Photographs by Galen Exo.

Photographs by Galen Exo.

How to Heal

As fatal overdoses skyrocket in BC, Jackie Wong revisits lessons from the province's HIV/AIDS crisis.

It was 1993 and Monty O’Toole was living at the Silver & Avalon, a single-room occupancy hotel on Pender Street just west of Vancouver’s Chinatown. He was in his late thirties and had moved to the west coast after being released from the Kingston Penitentiary, where he’d served time in maximum-security for aggravated assault. He was addicted to cocaine and heroin and would continue to be, on and off, for more than a decade.

O’Toole was born in Ontario; at fourteen, he started living on his own. He started out in New York City and then hitchhiked across the country to Los Angeles at fifteen. He robbed people and hurt people. He was raped in New York City and kidnapped in LA. “Monsters are made, they’re created. They’re not born,” he says. “We’re all born children.” People tell him he’s lived a fascinating, adventurous life, the kind that would make a great book. “It’s been horrific,” he says.

After getting out of Kingston Pen, O’Toole arrived in Vancouver hoping that his new surroundings would offer a fresh start, specifically because he thought drugs wouldn’t be as readily available in Vancouver as they were in Toronto. But by the time he arrived in the city in 1990, the illicit drug market was thriving. Injection cocaine had established itself on the scene in the late eighties, and in the early nineties, a dangerously pure heroin known as China White spread through Vancouver's streets.

“I remember saying, ‘God, if this is life, you can have it. ‘Cause my life sucks,’” O’Toole says. He was on welfare, living on $100 a month, and the fresh start he’d been seeking seemed increasingly out of reach. Drugs helped him cope with his circumstances.

One night while using cocaine at a West End apartment, O’Toole shared a needle with a friend who was HIV-positive. He knew the health risks, but he was feeling so low it didn’t seem to matter. Injection cocaine users in Vancouver at the time rarely had enough needles to go around. BC’s first needle exchange program had opened only four years earlier, and cocaine users customarily walked away with fewer needles than they required; the program had been designed primarily for heroin users and it kept a tight cap on the number of needles distributed to any one person at any given time. People needed to show workers track marks on their skin in order to begin receiving clean needles, and a user could get no more than one needle at a time if they didn’t have any to trade in. Because cocaine has a much shorter half-life than heroin, a cocaine user might require twenty a day, compared to a heroin user’s three or four. All of this left cocaine users particularly vulnerable to risky needle-sharing situations.

A few months after sharing the needle, O’Toole was walking outside the Silver & Avalon. He paused to examine his reflection in a mirrored window. He was wearing a red baseball cap; the movie Philadelphia had just been released in theatres. “Oh fuck,” O’Toole remembers thinking. “I just knew in my soul that I was sick.”

He went to a doctor’s office on Burrard Street, seeking a prescription. While there, he took a blood test and was told to return three weeks later. When he came back, the doctor told him he had tested positive for, among other things, Hepatitis C and HIV. The doctor and his secretary wrapped him in their arms. “The two of them just hugged me,” O’Toole recalls. “And I started weeping.”

O’Toole was one of approximately seven hundred people newly diagnosed with HIV/AIDS in British Columbia in 1994. He was part of the second major surge of HIV/AIDS diagnoses in the province, which heavily affected injection drug users. The first surge, which took place in the 1980s, primarily affected men who had sex with men.

Between 1987 and 1991, HIV/AIDS killed 686 people (671 men and fifteen women) in BC, and 4,189 people across Canada; BC’s rate of HIV/AIDS deaths was 1.39 times the national average. In Vancouver, HIV/AIDS deaths outpaced heart disease, cancer and accidents as the leading cause of premature death among men. The year of O’Toole’s diagnosis marked the height of the crisis: in 1994, an average of five people died of HIV/AIDS and related illnesses every week in BC.

Today, the province is facing another devastating health crisis. Illicit drug overdoses are killing four times more British Columbians than HIV/AIDS did at its height. By the most recent count, 981 people died of illicit drug overdoses in BC in 2016, and a whopping 1,422 died of illicit drug overdoses in 2017 (the BC Coroners Service is still working through investigations backlogged because of the sheer rate of overdose deaths in the province, and these numbers are expected to continue evolving).

The overdose crisis is exacerbated by the presence of the powerful opioid fentanyl on the illicit drug market. Fifty to one hundred times stronger than morphine, fentanyl is used legally in palliative, emergency and surgical settings. But its presence on the illicit drug market means that unknown, potentially lethal quantities of it are cut into cocaine and heroin. “It’s like playing Russian roulette because it’s in everything,” O’Toole says. “I’ve seen a lot of people die.”

At the Dr. Peter Centre, BC’s only day health program (clinical and basic care services offered during daytime hours) and twenty-four-hour nursing residence for people with HIV/AIDS, O’Toole says many members have died due to drug overdoses this year. When we met over breakfast at a Davie Street diner in May, it was during a particularly difficult time of loss at the centre; O’Toole told me that about three people connected to the Dr. Peter Centre were dying each week at the time. O’Toole, who visits the centre every day for meals, to do laundry and to play guitar with friends, says he doesn’t want his own picture to join the dozens posted regularly on the centre’s walls, memorializing people who have died. His life, buoyed with faith and friendships, now feels purposeful. Thanks to a rental subsidy from Vancouver Native Health Society that has supported him for twenty years, he’s living happily in a West End apartment a short walk away from the Dr. Peter Centre. “I could never live like I do now without them,” he says. He hosts two neighbours for coffee in his suite every morning. And on top of that, he’s healthy. To suppress HIV replication, he takes two pills a day of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) medication. It’s a dramatic shift from the many pills he was prescribed in his early days of diagnosis. Like his peers in the nineties, he could feel the medication’s toxicity and suffered through the embarrassing side effects, like explosive diarrhea. He’s also taking a new Hep C treatment. All in all, he’s feeling more physically well than he has in years.

“I should have been dead years ago,” O’Toole says. But instead he’s gaining weight, seeing his face fill out again. “I’m so happy about that,” he says.

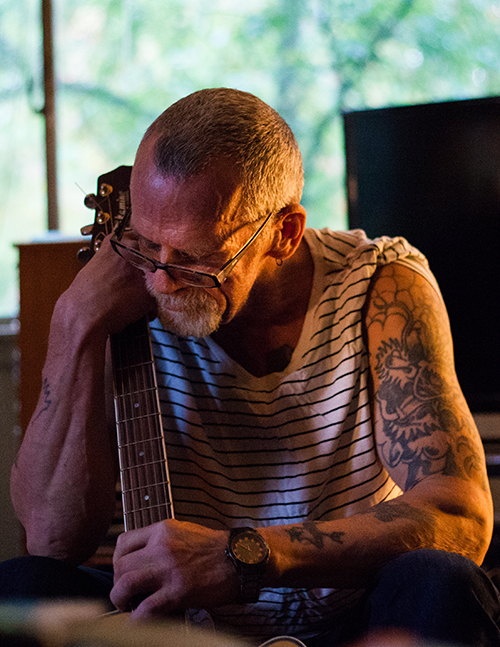

Monty O'Toole plays guitar in his apartment in the West End of Vancouver.

While survival can feel like luck for people like O’Toole, living with HIV/AIDS is grounded in science. Three years after his diagnosis, a watershed medical advancement changed HIV/AIDS treatment dramatically.

In July 1996, Dr. Julio Montaner, a forty-year-old physician, was part of the organizing committee for the International AIDS Conference taking place in Vancouver. The previous December, he’d made a breakthrough in shutting down HIV replication through the exploratory use of a triple-drug cocktail. His findings suggested that starting a three-drug treatment for people newly diagnosed with HIV could improve their health outcomes by dramatically reducing their viral load and, by extension, lowering their risk of disease progression (and, it later turned out, their risk of transmission). What had started as an exploratory measure born of desperate circumstances soon became a new set of antiretroviral therapy guidelines.

At the International AIDS Conference, Dr. Montaner and the international colleagues he’d collaborated with unveiled their findings. The rapid adoption of triple therapy as the new standard of care for HIV infection was, as he remembers, unprecedented. “You can call it a leap of faith, you can call it, ‘we made a gamble,’” Dr. Montaner says. “I don't care what people call it. At that time we felt like... standard operating procedures may not be applicable when you are facing a crisis.” Within months, death rates from new and ongoing cases of HIV/AIDS began to decrease.

Miranda Compton, who worked for AIDS Vancouver from the early 1990s into the mid-2000s (first as an intake worker, and then, eventually, as a director and supervisor), remembers the remarkable changes brought about by the advent of triple therapy in 1996. “Really, almost overnight, it stopped people from dying and progressing to advanced AIDS,” she says. This marked a startling contrast from Compton’s early years at AIDS Vancouver. “When I had started, there were about twenty people dying a month, just from our client base, just here in Vancouver,” she says. “The treatment developments changed that completely.” For O’Toole and his peers, these advancements meant that they would survive an illness that they’d first expected to die from.

Today, Compton is the director of prevention for Vancouver Coastal Health, where she implements the health authority’s response to the overdose crisis. Dealing with today’s overdose crisis can sometimes feel like a familiar struggle, echoing the HIV/AIDS crisis of the 1990s. Then and now, Compton says, stigma and criminalization of people with HIV/AIDS and with drug addictions present ongoing barriers to connecting people with support and mobilizing scientists to advance treatment innovations.

“The stigma around HIV has been remarkably enduring,” she says. If a person discloses to their coworkers that they’re living with HIV, they may not receive the same support as a person who casually mentions they have diabetes or another chronic health condition.

Similarly, stigma around addiction and drug use is “a huge impediment to us moving forward with really comprehensive treatment and support for people who are living with substance use issues,” Compton says. “And the criminalization of drug use is also a major contributing factor to us being able to really have a comprehensive and supportive response.”

To Compton and others, providing meaningful supports for people using drugs in the overdose crisis requires a multi-faceted approach. That includes working towards change in drug policy, so it no longer forces people to purchase drugs from a contaminated supply, as well as improving access to prescription injection opioids for those who need them. Currently, such prescriptions are only available to a select number of people in the Downtown Eastside following years of Vancouver-specific clinical trials. No one else in North America has access to this treatment. Widespread access to suboxone and methadone, two medications that treat opioid addiction by reducing withdrawal symptoms, must also be made a priority.

Such policy changes would shift the focus from a drug user’s criminality to their health, which lies at the heart of harm-reduction approaches to substance use. Harm reduction approaches are often shaped and stewarded by community and frontline responders, like the Downtown Eastside community members who established grassroots overdose prevention sites in the neighbourhood during the fall of 2016, when record numbers of people were dying of overdoses and the community saw a need for more safe spaces for people to use drugs and avoid overdosing alone. Thanks to a strong tradition of drug user activism in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside, the neighbourhood is now home to progressive landmarks like Insite—the first legally sanctioned supervised-injection facility in North America, founded in 2003—and a range of needle exchange programs and overdose prevention sites operated by drug users. Years of drug user advocacy have eliminated the restrictions needle exchange programs carried in the early nineties, making them more responsive to the needs of a range of drug users, including cocaine users. While the healthcare community has credited user-run needle exchanges and places like Insite for saving lives and improving public health, neither are commonplace anywhere else in the country or continent. It was only last winter that the federal government started approving prospective supervised-injection sites in other major cities across Canada. No such sites exist in the United States, where needle exchange programs are relatively few in number and largely the domain of drug user advocacy groups, rather than governmental health agencies.

Today, Compton says the biggest challenge lies in connecting with people they’re not currently reaching, such as the majority of people who die of overdoses in private residences. That’s “another parallel with the AIDS epidemic,” she says, when there was also a robust community response in Vancouver’s inner city, but fewer resources and community connections for people in outlying areas.

For his part, Dr. Montaner is frustrated that the overdose crisis has not met the same rapid intervention that turned the tide on AIDS in the nineties. “The ability to move the implementation of best available evidence forward has not been quite as effective today as it was at the peak of the AIDS pandemic,” he says. “This is despite the fact that we have a higher level of evidence in support of novel interventions—for example, supervised consumption sites; low-threshold, on-demand detox and addiction services; injectable opioid substitution—than we had back then for the implementation of triple drug therapy.” Simply put, we need to learn why HIV/AIDS advancements were so effective in the mid-nineties in order to curb the current fentanyl crisis.

Compton credits strong activist response from people living with HIV/AIDS in the 1990s for the speed and impact of medical advancements for HIV/AIDS treatments. Communities of affected people mobilized, winning over scientists, and lawmakers responded to this pressure, she says. With today’s overdose crisis, to Compton, the solutions—such as prescription opioids for people with severe addiction, or decriminalization, legalization and regulation—seem frustratingly near at hand, yet remain unimplemented on a large scale. “These are all things that are within our reach, if we can get through the policy barriers,” she says.

But legal policy isn’t the only thing standing in the way of solutions to the overdose crisis. There’s a gap between acknowledging the solutions that exist and the social pressure that would spur their implementation. The public face of HIV/AIDS in the 1990s consisted of people from many walks of life, notably public intellectuals, artists and white professional men whose access to social networks with money and media connections lent the movement mainstream credibility. The late Dr. Peter Jepson-Young, for whom Vancouver’s beloved Dr. Peter Centre is named, was diagnosed with HIV/AIDS shortly after completing his training to become a medical doctor. When he became too ill to practice medicine, he recorded 111 video episodes chronicling his experiences with HIV/AIDS that CBC television broadcast nationally over two years. He died in 1992 at the age of thirty-five. By then, he had survived an AIDS diagnosis longer than any other individual in BC, and his public influence had ripple effects in both the HIV/AIDS community and Vancouver at large. A documentary about his life titled The Broadcast Tapes of Dr. Peter was nominated for an Oscar in 1994, and the Dr. Peter AIDS Foundation opened what is now known as the Dr. Peter Centre three years later. Jepson-Young’s parents continue to be active public ambassadors of the Dr. Peter Centre and their son’s legacy.

Today, for users who do have some measure of privilege, the crisis is happening primarily behind closed doors. And the stigma that dogs users of injection drugs is compounded for street-level users living in poverty, who face intersecting barriers, such as family trauma, mental illness and abuse. In BC, the First Nations Health Authority issued a report this summer that showed Indigenous people are five times more likely to experience an overdose than non-Indigenous people; moreover, when Indigenous people experience an overdose, they are three times more likely to die from it than non-Indigenous people. Not coincidentally, Indigenous people are over-represented among Canadians living in poverty. While influential drug user advocacy groups such as the Vancouver Area Network of Drug Users (VANDU), consisting of both Indigenous and non-Indigenous people, are active in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside, they lack connections to upper-middle-class resources that could otherwise secure them a spot in the mainstream public consciousness and, by extension, mount the social pressure that could lead to faster policy and medical interventions.

No major change to drug policy will work without comprehensive supports that address the social determinants of health in addition to the physical ones. “We absolutely have to address the structural issues like housing and income disparity and the things that are keeping people from accessing medical care, keeping people from seeing a reason to stay with us and to stay alive,” says Mary Petty, a frequent adjunct faculty member at the UBC School of Social Work with a long history of community organizing as well as frontline, clinical and social work during the HIV/AIDS epidemic.

Compton agrees. “It’s not simply ‘Just take this pill, get your methadone, get your suboxone.’ We really need to wrap that system of supportive care around individuals in order for them to be successful,” she says. “And I don’t think we’re quite there yet.”

“I just put one step in front of the other,” says George Astakeesic, a fifty-four-year-old who was born into an isolated reserve community in Manitoba. He lives in subsidized housing for people with HIV/AIDS in downtown Vancouver. He was diagnosed in 1990, in his late twenties, during a period where he was using injection cocaine and doing sex work to get by. “I was living in East Van,” he says. “There was a group of us that were living together. We used to run a house where we dealt out of. That’s where I started using. Coke first, and then heroin came later.”

In the early days of his diagnosis, he was prescribed zidovudine, better known as AZT. The drug, used to delay the development of AIDS, was newly on the prescription drug market at the time. But the side effects were so intense that Astakeesic stopped taking it within a month. “It was so toxic,” he remembers. “I was just smelling it, tasting the toxicity of the medication and realized it just wasn’t for me. I thought, well, if I can have five years of quality life, I’ll take that over having ten years of terrible life.”

Astakeesic was prescribed different combinations of drugs before he found one that worked for him. The current combination requires him to take one pill a day, and comes with very few side effects. While his physical health is stable, Astakeesic says his mental health is “up and down.” He takes benzodiazepines and anti-depressants for bipolar disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder; his mental health had been a longstanding struggle for years before he started using intravenous drugs.

Astakeesic describes the community where he grew up as a place that “was very discriminatory” against people who were gay. “No one ever came out in those days,” he says. He’d known he was gay since childhood, and even then, he felt there was no way out but to end his own life. “I started experimenting with alcohol and stuff like that when I was quite young,” he says. He began to attempt to overdose around age ten.

He had few people to turn to for support. His mother, a residential school survivor and survivor of severe abuse, had Astakeesic when she was a teenager. He was adopted into a foster family, and his adoptive parents were in their sixties. “They had a hard life,” Astakeesic says. “They were illiterate.” When he was ten, the same year he began contemplating taking his own life, his foster father killed himself. That year, Astakeesic says, his childhood ended.

His foster father would not be the only such loss. “My little brother committed suicide and my grandfather committed suicide and my cousin committed suicide,” he says. “It’s generational.” His foster mother, mired in grief, passed away two years after her husband.

Astakeesic moved to Vancouver in his mid-twenties and, four years later, fell in love with a man named Richard just before he turned thirty. “He was a good, stabilizing force for me,” Astakeesic remembers. Their relationship ended tragically in 2003, after ten happy years together, when Richard died at home of what Astakeesic later pieced together was likely a methadone overdose. “I found him in the morning,” Astakeesic recalls. “I had no idea he was using methadone.”

The impact of losing Richard was—and still is—devastating. Astakeesic gave up his apartment and sold all their belongings because he couldn’t cope with daily reminders of his lost partner. For a time, he ended up homeless.

These days, he tries to keep busy with volunteer activities, and, until recently, part-time work for employers who were empathetic of his mental health needs. But the hardest moments for him come in the night, when he feels lonely and isolated. “My coping skills aren’t that good,” Astakeesic admits. “So I turn to my drug use. Just enough to medicate myself.”

Astakeesic supports harm reduction measures to address addiction, and also calls for less judgment and more empathy for drug users from the general public. “There’s a reason they’re using,” he says. “Sometimes we don’t see it, or they don’t tell us, but there’s a good reason.”

Astakeesic’s struggles illustrate why Andrew Saunderson, a social worker in the Lower Mainland whose clients are living with HIV/AIDS, begins his new client intake assessments by asking them what they need to thrive emotionally and socially beyond the physical facts of surviving an illness. The first conversations Saunderson has with a client are about what brings them happiness, what brings them meaning in life and what barriers stand in the way of that happiness and meaning. “Oftentimes, part of that includes significant counselling and resources related to past traumas,” he says. “Oftentimes, that’s simply connecting people with sufficient transportation or financial resources to be able to access the things that actually bring meaning to why we’re helping keep them alive.”

In Saunderson’s view, it will take the general public a long time to move from judgment to the acceptance that Astakeesic is calling for. He remembers when there was relatively little public interest or empathy towards people living with HIV in the 1990s, until it started infecting babies and hemophiliacs. Similarly, media attention and the public conversation about BC’s overdose crisis escalated only when overdoses started claiming the lives of recreational users, teenagers and people living in the suburbs. “It creates this hierarchy of humanness,” he says. When it comes to treatment, Saunderson believes we are now where the HIV/AIDS crisis was in the early 1990s, before the triple therapy advancements meant new possibilities for survival. He’s eager to advance the conversation from preventing deaths and providing primary health care to a more holistic approach that would more comprehensively address the intersecting social, emotional, relational and economic determinants of people’s health.

“It’s one thing for us to be able to provide you with primary care, which is so necessary, for us to be able to ensure your adherence [to meds], and to even support you with your substance use goals,” he says. “But at the end of the day, if you’re not happy with that process, or if you’re not achieving any sort of meaningful attachment in your life, what are we doing here?”

These are questions that Astakeesic and people like him continue to struggle with. While Astakeesic lives in a central part of Vancouver, in close proximity to community hubs for people with HIV/AIDS, resources in the suburbs and in less-central areas of the city are harder to come by. Unaffordable housing and a tight rental market are forcing already vulnerable people away from the areas where they’re best able to access both the primary health resources and the social resources necessary to cope and thrive.

To Saunderson, the next step in dealing with the overdose crisis, beyond just daily survival, must consist of addressing the complex emotional relationships that people have with illicit drugs, where he sees another significant parallel to HIV/AIDS. “With a new [HIV/AIDS] diagnosis, we grieve significant things… We grieve this ability to not ever take medications to now having to take them every day. We grieve the stigma and the weight that’s now going to come with us and the ability for us to have sexual relations as easily as before,” he says.

“Grief looks really really ugly and complex and kind of goes up and down,” Saunderson says. “But they can go on that journey to the point where [though] the trauma doesn’t go away, the HIV diagnosis doesn’t go away, even their substance use doesn’t necessarily go away, their ability to be able to feel and honour their emotions—and then let them go once they’ve lost their utility—is incredibly empowering.”

Today, BC has among the lowest rates of HIV in Canada. Earlier this year, research from the BC Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS showed that harm reduction and access to HIV antiretroviral therapy averted 3,204 HIV cases between 1996 and 2013. The Lancet HIV medical journal has since published that research, which lies at the heart of Dr. Julio Montaner’s trademark strategy, Treatment as Prevention. “If you have a strategy like Treatment as Prevention that decreases the morbidity and mortality and therefore the infectiousness of that condition, then it will decrease incidence [of HIV/AIDS],” Dr. Montaner says. “And when you decrease prevalence and secondarily decrease incidence, you get maximal impact on healthcare sustainability.” Treatment as Prevention, while developed for HIV/AIDS, has since been applied successfully to other infectious diseases, and even “socially contagious” phenomena like diet and addiction.

The BC Centre for Excellence has deployed the Treatment as Prevention strategy as part of an ambitious global “90-90-90” goal: a 90 percent decrease in AIDS deaths and new infections by 2030, achieved by connecting at least 90 percent of all people in a given healthcare jurisdiction with diagnosis and treatment, and thus, viral suppression. The United Nations is leading the campaign to meet this target.

These goals and strategies have real impact on the lives of people like Sherri Johnstone, who received her diagnosis in 1997. It was the first day of fall, she remembers, seven years after she started using injection cocaine. She was thirty-one and had inadvertently used an infected needle. “I wailed like a baby,” she says.

Johnstone survived those first rocky years of medication alongside so much else. She lived through the heartbreak of giving up her eighteen-month-old daughter for adoption when she moved from Toronto to Vancouver at twenty-three to be with her partner, who then abandoned her. She was a sex worker in the Downtown Eastside during the terrifying years that serial killer Robert William Pickton preyed on women working the streets in that neighbourhood; she decided to leave sex work after surviving a date with a man who hit her, punched her in the back of the head, and then tried to strangle her with her bra.

While her HIV medication has kept her alive, her life wouldn’t have moved forward as it has without non-medical interventions—the kind of interventions that give people like her the ability to build hope for the future. “I think the biggest thing [for me] was having something to love,” she says, “When I got my cat, it gave me something to love and something that loved me back.” The affection of a cuddly companion can seem small, but its presence in a life can be transformative in addressing what medicine can’t. Johnstone’s cat, Echo, now forms the heart of a chosen family that Johnstone prides herself on having built from scratch.

Monty O’Toole and George Astakeesic have, similarly, formed meaningful connections that ground their lives. Monty O’Toole finds peace these days in taking care of his best friend, who survived a stroke two years ago and lives downstairs from O’Toole’s apartment in Vancouver’s West End; George Astakeesic volunteers every Tuesday morning at the Dr. Peter Centre, where he has been a member for fifteen years.

“People living with HIV are often disproportionately affected by ongoing mental health issues, violence, addiction, poverty, homelessness,” says Neil Self, the chair of Positive Living BC. “We often look at a mental health condition or an addiction condition or an HIV condition as sort of separate but manageable. But that’s not really the case. They’re all intertwined and you have to do a holistic look at dealing with them.”

The thing we should keep in mind, says Mary Petty of the UBC School of Social Work, is that the people who are directly affected by the overdose crisis best know their own needs. Medical interventions, however helpful and ultimately lifesaving, can’t stand alone. “You have to have a supportive and appropriate structure to get those to people,” she urges. “And it’s the people, the patients themselves, the clients, the people affected who are able to guide that.”

The principles of Dr. Montaner’s Treatment as Prevention strategy can be applied to treating addiction and curbing the spread of HIV/AIDS through injection drug use. The strategy informed the establishment of Vancouver’s new British Columbia Centre on Substance Use, which opened earlier this year and builds on the efforts of the BC Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS by developing, implementing and evaluating evidence-based approaches to substance use and addiction. Harm reduction lies at the heart of its work, and providing harm reduction alongside expanded HIV/AIDS treatment and prevention will be crucial in addressing both AIDS and the overdose crisis.

“If we are to get to the end of AIDS by 2030, as established in the UNAIDS 90-90-90 Target, we must broadly and universally implement harm reduction hand-in-hand with Treatment as Prevention,” Dr. Montaner recently asserted in a British Columbia Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS press release. “We know these interventions are mutually supportive and essential to reaching people who inject drugs.”

Vancouver continues to lead North America in its harm reduction programs, born of a robust culture of inner-city drug user advocacy and volunteer-led community organizing and activism. It’s the site of the first injectable opioid therapy programs on the continent, where people previously entrenched in addiction receive daily doses of injectable opioids alongside social and medical supports through Providence Health Care’s Crosstown Clinic and the medical team of the PHS Community Services Society, both based in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside. These programs have brought about dramatic improvements in the lives of people who use injectable drugs, and they have demonstrated the positive impact of providing a clean supply of drugs outside the illicit market. Government officials have also acted in response to the overdose crisis. This fall, BC’s new provincial government set aside $322 million to address BC’s overdose crisis through harm reduction, outreach and help for people on the front lines and those most at risk of overdose.

During a visit to Vancouver in September of this year, the national drug coordinator of Portugal, Dr. João Goulão, told the Georgia Straight that while decriminalization is no silver-bullet solution to all substance use and drug policy issues, “decriminalization is important because drug users will no longer fear approaching [health care responders].” In Portugal, the personal possession of illegal drugs has been decriminalized since 2001. That step, in combination with significant new investments in treatment, resulted in a marked decrease in the number of young people using drugs, the number of adults using drugs problematically, and the number of people injecting drugs. Canada’s fentanyl crisis, Dr. Goulão continued, should be declared a national health emergency. “It’s a very, very important problem of public health. And so you have to deal with it in a brave way.”

International evidence shows that both medical and structural alternatives—those that comprehensively and holistically support people who use drugs, and create demonstrable positive public health impacts—would mitigate our current situation, where an overdose epidemic fuelled by a contaminated illicit drug market continues to sweep North America. Empowering those affected to access harm reduction services, build community, and use their voices to advocate for each other can reduce the impacts of both drug use and HIV/AIDS, but only if we, as a society, combat the stigma that keeps those voices from being taken seriously. “So many people have died, and still, there’s not a solution,” Sherri Johnstone says. “If it was ‘normal’ people, this would not be happening.”