those left behind.

Unfortunately, green burial isn’t an option if there’s no local site—as is the case across most of Canada. The frustration over a lack of green burial space is familiar to Rick Zerbe Cornelsen, a natural casket maker in Winnipeg. He became involved in casket making when his father made his mother’s casket out of reclaimed wood. The simplicity of the design and the intimate nature of the process helped prompt Cornelsen, a woodworker, to start creating caskets of his own. “When I first started, the eco-friendly, all-natural element was in my mind, but it was not the first thing that drove me to this. The idea was that I wanted to offer something local and hand-crafted and relatively simple,” he says. Although his first caskets were simpler than the conventional options and used fewer resources, they still featured wood finishes and metal components. But as Cornelsen became more invested in the idea of green burial, he came up with the TimberWise casket. This product is made of certified sustainable softwood. There is no metal; even the handles are made of sisal rope. But without any green burial sites around, Cornelsen’s efforts can only do so much. “So far, most of my TimberWise caskets have been used in a conventional cemetery. It still means fewer toxins going into the ground. But it’s not ideal,” he says. “We could do so much more.”

WILSON, OF BIO-RESPONSE SOLUTIONS, identifies the regulatory process as the biggest obstacle preventing widespread access to alkaline hydrolosis. The disposal of human remains is overseen at the provincial level in Canada and at the state level in the US, and not all jurisdictions have passed the necessary legislation. As regulation procedures slowly get underway, discomfort with alkaline hydrolysis has started to show, particularly among religious groups. The New York Catholic Conference put out an official memo of opposition in 2012, citing that the process lacks dignity. But there’s something discomforting about many of the things that people do to the dead. Being shoved in a furnace and burned isn’t exactly cheery. Neither is being drained of all natural fluids and pumped full of embalming chemicals. Gray points out that disposing of a body, however it’s done, is a distasteful reality. “But we have to deal with that body,” he says matter-of-factly.

If Canadians want more green alternatives, Sehee says they will have to start demanding them. And this means that Canadians will need to start thinking about death—not an easy task. “We want to focus on living, not dying. And no one wants to plan their funeral. But solace can be found in befriending death,” Sehee says. To this end, the GBC has been working on advocacy through industry training and public education. The goal is to make people more aware of their options and their impact after death.

Cornelsen, Olson and Sehee all predict that the shift toward green burial will come along generational lines. “I think we’re still five or ten years out,” Sehee says. “Baby boomers going into the grave in a big way is really what changes things.” Over nine million people strong, the boomers make up almost a third of Canada’s population. They have a lot of sway—and their own way of doing things. “Baby boomers have chucked at every cultural milestone they’ve met,” Sehee says. “They don’t really care to be buried in their families’ cemetery. They want to do something that they think is aligned with their core values.” Next year marks the seventieth birthday of the first boomers—meaning Canada will be entering what has been called the Golden Age of Death. As this cohort marches further toward its end, change appears inevitable. “We’re starting to see a culture becoming receptive to talking about end of life issues,” Sehee says. “And I think the conversation is really just getting started.”