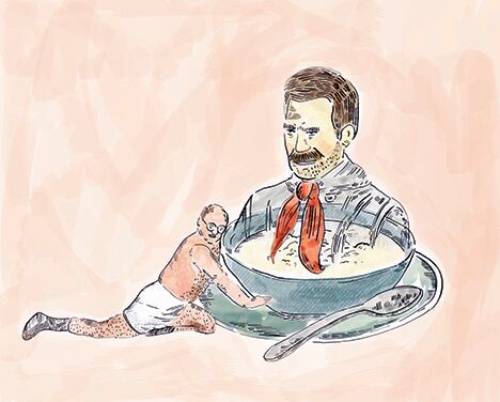

Illustration by Carolyn Figel.

Illustration by Carolyn Figel.

Jerry Rigged

It’s easy not to be the butt of the joke when you’re the one writing it. Why Seinfeld’s comedic brilliance relied on a privileged perspective.

IF YOU PLEASE, let us examine the tale of two Twitter feeds: Modern Seinfeld (@SeinfeldToday) and Seinfeld Current Day (@Seinfeld2000), both of which imagine what the canonical sitcom would look like if the series had continued into the present. @SeinfeldToday’s TV Guide-style episode descriptions substitute contemporary reference points into classic Seinfeld-esque plots (e.g., “George goes to war with an evil barista who writes embarrassing things on George’s cup instead of his name”), while @Seinfeld2000 takes the same concept and dunks it into the oozing miasma colloquially known as “Weird Twitter,” with dumb jokes, intentionally awkward grammar and misspelled names: “Elane cop the new kendrick on vinyl” reads one recent tweet (the accompanying Photoshopped image shows Julia Louis-Dreyfus plotzing over a copy of To Pimp a Butterfly).

Seinfeld has endured to the point that it’s considered an untouchable classic—a high-water mark in the history of American television. Criticisms have been few and far between, although during its primetime run a few writers picked up on the insularity of its onscreen world and how solipsistic it seemed next to the expansive social visions of The Simpsons and South Park. On the recent Saturday Night Live 40th Anniversary Special, Jerry Seinfeld addressed this skepticism by responding to a (scripted) question from Ellen Cleghorne about the lack of black characters on the show: “We did not do all we could to cure society’s ills, you are correct—mea culpa.”

Whether or not this comeback was meant to be a joke, it rubbed plenty of people the wrong way. For those of us who’ve never really liked Seinfeld (or Seinfeld) that faux-contrite response was an extension of an uptightness that went beyond a comic posture—it was an affirmation of arrogance. This above-it-all-ness was hardly a liability during Seinfeld’s run; if anything, it was a point of satisfaction. By crafting endlessly reiterative vignettes about the greed, vanity, laziness and other deadly sins of affluent city-living schmucks accosted at irregular intervals by a host of stereotypically ethnic and invariably hysterical New Yorkers, Seinfeld and Larry David angled the proverbial mirror so that it reflected their own lives.

They also found a way to consistently honour the ancient comedy koan of “it’s funny because it’s true.” In its way, Seinfeld was a model of audience relatability. Who hasn’t misplaced their car in an underground garage or broken off a casual fling for improbably petty reasons? (Admittedly, it’s probably rarer to know somebody who’s dropped dead licking toxic envelopes but the point remains: tragedy touches us all.) The details of the different dilemmas are heightened but fundamentally authentic; the mechanism that keeps kicking all those Rube Goldberg plots into high gear is a base selfishness that typically mutates from relatable to monstrous around the time of the second commercial break. When four such insatiable ids were in collision, as they were in the funniest and most frenetic episodes, the tension was bristling and exhilarating—or enervating, depending on your taste.

AS A SEINFELD SKEPTIC, I realize I’m fighting a losing battle: to deny the show’s brilliance on the levels of writing and ensemble acting is churlish and false—a pedant’s miserly errand. But Seinfeld’s proudly brandished mission statement to be a “show about nothing” has had a net negative effect on modern comedy, specifically in its misprision of irony. The twisty scripts that subjected Jerry and his friends to all sorts of intricate indignities surely fit the Alanis Morissette definition of irony as some sort of late-breaking inconvenience—like rain on your wedding day, or a free ride when you’ve already paid—but the classical notion of feigned ignorance or indifference concealing an urgently perturbed worldview is nowhere to be found. And while critics frequently made reference to the show’s use of satire—as in its skewering of social rituals (dinner parties, workplace meetings) and public figures (George Steinbrenner, J. Peterman)—the jokes fall far short of Northrop Frye’s contention that satire is “militant” irony, exercised in the hope of instigating change.

CHANGE IS A DANGEROUS THING in the situation comedy universe, where familiarity breeds content. Sometimes this stasis can be mined for humour, as on The Simpsons, where Lisa comments that one of the family’s adventures seems to be wrapping up earlier than usual, or Louie, which openly mocks the notion of continuity within individual episodes and entire season-long arcs. Seinfeld’s innovation was to create a set of protagonists whose flaws and neuroses would be so venally endearing that the very idea that they might grow or mature beyond them was more horrifying than their worst behaviour. The supporting characters who blew in and out of the show were mostly hapless innocents whose naïveté made them fair game for shenanigans, or else villains so vile (hello, Newman) that they doubtlessly deserved even worse than our antiheroes. There’s a technical term for this sort of strategically slanted dramaturgy: having your cake and eating it too.

Never was this particular strain of gluttony more apparent than in Seinfeld’s finale, which saw Jerry, George, Kramer and Elaine sentenced to communal jail time for criminal indifference—a nicely sideways evocation of Jean-Paul Sartre’s No Exit and its “hell is other people” kicker that gave the final pullout from the gang kibitzing behind bars a slight fritz of existential resonance. The trial was meant self-reflexively as a referendum on the show, and even though the characters were found guilty after a parade of surprise witnesses claiming victimization, the case was actually being made for the defence: the only thing that Seinfeld (and Seinfeld) is truly guilty of, Your Honour, is nine years of hilarity. Any objections on moral or intellectual grounds are beside the point, because there’s nothing you can say about our clients that they haven’t already admitted of their own volition—and with nice, big, shit-eating smiles on their faces, too.

MAYBE IT’S THAT GRIN, Jerry’s default setting as both character and actor, which explains why I hate Seinfeld (and Seinfeld). It’s the thin rictus of a front-runner whose indifference and ignorance is never feigned. Instead, it’s triumphal, overlaid by the faintest hint of self-deprecation. Jerry and George are such vain, self-centred assholes that they can’t hold on to the beautiful girlfriends who keep falling at their feet, or else they beg our sympathy as they scheme to extricate themselves from these women’s interchangeable embraces. It may also be that my antipathy to Seinfeld comes out of the same sense of recognition that makes others love it: that I feel implicated by all the glib, shallow goings-on. But the reason I love The Simpsons and Louie is because they present a gallery of human types. Homer Simpson doesn’t change, but that doesn’t keep Lisa from trying to move that needle; Louis CK has taken the basic Seinfeld model of a successful stand-up “playing himself” in New York City and torqued it into a strangely humane vision of human frailty which locates cruel comeuppance as just one of many points on its moral compass. And Broad City, a spiritual sister to Louie, reclaims the lazy misogyny of Seinfeld in its vision of twin Elaine Beneses who wouldn’t be caught dead wasting time with the likes of George Costanza (although Hannibal Buress’ “al dente” dentist Lincoln is a worthy successor to Kramer in the hipster-doofus pantheon).

So I prefer these shows to Seinfeld, and I prefer @Seinfeld2000 to @SeinfeldToday because it skimps on the reverence for a show whose mix of narcissism and non-committal nastiness has left it safely ensconced as a classic. As of this writing, the pinned tweet on the @Seinfeld2000 page, with characteristic misspellings and poor grammar, reads as follows:

Jary gaze wistfuly at his own reflectien in the miror

JARY: Whats the deal ... with me?

He search his sad eyes for an answer but find none.

You better believe one of the 1,300 favourites is mine.