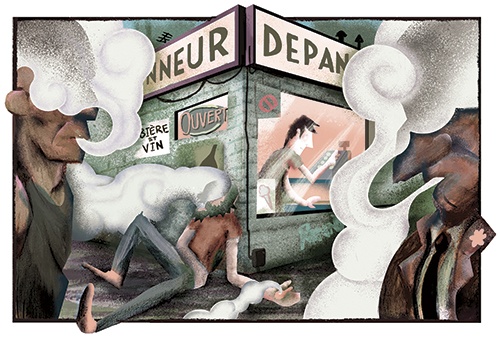

Illustration by Tyler Crich.

Illustration by Tyler Crich.

Will That Be All?

Alex Manley spent years working in a Montreal dépanneur that had something for everyone: cigarettes, newspapers and, beneath the counter, little baggies of mysterious white powder.

I WAS WORKING AT the dépanneur on a Saturday morning in 2011 when I opened the cupboard under our key-cutting machine and saw something I’d never seen before. There, beside our fax machine, was a wooden box with a glass-windowed lid. In it were a dozen little Ziploc baggies filled with white powder.

I waited until the handful of customers in the store had left before kneeling down to take a closer look. The packets had short fragments of text written on them in black marker, things like “Best Brick.” I texted a friend of mine who was a dealer. What’s the street value of cocaine? Pulling out one of the digital scales that we kept in the dusty window display, I weighed a baggie and did some multiplication.

I was twenty-two, my hourly pay within a hair’s breadth of minimum wage. And someone had left $10,000 worth of cocaine just sitting around for me to find during my morning shift.

THE CORNER STORE was in Shaughnessy Village, a little west of Montreal’s downtown core. It had been around for more than a decade when I was hired in May 2010. Ostensibly, it was a magazine and newspaper shop; rows and rows of titles from around the world. Harper’s, the National Enquirer, Der Spiegel. We carried everything. And if a customer couldn’t find what they were looking for, we would order it.

Since magazines have such small profit margins, though, we also carried other items: soft drinks, chocolate bars, chips. We had shelves with high-end pet food and dusty greeting cards. We sold cigarettes and cigars. Our front window displayed pepper spray, knives and extendable steel batons. We carried fireworks. We had cupboards filled with stacks of international calling cards, pouches of salvia and unopened packets of scratch lottery tickets. And we sold a lot of crack pipes.

I’m not sure when exactly the co-owners entered the crack market, but I soon understood why they decided to stick with it. On a newspaper, the store would make pocket change; a crack pipe would net an easy five bucks. The people buying called them stems or glass or tubes, or sometimes nothing at all—saying instead, “you know what I want.” Either way, I’d reach into the cupboard below the cash register and close my hand around the little glass tube, maybe four inches long, smooth and translucent and cool to the touch.

In addition to selling stems, we also manufactured pipe filters—or screens— by purchasing a few bucks’ worth of steel wool at a nearby Dollarama and cutting it into quarter-sized chunks. We sold them for fifty cents apiece. (I later heard the Dollarama stopped carrying steel wool. Rumour was it kept disappearing off the shelves.)

We also made pushes—skinny lengths of wood the width of an iPhone cable and a little longer than a crack pipe—which are used to tamp the steel wool down the stem. That process involved cutting cheap wooden shish kebab sticks in two. We sold each half for another fifty cents. The money added up.

Because of the diversity of what we carried, we had a pretty wide customer base. Or, more accurately, we had several different customer bases. There were the people who lived in the neighbourhood—old regulars who stopped by daily for smokes, newspapers and lottery tickets, or just to shoot the breeze. There were students from the Concordia ghetto who needed fresh-cut keys for their new apartments, and tourists who would wander in off the street to buy a bottle of Coke and ask for directions or advice on scoring weed. There were also the addicts.

The store was a microcosm of its home borough; half of the locals earned under $20,000 a year, according to the 2011 census. And when a neighbourhood is poor, it manifests itself in different ways. Sometimes it’s dramatic, like witnessing a theft or back-alley sex work; other times it’s mundane, like not being able to buy steel wool at the local dollar store.

I MET ROBBIE during my first week on the job. Robbie looked like he was in his early twenties, though his beard and worndown clothes made him seem older. The pleading look in his eyes, however, always reminded me of a child.

From my side of the counter, Robbie’s life appeared to have developed into one big funnel. Strangers gave him coins, which he traded me for bills. He would then use the store’s phone to call his dealer and arrange a meet. He traded the bills for crack. He smoked the crack. Then he started over.

Compared to other substances, crack cocaine is a powerful, extremely addictive high—and a short one. When you’re addicted, you need to get high over and over and over again. It’s cheap compared to the cocaine it’s made from, but if you are buying ten to twenty times a week, it requires a pretty good hustle.

The day I met Robbie, I felt a twinge of guilt as he was leaving the store. I wanted to help him. I asked if he wanted the empty Orange Crush can I had behind the counter. He asked how many, and when I said just the one, he turned it down. I felt like I’d put my foot in my mouth. But as I came to realize over the next few months, the five cents wasn’t worth the five minutes it would take him to return the can.

Robbie made his money by begging aggressively and efficiently, wandering around a section of downtown Montreal and greeting strangers with a repeated chorus of “Ma’am, ma’am!” and “Bro, bro!” It didn’t work on everyone, but it generated a steady, reliable source of change. Robbie was good at what he did.

MOST OF THE CUSTOMERS buying crack paraphernalia wanted to get in and out as fast as possible. They didn’t want to be seen; they didn’t want the other customers to know what they were there for. These buyers would hang back and wait until the store was empty, graciously letting a woman with a copy of Chatelaine go ahead of them in line so they wouldn’t have to buy a pipe with a pair of eyes on their back.

These customers became easy to spot once I knew what to look for. Some wore button-up shirts, pulled crisp bills out of wallets to pay for their pipes and seemed untouched by the drug—pre-Rob Ford, the idea of the suit-wearing crack smoker seemed absurd to me. But the majority of our buyers looked more like what I’d expected. They wore saggy, dirty clothes. They were unkempt, with messy, unwashed hair. Some were my age or younger. Others—the roughest looking—had made it into their thirties and forties. They were men and women, white and black and brown.

Every now and then, one of the newspaper-buying regulars would come in and wax philosophical, inevitably leading to a lament about how the neighbourhood had gone downhill in the last couple of years. Homeless First Nations people seemed to loom large in their minds. I would wince, listening to their casual racism. But I also knew the job had curdled some prejudice into my own thoughts. When someone buying a pack of cigarettes or a lighter or a magazine was a quarter short, I would let it slide like we were old pals. “Don’t worry about it.” I’d wave them off, collecting their change. If anyone was ever short trying to buy a stem or a screen, though, my face would harden. “You know the price,” I’d say. “Come back when you’ve got the money.”

THROUGHOUT MY TWO AND A HALF YEARS working at the store, Robbie was never far away. He would pop in, sometimes three, four times in a shift, asking for the phone, asking for free matches. He would exchange coins for bills or buy a pipe. When he wasn’t in the store, I’d spot him standing around the intersection outside, chasing down potential donors.

I watched people buy him bottles of Coke, which he seemed to ingest in place of solid food. Strangers also gifted him candy and clothes, and one time a man even dropped off a pair of winter boots for him at the store, saying that Robbie had told him that we’d hold onto them. When Robbie stopped by later to pick the boots up, I knew the fact that the bill was still in the bag didn’t mean they were going to be exchanged for a different size.

Everyone in the neighbourhood had a story about Robbie. People would say that he had been a strong student in high school but had spiralled out of control shortly after. One person told me that Robbie’s older brother was a rich and famous DJ, and that Robbie was considered the family embarrassment.

I was stern with Robbie. Occasionally, if I was having a bad shift and he came in and did something to annoy me, I could be cruel. But I could never stay mad at him. I wanted Robbie to be happy, to get his act together. It was painful to watch him live this life. At the same time, I struggled with selling him, and others like him, the tools they needed to slowly annihilate themselves. Punching keys on a cash register, taking bills and coins, I saw them slip through their own lives, already ghosts.

It broke my heart when Robbie was nice to me. Hanging around the counter, he could be so friendly. “I love you, bro,” he’d say. “You know that, right? I love you.” Maybe he really did love me. Or maybe he was just working me, trying to stay in my good graces so he could keep swapping change for bills, keep using our phone for free. I never could tell.

MY PARENTS DIDN’T UNDERSTAND why I stayed at the store so long. But there were upsides. It was a rare service job where I could to spend my shifts in the company of the written word, flipping through copies of the New Yorker and the Atlantic. It felt good knowing the prices of things by heart. I remembered which brands of cigarettes the regulars smoked, how they liked to gamble. Hearing their stories transmuted me from low-wage worker to something of a confidant. And, when my bosses left the premises, the dépanneur became my kingdom.

EARLY ONE SATURDAY MORNING, about six months before I eventually quit, a young man came into the store and asked me for the “fake coke.”

The Ziploc baggies of white powder were still stashed in the cupboard, under the key cutter. I had never asked my co-workers about it. No one ever brought it up. I didn’t know the price. I called my bosses. No answer. I considered the legality of selling fake cocaine while the fake dealer berated me. “I’ve got these tourists ready to buy, man. I need this. Fucking sell it to me!” Eventually I told him I couldn’t because I didn’t know how much it cost. He left, furious.

I suppose I was naive to assume that my bosses would leave $10,000 worth of cocaine lying around where a minimum-wage employee could find it. Like many things I had seen at the store, there was a large gap between what I thought I knew and what I would never understand.