Illustrations by Nicole Xu

Illustrations by Nicole Xu

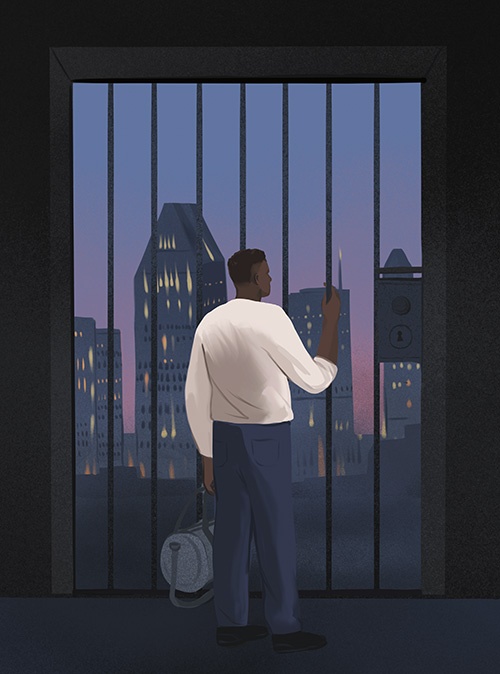

A Life in Limbo

Applying for permanent residency on humanitarian and compassionate grounds is a last resort for migrants in Canada. Christopher Chanco explores a convoluted system.

Mamadou Batchily first laid eyes on his partner Diallo in Diéma, a small town in southwest Mali. For months, Batchily would travel from the village where he was raised, about an hour’s walk away, to go see her at the restaurant where she worked. Their meetings always happened in secret. Diallo was one of few Christians in a predominantly Islamic country. While Diallo’s parents welcomed Batchily warmly, his own family didn’t approve of the growing romance between them.

Batchily belongs to the Soninke tribe, one of over a dozen ethnolinguistic groups scattered across Mali, Mauritania, Senegal, and other West African states. The Soninke gradually abandoned Indigenous practices in the eleventh century, converting by and large to Islam. In Batchily’s community, one must remain both Soninke and Muslim from cradle to grave.

Defying cultural and familial expectations, Batchily married Diallo about a decade ago. “Not only did I marry someone who wasn’t from my own community, I married a non-Muslim,” he says. His father wanted nothing of it. “But I told him that I loved my partner, and that I was going to marry her, and that was that.”

Batchily received death threats from his family and had weapons aimed at his chest. His father tracked him down and beat him, repeating a pattern of abuse he had endured since childhood. “My parents wanted to kill me to preserve their image in the eyes of the community,” he says. He could hardly turn to the police for protection, as this kind of conflict tends to be deemed an internal family affair.

For some time, the couple lived in hiding with Diallo’s family. But the threats from Batchily’s father, uncles and other members of his community only grew. Diallo’s family’s protection was no longer enough. The couple was constantly on the move for more than five years. The births of their two sons only complicated things further, limiting their ability to move around and adding to their safety concerns.

Knowing he was a danger to his own family, Batchily made the painful decision to leave Mali six years ago. A childhood friend reached out to a passeur, essentially a human smuggler, who convinced Batchily that he could apply for refugee status in Canada. His friend paid thousands of dollars for the passeur’s services, which included supplying Batchily with a passport and a visa bearing a false name.

Legal pathways are often limited for migrants fleeing to Canada under duress. It’s never been easy to “get a visa from countries like mine,” says Batchily. Visa applicants from Africa have more trouble securing permission to visit Canada than people from any other continent; the approval rate for applicants from Mali is only 60 percent.

Batchily knew trying to organize a clean exit with his wife and young children would have multiplied the risks and costs. His plan was to immigrate first, with the hope of eventually sponsoring his loved ones, so they could finally live together in peace. His partner and children remained in Mali under the protection of his wife’s family, still receiving occasional threats from his relatives.

Crossing Mali’s southern frontier in 2015, Batchily boarded a plane in Côte d’Ivoire that took him to Turkey, then Canada. He applied for asylum at the Montreal airport, revealing the truth about his situation. Entering Canada through clandestine means, even with a false passport, is not necessarily a problem, says Richard Goldman, a refugee lawyer at Montreal City Mission, a nonprofit that advocates for vulnerable communities, including migrants. “It is widely accepted in international humanitarian and refugee law that people arrive somewhere with false papers before applying for asylum,” he says.

On the other hand, asylum seekers must eventually be able to prove their real identities for their applications to be considered, Goldman says. Since the passport and visa Batchily used bore the name of another person, and he had no real papers, he was unable to convince Canadian border officials at the airport of his real identity. It’s a problem that has haunted him ever since.

Batchily was handcuffed at the airport and forced into a small van. Despite being fluently francophone—French is Mali’s official language—he couldn’t, at first, make sense of the border officials’ Québécois accents. “They were talking too fast. I couldn’t understand a word they were saying,” he says. The process was humiliating.

He was brought to the Laval Immigration Holding Centre on the outskirts of Montreal, a former prison surrounded by high fences and barbed wire. It’s one of three immigrant detention centres in Canada—Ontario and British Columbia host two others—managed directly by the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA). In winter 2021, detainees at the Laval facility, some of whom had contracted Covid-19, went on at least three hunger strikes over poor living conditions and lack of access to health care throughout the pandemic.

Migrants, often detained without criminal charges nor a mandate of arrest, can also be jailed in provincial prisons alongside convicted criminals, and even placed in solitary confinement for extended periods of time. Since the start of the pandemic, a growing number of immigrant detainees—currently about half of all migrants arrested by the CBSA—are being held in provincial jails. Migrants who are not held on criminal charges “experience the country’s most restrictive confinement conditions … handcuffed, shackled, searched, and restricted to small spaces with rigid routines and under constant surveillance,” according to Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch.

The detention of undocumented people is normally justified on the grounds that someone is believed to be a flight risk, or that someone’s identity, like Batchily’s, is unknown. Migrants whose citizenship remains a mystery cannot be sent back to their country of origin, since a deportation can only take place with the home country’s consent. Until their identity is established, many people live in legal limbo as they await deportation or take steps to change their status through an asylum claim.

Between 2018 and 2019, Canada detained over nine thousand people, most of them for administrative reasons—that is, without criminal charges. Canada is one of the few western nations where a migrant can be locked up indefinitely. By contrast, most European countries have imposed temporal limits on detention, as has the United States, where migrants must be released after six months for their cases to be adjudicated, unless they’ve been convicted of a crime.

Batchily spent about one month at the Laval detention centre before finding a lawyer through Malian contacts. Having applied for asylum at the airport, he was deemed eligible to pursue his refugee claim. He was taken, handcuffed, to a couple of hearings before the Immigration and Refugee Board (IRB). The IRB is a sort of jury that decides whether an asylum seeker can go on to receive refugee status, after which, they can eventually apply for permanent residency. The IRB can also intervene to determine whether a detainee should be set free or stay imprisoned, and for how long.

As a quasi-judicial administrative tribunal, the Board oversees the detention review process every thirty days to decide whether someone should be liberated. Once an asylum seeker is approved for release, certain “alternatives to detention” exist: migrants can be released into the community (on the condition that they report to the CBSA on a regular basis), pay a bail, or have an organization like the Salvation Army take responsibility for them. Like a court, a member of the IRB adjudicates between a detained migrant and the CBSA, which might, for example, argue that someone is a security risk or won’t show up to their asylum hearings and must therefore remain in detention.

In Batchily’s case, the IRB decided in favour of him pursuing his asylum process in relative freedom, securing his conditional release from the detention centre in the summer of 2015. To be able to continue his asylum claim, Batchily’s wife mailed him his real passport, his Malian national identity card, their marriage certificate and the birth certificates of his children, documents that would later be used to assess his refugee claim.

As an asylum seeker, Batchily was offered a room at a YMCA in Montreal, where he lived for a few weeks before finding an apartment that he shared with a roommate. For a time, he received a small allowance from the provincial government as part of his refugee claim. He also received the right to a work permit, which he renews yearly.

Over the next couple of years, Batchily was subjected to additional hearings with IRB members who probed into every corner of his life. The classic definition of a refugee is a person with a “well-founded fear” of violence or persecution back home. But an asylum seeker must also prove that there are absolutely no alternatives to exile to guarantee their safety.

While Batchily’s story was compelling, he struggled to convince the IRB of the merits of his case. Time and again, he brushed up against the problem of proving he was who he said he was. The documents he provided, while enough to secure his release from detention, were repeatedly called into question.

The IRB rejected his asylum claim in the winter of 2018. Batchily and his lawyer appealed the decision with the hope that it might be reversed. But he quickly learned that seeking refuge in Canada, hailed internationally as a model of hospitality, is far from simple. Instead, he entered a Kafkaesque system, where a series of opaque decisions would determine his and his family’s fate. That system proved even less welcoming in the years to come, amid a pandemic and growing instability in his home country.

“I chose Canada because I was told that it was a country that protected the persecuted—the country that was the best placed to protect refugees,” he says. “But the image that Canada projects abroad doesn’t reflect reality.”

On a spring day in 2018, Batchily climbed into the bowels of a giant dough processor. He was working at a factory that makes bread for Première Moisson, a popular bakery chain in Quebec. His job included scraping down the machine that slices the dough into loaf-sized pieces. The machine swung open and closed like the wings of a butterfly. Crack. Crack. Crack.

There was more dried dough glued to the machine than usual. Batchily stopped the contraption and scraped, scraped, scraped. “Can you turn it back on?” he asked a co-worker, before stepping back out. She restarted the machine and the freshly scraped, floury dust and debris floated to the bottom. Batchily paused the mechanism again. Believing his colleague had already left, he re-entered the funnel and scraped, scraped, scraped. Just then, his colleague set it back in motion. Batchily let out a scream as his lower legs got trapped between the butterfly’s wings. Crack. Crack. Crack.

Over the next eight months, Batchily was in and out of three hospitals, undergoing several surgeries to repair his crushed tibias. His medical bills were paid for by the province. The accident happened just a few months after he started at the factory, the latest in a string of odd cleaning jobs. “I wasn’t looking for anything special when I arrived in Canada,” he says. “I just needed to work. I was thinking about my family.” But since the accident, Batchily suffers constant pain and hasn’t been able to return to work. He is still undergoing physical and psychological therapy.

Because of the trauma, he can’t imagine himself working with machines again. “I am no longer who I once was. I am constantly tired. Sometimes I sleep just to be able to find myself again,” he says. Today, he walks with a cane and metal plaques fill the gaps where his tibias were. His doctors say he has lost about 40 percent of his physical capacity. Since his release from detention in 2015, Batchily has been reporting to the CBSA every six months, promising not to resist arrest should he again be detained and subject to deportation. While he was still undergoing treatment for his legs, he once showed up before the Canadian border authorities on crutches to reassure them that he wouldn’t run away.

Still, when Batchily does return to work, his papers and work permit allow him to change employers. He also receives cheques twice per month as a result of his accident and can send money home to his family. That makes him, in some ways, better off than migrants who are completely undocumented. Migrant justice advocates have long pointed to the vulnerability and exploitation that results from living in protracted limbo. Without legal status, the undocumented are at the mercy of employers who can call the authorities on them at any moment.

“We’re like hamsters in a lab. We keep running—the wheel turns and turns—but we’re stuck in the same spot,” says Farid Talbi, a former asylum seeker from Algeria, who is a member of the Montreal chapter of Solidarity Across Borders. Having lost his status, he has worked under the table at a factory for years. He receives lower pay without benefits for working the same number of hours, and for completing equivalent tasks, as his co-workers who are citizens.

But even for those here legally, labour abuses are frequent across the board, affecting everyone from farmhands and factory workers to migrant nurses and caregivers. In Quebec, the number of serious work accidents among temporary foreign workers has tripled since 2015. A recent deal struck with the federal government allows Quebec companies to grow the share of foreign workers they recruit each year—even as the province is increasingly restricting access to permanent status for those occupying posts in low-wage, “low-skill” sectors. Accessing public health care and basic services is also a challenge for those without permanent status.

The day after his own accident, Batchily received a call from his lawyer informing him that the appeal to his asylum claim had been refused. He was devastated, but he tried to reassure his wife and children that everything was going to be alright. He longed to be able to tell them in person, but he was starting to lose hope. “I asked myself whether, if the immigration agents were in my situation, they could have endured what I went through,” he says. The letters of refusal are like a death sentence. “When I read and reread the words, the stress sickens me. It would have been better had they killed me.”

Canada processed more than two hundred thousand asylum claims between 2014 and 2019. Prior to the pandemic, about 60 percent of asylum seekers managed to secure permanent status per year. Many of them waited years before a decision was made on their case. In 2019, thousands of applications that had been filed nearly a decade earlier were still sitting in limbo.

When an asylum claim is denied and all subsequent appeals have been exhausted, people like Batchily are left with one option to avoid risking deportation: an application for permanent residency on humanitarian or compassionate grounds. “All asylum seekers know, at the back of their minds, that it’s their last resort,” he says. It’s the only possible legal pathway for rejected asylum claimants and temporary residents, such as migrant workers and international students who, for one reason or another, have lost their status and become undocumented.

When seeking permanent status through the humanitarian route, “one is essentially asking for an exception to the application of the law,” says Pierre-Luc Bouchard, an immigration lawyer at the Refugee Centre in Montreal. The process is highly subjective. Canada’s Immigration and Refugee Protection Act stipulates that permanent residency can be granted if whoever is deciding on the case “is of the opinion that it is justified by humanitarian and compassionate considerations.” Nowhere, however, is the word “compassion” explicitly defined.

As such, the limits of sympathy are fixed by federal immigration agents, and then reinterpreted in the courts whenever migrants contest their decisions. The words of the first chair of the Immigration Appeal Board, in a case brought before the Supreme Court in 1970, are telling: whatever might incite in a reasonable person “in a civilized community, a desire to relieve the misfortunes of another” could justify an exception to the law on humanitarian and compassionate grounds.

Policies that determine immigration status belong to the realm of administrative law, which is why one federal agency, Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC), determines the fate of migrants. Applying for a visa or any sort of legal status—apart from asylum claims—in Canada “is similar to applying for a driver’s license,” says Bouchard. The process involves neither judge nor jury and migrants have limited recourse to contest the decisions of the immigration ministry.

Except that in the case of a would-be immigrant, the decision encompasses more than the right to drive. It’s about the right to a job with wages and working conditions equivalent to that of citizens, the right to send your children to school, the right to public health care, the right to sponsor and live with your loved ones. In other words, the right to plan your life somewhere without fear of having to leave tomorrow.

Released from hospital after months of therapy, Batchily decided to apply for permanent residency on humanitarian and compassionate grounds in the spring of 2019, a year after his asylum appeal was refused. He was entering uncertain territory. Of more than ten thousand asylum seekers who went on to become permanent residents in 2016–2017, just seventy-four people managed to do so through the humanitarian route. In 2018, the acceptance rate for humanitarian claims was around 64 percent.

That number dropped significantly after the Covid-19 pandemic began. The Migrant Rights Network has reported an unprecedented number of rejections since 2019. Data secured through an access to information request shows that the IRCC’s refusal rate for humanitarian claims rose to 70 percent by 2021. Syed Hussan, a member of the network, believes there’s been an unannounced policy shift on the part of the IRCC.

In a written statement to Maisonneuve, the IRCC said that “while statistics on refusals for H&C applications appear to be higher than previous years, in 2020 and 2021 the approval/refusal ratio is consistent with 2019.” A spokesperson says the numbers may appear skewed as a result of administrative delays resulting from the pandemic.

But Hussan and other migrant advocates insist that the rejections cannot be explained by that reasoning. The data suggests that immigration officers are rejecting a much higher proportion of fully processed applications since 2019 and 2020, especially when compared to the past five years when rejection rates varied between 35 to 40 percent.

Whether this is due to staffing changes or an internal policy shift affecting how decisions are made, it’s impossible to tell, says Goldman, the lawyer from Montreal City Mission. The answer may lie in how immigration agents are chosen, or trained to assess humanitarian applications.

The selection of immigration agents is an internal staffing decision on the part of the IRCC. Members of the IRB, by contrast, are independent of the immigration ministry and undergo extensive training in asylum law, and their conduct is open to public scrutiny through a formal complaints process. According to the IRCC, all immigration officers “receive the same rigorous training allowing them to assess and make decisions on complex applications.” This includes individualized coaching and special legal training to help them evaluate humanitarian claims.

Unlike asylum claims, which are judged by the IRB according to strictly defined criteria following international legal norms, those claiming status for humanitarian reasons are required to demonstrate the “hardship” they would face should they be sent back to their countries of origin. Here, again, much is open to interpretation. Humanitarian considerations cover a potentially vast spectrum of human suffering. In practice, hardship is assessed according to concrete facts to do with a would-be immigrant’s home country.

“Normally, one would look at the political and socioeconomic conditions of someone’s country of origin, and the difficulties that he might face should he be forced to return,” says Geneviève Binette, who for years handled numerous cases, pro bono, for unsuccessful asylum seekers at the Committee to Aid Refugees in Montreal. Would Batchily, for instance, be subject to discrimination or violence as a result of his gender, ethnicity or religious beliefs? Would he be able to find a job or access health care for an illness or injury?

The officer would then assess his ties to Canada: his ability to speak English or French, his work experience in Canada, any volunteer experience or other social engagements in Canada, family and friends in Canada. Anything, in other words, to prove his integration into Canadian society, as opposed to the links he might still have in his country of origin.

An agent deciding on a humanitarian case must also consider “the best interests of a child directly affected” by the application. Binette offers the example of children born and raised in Canada with virtually “no ties elsewhere and who might not even speak their parents’ native language.” But the well-being of those still living in their parents’ home country is—theoretically, at least—of equal importance.

Humanitarian applications allow for a broader range of potenital evidence to support asylum claims. Binette’s typical dossiers include boxes of affidavits, medical records, university transcripts, job contracts, tax forms, news articles and reports from human rights organizations and government sources. A humanitarian application must prove that life in someone’s country of origin is miserable enough to incite compassion. In other words, is life back home sufficiently insufferable?

Batchily is a news junkie. Tuning into Radio-Canada, TVA Nouvelles, TV5Monde and Radio France Internationale on a regular basis, he follows political developments around the world. He recounts events in Mali over the past few years with the confidence of a man who has documented, repeatedly and in precise detail, the situation in his home country for the immigration authorities.

He grew up in the south, not far from the capital Bamako, the poorest and most densely populated part of the country. Nearly half of Mali’s population, women and children especially, live in extreme poverty, a reality aggravated by the pandemic and persistent political instability.

But the real chaos began in the wake of the Arab Spring, says Batchily. The revolutions that swept across much of the Islamic world reverberated throughout West Africa and the Maghreb. The popular uprisings may have led to democratic reform in certain countries, but it also unleashed long-festering tensions elsewhere. For Mali, the Libyan civil war had devastating repercussions, inspiring a separatist movement in the north.

Then came the Islamists. Since 2012, armed groups like Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, and other armed factions that have proclaimed allegiance to the Islamic State, have waged a campaign of terror against the local population, including cutting off limbs, recruiting child soldiers, and enacting mass rapes and forced marriages. Mali’s ungoverned north is also a pit stop for sub-Saharan African migrants hoping to seek refuge in Europe across the Mediterranean, only to be pushed into slavery in Libyan camps.

The situation has gone from bad to worse in the years since Batchily has lived in Canada. The chaos from the north soon reached the country’s south. The inability to control the conflict triggered latent discontent in the army. Malians have witnessed three coups d’états since 2012.

The international community, with Canada and France at the helm, has supported several peace-keeping missions in Mali with modest success. But attempts at a democratic transition have failed repeatedly. Meanwhile, civilians continue to be caught between the abuses of the Malian army and the atrocities of the jihadists. The conflict has metastasized to neighbouring countries. Over two million people have been displaced in the Sahel since 2012, a humanitarian crisis compounded by the pandemic and climate change.

In August 2021, one UN independent human rights expert warned of the “grave deterioration” of the security situation in Mali. The nation is on the brink of becoming a failed state. These are facts recognized by the Canadian government, which has invested significant amounts of foreign aid into Mali.

Yet Canada risks sending Batchily back to a country with a government largely incapable of protecting its own population and which might even cease to exist in a few years. “Economically, things are bad in Mali. Socially, things are bad in Mali. Politically, things are bad in Mali. Nothing is going well anywhere in the country,” says Batchily, who can do nothing but watch from a distance and worry about his loved ones.

“I believe that [immigration officers] understand perfectly well what the situation is like in our countries of origin,” he says. He rejects the idea that most Canadians simply don’t understand what life is like elsewhere. “That they refuse to see it is intentional … it’s the West.” For Batchily, the grievances run deep. Mali was a French colony for nearly a century. “Westerners came to colonize us, to enslave us, and now they reject us when we want to come to their countries.”

Over five years, Batchily had gathered work experience, made friends and completed professional and second language courses. He thought all of this would work in favour of his application on humanitarian grounds. He also knew he wouldn’t receive the same quality of care in Mali as in Canada, which he believed might help his case.

Batchily has lost count of the number of documents he has sent the IRCC. Everything about him is in an online portal: his passport, his national identity card and his birth certificate. Certificates from the professional development programs and English language courses he has completed in Canada. Receipts of money transfers back home.

Then there are all the letters. To demonstrate his ties to Canada, Batchily has solicited notes from his entire social network, including friends in the Malian diaspora and at his local mosque. After his accident, his physiotherapist and psychologist wrote in support of his application. Batchily has laid bare his life history. He’s shared intimate details about his family with immigration officers he has never seen in person. He’s sent them photos of, and letters from, his children.

Despite all of this, Batchily’s humanitarian claim was refused and his file closed in January 2021. “They gave me many reasons for the refusal: mainly that they couldn’t establish my real identity, but also that I wasn’t well-integrated into Canadian society. Even that I wasn’t close enough to my own children. It’s shocking to see how much of that simply isn’t true,” he says.

Even his lawyer agrees that Batchily has done far more work on his case than others have. They both wonder why his case keeps getting refused. “I’m tired,” Batchily says. His interactions with the Canadian state have been with a faceless bureaucracy. “Those who are studying our files should try to see the human side of things.”

Batchily has turned to the streets for justice. He has participated in protests for the rights of the undocumented and religiously attends meetings organized by Solidarity Across Borders, which also provides financial support to migrants in need. He relies on the kindness of friends who come visit him from time to time. An elderly Quebecer he met at the hospital phones him on a regular basis to check up on him. A practicing Muslim, his brothers at the mosque also provide him with spiritual support.

Batchily and his lawyer have submitted a request for the IRCC to reopen his case and perhaps reverse the decision. It has been almost a year and he is still waiting for a response. If that fails, he might submit a new application, with new evidence in support of his claim, or bring his grievances to court.

Contesting a decision at a federal court can be a prohibitively expensive process, costing thousands of dollars in legal fees and a lot of courage. “There is a certain degree of distrust in the legal process,” says Bouchard, from the Refugee Centre in Montreal. Many migrants, coming from societies where the rule of law is at best an aspiration, hesitate to continue the fight in Canadian courts. They are afraid of the repercussions from state authorities from which they have only known violence and corruption.

For humanitarian and compassionate applications, adds Goldman, the decision made by an immigration officer is harder to overturn than in the case of an asylum seeker. It must be contested on the grounds that the officer’s decision was “unreasonable” rather than simply wrong or unethical based on the evidence presented in the case. In other words, the rationality of the judgement supersedes compassion—the very principle on which humanitarian applications are otherwise based.

Barring fundamental changes to the law itself, the IRCC could adapt its policies to allow for clearer, more transparent, and predictable decision-making on humanitarian cases. It could also invest in retraining its staff to emphasize the human aspect of the program. Binette points again to its “inherently discretionary” nature which lacks the robust mechanisms of the asylum process and depends largely on the judgement of individual officers.

For migrant justice advocates, the problem is systemic. While Canada prides itself on the diversity and inclusion of its immigration system, it is in fact a highly selective one, oriented toward vacuuming up middle- and upper-class people from overseas, while penalizing those from working class backgrounds and low-income countries, for whom most other avenues toward permanent status are, at best, a walk in the desert with no clear destination. The impacts on mental health and on basic human rights, including labour protections, are clear for thousands of migrants who are already living and working in Canada.

In the context of the pandemic, the Canadian government has launched new pathways facilitating access to permanent residence for those on temporary status, including the “guardian angels”—asylum seekers who worked in essential sectors throughout the pandemic. The IRCC says the program is open to “failed claimants and those with pending claims who provided direct care to patients in health-care institutions across the country.”

But many angels are in limbo, caught in a tug-of-war between federal and provincial governments. The Quebec government has sought to restrict access to the program as much as possible. Most asylum seekers who have become permanent residents through this pathway live in other provinces.

For the Migrant Justice Network, these efforts aren’t enough, especially in light of the recent rejections of humanitarian applications. Even as Canada keeps promising to increase the numbers of migrants and refugees it welcomes—and has fallen short of its immigration targets as a result of the pandemic—it has not matched branding with policy. “Right now, Canada needs immigrants and with Covid-19, the simplest thing to do is regularize and give permanent residency to all migrants already in the country, including undocumented people. Instead, we see immigration officials arbitrarily doing the opposite,” says Hussan.

In the meantime, the moral dissonance between Canada’s treatment of asylum seekers and the image it projects overseas remains stark. “What I have lived through, frankly, it’s deplorable. I never thought that Canada would treat people in such a way,” says Batchily. His loved ones are still in Mali. Without permanent residency, sponsoring his family is impossible. “My children call me all the time. I try to comfort them, saying that everything is going to be alright,” he says. “But my children have grown up without a father.”

One late summer afternoon in 2021, Batchily and I are walking to the metro station on Mount Royal Avenue. It’s his first time here. Prosperity surrounds us. Rows of organic grocery stores. Free books and furniture on the sidewalks. Beautiful, sharply dressed professionals sipping beer on patios. And everywhere, stickers of solidarity promising ça va bien aller. A Première Moisson looms up ahead. Young families line up to buy the pastries that Batchily once helped make. We don’t see, he says, le côté obscur des choses. The dark side of things.

“When you look towards the future, but it’s sealed shut … it’s not easy,” he tells me. “The only thing that can give me hope, the hope to move forward, is permanent status. In the meantime, the door is shut.”

Christopher Chanco is a freelance journalist based in Montreal. He covers human rights, international development, conflict and migration, and has written for Haaretz, Dissent, Jacobin and New Canadian Media.