Poetry is More Akin to Song Than Conversation: An Interview With Jim Johnstone

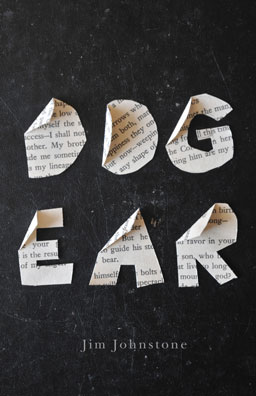

Jim Johnstone is the author of The Velocity of Escape (2008), Patternicity (2010) and Sunday, the locusts (2011). He is the recipient of a CBC Literary Award, the Fiddlehead’s Ralph Gustafson Poetry Prize and Matrix magazine’s LitPop Award. He is the poetry editor at Palimpsest Press and an associate editor at Representative Poetry Online. His most recent collection of poetry, Dog Ear, was published in 2014. He lives in Toronto.

Chad Campbell: Let’s start with my favourite sequence in Dog Ear, “Inland,” which opens “Left unaided to temper the seam of/a mechanical wing, we release our/cloak-pins, set to kindling flares.” Were you in a plane crash?

Jim Johnstone: Not unless turbulence counts. I’ve spent a lot of time contemplating plane crashes though, particularly while flying. I’m still not comfortable with the notion of bolting through the air at eight-hundred kilometres per hour in what amounts to a metal tube.

CC: In “Inland,” the injury and disorientation of the speaker (“I gasp, newly pneumonic, a storm”) and, geographically, being lost (“Newly transient, old growth/afire, we cling to suitcases like/folding armor”) seem perfectly matched with the one-step-forward, one-step-back of the poem’s linked ends and beginnings. How far into the writing did you know that “Inland” would be a crown of sonnets?

JJ: I planned the sequence fairly meticulously before writing it. A corona seemed the perfect form to tell the story, which is a fictional retelling of Frederick Banting’s 1941 plane crash in Newfoundland. There are some key differences between the true story and my account, where I take the liberty of having the protagonist live, as opposed to Banting, who died of exposure after the accident.

CC: Fiction writers often talk about holding conversations with their characters. Is there a poet’s counterpart to this? Did you feel as though you had any companions writing Dog Ear?

JJ: In my experience, poetry is more akin to song than conversation. So I sing. When Dog Ear was released, Sharon Suzuki-Martinez asked me to put together a list of songs that influenced the book, which was published on her website The Poet’s Playlist. The concept made sense to me: so many of the emotional textures in the book are taken from particular musicians or songs.

CC: How long after Patternicity, which appeared in 2010, did you start writing the poems that would become Dog Ear?

JJ: I’m always writing, but I don’t publish everything I write. While I tend to favour collections of poetry that are loosely themed, I think it’s crucial to find a new voice for each project. That sounds obvious, but writing against voice is very difficult and something I continually struggle to do. I threw out about a year’s worth of material between Patternicity and Dog Ear. This seems to happen with every book. I need at least that much time to write my way into something new, something that doesn’t sound like a hybrid on the road between manuscripts.

CC: Were there any changes in your writing practice as you wrote Dog Ear? The where or how? Inventive procrastinations?

JJ: I’ve enjoyed a kind of transience in my adulthood, and as a result, my writing process is often defined by where I write. Dog Ear was the product of settling into a new neighbourhood. In some ways it was a product of comfort, of having enough space to procrastinate. For me, walking, thinking and reading are essential to composition, since poetry requires an indefinite mindset. The majority of the poems in Dog Ear were conceived in Parkdale [in Toronto’s west end], which has served as my touchstone for several years now.

CC: How did the book’s title come about?

JJ: As a title, Dog Ear came fairly early in my writing process. Initially, I used it as an impetus to write poems that deserve a second look—the kind of work that might be dog-eared. But the title also charges the reader to think about the way a book of poetry is curated. Why did the author choose these characters? These moments? When I write, I’m conscious of plotting a narrative that’s filtered and compressed into a series of digestible morsels, dog-eared from my experiences.

CC: “…while I swore the world/I’d created would double like a hand/beneath my own, it merely stretches/before me in consolation. There, there.” There is a bittersweetness that seems to run under those moments in your poems that speak to the act of writing. After four books, would it be right to call, at least in part, your relationship with language a bittersweet one?

JJ: Yes. My poems never turn out quite the way I initially envision them. I’d chalk this up to potential—when I write, there’s palpable excitement, the feeling that I could finally be getting things right. In that moment, a world of possibility branches out on the computer screen and the poem contains a sort of latent magic. Of course, this shifts when the final word finds its place. There’s a sudden coagulation, a finite limit that’s reached like a hand that “stretches before me in consolation.” Strangely, the poem you quote, which is the title poem of the book, is one of the few instances where I feel like I was able to produce the poem I had initially envisioned.

CC: In an interview with the Paris Review, A.R. Ammons discussed John Ashbery’s tendency to “have the poem occur on the occasion of its occurrence” (and not under “the force of inspiration”). Ammons called it a brilliant point of view, but said: “That’s not how I work.” Do your poems tend to find themselves on the page, or do you wait for inspiration?

JJ: I love that Ashbery quote. I’d say that embracing occurrence is the primary way my writing process has changed over the years. I compose in my head now, taking what I remember to the page when I have time in front of a computer. Sometimes this doesn’t happen for months, since editorial and critical projects are always building up. So, what occurs, stays.

CC: Do you spend a long time revising?

JJ: Sometimes it feels like I spend all my time revising. That time feels like work. There’s a stark contrast between writing and revising as far as I’m concerned—writing is creative, joyous, almost ecstatic, whereas revising is necessary if you want to publish your work. There are times when I leave my initial draft in a journal and keep it for myself.

CC: What would you say is being preserved, so to speak, in the act of keeping an initial draft for yourself?

JJ: Writing is very intimate—that’s obvious. But when you’re used to publishing, privacy becomes a luxury. I find holding back work refreshing; as long as they remain unseen, my poems belong to me completely. The same principle is necessary in a healthy relationship or friendship. Without mystery, the self can suffer.

CC: There seems to be a tension between your need for comfort to produce new material and those things that push you out of your comfort zone, a sort of process of dislocation and assimilation. Not unlike the movement of empathy, in that there is a stepping outside of and return to oneself involved.

JJ: I’d go further and argue that poetry is an empathetic art form. Poets do so much with so little—every nuance is considered and reconsidered—that the very nature of poetic composition is an empathetic experience. Of course, understanding and feeling aren’t mutually exclusive, but poetry certainly functions on both levels for me, providing insight that I rarely get from other activities.

CC: I searched the formula/epigraph from your poem “Love in a Closed System”—M1 V1 + M2 V2 = (m1 + m2) v—and an article on “Elastic Collisions” was the first result. Can you speak a little to your incorporation of these formulas in your work? Do they tend to come before you write a poem or after?

JJ: Jason Guriel once compared my equational epigraphs to graffiti. I’ve always liked his interpretation, because the average reader won’t take much more from them than that. To me though, formulas are a form of attribution, acknowledging the kernel of thought that led to a poem. I consider the poems I’ve written this way to be parables that physically illustrate scientific principles.

“Love in a Closed System” is a textbook example of an elastic collision, which is taught in classrooms by describing a car accident. Such collisions are also taught using a closed system to minimize the factors that could influence energy transfer, in essence to simplify the scenario. My own take on this concept is more human, but I hope it retains the spirit of inquiry that distinguishes scientific thought.

CC: Reading other writers is often talked about as a way poets prime themselves to write. I was at a talk given by poet Robert Hass not too long ago, and he talked about the opposite effect: that there are some poets he admires, but who sort of stun his own writing. Do you have any writers you admire, but whom you steer away from before you write?

JJ: Absolutely. I actually stay away from my favourite poets: Frederick Seidel, Earle Birney, Larry Levis. They all have such distinct voices, which is why I love them. It’s also why poets who imitate them sound derivative.

When I’m writing I also try to stay away from poetry—or as much as I can. I find that reading material out of my comfort zone helps me when I’m trying to create. Let’s say Scientific American. Or Maisonneuve.

CC: If you think back over your four books, what is the most important shift you see in Dog Ear? You spoke once in an interview about Larry Levis’ migration towards the longer line. Can you forecast any changes in your work?

JJ: As opposed to Levis, my poems have actually migrated towards a shorter line. I enjoy the control short lines provide; the way caesura slows a poem down. In that way, Dog Ear is more considered than anything I’ve written in the past. Still, your question is difficult to answer, since I tend to approach each poem as a self-contained entity. There’s fight in my process—against voice, rhetoric, sense. So that makes the future hard to predict. If pressed, I’d say that the forecast calls for continued combat.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Chad Campbell’s first collection, Laws & Locks, is forthcoming with Signal Editions in fall 2015. Originally from Toronto, Campbell is a graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. He lives and teaches in Iowa.