Awkward Cause

It’s hard to live low-carbon, especially when you feel like you’re the only one. Kate Black meets a Calgary misfit who keeps trying to fit in.

I can see Nestar Russell for nearly a minute before his Wi-Fi cuts out. He carries his laptop onto his couch and wraps a blanket around his shoulders as we begin talking on Skype.

It’s February. On his side of the screen, in Calgary, it’s minus 18 degrees and snowing. I assume he must keep his heat turned way down. It would fit what I already know about him: that he hasn’t been in an airplane since 2006, that he doesn’t take elevators and climbs nine flights of stairs to his office at the University of Calgary several times a day. He’s vegan, though that part should have been obvious already.

“I feel like I could be doing more,” he says self-deprecatingly. He has a quiet and dry sense of humour—the kind that’s probably necessary for survival when you’re acutely aware of the world’s inevitable heat death—but he’s dead serious when he says this. Then both our screens go black and we can only hear each other’s voices. He can’t see me smiling at what he’s just said: that he doesn’t think he’s doing enough. I’m vegan, too, but I have yet to meet others like me on my side of the screen in Vancouver, let alone somebody devoted enough to reducing his carbon footprint to only travel by bike, bus and train.

I’m disappointed that the screen went black. It’s a real journalism faux-pas to write a whole article about someone without seeing them in the flesh. But it didn’t make sense to fly to meet someone for a story about avoiding planes, so I figured Skype was the next best thing. But now I can’t see his face. Shit.

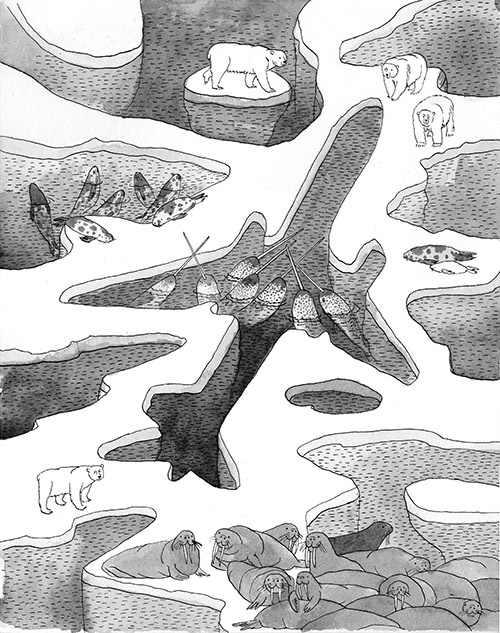

In 2006, Russell was a thirty-six-year-old vegetarian living in New Zealand when he read an article suggesting green-minded voters shouldn’t be taken seriously—because they still fly on planes, all talk and no action. Travelling by plane, Russell learned, is the most environmentally taxing way to travel, partly because of how much fuel planes use, partly because of how high they emit fumes into the atmosphere. About three square meters—a queen-sized bed—of Arctic sea ice vanish for each person on a non-stop flight between New York and London. The same day, he decided he would never fly again.

With his school, work and family all in New Zealand, holding up the no-flying commitment didn’t become a problem until 2011. Russell received a scholarship to study at Nipissing University in North Bay, ON. On one hand, he couldn’t justify the environmental toll of flying halfway around the planet. On the other, he was already struggling to find a good job in his field in New Zealand.

After a bit of research, he learned he could cross the Pacific Ocean as a passenger on a cargo ship. It was a lot more expensive than travelling by plane, but it would work. One of his grad-school friends warned him to look out for seamen—that they’d throw him overboard if he crossed them.

Behind the black screen, Russell tells me about boarding the ship in Auckland. The ship’s crew were nearly all from the Philippines and he was the first passenger they’d had in six months; most were standoffish for the first few days, but eventually they warmed up to him. A couple days into the trip, one of the stewards came up to him. “Do you sing karaoke?”

It was a crew member’s birthday and they were having a party that night. The steward told Russell they wanted him to sing for them. They’d buy him beer. Oh no no no no. A wave of dread washed over him—he needed to find a plausible way out.

The sea got rough that night: thank god. Russell told the crew he was getting sick and would stay in for the night. But the next morning, the steward asked him if he was feeling better. When he said yes, a wide grin stretched across the steward’s face. It’s a ship tradition to have a second party if your birthday falls as you’re crossing the International Date Line, and they were crossing it now. “We’re doing karaoke again tonight,” the steward said. Russell, with no way out, ended up singing in front of sixteen people. “I was terrible,” he says with a laugh.

In the end, Russell didn’t regret a single thing about taking the ship. Sure, vegan options were limited, but it was nowhere near as harrowing as his friend had warned. “Most people couldn’t remember their last plane trip in much detail, but this ship journey is something I’ll never forget,” he says.

Still, it took seventeen days to cross the Pacific. They docked in Panama, then Russell departed via bus and train for the eastern tip of Ontario, a trip he turned into a month-long voyage with stops in various cities. It may have been memorable, but it was inconvenient enough that he’s only done one other ship journey since.

That’s the main reason travelling by sea is better for the environment, he says: it takes so long that he hardly travels at all anymore.

Russell sees these restrictions more like rules than experiments or even sacrifices. They just are. Where most of us might blithely ditch meat or bike to work for, like, a week, to spice up the monotony of our lives, Russell’s commitments become permanent parts of him, like organs. His rules are unmovable. He stretches the rest of his life to fit around them.

In fact, by the time he reached Ontario, Russell had already made a new rule for himself: no elevators. Soon after, he met up with his cohort of other scholarship recipients in Ottawa. The program put him up in a hotel room on the fifteenth floor and he couldn’t get into the stairwell without staff access. He had to ask the front desk to let him take the stairs up to his room.

“Do you have a phobia or something?” the concierge asked.

“Yes,” Russell lied—he didn’t want to make things weird. So the hotel sent an unimpressed chaperone to escort him up fifteen breathless flights of stairs. It was awkward, sure, but not as bad as it would’ve felt to ditch his own standards. That night he went out for dinner, and when he came back, there wasn’t any staff around to let him into the stairwell. He gravely debated his options: sleeping in the lobby or taking the elevator. He caved.

Soon after, at Nipissing, he met the woman he would eventually marry. The tricky part: she wasn’t quite as dedicated to living low-carbon as he was, like their friends and everyone else around him. And, as he would learn later, she wanted to have a baby—a wish of his own, but one he’d mostly ignored. “It’s about the worst thing you could do, carbon-wise,” he says.

In fact, one of the main things Russell realized over the years is that his rules don’t affect just him. It was adding other people into the mix that made low-carbon life real.

Bleak headlines from the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5 °C have been tweeted ad nauseam since October: “UN Says Climate Genocide Coming. But It’s Worse Than That” or “What’s Another Way to Say ‘We’re Fucked’?”

Things are bad. The planet is 1 degree Celsius hotter than it was before the Industrial Revolution. We’re on track to hit 1.5 degrees in twelve years and 3 degrees within the next century if we continue at the current rate, the impacts of which will be devastating: mass drought, destruction of coastal communities and a profound loss of life-sustaining plants and animals, to name the most obvious.

Several news outlets and well-intentioned bloggers responded to the depressing onslaught by publishing steps normal people can take to reduce their carbon footprint, like taking public transit or eating less meat. People on the internet didn’t like this either, and with reason. The individual steps, no matter how drastic, seem impossibly small when compared to the toll taken by massive corporations. Two leading climate research institutes report that 70 percent of industrial greenhouse gas emissions created since 1988 can be traced back to no more than one hundred fossil fuel companies.

This gave rise to a new, cynical debate: whether individual actions matter at all. And if so, why, exactly? A growing body of research is asking the same question. In 2017, for example, Seth Wynes, a PhD candidate in the University of British Columbia’s geography department, was the lead author on a paper that identified the four most effective changes individuals can make to reduce their carbon footprint. Those were, the study found, having one fewer child, not driving a car, avoiding airplane travel and eating a plant-based diet (dairy and meat, especially beef, create almost 15 percent of the world’s greenhouse gases—about the same amount as cars, trucks, airplanes and ships combined).

But the paper also found that textbooks and other educational materials overwhelmingly focused on easier, smaller things: buying organic, hanging clothes to dry, switching plastic bags for canvas totes. In reality, these don’t do much to dampen climate change. Organic produce doesn’t necessarily have a lower footprint than conventional agriculture, for example. Even more depressingly, 90 percent of plastic recycling ends up in the landfill.

Most people do seem to want to do something about the environment. A 2015 report found that 73 percent of millennials are willing to spend more on a brand if it’s “sustainable,” whatever that means. It’s no surprise that every company seems to be greenwashing itself—trying to look carbon-conscious without actually doing anything meaningful, like how Starbucks is phasing out newly unpopular plastic straws with sippy-cup lids that use even more plastic than the straws they replace.

Of course, the planet doesn’t have time for ineffective, small changes anymore, let alone corporate greenwashing. “It’s becoming clear that we don’t have the luxury of slowly wading into the shallow end,” Wynes says. He is also wary of what he calls “techno-optimism,” the idea that new inventions like electric cars and planes are going to “bail us out.” It could be years before an electric plane is efficient enough to make long flights.

Researchers like him want to know why some people do nothing, others do small things and others, like Russell, seem to be doing everything in their power to make a difference. His research is beginning to show that those who take baby steps, who only do things like carry a reusable shopping bag, don’t tend to let these steps snowball into real carbon reductions. Bigger commitments, he’s found, are actually more lasting. Giving up your car is more life-altering than occasionally line-drying your laundry, for example. It’s not just a lifestyle change but a change in your identity, in how you see yourself; other big steps begin to fit more seamlessly into your new self-image.

But that doesn’t explain the answer to the big question: why do some people join that last group to begin with—what makes a person decide to commit? And, after that, what do you have to give up—friends? money? pleasure?—to make it work? Most of us, after all, may care, but we don’t want to go off the grid to show it; we want to be, by all other definitions, a normal person working a normal job and paying rent.

Russell makes it sound simple. “It’s not that weird. I ride a bike everywhere and eat a vegan diet and I don’t fly,” he tells me.

He does still ride in cars, although recently he’s limited himself to three trips per month. He grows some vegetables but laments that he could be growing more. (A reminder: he lives in Calgary, which for now, at least, has snow on the ground more than half the year.) He doesn’t shop often, and when he does, he buys second-hand.

He brings his own containers to takeout restaurants, even if it annoys the staff. He admits it feels odd, bumbling in with his Tupperware that doesn’t fit the restaurant’s proportions. But he tells himself that getting over that mild embarrassment is just part of his life now. “You really do have to stop caring what people think,” he says—though it’s easier in theory than practice.

Yes, at face value, what Russell’s doing doesn’t sound that odd, nor truly embarrassing. But that doesn’t mean he hasn’t gotten himself into situations that are, by many plane-travelling omnivores’ standards, weird. His self-imposed rules got more daunting when he was diagnosed with cancer in 2014. He was in North Bay, still riding his bike—to and from chemotherapy appointments along a “mostly flat” road.

One day after chemo (yeah, that chemo: the one that leaves most people bedridden with nausea and bone pain) he diverted from his regular route to return some library books. Biking up an incline, his heart started fluttering wildly and he needed to rest for a few minutes before realizing he wasn’t dying. Later, when he was discharged from surgery, unable to bear the thought of using the elevator, he snuck down the stairwell with fresh sutures blooming in his abdomen. But his biggest letdown came after nearly dying of sepsis after another surgery. He was down thirty pounds from his already lean and tall 160. The small hospital in North Bay only had meal supplements made with fish, and he decided to put his health before veganism this time. He tells me these stories with a laugh—he’s currently cancer-free.

Other compromises have come up since. Russell and his wife now live in Calgary, where he’s a sociology instructor (his area has nothing to do with climate change; he studies explanations of what caused the Holocaust). But he’s painfully aware he lives in what he calls an “oil town,” with no exaggeration. It’s home to all of Canada’s major oil and gas companies’ head offices. The insignias of energy companies—Suncor, Enbridge, Husky—dapple downtown buildings like billboards in Times Square. Plus, Alberta just elected a government led by a United Conservative Party majority. The party’s leader, Jason Kenney, literally drove into his election-night party in a pickup truck and committed to funnelling $30 million into a provincial “war room” to combat growing disinterest around fossil fuels.

Russell doesn’t have tenure and is only a permanent resident in Canada, not a citizen, so he’s cautious of attending protests. He already takes a professional hit by not travelling. He doesn’t go to swanky international conferences to promote his research. He has organized just as many conferences as he has attended, which is bizarre for a contract instructor.

In fact, many of his colleagues probably don’t even know he lives this way. Russell has been working at the university since 2016 and hasn’t taken the elevator there at all, although his office is on the ninth floor. When his colleagues ask him why, he brushes it off by saying that it’s good for his health. “I spin it in a way that doesn’t have anything to do with climate change,” he says. “I’m not going to be like ‘yeah, I’m really concerned about climate catastrophe.’” He worries about seeming preachy, even with this statement of facts about his own life. He says something he’s already repeated a couple of times: he doesn’t want to be weird.

Of course, Russell is weird, whether he likes it or not. He isn’t loud about his politics, but in car-dense, beef-loving Calgary, he sticks out. In any city, he’d stick out. His wife recently turned down a lunch they were invited to because she didn’t want to make it awkward by finding a place with vegan options. One of their friends calls it “brocc-blocking.”

It’s not that Russell doesn’t see the occasional stares; he just prefers to live with them. “We’re entering an extinction phase,” he says. “I try to keep reminding myself I’m not the weirdo. Getting on a plane to the other side of the continent to go to a rock concert or hockey game, that should be the weird thing.”

Knowing that greenwashing isn’t the answer, researchers are mining behavioural science to figure out how to make real carbon reduction more appealing to adopt. A February report from the UN Environment Programme suggests airlines and restaurants could make their default meals vegan and require people who want to add meat to “opt in.” It gives the example of a Swedish university that cut paper use by 15 percent by switching its printers’ default settings to double-sided.

Does Russell think this is progress? He keeps his politics so quiet, you wouldn’t know the answer unless you asked him directly. But Russell tells me the very idea of needing to be convinced to give a shit confounds him. He becomes more impassioned and less apologetic the longer we speak, and it has a lot to do with talking about the dilemma that has occupied the last few years of his life: whether to have a child. Having kids was never part of his plan—until he met his wife.

Russell has always liked kids, even wanted one himself, but the idea made him worry even more about forest fires. Will babies born today get asthma? What will Spain or California or Australia look like when they’re older—will they be deserts? Will the next generation vilify their parents for not doing enough while they could? Russell wonders what future generations will think about what he calls our “addiction to convenience.” I can’t see his face, so I can only gauge his mood by his voice, a slowly clenching fist. “People aren’t changing, because they can act without impunity. They know when shit hits the fan, they’ll be dead.”

He wonders aloud if people can really say they love their grandchildren if they “aren’t willing to do any more than furiously contribute to the problem.” He exhales sharply and collects himself. “I’m sorry. I feel like I’m getting on my high horse here.”

I don’t mind, though. I agree with what he’s saying and I feel the sickly, familiar swirl of guilt and jealousy in my gut. I wish I could be as bold as him. I’m terrified too, but I still fly in a plane home to Edmonton at least twice each year. I can’t imagine only seeing my parents, my friends, my eventual nieces and nephews through a laptop screen, the way I’m talking to Russell right now. I just ordered a pair of boots—leather-free—from the UK. I’m a hypocrite: I wasted the carbon saved from not raising a cow by having the boots flown halfway across the world.

“The voice inside my head is highly critical of other people’s lives,” Russell says. “But in reality, I’m kind of a people-pleaser.”

In speaking to him, I see that’s true. He’s obsessed with not being self-aggrandizing or aggressive or too political. He doesn’t want to be a social outcast. More than once, he asks me to please interview someone who’s doing more for the planet than he is, though I don’t know any.

Seth Wynes, the researcher, says this is the key thing missing in discussions about individual carbon reductions. Of course, the first step is believing these solitary choices matter. When looking at a cheap flight deal, it’s hard not to feel like the plane’s going to take off without us—and take that queen-bed-sized chunk of sea ice with each person—whether we buy the ticket or not.

For the record, not getting on the airplane does mean something. For starters, each person on the plane adds an amount—a super-small amount, but an amount nonetheless—of weight that requires the plane to burn more fuel. What’s even more important, Wynes says, is how, “When you’re purchasing an airline ticket, you’re saying… ‘Please build more runways so planes can take off. Please schedule more flights.’”

So yes, fossil fuel companies are responsible for extracting the resources. But ultimately, it’s the things people do with that energy—driving cars, flying airplanes—that create the biggest problems. Conversely, individual actions have a wide, yet slow, positive ripple effect, too. Consider the consumer demands of the 600 percent increase in Americans identifying as vegan, for example, between 2014 and 2017.

But people tend to overlook an even more crucial point, Wynes says. “It’s missing this idea that individual actions aren’t taken in isolation and that you’re part of a culture. People look around at one another to understand how they ought to behave.”

There’s research to back up this notion. A 2016 experiment on the Stanford University campus found that people in a cafeteria were more likely to pick a vegan meal if they were told that 30 percent of Americans have started to make an effort to limit their meat consumption. A 2015 study from research at the University of Connecticut and Yale found that people are much more likely to install solar panels on their homes if their neighbour already has.

Though Russell rarely talks about his low-carbon life to his colleagues, he sometimes talks about climate with his students. But he’s not sure he inspires them to care more. “As an academic, I’m supposed to be a leader. I might not go on about it often, but I’m trying to show that in terms of my actions,” he says. “But no one notices.”

I can’t help but think that they do. He mentions that one student emailed him recently to thank him for inspiring them to go vegan. And I think of how this conversation with Russell has already made me consider booking a train ride home to Edmonton instead of a cheap flight. I think about a 2017 survey of over four hundred people at Cardiff University, where about half of respondents who knew someone who had given up flying because of climate change said they fly less because of this example. Only 7 percent of respondents said that knowing someone who doesn’t fly hadn’t changed their thoughts on flying at all.

Russell has always believed the most effective way to make change is quietly, by living his life according to his rules, answering questions when asked, and voting with his wallet. Right now, though, he worries increasingly that it’s not enough. “I don’t know if there’s enough time,” he says. There’s less than twelve years to radically change the carbon footprint of the entire human race.

So now is when he’s coming to terms with his, as he sees it, fundamental failure—a reluctance to make things really awkward, to confront people more. “If someone asks me, I’ll tell them,” he says, “but I’m not a strong enough personality.”

Psychologists have written about a host of cognitive biases that can contribute to mass inaction on climate change. Generally, humans are more likely to think that the present is more important than the future, for example. We care less about generations that come after our great-grandchildren. There’s the bystander effect, which makes us assume someone else will step up in a crisis. Or the sunk-cost fallacy: we stick with something—say, an environmentally detrimental, trillion-dollar industry—just because we’ve already sunk a ton of time and money into it.

At one point, Russell began seeing things slightly differently. The year he became vegan and committed to stop flying, he was working on his PhD. His academic work focuses on the role of bureaucracy and complicity in making the Holocaust possible. He also became fascinated by Stanley Milgram, the mid-century American social psychologist whose experiments questioned to what extent people are willing to obey instructions, even if it causes another person harm. Milgram was horrified by watching the Nuremburg trials, where Nazis often defended themselves by saying they were just following orders.

Milgram’s experiments are often touted in first-year psychology classes: an unassuming participant was told they were the “teacher” and that another participant behind a glass wall was the “learner.” The learner would answer questions, and the teacher was told to press a button and deliver an increasingly high-voltage shock each time the learner got an answer wrong. In reality, the person behind the glass was an actor. But more than 65 percent of participants would deliver a lethal electric charge if ordered to do so.

The Milgram experiments are well known, but Russell had never seen them applied to the idea of climate to explain our mass inaction. In 2007, however, immersed in studying the experiments, it was impossible to separate the two.

I balked when I first heard him compare torture experiments to societal inertia on climate change. It seems too easy to throw around the Holocaust when trying to make sense of anything that’s human and inexplicable. Russell says some of his students have a similar reaction.

But then he clarifies himself: “We can say that the government needs to be stronger, but they can turn around and say, ‘We’re not responsible, we’re just giving the people what they want. What they want are jobs,’” he says. It makes sense—the blame can be displaced.

He dedicated his first book, Understanding Willing Participants, Vol. 1, to Valerie Morse, a well-known Kiwi activist. In 2010, three years into his newly low-carbon life, Russell and a group of animal rights activists were standing with signs in front of the Austrian embassy in Wellington, NZ, protesting criminal charges against animal activists. Morse came across them on the street. “Good on you for protesting,” she said, before leaning in and whispering to Russell, “But you know, nobody’s noticing you. Follow me.”

She led them, placards in tow, and kicked open the glass-doored embassy. Holy shit, we’re going to get arrested, Russell panicked. Morse strode into a boardroom, first swiping the contents of a receptionist’s desk onto the floor with her arm, and started screaming at the people present, then turned and walked out.

“Now they know who you are,” she said to Russell. He got shivers.

Russell is rapt when he talks about Morse. “She spits on politicians,” he gushes. “This is what’s needed—strong people who aren’t afraid to say what they believe in and make people feel guilty for the dangerous course in which we’re headed.” He also speaks admiringly of Greta Thunberg, the sixteen-year-old Swedish environmentalist who delivers measured, scathing speeches to European governments.

But Thunberg also frequently acknowledges the key difference between herself and most people, the thing that makes her approach possible. “You only speak of green eternal economic growth because you are too afraid of being unpopular,” she said in one such speech, in December. “But I don’t care about being popular. I care about climate justice and the living planet.” Thunberg has Asperger’s, a form of autism. When an interviewer asked how the neurological difference has influenced her activism, she answered bluntly. “If I didn’t have Asperger’s and if I wasn’t so strange,” she said, “I would have been stuck in this social game that everyone else seems to be so infatuated with.”

Russell is not disconnected from the social game. Nor is he unaware that being that way—seemingly average—can be a strength. He knows that the same radical people he admires probably turn others off. He says his wife, for example, has converted many more vegans than he has because she can speak so gently and eloquently about the benefits.

In the final chapter of Russell’s recently published book, Understanding Willing Participants, Vol. 2, he explicitly parallels global inaction on climate change to the Milgram experiments. Any reasonable person would say it’s morally wrong to continue doing things that are undoubtedly going to cause worldwide environmental catastrophe. So why do we keep doing them?

What the Milgram experiments and climate change have in common, Russell says, is not just that it’s possible to displace blame, but that there is no clear party to blame. Milgram’s participants were ordered by a shady authority figure to deliver the electric shocks. Consumers in the developed world can blame governments, the government can blame voters for not making environmental concerns a priority, corporations can blame insufficient consumer demand, and citizens of the developed world can blame greedy corporations.

This circling of blame also suggests something dark: that each party acknowledges the problem, but without really caring enough to take ownership. “Collectively, we refuse to sincerely confront an issue likely to bring about ‘civilization collapse’ because of what are perceived to be far more pressing, immediate, interests—the promise of a higher standard of living, greater economic growth, more jobs, and the prioritization of convenience over sustainability,” Russell writes in Understanding Willing Participants, Vol. 2. “Privately we all know that by the time life on earth starts getting really nasty...we’ll all be dead.”

In his closing paragraphs, Russell notes that Milgram wasn’t quite sure what to make of the results of his experiments. It didn’t show people’s innate obedience to authority—that wasn’t quite accurate or malevolent enough. Russell thinks Milgram’s experiments show that powerful people can rearrange society in a way that forces less powerful people to pick between personal interests and the wider societal good. It reminds me of a Tom Moro cartoon of a man sitting around a cave fire with three kids. “Yes, the planet got destroyed,” the text reads. “But for a beautiful moment in time, we created a lot of value for the shareholders.”

But Russell tells me one of his newer thoughts about the experiments: that the experimenter can convince normal people to do horrible things simply because they don’t want to cause a scene. “People who are concerned about getting along or make a scene are easiest to manipulate,” he says. Milgram noted that quite a few participants tried to get away with pretending to press the shock-inflicting button, so they didn’t offend the experimenter, while not harming the person who was supposed to get shocked. “When I look at those experiments, I know I’m just the kind of person that can be bullied, railroaded, into doing something bad,” he says.

It’s a conclusion that I first find depressing at best, but Russell takes another spin on it. “The little people have to take responsibility. Little people from the bottom up can make a difference,” he tells me. It does make me more hopeful. Powerful, shadowy figures, oil executives and politicians, aren’t the only people ruining the planet. Absolutely. It’s also us. And yet maybe we can be powerfully contagious, just by being little, by being normal, by being copyable.

Writing this story has made it harder to fall asleep at night. The night I finished the final draft, I turned to my partner in bed and asked him if he was scared about the world burning, too.

“Aren’t people doing things about it, though?” he said.

“Who are the people?” I asked my ceiling.

Being on Twitter, where I can read hundreds of panicked, unfiltered musings about the impending climate crisis in a single sitting, surely doesn’t help. I shared a Vice article I saw with Russell: “The Climate Change Paper So Depressing It’s Sending People to Therapy.” The paper being referred to was written in 2018 by Jem Bendell, a professor at the University of Cumbria in the UK. He speaks about similar conditions outlined in the UN report, but in prophetic literary terms. “When I say starvation, destruction, migration, disease and war, I mean in your own life,” he writes. “With the power down, soon you won’t have water coming out of your tap. You will depend on your neighbours for food and some warmth. You will become malnourished. You won’t know whether to stay or go. You will fear being violently killed before starving to death.”

I wondered what Russell would think of it. Was this his inner narrative, too?

It actually brought out a quietly hopeful side to Russell I wasn’t expecting. First, he wondered whether this doom narrative could dissuade people from trying to reduce their emissions, or to think, as he put it, “Well, I guess it doesn’t matter how I live—stuff it, we’re all doomed…” I wondered the same: whether articles like this just keep people’s heads in the sand, while making the Russells of the world feel even worse because despite their best efforts, the world is still ending.

But Russell also wondered what if—just if—the devastating conditions Bendell prophesized don’t come true. “It could be incorrect,” he wrote. “I feel I have a moral obligation to continue trying to reduce my greenhouse gas footprint (even if it turns out to be a complete waste of time).”

The idea of trying my best, even though it might be a waste of time, resonated with me. There’s the small, shiny kind of hope: it might not be a waste of time. It’s well understood among psychologists, after all, that having a greater sense of control dissuades feelings of anxiety. If I’m dreading sending an email, for example, the only thing that calms my panic is actually pushing through my anxiety wall and sending the email. Taking my own little climate actions is kind of like that, except the horror is bigger. There’s something about knowing I’m doing something that keeps the existential dread out of my immediate eyesight. As I’m riding the bus or buying unpackaged tofu at the waste-free grocery store, the doom is still there, rattling, but it’s quieter. I look up recipes for tofu scramble, book my VIA Rail trip to Alberta and try to keep the dread at bay.

I don’t know what’s worse: living with your head in the sand like most of my friends and family, or being like the Russells or Bendells of the word, so acutely aware of the planet’s destruction. It would be so nice to just not care, or to know that I was old and not have much time left on the dying planet. But it’s pointless to think that way. I’m twenty-five years old and I’ve seen it and I can’t unsee it now. Neither can Russell. We’ve both noticed there are people in our lives who talk about how scared they are but don’t seem to do anything about it. Is the difference that they haven’t truly felt the doom yet?

There’s one thing weighing particularly heavily on Russell’s mind right now: his wife just had their baby, a daughter. Their compromise was to have just one child, a low-carbon one. She arrived the day after a snowstorm in January and his voice glows, briefly, when I ask about her: “She’s so delightful.” I asked him if there are moments alone with his daughter when he’s able to quiet the doom rattling, when he’s able to enjoy life. He says he can, sometimes. It makes me glad.

Russell oscillates all the more between anger and a dark kind of optimism, necessitated maybe only by the fact that he has a daughter now to harbour optimism for. He thinks about the impact on her of being all doom and gloom. “What kind of parents would we be then?” he asks. “But also, being ignorant, carrying on as if nothing’s a problem, what would my daughter think if we went down that course?”

He wishes it were easier to maintain normal human relationships with people without flying to see them. I do, too—I can only imagine the expressions Russell is making as he talks about his trek across the Pacific. I can imagine his brown—or were they blue?—eyes light up the same way his voice does when he talks about butchering karaoke.

Still, talking helps, he says—maybe he could encourage more people to try harder. This is why he agreed to talk to me, he says. “Maybe this is a way for me to express myself.” And even though I can only hear his voice, I do feel like I know Russell. Maybe because of how much he’s told me, maybe because I see part of my own existential anxieties in his own.

These questions of distance are especially difficult for Russell now, especially since his parents in New Zealand and sisters in Australia want to visit his four-month-old. “I don’t want to be like ‘Look: I have an ethical problem with you coming on a plane to see my daughter,’” he says. “I’d just feel like an asshole.” He says he’d fly home if his parents or sisters were dying, without question. But in this case, he tried convincing them to hang out with the baby over Skype instead, to no avail; they’re coming anyway.

He repeats something he’s said at least five times over the course of an hour-long conversation. “I feel,” he says, “like a difficult person.”