Be Less Boring: Drew Nelles on Rethinking the Traditional Magazine Structure

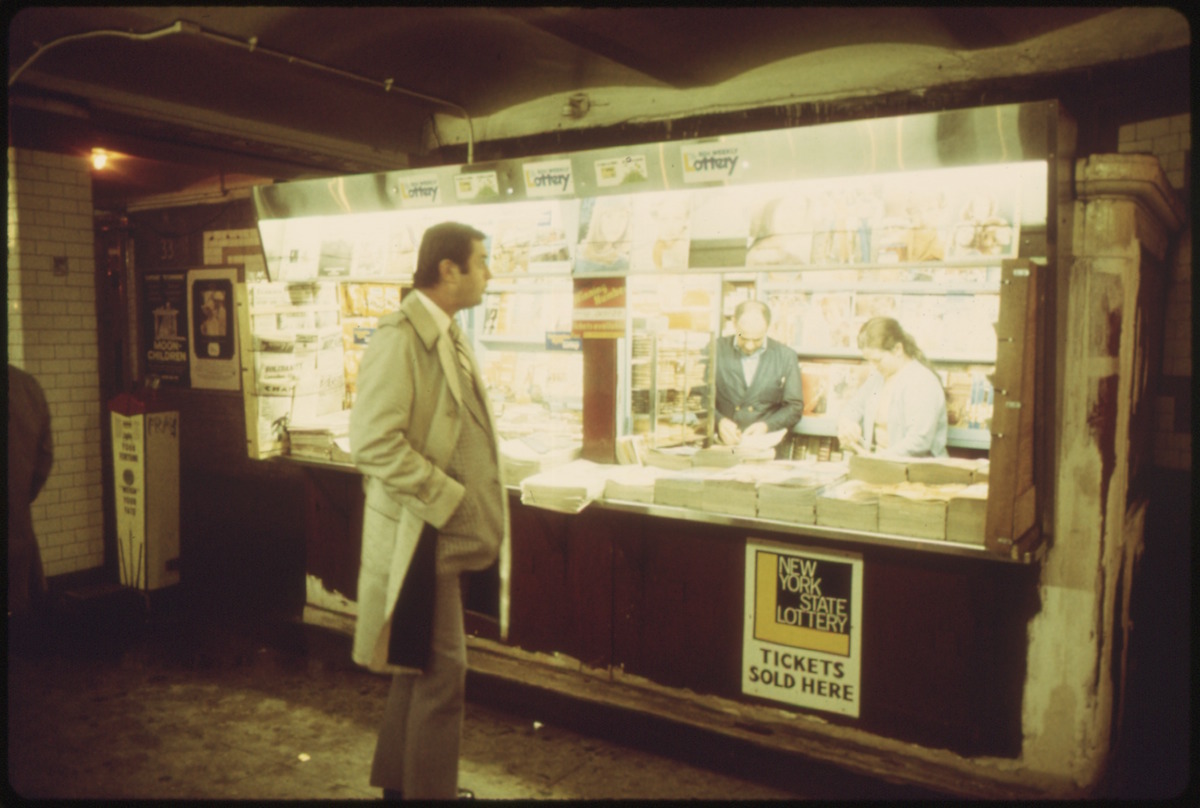

Photograph by Jim Pickerell.

In early December, Drew Nelles—formerly the Editor-in-Chief of Maisonneuve and most recently a Senior Editor at the Walrus—tweeted that there was a crisis in the way that print magazines continue to conceptualize their front-of-book (FOB) content (referring to the first third of a magazine that is usually comprised of the shorter features and columns before reaching what is called “the feature well”). He tweeted that it was “[hard] to defend clumping a bunch of short pieces together in the FOB, since short, unconnected pieces is 99% of the internet.” I caught up with Drew to ask him to expand on his front-of-book tweet string, and to better understand his love of the New Yorker’s front-of-book Talk of the Town section.

Andrea Bennett: The ongoing conversation about the impacts of web publishing on print magazines often centres around monetization of content, determining whether or not to limit access, or how to work subscriptions, that kind of stuff. But when you were tweeting about the crisis in front-of-book, you were alluding to a different type of impact that web publishing has had on print magazines, and I’m wondering if you can elaborate a little bit on that. What is it about the front-of-book that’s made it particularly vulnerable to the incursions of web publishing, and conversely, what is print still doing well for long features and cultural criticism?

Drew Nelles: I guess the point I was trying to make was just expanding on something I’d thought about a lot at both the Walrus and Maisonneuve, which is that there’s still a compelling case to be made for feature-length stuff in print. I think a lot of people would say that it’s still the best way to read something of that length—it’s less draining, you can focus better. At the same time, there’s still an appetite for magazine-feature style stuff, long form, on the internet. Most places that publish that stuff will tell you that it’s consistently their most-read material. And tied to that, the kind of cultural criticism that usually finds a home in a magazine’s back-of-book, again is important, because substantive cultural critique is underserved on the internet. There’s a good case to be made for keeping that in a print product.

But the thing I was struggling with was why. What is the case to be made for bundling together a bunch of short pieces that are unrelated when there’s so much of that stuff online and the internet is way better at doing that type of thing than print is—it’s way better at turning it around, at getting quick hits out. When I sent those tweets, I had an interesting conversation with some people who disagreed, who were making the argument that it’s part of the feel and process of reading a magazine, it’s part of easing the reader in gently. Which I think is totally true as far as it goes, but at the same time the two examples I used of print front-of-books that I think still work and are still important are the New Yorker’s Talk of the Town and Harper’s Readings. In both of those cases it’s because they are iconic sections with their own editorial voices, their own personalities, and most front-of-books just don’t have that. I think there’s a real difference between reading Talk of the Town and reading the front-of-book of Time, which essentially feels like you’re reading the internet a week late. To some extent that is a question of numbers and money, but I think it’s more a question of form. Print will survive a lot longer than people were predicting at the outset of all this, but if that’s true, it does still need to figure out ways to evolve to its strengths.

AB: I’ve been thinking through the arguments against front-of-book, and one thing that came up for me was that timeliness issue—we’re just able to turn stuff around so much faster on the web. But then I was wondering about how we’ve always run columns in newspapers, and the arts section in a newspaper has always had a little bit of crossover with something you might find in a magazine, and so I’m wondering why web has rendered the front-of-book somewhat obsolete when newspapers didn’t.

DN: That’s a good question. I guess I feel like it might be a question of style. Magazine writing, even in the front-of-book, was meant to be different from newspaper arts coverage, but the flexibility of online writing has meant that that division has come down. The form has opened up so much that you can read stuff online that might read a lot like a short magazine piece, in that it’s a lot more personal or a lot looser than something in a newspaper.

AB: In a different direction, a lot of magazines treat the front-of-book like a proving ground for writers they haven’t worked with before. Before someone will okay a feature pitch, they’ll probably try someone out in the front-of-book with a shorter feature. If we were to do away with that shorter feature section of the magazine, what could be substituted in for establishing that relationship with a writer?

DN: I really don’t know. Not much. I feel like the broader takeaway is if there are still reasons to keep this section in magazines, that’s fine, but maybe it needs to be re-thought and everybody needs to work harder to make those sections unique and standalone. Maybe the answer is that every magazine just needs to figure out their Talk of the Town, their Intellectual Situation, their Readings.

AB: I was going to ask you if you had any particular magazines in mind when you were tweeting about the crisis, but you mentioned Time already, and it seems like you think it’s more of a general problem.

DN: Other than that handful I mentioned, I think it’s true of most magazines, which is not to say that good writing doesn’t appear in the front-of-book or that they’re totally useless.

AB: I’m not convinced about Talk of the Town actually. I get it with Harper’s for sure—I love their front-of-book. Harper’s might be the only magazine where I sometimes look forward to their front-of-book more than their feature well. What do you like about the New Yorker’s Talk of the Town?

DN: I like that it has a personality unto itself. People kind of criticize the New Yorker for having a heavy editorial voice but I think that’s part of what gives it the personality—all of the little tics that typify a Talk of the Town piece, like the lack of first-person, the reporter referring to themselves in the third-person as an observer, the deferred resolution at the end of every piece. Nothing is ever pat or neatly tied up, you just feel like you’ve been dropped into something and then pulled out. The way every piece is set up not just as an interview or a profile but as a situation. So even if it’s something as generic as a celebrity profile, they’re always doing something, and it’s not just meeting for lunch—you put them in an interesting circumstance and observe what happens. Certainly you can criticize it for being arch or twee or self-involved, but I think it’s so obvious that Talk of the Town is iconic because it is just a form in itself.

AB: Last question: if you were going to found your own magazine tomorrow, how would you handle your front-of-book?

DN: I have no idea, honestly. I think it would need to be re-imagined in some interesting way, but I don’t know what that would be. Neither of these examples count, because neither of them are monthly general interest magazines in the classic sense, but the Believer and N+1 are the most interesting examples. The Believer in that it doesn’t have a front-of-book. Typically the first thing is the longest and best essay or piece, with shorter stuff sprinkled throughout, but not organized in the way that a traditional magazine is. For N+1, the front of the book is always the Intellectual Situation, which is an unsigned editorial, but it has a really unique voice as well. I would say N+1 is the most interesting example of a newer magazine thinking critically about what to do in that space and pioneering its own form in a way that very few magazines other than the New Yorker and Harper’s have done.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Andrea Bennett is the Associate Editor of Maisonneuve.