Shoot it Harder, Lads!

At a soccer tournament in Melbourne, a recovering drug addict and ex-soldier taught Dave Bidini that when you love the beautiful game, talent is optional.

TEAM CANADA’S FIRST DAY of competition in the 2008 Homeless World Cup began atop a hill overlooking Birrarung Marr, Melbourne’s major park. Australian organizers had assembled an inflatable red practice pitch that looked like a child’s jumping castle. The players—homeless, refugees and street paper vendors—leapt over its fat borders to find a mesh bag of soccer balls emptied onto the pebbled ground.

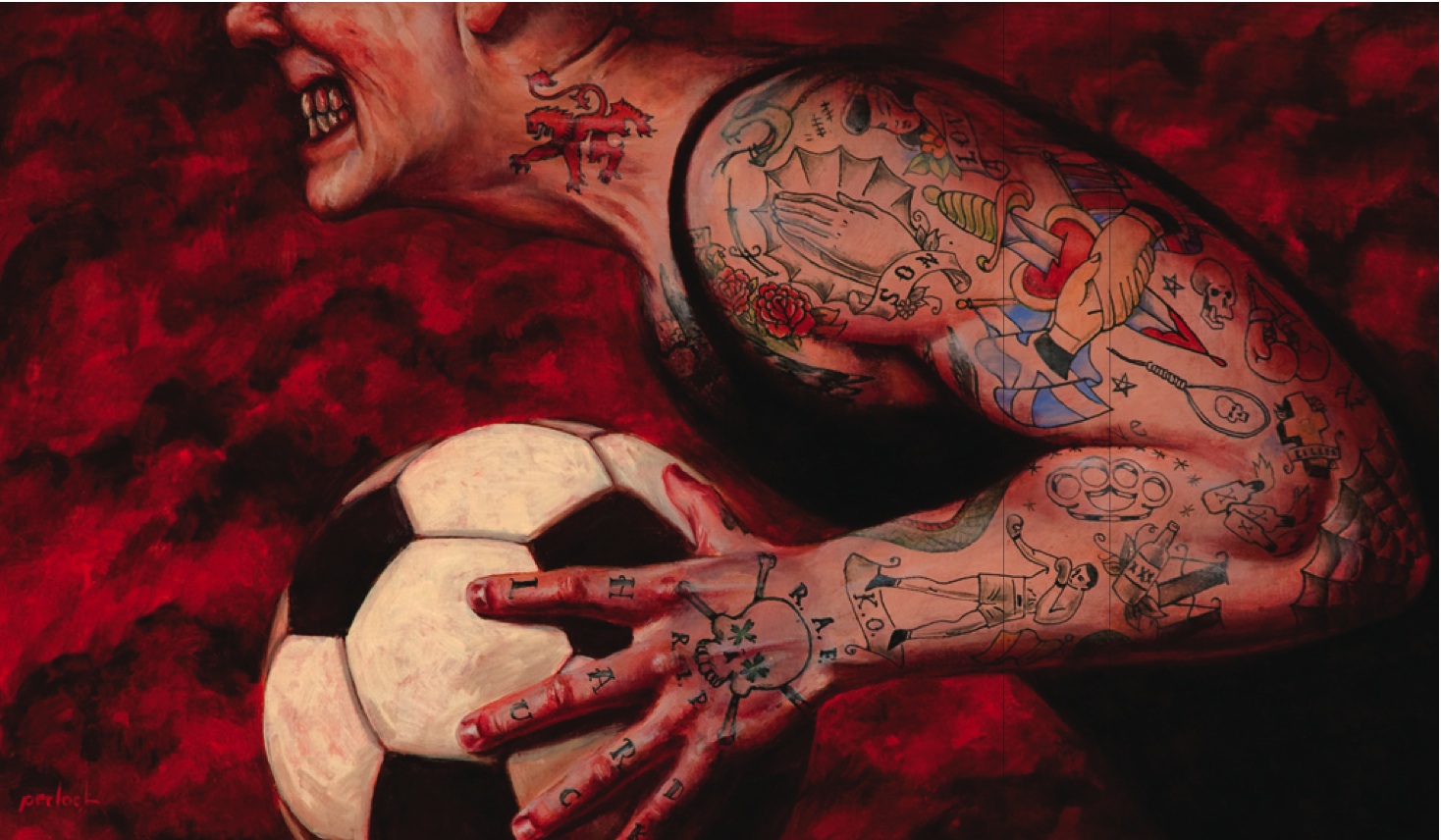

Illustration by John Perlock.

Paul Gregory, director of Street Soccer Canada, and Cristian Burcea, Team Canada’s coach, organized a series of passing and shooting drills—a test of ability after twenty hours of travel and two days in St. Kilda. Balls sprayed around the court as if bursting from a bingo cage. The transcontinental journey clearly hadn’t robbed the Canadians of their skills, and, with the nets empty, nothing stood in the way of their kicks.

This changed, however, once Paul appeared with the team’s substitute goaltender, a fellow named David, from Port of Glasgow, Scotland. He was dressed in a black kilt and slugged up the hill as if steeling his body against an unseen predator. If you didn’t look directly at his hands—which were gnawed and crudely tattooed at the knuckles—you might have thought they were balled into fists, given his tightened haunch and slow, suspicious pace. He had barbed-wire eyes and a small bulldog’s nose, and his rough, time-scribbled face narrated a journey of endless hardship. He squinted at the sun as if trying to pinch the brightness of the horizon into dust, and his teeth forever gritted a burning cigarette, which left a trail of blue smoke behind him as he walked toward his new team-mates.

“This is David, our goalkeeper,” said Cristian, with appropriate formality.

David butted out his smoke under the heel of a boot.

“Caul me Dove,” he said, in a deep molasses of brogue. “They been caulin’ me Dove evah since I was sayven.”

Dove’s legs were also tattooed. So were his arms and his chest. The ink looked like it had been applied with a razor or penknife, born out of a cold cement cell, a deckhand’s quarters, or the back room of a boarded-up storefront. Even though Team Canada’s players had all seen their share of shit and misery, the lingering effects of their hardships were mostly mental. But Dove’s caterpillar scars and the deep grooves that patterned his face seemed physically imprinted with the suffering of his former life.

Dove arrived in Melbourne having recovered from a litany of abuses. He’d grown up poor in a rough city corridor, where his father had taught him how to box. He’d tried getting out by enlisting in the Scottish ranks of the British Army, but it provided no escape from the streets. He was shipped to Belfast, where officers demanded he patrol Fall’s Road in the heart of the Catholic powderkeg. He witnessed endless violence and bombings: streets on fire, burnt buses and bodies flung across a blood-strewn roundabout. As a Scotsman living under British reign, Dove sympathized with the restive Northern Irish. They hated and mistrusted him. The conflict tore at him, ate him up. If the dangers of home had produced only occasional violence, in Belfast it was unrelenting. The comfort and security of a regimental life yielded only chaos and more horror.

One evening, Dove got drunk—soldier drunk—with his fellow troops. Being an accomplished boxer meant that others almost always challenged him. You’re not so fooking tough. Look at you, ya ugly bastard. That gob of yours has taken a fair bit of pounding, eh? With a heart twisted by war and a mind savaged by authoritarian abuse, Dove rose to nearly everyone’s bait. Some paid the price, some didn’t. And one man paid a lot worse than others.

The victim was a young Royal Air Force pilot. He was twenty-two, give or take a year. The pilot was drunk, brave and foolish. Perhaps he was poor, perhaps not. A pilot. Flight academy. Straight chin, fine hands. British forces. Imperialist coonts. “The poor, poor boy,” repeated Dove as he told the story. “It was tarrible, what happened. The poor boy lost his life.”

The army discharged Dove. There was no trial, no jail time. He was sent home, back to Port of Glasgow. The only people who understood him were those who’d also killed. “I was surrounded by death. Death up here, death down there,” said Dove, passing his ravaged hands over his face, chest and stomach. “The only thing left for me to do was join the trade,” he said, referring to Scotland’s raging heroin industry. “I got good at it. Made tons of money. Lived large, you know? Like never before, really. ‘Course I got addicted and that brought the whole friggin’ house down.”

Four times, Dove tried to kill himself. “I tried doing it every which way,” he said, “but I wasn’t even very good at that. This only made it worse. Then, one day, I was hanging a noose around the ceiling pipe in my room. I was ready. It was time. But just as I was about to go, my son walked in. He was fifteen years old. And that’s when I said, ‘No. This is it. This is the end, right here.’”

In recovery, Dove travelled the world, telling his story at Alcoholics Anonymous conventions and, then, joined the Scottish homeless soccer team. Stepping into the goal for Canada, he spat into his gloves and slapped away a few volleys before roaring at his new teammates, “Shoot it harder, lads! C’mon. Shoot it harder!”

AFTER PRACTICE, the team marched down the hill toward the river pitches. One minute, the sun burned hot; the next, a flight of clouds arrived to soften the heat. The courts backed on to one another and were separated by a tented area with little rooms. It looked like a makeshift triage unit. (There was one of those, too, rooted alongside the catering tent on the rooftop of a nearby parking garage.) The scene backstage was a collision of nations: teams who’d just played, were about to play, and were arriving to play next. This global sporting carnival played out to the sounds of an announcer leaning on his elbows and shouting into a microphone, the music of Oasis, AC/DC and Queen—or at least a chorus from one song, then a verse from the other—blaring from the court’s speakers.

The soccer courts were made of black rubber, which absorbed the heat and tended to catch the shoe. The ball itself was almost sticky against the field, more so on days when the sun was at its boldest. The nets were recessed into the field’s framing, and, at times, the goaltenders looked like the guardians of a very small garage. The dimensions of the field were sixteen metres by twenty-two metres: tiny parks that preserved the fast pace of the game and ensured that the physically untuned homeless athlete would not be required to run miles for the ball, which, in the four-on-four street soccer game, ponged off waist-high boards and occasionally jumped like an unwanted house pest in the tight corners of the field.

Over the years, Homeless Soccer had gone through a handful of rule changes, one of which was the three-on-two rule. Like a lot of modern sporting inventions—baseball’s designated hitter, hockey’s shoot-out, basketball’s three-pointer—the three-on-two rule was employed to ramp up scoring. It required that one player per team remain at all times in the offense zone, never crossing the centre line. This ensured two things: first, teams could not “trap” other teams, playing three-men back at all times, and second, there were always three players outnumbering two in the offensive zone. It also meant that, in blowout games, the losing team’s lone offensive player had little to do, and whenever there was a disparity in talent—which there was whenever a sub-par team played Ghana, Afghanistan, Russia or Ireland—the scores were often inflated.

Canada was eventually called to the court opposite the Dutch. The Canadians were supplemented by an Australian reserve, a six-foot-three defender named Pommie, who was cast head-to-toe in tensor bandages to protect injuries he’d suffered in training sessions leading up to the tournament.

After warm-ups, both sides moved to the centre line for the national anthems. A high school orchestra’s wonky recording of “O Canada” came over the speakers as the team stood in front of a few hundred fans gathered in the bleachers. The music evoked the dusty winter warmth of a small classroom, a music instructor in a plaid sweater and pleated corduroys furiously waving a baton. The Canadians sang along, chins tilted to the skies. At the far end of the line, Dove did, too, if a few beats behind to shadow words he was hearing for the first time. When the song ended, the referee—a tall, cadaverous gentleman dressed in black—called players into position, then blew his whistle as the ball was booted into play.

The game started with a flurry of nervous energy; chests heaving, arms and ankles swinging. The wild orange sweaters of the Dutchmen swirled against the black rubber of the pitch and, for the first few minutes, the Canadians looked like keystone cops chasing after Halloween truants. The Dutch seemed fitter, better and more organized, so it was no surprise when they opened the scoring with four quick goals, blasting Dove with shots from every corner of the field. Their team had a distinct advantage over the Canadians, possessing twice the number of players on their roster, which they’d assembled after a series of national playdowns featuring a dozen homeless soccer teams. The Dutch had no tensor-wrapped Pommies; only swift-footed Edgar Davids dopplegangers who bumped the score to five-zero before Canada made its first substitution: Juventus for Krystal.

Despite the change, the Dutch kept shooting. This might have disheartened lesser competitors, but Dove faced each shot as if he welcomed the ball’s rough hide, punching away volleys like a child to his birthday balloons. Whenever he rolled across the crease to capture a ball, he came up with his teeth to the grill, devouring every delicious second of action. It was the kind of reaction one might have expected from a person who’d conquered the terrible ravages of his life. While falling behind seven-zero probably wasn’t the greatest start to his tournament, considering all that had happened in the player’s life, it also sort of was. Even in lopsided drubbings like these, at least he was playing.

Juventus, a young Moroccan-Canadian, ran around the field like a dog set loose from its chain, his pomp of hair pitching from side to side. Almost instantly, he flung himself into the fray in an attempt to take the ball from one of the tall Dutch forwards. But in doing so, he ended up planting his knee on the unforgiving rubber and twisting it. Juve felt a shudder of pain in his kneecap and a sharp popping sound was audible from the sidelines. He slumped to the turf and rubbed his leg. Juve’s implacable repose soon faded into grief and disappointment as he drew himself up from the grounds and limped in slow, agonizing steps to the sidelines. Cristian was hopeful that his injury would be the kind that only needed to loosen before it healed, but when Juve stopped walking, leaned against the sidelines and groaned, the coaches and players knew to expect the worst.

The bad news didn’t end there. Early in the second half, Dove lunged after a rolling ball, trapped it heroically, then lay prone in the goalmouth holding his thigh. His hard expression remained, but, as he clambered to his feet, his body was tilted to one side as if favouring his right leg. Cristian yelled at him, asking if he was okay, but Dove refused to ask for time. The shots kept coming, almost every one of them a goal. Cristian yelled at him again, but Dove simply looked away and held up the flat of his gloves, continuing to play.

At game’s end, having lost nine-two, the bedraggled Canadians turned to comfort their goalie. “Way to go out there, Doug,” said one player, but no one had the energy to correct him. Dove had stretched a groin, ending his tournament in red and white. He stayed with his team—Scotland—and helped coach from the bench, but, in the end, never played another game.

Related on maisonneuve.org:

—The Great Comeback

—Sex and the World Cup

—The Old One-Two

Subscribe to Maisonneuve — Follow Maisy on Twitter — Like Maisy on Facebook