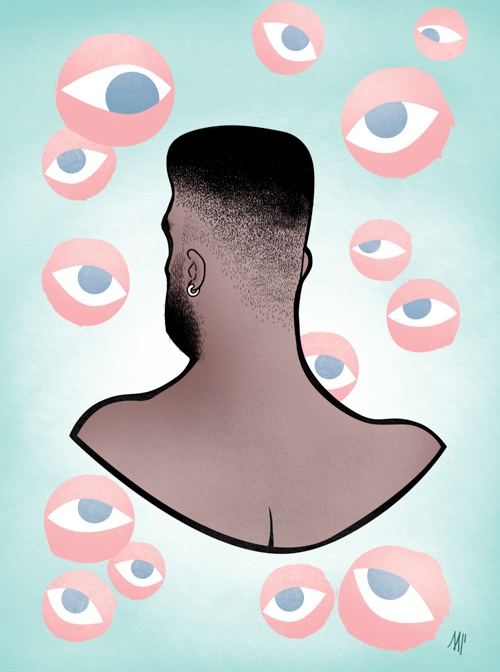

Illustration by Mauricio Naranjo.

Illustration by Mauricio Naranjo.

It Takes the Village

Straight tourists and gawkers are flocking to Montreal’s LGBTQ neighbourhood, while the queer community disperses for new haunts. Tim Forster on the double-edged sword of mainstream acceptance.

It’s a Wednesday night at Cabaret Mado, a well-known venue for drag shows in Montreal, and a crowd has gathered to fundraise for a student society at a nearby university. The bar looks like an appropriately campy setting, even from the outside, where a large plastic sculpture of Mado, the cabaret’s eponymous drag queen, falls backwards from her perch on the venue’s sign. Mado has regularly been voted one of Montreal’s tackiest personalities in a local alt-monthly, and the sculpture explains why: the plastic Mado sports purple hair, six-inch stilettos, a large bejewelled ring, a silky-satin dress, pearl necklace and eyeliner aplenty.

Walk inside and the bargain glitz continues. A disco ball and strobe shower the room in sparking light, and spotlights bathe everything in a pink hue. Without the lights, Cabaret Mado could pass as a dive bar that occasionally hosts a Led Zeppelin cover band: chairs and tables haphazardly scattered in front of an austere stage; video-poker machines tucked partly out of sight in a corner and used primarily by solitary older folk.

On this particular night, the décor and ambience serve to draw eyes to Tracy Trash, the drag queen and hostess for the evening. At centre-stage, sporting a red sundress, Trash towers over a large group of moderately macho young men, bantering with the crowd and lip-syncing to a varied medley—there’s the Cats ballad “Memory,” “Lady Marmalade” and a saccharine hand-clappy pop hit from American chart-topper Meghan Trainor. In between two of these tracks, Trash approaches the front-row bros, teasing them as a few of their friends and girlfriends around the room giggle. When she asks them upfront about their sexuality, they admit they’re straight.

Cabaret Mado is in the heart of Montreal’s Gay Village, midway down a kilometre-long strip of nightlife spots on St. Catherine Street East that runs from St. Hubert to Papineau. Despite its location and theme, though, you’d be hard pressed to label it a gay bar on this particular Wednesday.

According to owner Luc Provost—better known by his eponymous drag name, Mado Lamotte—straight men are a common cabaret sight in 2016. “They used to come here to make fun of us,” he explains, “but more and more they come here and they talk to the manager and say, ‘we’re a bunch of guys for a bachelor party, do you think Mado can make fun of our friend?’”

Over the years, Provost says, LGBTQ people have slowly become a definitive minority of Cabaret Mado’s patrons. “When I started, it was a little bit more gay,” he says. “Now I would say it’s probably 80 percent heterosexual girls.” Lynn Habel, a representative of Tourism Montréal who is responsible for researching and promoting the Village, has also observed that straight women like the clubs in the area. “The music’s good,” she says, “and the men are actually really nice to them.”

Mado isn’t the only place that’s witnessed a decline in its gay patronage. At the east end of the Village, a huge, whimsical red brick building has stood empty since early 2014. It used to be the Complexe Bourbon, containing multiple bars and restaurants as well as a hotel—what its former owner described as a “gay Disneyland.” A few months before the Complexe Bourbon closed, the four-storey lesbian bar Le Drugstore was also shuttered. A straw poll of LGBTQ Montrealers suggests that other big venues, such as Unity nightclub or the multi-level Complexe Sky, now feature more mixed crowds. And while homophobic and transphobic violence in the Village still surfaces in the news periodically, such attitudes tend to be widely condemned, especially in hyper-liberal Montreal. As a result, straight people are less wary of entering gay spaces, and gay people are happier to let them in. But when the neighbourhood is constantly filled by heterosexuals, is it even a Gay Village at all?

When the “Gay Village” appellation first began to stick, the neighbourhood’s social sphere was dominated by LGBTQ people, especially gay men. Whether or not LGBTQ people actually made up a majority or plurality of the area’s population is a difficult question: the Canadian census does not gather information about non-binary gender identities, and only counts LGBTQ people who declare themselves to be married or in common-law relationships.

Even if there’s no way to reliably quantify the Village’s gay identity with census data, one assertion about that identity is true: it only came about in the 1980s. Before that, and especially in the mid-twentieth century, queer life was centred in unofficial, gender-segregated bars, such as the El Dorado Café (popular with younger gay men) and Le Zanzibar (which drew more women) in Montreal’s downtown core. According to retired McGill University sociology professor Don Hinrichs, author of Montreal’s Gay Village, these bars offered valuable meeting spots. “You don’t generally meet a gay person in church,” he says.

By the late 1970s, a combination of police raids on gay venues—including the infamous raid at Truxx in 1977, which led to 146 arrests—and then-mayor Jean Drapeau’s anti-gay policies (he famously ordered thousands of trees to be cut down from nearby Mount Royal so that men couldn’t cruise for sex beneath the foliage) had driven these bars out of downtown.

The bars, and the gays, established themselves further east in the 1980s. The neighbourhood’s “Village” moniker was borrowed from the now-defunct porn theatre Cinéma du Village. Previously a rougher, working class neighbourhood, the Village’s commercial strip on St. Catherine flourished under an influx of businesses. Hinrichs highlights attempts to start a gay mall in 1986, and also the relocation of Priape to St. Catherine, which became the Village’s flagship sex shop. Through interviews with members of Montreal’s queer community, Concordia University professor Julie Podmore has been able to plot the evolution of the Village from the late 1980s. “People started to open gay specialized services, like a gay photocopying store,” she says. In turn, those commercial agglomerations served as beacons, indicating a place where isolated LGBTQ people—particularly francophones—could find acceptance. “If you’re queer and you [were] immigrating from Rimouski,” she says, “this is where you [were] going to find community and connect with other people.”

In 2016, the Village beacon doesn’t shine as brightly. “For rent” signs and sun-bleached rainbow flags dot the street’s storefronts. Oasis, one of the main saunas (with its suggestive slogan “pour la crème des hommes,”) is plastered with mock screenshots of a borderline defunct gay smartphone app. On a summer day when the street is lively, it could generously be described as having a rustic charm. In the depths of winter, though, it’s downright desolate.

Hinrichs’ interpretation of the district’s fading character is that the residents who put the “Gay” into the Village have simply moved on in their lives. He says it’s partly a question of whether the Village is a good place for families. “Most gays and lesbians with families and children say it’s not a good place,” he tells me as I sit in his apartment living room, a kilometre east of the Village. “Do you want to live in a condo very close to where all the bars are, and at 3 am people come out on the streets?” Hinrichs has noticed a lot of gay men moving farther out, towards where he lives. “We have gay neighbours now, which we didn’t have [before],” he says.

It’s a movement that Podmore has observed, too. She has identified three parts of the city that have been attracting specific LGBTQ groups in recent years: the east (where Hinrichs lives) is popular amongst younger francophone gay men; St. Henri, in the city’s southwest, has drawn transgender people; and the Mile End and surrounding areas north of downtown is home to anglophones, particularly those who identify as queer (in contrast to “gay” or “lesbian”).

Podmore posits two explanations for an apparent gay exodus from the Village: like Hinrichs, she suggests that older individuals who settled there in the 1980s and 1990s are now less interested in living downtown and close to bars. As for the younger LGBTQ crowd, they view sexuality and gender identity differently from their predecessors—these identities aren’t passed down through generations the same way as ethnicity. While the older gay generation developed a connection to the Village, younger groups have found those geographic connections elsewhere. The trend towards adopting a “queer” identity—where sexuality is seen as fluid and not rigidly defined as “gay” or “lesbian”—has also contributed to the move away from the specifically “Gay” Village.

However, there is one group who Podmore has seen populating the Village in droves: tourists. “I don’t just mean LGBTQ tourists from elsewhere,” she says. “I also mean people who want to consume diversity in Montreal, maybe coming from the suburbs to spend an evening downtown, which changes the social dynamic.” The Village has become a stop for tour buses from other parts of Canada and the United States, depositing stag and bachelorette parties. “You’ll see those groups of people sort of invading the space as a ‘fun’ space, and you see the contrast between them and elderly gay men who built the Village sitting there and feeling kind of threatened by that,” she says.

According to Podmore, hand-wringing about the Village’s “de-gaying” is not new: in the past, she says, the Village catered more broadly to all the letters encompassed by the LGBTQ initialism. Throughout the 1990s, as the Village diversified and picked up economic steam, lesbian- and gay-coded spaces receded in favour of mixed spaces that Podmore says were “usually quite gay-oriented.” Finally—slowly, and then at all once—the Village’s bars, clubs and after-hours clubs surrendered their majority-queer territories, becoming, as Podmore describes, “very heterosexual.”

Tourisme Montréal, the non-profit body responsible for marketing the city, has classified the Village as a tourism district for about twenty years. Initially, the Village was marketed to queer tourists, says representative Lynn Habel. But that started to shift in 2006, when Montreal hosted the Outgames, a sort of gay Olympics. A section of St. Catherine Street in the Village was designated pedestrian-only as part of a fundraiser, and when it proved popular, the feature became part of the Village’s summer calendar.

A pedestrianized street alone does not draw tourists (a few kilometres north, the St. Hubert Plaza, known for its wig stores and tacky prom dress boutiques, periodically closes to traffic, but it hasn’t winded up on the tourist map). But the Village has an added drawcard: the Boules Roses. Part of the neighbourhood’s open-air art installation series, Boules Roses consists of 170,000 plastic pink balls strung above the street to create a one-kilometre long ribbon-cum-canopy over the car-free road. Claude Cormier, the landscape architect who designed the installation, says that he chose pink as the “most gay” colour he could use. Initially, Cormier intended to instil a sense of ownership, pride and community in the Village. The spectacle of thousands of pink baubles floating in mid-air also proved popular for tourists.

The balls are paid for by the Village’s merchants’ association, the SDC du Village, which is funded by a mandatory fee collected from all businesses on the pedestrianized strip of St. Catherine. Like any merchants’ association, the SDC aims to promote business, and the pedestrian-street-plus-Boules combo has done exactly that. “You cut that pedestrian street and we’re all going to close our businesses and go back home,” says SDC president Denis Brossard.

As a free attraction, Cormier’s Boules doesn’t directly inject money into the economy. Indirectly, though, it’s a goldmine. If businesses can convince visitors to take a seat at their open-air terrasses and soak up the atmosphere, those visitors will throw down money on meals and drinks. The influx is clear to Natasha Clayton, who has spent years working at art and homeware store Albatroz: she estimates one in five shoppers in the summer months are tourists. That’s a sharp contrast to just a decade ago, when Clayton remembers the Village as having a much larger gay presence. For businesses that focus specifically on gay clientele, this shift has necessarily impacted their bottom line; for others, it raises uncomfortable questions about the intersections of capitalism and identity, acceptance and selling out.

The Village’s demographic shift is not unique to Montreal. In his book There Goes The Gayborhood, sociologist Amin Ghaziani suggests that queer neighbourhoods are moving towards being centres for gay-oriented businesses and away from being hubs for an entire community. Much like how suburban car dealerships can often be found lined up next to each other on a highway, he writes, gay bars will stay clustered together even if the neighbourhood’s LGBTQ residents disperse.

But Podmore suggests that for a variety of reasons, the need for queer people to hang out in the Village has waned. The Village’s queer edge lives on mostly in the form of a fondness for the past. “When I go to the Village, I think this is not a place as a queer person that I even feel I belong in anymore,” she says. “My connection to that place is memory, mostly.”

When queer-focused events do take place in the Village, they usually include increased participation from straight people. The most obvious example is Pride: throughout the summer, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau marched in three separate pride parades, including Montreal’s. Such decisions style him as modern and “with it,” while simultaneously contrasting him with his predecessor Stephen Harper. Trudeau is the future, and the future loves gays.

Similarly, following the June massacre of forty-nine people at a gay club in Orlando, Florida, straight politicians including Montreal mayor Denis Coderre, Heritage Minister Mélanie Joly and Quebec Premier Philippe Couillard turned out en masse for a vigil in Montreal. Some of them spoke before a crowd of hundreds, clutching rainbow flags and candles. (Flash back to the 1980s, and far fewer politicians were clamouring to be seen at an HIV-AIDS vigil.) The message they were conveying to LGBTQ people is clear: You’re safe with us. By extension, it seems reasonable to suggest that some LGBTQ people might feel that they’re more accepted than ever in society, and may now leave the Village and its protections behind.

Of course, the LGBTQ population is not monolithic. At the end of that same Orlando vigil, a young trans activist named Esteban Torres took the presence of a crowd as an opportunity to express his discontent, shouting “We will take back the street!” and throwing a ball of paper at Couillard before a low-key melee resulted in his arrest. While the purpose of Torres’ protest was never entirely clear, support he received from anarchist groups suggests he was arguing against an increased police presence in the Village, which had been promoted by a local community group.

It would be easy to write Torres off as a lone wolf, particularly on account of his inarticulate dissent. But as a trans activist, Torres clearly didn’t feel welcomed into the liberal fold. Moreover, his anger is emblematic of other young, radical queer people who have gone out and created their own spaces, separate from the Village.

In some ways, the incident and responses to it are an extension of the interminable arguments about assimilation in LGBTQ circles: conservatives argue that queer people should adjust to fit in with straight society, seeing those who are “too gay” as being too radical for their own good. On the flip-side, the “radicals” argue that queer people have fundamentally different life experiences than heterosexuals, meaning they require separate queer spaces; they might even say that the conservatives are simply wannabe straight people.

Starting about three kilometres northwest of the Village lies a string of three neighbourhoods: Mile End, Mile Ex and Parc Extension. The three form the heart of Montreal’s contemporary queer scene, though its presence here isn’t visibly demarcated in the same way as it is in the Village. Certain markers—piercings, coloured hair, tattoos, denim cut-offs—are frequent, although they’re hardly exclusive to the queer community.

If you stroll around the slightly ramshackle post-industrial lofts of the Mile Ex on a weekend night and keep an ear open for thudding electronic beats, you might well find a queer scene party with a higher proportion of LGBTQ revellers than is the new norm at a Village club. They’re often underground, in not-quite-legal venues; at one popular spot, if you arrive between 1 and 6 am, you’ll descend into the basement and walk right onto a concrete dance floor in a fairly dim room, populated by a writhing crowd. Walk to the back and you’ll find a lounge-type space. Depending on how strict the organizer is, you might find people smoking inside and drinking their own booze; “extra-curricular” substances are common, too.

J’vlyn d’Ark is a DJ who puts on these parties from time to time. D’Ark contrasts these spaces to the rapidly straightening gay clubs of the Village by highlighting the crowd who attends: fewer men, a range of genders and people who don’t fit neatly into a binary of man/woman or gay/straight. For d’Ark, the Village’s transition to a mostly straight crowd does not mean that everyone on the LGBTQ rainbow feels wholly integrated into society—especially those who don’t fit into more mainstream gay scenes. “There’s a reason we keep coming back to queer spaces,” d’Ark says. “As long as we are still being oppressed in our day-to-day lives, there’s always going to be a need for that healing effect of being around people who share that experience.”

D’Ark is cognizant of the growing interest in the queer scene though, and the possibility that straight folk could just as easily be drawn into the liberated space of an underground rave she organizes, but she welcomes the opportunity to offer them a space to experiment. “The sad but very true reality of our world is that we are all determined straight and assumed straight until we define ourselves as not,” she explains. “A lot of those straight people are coming to be queer for the first time and they should get to do that.”

There’s one key difference between d’Ark’s queer parties and the bachelor(ette) partiers who might hit a Village club: the brides- and grooms-to-be and their friends are slowly converting Village clubs into straight venues, whereas d’Ark is subsuming straight people into an overwhelmingly queer space.

Mile-Ex Queer parties are still relatively tourist-free. While the neighbourhood was written up in Vogue last year as a hip place to visit, it hasn’t yet been recognized as a nightlife destination.

Head back south and the irony of the Village’s dual identities of “gay” and “tourist attraction” becomes clear. The Village’s tourist appeal hinges primarily on its gay identity—from Cabaret Mado (rated four-and-a-half out of five on TripAdvisor) to the pink balls—even as its gay identity fades.

To combat this, some community figures have suggested establishing a community centre to transplant a permanent LGBTQ heart into the Village. It’s an idea that local city councillor Valérie Plante supports enthusiastically. Further, the Village’s side-streets are home to a range of LGBTQ advocacy groups, such as youth organization Projet 10 and gay public health network Rezo, and Plante would like to see these sorts of groups, as well as regular residents of the neighbourhood, consulted more about development in the area. But with condos already starting to sprout, it may be too late.

Unfortunately for Plante (a member of Projet Montréal), her political party doesn’t hold power at City Hall. Instead, Richard Bergeron, the member of the city’s executive committee responsible for developing the downtown core, has expressed support for a plan to link the Quartier des Spectacles entertainment district with the Village, providing it with a continuous pipeline of tourists.

This sort of touristification of large urban swathes is something that Plante says isn’t good policy for the city. “We don’t want to have a Venice where nobody lives in the city anymore and it’s only a city for tourists,” she explains. But if you ask Podmore, the city looks set to continue taking (or mistaking) the voice of those who cater to tourists as the authoritative voice of the Village. “Their interests are very much privatized interests,” she says of the Village’s merchants’ association. “I think what they would like to see is a completely festivalized space in the Village, clear of any persons who are not engaged in the particular practice of consumption that they are envisaging.”

As long as straight tourists continue to be interested in consuming the Village and its identity, the Village will continue to seem gay. But this is only a façade, supported by 170,000 bright pink balls and a whole lot of string. Should the installation be disassembled, the neighbourhood may find it has no core identity left at all.