Illustrations by Glenn Harvey.

Illustrations by Glenn Harvey.

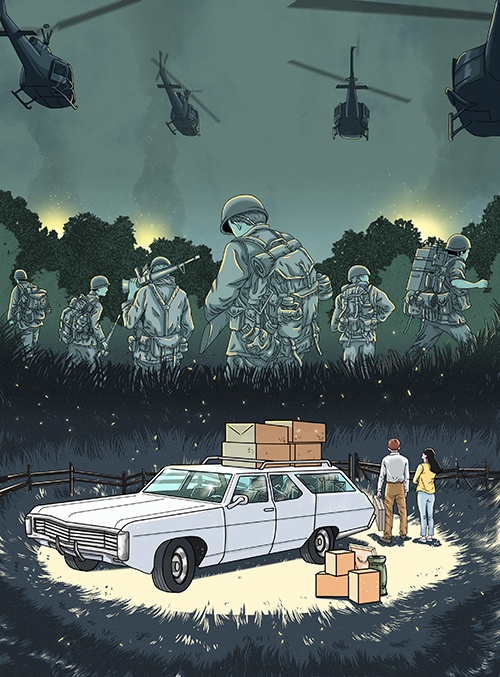

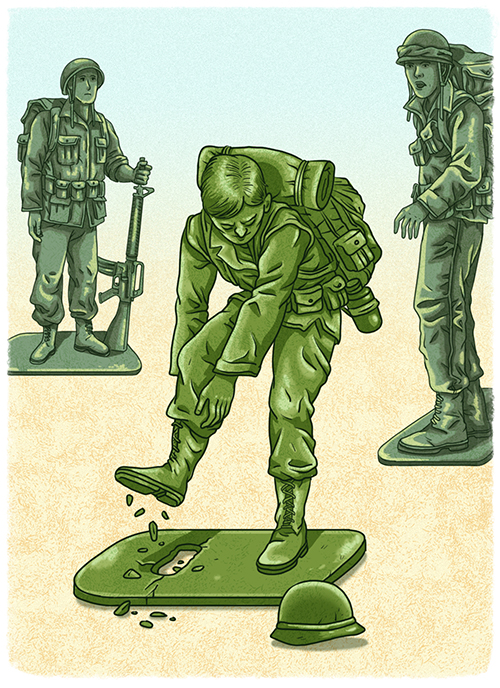

Last-Generation Americans

Fifty years after the Vietnam War, Anders Morley talks to draft dodgers about their legacy in Canada.

Early in February of 1969, five York University students entered the United States at separate points along the Ontario border, then turned promptly around to return home. Each of the five identified himself as William John Heintzelman at Canadian immigration and presented documentation validating this stated identity.

The real Heintzelman was a deserter, on unauthorized leave from the United States Air Force. His impostors sought entry to Canada as landed immigrants, a simple procedure at the time, for which they had the requisite offer of employment. All five young men successfully impersonated the American but were refused entry when they could not offer proof of military discharge. In at least two cases, the students were handed over to US immigration officials, who had been informed of their rejection by telephone.

The experiment furnished definitive proof of what Toronto Star journalist Ron Haggart and anti-draft activist Bill Spira had been saying for months—that immigration officers had been violating the Immigration Act by following secret directives designed to keep American deserters out of Canada. The covert protocol was also at odds with public opinion; according to sociologist John Hagan’s research, which samples letters sent to Allan MacEachen, then-Minister of Manpower and Immigration, Canadians increasingly felt that American military deserters should be treated like draft dodgers, to whom Canadians were sympathetic; both dodgers and deserters were, at the heart of it, war resisters, and whether they were civilians or soldiers should have no bearing on their status in any country but the United States.

This publicity stunt was described in detail by one of the participants, Bob Waller, in the Montreal Star the following day. Over the following months, the United Church of Canada, the NDP, and certain segments of the press and academia applied consistent pressure to the wavering Trudeau government to officially reject the idea that Canada had any role in enforcing the domestic laws of the United States. Political economist Stephen Clarkson voiced what many seemed to be wondering in an op-ed for the Toronto Star: “Is [the Trudeau government] going to adopt a coherently liberal policy or is it, like the well-trained concubine, going to pander to its master without even being asked?” The Globe and Mail’s editors pointed out the illegality of the protocol, writing, “If the Government wants to exclude deserters it can do so legally only by changing the Immigration Act or by altering its extradition treaties.”

The government eventually relented. On May 22, 1969, MacEachen told the House of Commons, “Our basic position is that the question of an individual’s membership or potential membership in the armed forces of his own country is a matter to be settled between the individual and his government.” Between April and August of that year, the number of draft-age American men entering Canada each month as landed immigrants tripled.

The northward trickle of US war resisters had begun in 1964, the same year that President Lyndon B. Johnson’s Gulf of Tonkin Resolution prompted the massive escalation of US troops in Vietnam. Over the next decade, this influx of young immigrants burgeoned into what Hagan has called “the largest politically motivated migration from the United States since the United Empire Loyalists moved north to oppose the American Revolution.” Hagan estimates that sixty thousand young American men and women resisting conscription laws or military service and one hundred thousand Americans of all ages fleeing as a more generalized act of protest eventually made their way to Canada. The year 1969 was the first since 1932 when more people immigrated from the US to Canada than in the opposite direction.

Among these exiles were some remarkably gifted individuals. An inordinate number ended up in writing, publishing and media; university and college faculties famously filled with them, to the point that it seems most students who have passed through one of these institutions in the past fifty years remember at least hearing rumours about a draft-dodger professor. Unsurprisingly, they also made notable contributions to social-justice activism. Some even entered politics and the civil service. Most of the Vietnam-era war resisters who stayed here, however, settled into lives as ordinary citizens, part of the fabric of everyday life. Collectively, however, they became a symbol and a vector of a changing Canada. Their experiences of resistance helped usher in a progressive new identity for a country that was coming of age, just as they were.

There are still traces of New England in Richard Paterak’s speech. Paterak, who grew up in Massachusetts, graduated from Marquette University—alma mater of Joseph McCarthy, who put to flight a previous generation of dissident Americans—in the spring of 1965, a few months before President Johnson increased the monthly draft call-up to thirty-five thousand men. Paterak immediately joined the Volunteers in Service to America (VISTA), a federal program launched earlier that year to fight domestic poverty. During a training program in Philadelphia, he met his future wife, Arlin. A later assignment took them to Chicago’s West Side to work with the American Friends Service Committee.

Paterak knew he was eligible for the draft and suspected that the deferment he’d received to pursue his VISTA work would be exhausted after a year. He viewed participation in the war as immoral and had resigned himself to the inevitability of prison.

Then, in September 1966, Paterak came across an article in the Chicago Sun-Times about Tony Hyde (better known today as Anthony Hyde, spy novelist) and American draft resisters fleeing to Canada. Hyde worked for the Student Union for Peace Action (SUPA) in Toronto, assisting American resisters with the particulars of setting up in exile. Canada held a romantic appeal for Paterak, whose mother’s family had first immigrated to New France in the seventeenth century before eventually moving to New England. In addition, Paterak says Arlin “was not enthused at the prospect of waiting around in some backwater minimum-security-prison town while I served my sentence.”

With a pair of university degrees and about $2,000 between them, all the couple needed to do was fill out a form to present at the border. They notified friends and employers of their departure, bought a 1955 Oldsmobile and drove to Windsor via Detroit. They were granted probationary entry, pending satisfactory chest X-rays showing no tuberculosis. “We took the tunnel rather than the bridge,” Paterak says, “because I liked the symbolism of going underground.”

From there, they headed for Toronto. As soon as they arrived, they paid a visit to Tony Hyde at the SUPA office at Spadina and Harbord. Established in 1964 as an outgrowth of the Combined Universities Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, SUPA was an attempt to broaden the struggle against militarism and imperialism using the participatory-democratic approach of the US-based Students for a Democratic Society (SDS). In the fall of 1965, SUPA had launched an initiative to lend assistance, counsel and support to the mounting tide of draft resisters. Paterak was referred to the Canadian Friends Service Committee, which arranged accommodations for him and his wife, and a short time later he returned to offer his help.

“I had been very involved in what we used to call ‘the movement’ in the US,” he says. “I didn’t come to Canada to hide under a rock.” Meanwhile, Paterak says, Tony Hyde had grown tired of counselling draft resisters and liked the idea of hiring an American to take over the work. But there was suspicion—omnipresent in those days—that Paterak might be a double agent. During his VISTA service, Paterak happened to have worked with legendary civil rights activist Bernard Lafayette, who as a Freedom Rider had earned credibility with beatings and arrests; Lafayette was as good a reference as any activist could hope for. SUPA eventually scraped together enough money for a pricey long-distance call to Chicago to check Paterak’s bona fides, and he soon became their first American draft counsellor in Toronto. His duties consisted primarily of corresponding and meeting with prospective immigrants, and offering informal support to newly landed draft resisters in the form of housing and employment leads and social connections. He also did outreach at Canadian universities and was a frequent media liaison.

In 1967, Paterak was indicted in absentia for draft delinquency. An FBI handler on his case regularly called his mother to check in on his whereabouts. “He was assigned to do things like show up at family funerals in case I’d crossed back into the US,” Paterak explains. In February 1970, the agent called his mother in Massachusetts and informed her that the charges against her son had been dropped. His indictment had been based on actions by the Selective Service board that the US Supreme Court had just deemed illegal in two landmark decisions, Gutknecht vs. United States and Breen vs. Selective Service Board. The high court ruled that the Selective Service System could not accelerate induction based on a would-be conscript’s anti-war activities or his failure to appear for a physical examination, both of which it had done in Paterak’s case. Paterak went to the US Consulate to apply for a passport, reckoning it wouldn’t be issued unless the FBI agent was telling the truth. He also had his father go to Boston for facsimiles of official documents stating plainly that charges had been dropped.

In early May 1970, the week after Ohio National Guardsmen killed four unarmed anti-war demonstrators and permanently paralyzed a fifth at Kent State University, Paterak and his wife crossed the border and left Canada for the first time in almost four years. The highways were full of students hitchhiking, since universities had been let out early in response to widespread protest. To celebrate the dropped charges, the couple went backpacking through Europe. When they returned, they were confronted with the decision of whether to stay in Canada or return to the United States. They chose Canada.

Over the next forty years, Paterak worked for NGOs, ended his first marriage, began a second, had children and became a potter before concluding his working life in municipal politics. “In the end, I love Canada,” he says. “I’m grateful that people took me in when we were basically just collateral damage from the other side of the border.” Looking back, Paterak asserts that he is not “emotionally bitter.” “But I am intellectually bitter,” he says, “that cynical politicians in the US were willing to destroy so many lives.”

By 1968, there would be over five hundred thousand US troops in Vietnam—on average, more than three hundred of them were dying every week, along with about five hundred allied South Vietnamese and perhaps twice as many enemy troops and civilians—and hundreds of thousands of Americans were expressing their moral opposition to the war. Resistance took many forms, each with its own rationale and degree of commitment. For draft-eligible men, the most radical acts of protest involved refusing to cooperate with the conscription system; some went underground within the United States, some went to prison, and some left the country. Canada was the obvious and by far the most common choice for most who chose to expatriate, although a few war resisters went as far as Sweden and Japan. John Hagan reported that half of the resisters he surveyed about their decision to come to Canada found it difficult or extremely difficult; resisters founds themselves under tremendous psychological pressure owing to the stigma associated with their chosen form of civil disobedience.

In February of 1967, Mark Satin, a restless and resolute twenty-year-old from Minnesota, had disembarked from an airplane in Toronto, almost certain he’d never be able to return home. Within two months, he became director of SUPA’s anti-draft program. Resisting the war aligned with the organization's broad spectrum of New-Left concerns. SUPA, however, soon disbanded, and Satin reorganized the draft-counselling operation under the name Toronto Anti-Draft Programme. By October 1967, Satin had conceived, written, and solicited practical essays from American and Canadian contributors for a little book that would become hugely influential: the Manual for Draft-Age Immigrants to Canada. (It was also among the first commercial successes of House of Anansi Press.)

The Manual for Draft-Age Immigrants to Canada initially ran to six editions, totalling sixty-five thousand copies. It was shipped over the border for distribution by draft-counselling and conscientious-objector committees. More than one-third of the war resisters surveyed by Hagan in his research reported having read the Manual before seeking refuge in Canada. Although Hagan calls it “a manifesto for the mobilization of the resistance movement,” Mark Satin insists that he hadn’t intended to proselytize. “I don’t call them refugees,” he says. “I don’t call them exiles. I don’t say that they’re persecuted. I wanted them to come as immigrants. The thing that strikes me the most when I look back at the Manual is toward the end, when I list all the occupations [in demand in Canada]. I say, ‘If you can’t qualify to come up here, take the couple of months to acquire a skill. Become useful to this country.’ I mean, that’s almost Trumpian in its tone!” The book entered the annals of popular culture before the war in Vietnam was over, and has since figured in major novels like John Irving’s A Prayer for Owen Meany and Mordecai Richler’s Barney’s Version, where Barney’s serious-minded nemesis Blair is a draft-dodger who arrives at the Panofskys’ home after finding their address on a list of sympathetic Canadians in the Manual (an actual list included in the Manual, although the fictional Panofskys were obviously not on it).

Most resisters ended up in major cities when they came to Canada, with an estimated twenty thousand living in Toronto by the early 1970s. Many of these lived in the neighbourhoods around the University of Toronto, particularly Baldwin Street, which earned a reputation as the “American Ghetto.” Toronto’s resister community came to be closely identified with local institutions such as Grossman’s Tavern, the experimental Rochdale College, and the Whole Earth Natural Foods Store, which was managed by a resister from California named Michael Ormsby. Large numbers of deserters also ended up in Vancouver, Ottawa, Montreal and Regina. But it’s hard to get a handle on the real number of war resisters in Canada, since some chose anonymity owing to irregularities in their immigration status, while others feared anti-American sentiment among Canadians, and a significant minority eventually returned to the United States.

African-American war resisters were a special case, and relatively little is known about them, though enough of them arrived to justify the founding of the Black Refugee Organization in Toronto in 1970. Unlike middle-class white American resisters who could pass as middle-class white Canadians with minimal effort, African-American resisters came from a cultural background that was completely different from that of Toronto’s small Black population, most of whom were of Caribbean and West Indian descent. E.J. Fletcher, an African-American resister from Cleveland, puts it this way: “The Black man in the States has had such a profound effect on the country that in fact there are many institutions, the music, the foundations of jazz and blues for instance, which are for the most part Black. And so even though the Black man sees all this racism in the States, he can also see his own society, a Black community, his own culture.” Black resisters were thus doubly alienated in Canada—from their country and from their subculture within that country. Eusi Ndugu, a Black resister from Mississippi, said in a 1971 article for Amex, a Toronto magazine published by American war resisters, that moving to Toronto was “like jumping into a pitcher of buttermilk.”

Fran and Tony McQuail took up residence on an old farm in northern Huron County, Ontario, in 1974. An uninsulated barn with chink-riddled walls was the only structure standing, and for a year that’s where they lived. Fran recalls that they would shift their sleeping quarters from one side of the building to the other, depending on the direction of the wind. She is one of tens of thousands of American women who came north to Canada during the late sixties and early seventies, either because they were in dedicated relationships with men fleeing military service or because they disagreed with the Vietnam war and felt that by remaining in the United States they were complicit.

Fran grew up in the small city of Richmond, Indiana. For her, moving to Canada felt no different than a move from town to country within the United States. Even the land resembled her native Indiana. “Many people [in Huron County] were socially conservative,” she says. “We were seen as hippies who wouldn’t survive. When we got married I changed my name so we’d be believed, and we made an effort to invite the neighbours to our wedding out here in the orchard.”

Not all Canadians welcomed the southern influx. In an article for Amex, the poet Robin Mathews argued that draft resisters were agents of US imperialism. “US influence diverts Canadian attention to US problems,” he wrote. “One of the words that offends me most is the import of the word ‘pig’ for policeman. US policemen may be pigs… Canadian policemen are not pigs. You will say, ‘But it is Canadians who use the word.’ I will ask, ‘Where did they learn it?’” According to historian David S. Churchill, “Assimilation, the complete and utter rejection of things American, and the surrender of US cultural capital were thus the only way for the expatriate to avoid reproducing and disseminating US imperialism.”

Fran McQuail made an effort to fit into her chosen community from the day she and Tony arrived, and eventually they found their niche among politically like-minded Canadians. Although she regularly travels to the US to see family, her hometown has come to feel increasingly foreign. After almost forty-five years here, her talk is peppered with rural Canadian speech markers, and she has officially renounced her US citizenship.

Tony McQuail was born in southeastern Pennsylvania in 1952, which puts him in the last wave of Vietnam-era draft resisters. He and Fran were both brought up as Quakers, dedicated to non-violence. Tony was never very receptive to the sixties-era American anti-war movement and its fighting rhetoric. As he sees it, to use the language of war is to engage in violence. “Fighting and war never seemed like a very effective way of addressing problems,” he says. “They just sow the seeds for more war and fighting.” To him, the whole of American society seemed, and still seems, contaminated by militarism.

As religiously motivated pacifists, Quakers were eligible for conscientious-objector status from the start of the Vietnam War. In his early teens, Tony assumed that he would apply for a religious exemption, but at sixteen he began offering draft counselling at his Quaker meeting. The experience led him to view the draft as a corrupt and cynical system that disproportionately affected the poor and less educated, and came to feel that taking an exemption was a form of legally sanctioned cooperation. Non-cooperation—refusal to serve the war effort in any capacity—carried a sentence of between two and five years in prison and a fine of up to $10,000. The more he thought about going to prison, though, the less sense it made, because when he got out he’d have to become a “tax resister” to stay true to his convictions, and even that wouldn’t be enough. “I had to be a non-cooperator with the whole society,” he says, “and the best way to do that is to say goodbye.” He knew from ads in the back pages of the hunting magazines and tax sale registries he read as a teenager that abandoned farmland could be purchased cheaply in Canada. By the time the draft lottery numbers for his birth year were drawn, he had moved north.

Tony arrived in Goderich, Ontario, in 1971 for a job on a farm, carrying with him his settler’s effects: a toolbox, some clothes, two hunting rifles and a shotgun. He was eighteen years old. In the summer of 1972, he hitchhiked across the country, and in 1973, purchased the farm in Huron County, tucked among the rolling hills of the Wawanosh Moraine. Fran, whom he had met at Quaker boarding school, moved up the following year. Meanwhile, he completed single years at the University of Toronto and the University of Guelph before transferring to the University of Waterloo, where he took a bachelor’s degree in environmental studies.

On a scorching day this past summer, Tony leads two horses up a dirt track between the barn where he and Fran spent that first year and the hilltop where their house sits now. Tony is slim, his upper back is permanently bent from work, and grey hair wings out from under his straw hat. He hitches the horses to the worn wooden singletrees of a hay rake and climbs onto an old school-bus seat mounted on the cart. The fields roll down from the tree-studded ridges into a basin, forming a contained geography, a whole country in miniature. When he’s done haying, he hands the horses and rake off to his daughter, and as we walk, he tries to articulate what makes Canada different from the United States. He lands on an old saw: Canada as a cultural mosaic, each tile contributing to the whole, and the US as a melting pot. Even if the outcome often looks similar in both countries, Tony believes there’s at least a difference of sensibility, in the way each nation sees itself. “You know what happens in a melting pot?” he asks. “You get a little steel and a lot of slag. And it’s only the steel that really counts.”

In the summer of 1972, literary critic James Polk published a short essay on the characterization of animals in Canadian fiction, in which he argued that readers are made to identify sympathetically with them as victims of the hunt. Polk contrasted this with an anthropocentric American tradition that pitted the protagonist against wild nature, of which Moby Dick was the archetypal example. “As Canada’s perennial questioning of its own national identity is increasingly coupled with a suspicion that a fanged America lurks in the bushes, poised for the kill,” he concluded, “it is not surprising that Canadian writers should retain their interest in persecution and survival.”

While working on his PhD at Harvard, Polk, an American, had fallen in love with a fellow student named Margaret Atwood, whom he eventually married and followed north. In the acknowledgements to her now-classic, if controversial, Survival: A Thematic Guide to Canadian Literature, Atwood wrote, “I should like to thank… James Polk, who thought first about animal victims.” Survival became, after the Manual for Draft-Age Immigrants to Canada, the second major commercial success of the House of Anansi Press, of which James Polk would later become editorial director.

It’s not hard to imagine why many war-wary American expatriates felt like prey to a predatory US government. Like animals on the run, many war resisters took to the woods when they crossed the border. Mark Frutkin first came to Canada with the idea of emigration somewhere in the back of his mind in the summer of 1970. He had recently graduated from Loyola University in Chicago, and spent a year teaching in a small Catholic school in a Cleveland suburb. When the Kent State shootings made news on May 4, 1970, a teacher at Frutkin’s school opined that the students got what they had coming to them. Frutkin remembers thinking that he didn’t want to live in a place where schoolteachers said things like that.

That summer, he drove around Lake Erie and found a place to sleep in a house on Dundas Street in Toronto where some war resisters had already settled. It was here, he thinks, that he read Mark Satin’s Manual. Later that summer, he drove to Wakefield, Quebec, with some friends and took a temporary job in a restaurant that would become the hub of the area’s backcountry bohemian scene. One day, he took a drive into the bush west of town and discovered an abandoned farm for sale in the northern Gatineau hills. It stuck in his mind like a seed.

In the fall he returned to Ohio for his pre-induction physical. Everyone he knew had told him he would never be drafted, because he was too short and had flat feet. To his surprise, he was judged fit for service. But by the time he received an induction notice, with the help of his older brother and a friend, he’d already gotten title to the farm in the Quebec woods. For nine years he lived in a small cabin there, with no electricity and no running water, alone for long stretches of time. At other times, the farm became an informal commune, but he rarely had contact with other American resisters.

“I’d have come to Canada even without the draft,” Frutkin, now an internationally recognized author, told me last summer. Frutkin’s mother was from Toronto, and growing up, his closest extended family ties had always been north of the border. Summers were often spent visiting relatives in Toronto or at a Georgian Bay cottage. “I had a very strong connection to the Canadian landscape.”

Frutkin’s statement—that he’d have come north one way or the other—is somewhat surprising, given that he sticks draft resistance right in the title of his 2008 memoir about his years on the farm. Erratic North: A Vietnam Draft Resister’s Life in the Canadian Bush bounces back and forth through time and space to tell the story of three draft resisters: his grandfather, Simon Frutkin, who fled Belarus to escape conscription in 1896; Louis Drouin, his Quebec neighbour on the farm, who refused to fight in the Second World War; and his own story of flight from induction and all he believed to be wrong with the United States. But the book is equally about one young man’s quest for a life of simplicity far from the centres of power and commerce. “Armies and protests are all about crowds,” he writes. “Canada, for me, was all about loneliness.” This motivational overlap is one of the reasons it’s so difficult to tease apart the strands of history that weave together to form the story and legacy of American war resisters.

Kathleen Rodgers has studied the intersection of Vietnam-era war resistance and the back-to-the-land movement, with a focus on the West Kootenays in British Columbia, where she found that as many as fourteen thousand draft resisters are thought to have settled. Large numbers of resisters also opted for the simple life on the Gulf Islands, the Sunshine Coast, and in remote corners of Ontario and eastern Canada where land was cheap. These young idealists were as wary of the prospects of sudden revolution, the fading hope of the Marxist left, as they were of American overreach. “The personal lives of the migrants and the community they joined became an embodied critique of the society they had fled,” Rodgers writes. “Going back to the land in Canada provided personal refuge for those young Americans seeking an escape from conventional life trajectories and from the expectation of military service, but it also created ideal conditions for social transformation.” Flight from the US and to the land was a unified gesture.

In Erratic North, Frutkin puts the appeal of the agrarian, survivalist life more poetically: “For us the night out the back door of the cabin was a blank negative photo on which we could project anything—hope, fear, the unknown.”

Fifty years on, the war resisters can be seen as a fringe element of the American resistance to Vietnam policy, winging a wrench into the works of the US Selective Service System; as a reminder to Canadians that the American way is not the only way of living on North American soil; or as the sum of the cultural contributions of individuals—the Literary Review of Canada’s list of the country’s one hundred most important books, for instance, includes two by war resisters and one by Naomi Klein, the daughter of war resisters. But it’s undeniable that draft dodgers helped to shape and reinforce the way Canada has come to see itself over the past fifty years.

Richard Paterak came north shortly before Mark Satin, and the two crossed paths in the early days in Toronto. Speaking about his work counselling fellow resisters, Paterak says, “Mark Satin was good and bad.” He admired Satin’s devotion and energy but says that he could only see things from his perspective as an American. Both Satin and Paterak were portrayed in a 1967 article for the New York Times as cut from the same cloth—whiny youngsters, possible cowards, who’d gotten in over their heads with outrageous left-wing ideas. To listen to the two men today, they instead seem to represent two kinds of American war resister—those who were destined to repatriate after President Carter extended a pardon in 1977, and those who would embrace Canada as their natural home.

It’s tempting to conceive of the war resisters’ migration northward as one of many migrations that give shape to a recognizable Canadian identity—as if there were fundamentally an American way and a Canadian way of being, and each of us could choose between them. (Seeing things this way helps to explain why draft resisters who stuck around often remember a feeling of “coming home” to Canada when they first arrived.) George Fetherling knew what his choice was: “My only ambition now,” he wrote in his memoir of the sixties, “was to be a last-generation American and a first-generation Canadian.” National Post columnist and steadfast war-resister apologist Robert Fulford recalls that, after Jimmy Carter’s amnesty, Baldwin Street in Toronto, once the hub of the American émigré community, “lost its reason for being.” Some, says Fulford, returned home to America; others shed ex-pat status for Canadian identities. Draft-dodger culture was soon absorbed into the process of history as if it had never been.

Richard Paterak has no doubt about the importance of their legacy in the US. “We played a significant role, together with others, in making the war effort politically and practically a dead end,” he says. But Paterak remained in Canada. Mark Satin eventually returned to the United States, where still today he sometimes wonders whether he made the right decision. Back at home, he made a name for himself as a champion of third-way politics; and in anticipation of the fiftieth anniversary of its first printing, a new edition of the Manual for Draft-Age Immigrants was released this past August—a testament to its enduring place in Canadian history.