Illustration by Jenna Andersen

Illustration by Jenna Andersen

Rinse and Repeat

Washing meat is tradition in Black homes, writes Jody Anderson. The practice shouldn’t need defending.

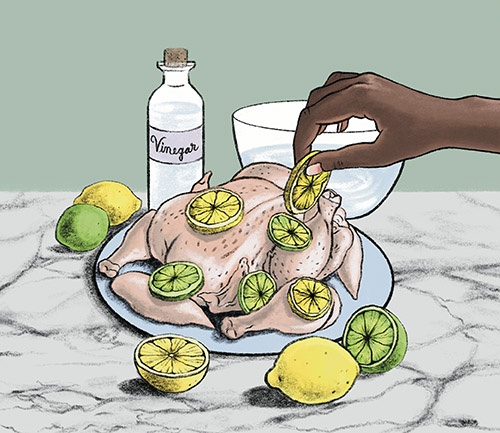

The first step of preparing a meal for loved ones in most Black households is washing the meat in a mix of water and lemon, lime or vinegar. I like to watch my mom rub half of a citrus against a whole chicken while she tightly grips the leg, her motions precise and natural. There’s something purifying about the process. The act of cleaning meat summons a rustic connection to food, evoking a time when meat came from the farm and we felt its feathers and skin between our fingers as we prepared it to be seasoned and cooked. For many people who still buy their meat from markets and directly from farms, that’s still the case.

This practice is hard for white food and health scientists to accept. To them, washing meat remains an unnecessary step because when chicken comes from factories, it’s cleared of any inedible entities: skin, bone, gunk. Yet we persist—not because we are simply repeating nonsensical behaviour, but because the practice has been passed down for decades within Black homes and is, in a way, tradition. Washing meat is a presumed part of cooking in our families and family lines. It doesn’t need to be spelled out in cookbooks, though sometimes it is.

My dad says he didn’t always clean meat as intensely in Jamaica as he does here. “Back home, you buy fresh chicken and he just kills it and carries it to you. You don’t need to do a whole lot of washing. Squeeze a little lime on it, yes, and get it ready.” Holding onto culinary practices that have been taught to us by our parents, or taught to them by ancestors we’ll never meet, forges a connection that transcends borders, bloodlines and the afterlife.

But another aspect of tradition we hold dear is relying on our community’s shared wisdom and collective agreement to not trust white interjections. For us, cleaning meat is a matter of trust. We don’t know what’s going on behind the scenes in people’s homes or factories, and we’ve been led to believe, through past interventions that have erased or diminished our cultural practices, that we can rely on our instincts more than condescending scientists.

I didn’t consider what was happening in other people’s kitchens until 2018, when Marci Ien asked the audience of The Social, “Does anybody wash their meat?” During that episode, the hosts of the daytime talk show were discussing “rip and tip bags” that allowed people to transfer meat from package to pan without ever touching it. Ien, the only Black host, reacted exactly how I’d expect many Black women to react in a professional space: instead of saying “Bitch, what?” her face did the work.

She then asked the question that launched an online debate. The comments sections on Facebook and Twitter lit up with Black people’s collective distrust of Western meat handling and the steps they follow when cleaning meat themselves. To some, cleaning meat just meant rinsing off the slime, blood and debris collected during its transition from factory to store. For others, the process included removing the innards and unwanted fat. Commenters laughed at detractors’ remarks that they were spreading germs in their sinks and asked, “You guys don’t clean your sinks?” They giggled over the irony of being judged by people who “barely have a relationship with salt and pepper” and “don’t wash their asses.”

There’s another irony to white people’s shock over the practice. There was a time when Julia Child and James Beard told their predominantly white audiences to wash their meat. In the 1968 edition of Mastering the Art of French Cooking (Volume 1), the authors write, “If you wash the chicken … do so rapidly under cold, running water.” In Beard’s 1972 edition of American Cookery, he instructs home cooks following the recipe for his Stuffed Poached Chicken to “wash the chicken or fowl and rub the interior with lemon juice.” It’s unclear when meat washing started to be discouraged in North American homes, but the practice seems to have fallen out of favour in white kitchens over the following decades.

By 2019, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) denounced meat washing, claiming it was a health risk. White food and health experts explained that the practice risks spreading bacteria and exposing people to foodborne diseases. Yet according to a study completed the same year for Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS) and by food and safety experts at North Carolina State University, bacteria spreads whether people wash their chicken or not. The main cause of the spread is likely from contaminated hands, or microbes from either the chicken or packaging sitting in the sink. The researchers concluded that the priority should be educating the public about proper hand and sink sanitization rather than constantly telling people not to wash their meat.

And yet, after the CDC denouement, we were the majority in the comments again, having to explain how thoroughly we clean our kitchens, that our goal is to get rid of unwanted matter and that we simply don’t have faith in the cleanliness of the meat from the stores. Ultimately, what Black and other non-white home cooks have been practicing for years continues to be dismissed because white people don’t get it. It has to be overexplained, rationalized, repeated and proven through statistics, like I’m doing now, to be respected. For the CDC and anti-meat cleaning patronizers, our values mean nothing if they’re not understood or approved by white sensibilities.

As the Black diaspora carried on washing meat, it became clear that anti-cleaning meat discourse was scolding us in order to affirm white standards of hygiene and cleanliness. People from cultures that wash their meat for religious purposes, such as the Jewish community when cultivating kosher meat, didn’t receive the same critical attention from food safety researchers as those who do it for cultural purposes, like Black, Asian and Latine communities.

This is far from the first time white experts’ interventions have attempted to distort our relationship with food and our bodies in order to establish superiority. In the eighteenth century, when colonizing Europeans noticed that Africans were fat like them, they determined that fatness was immoral. According to Sabrina Strings, a professor of sociology at University of California, Irvine and author of Fearing the Black Body: The Racial Origins of Fat Phobia, Europeans rationalized their need to be slimmer by associating Blackness with savagery.

In an interview with NPR, Strings explains the line of thinking held by colonizers: “Africans are sensuous. They love sex, and they love food. And for this reason, they tend to be too fat. Europeans, we have rational self-control. This is what makes us the premier race of the world. So in terms of body size, we should be slender, and we should watch what we eat.” This framework established the Western parameters for what was “healthy”—and established that Black people were not.

When health is determined by white experts, it creates scientifically racist structures such as the Body Mass Index that denigrate what comes naturally to us, like our bodies and what we eat. It also creates racist mainstream narratives about food. In 2017, Toronto Star health reporter Megan Ogilvie mispronounced chicken roti as “roadie” when she profiled the dish and compared it to “eating twenty-eight chicken McNuggets.” The classic Caribbean meal was dissected by a dietician who suggested “health-conscious diners” should only eat half of it to reduce their calorie intake.

White people have historically challenged practices from other cultures that threaten their interests in order to establish a hierarchy. In the Atlantic, William R. Black, a historian of American culture, writes about white American farmers who were bothered by formerly enslaved Black people profiting from selling watermelons. So they used the fruit’s messy-to-eat and easy-to-grow properties to transform it into a symbol of uncleanliness, one that would present Black people as dirty and lazy.

White people also tried to establish dominance over Indigenous communities in the Prairie West when colonizers tried to suppress their food practices. Tabitha Robin, a Cree and Métis researcher and educator, explains how settlers intervened with Indigenous culinary culture. They introduced a permit system to restrict farming on reserve to a subsistence level. They also implemented a ban on machinery and subdivided reserves, limiting the lands available for farming. These regulations intended to shut down on-reserve agricultural production in an effort to make sure Indigenous people didn’t pose competition to non-Indigenous farmers.

This long history of hatred and scientific racism explains why white people’s attempted interjections into Black food and health aren’t trusted. Non-white communities have suffered greatly when scientists have intervened and fractured our relationships with food. Anti-meat cleaning discourse, shared through studies, articles, tweets and videos, tends to have a condescending tone. Warnings about washing meat originate from a place of superiority disguised as care. Our traditional practice of washing meat is belittled by science, not out of concern, but to affirm dominance. Even the word “habit,” used in a FSIS report which compared cleaning meat to the potentially fatal practice of driving without a seatbelt, reads like those anthropological studies of communities white scientists and explorers viewed as “uncivilized.”

Ronke Edoho, a nutrition specialist and food blogger, grew up in Nigeria where she says the way she handled meat was completely different from how she’s seen it handled in Canada. In Nigeria, she’d buy her meat from an open market, and there would be more visible parts that needed removing. But for Edoho, what needs removing in Canada is a strange smell that she says the meat picks up in factories. So she keeps washing her meat here; her standards of clean are different from Western society’s.

Edoho says Western science strips distinct values and knowledge from cultural practices. “When it comes to your food, when it comes to tradition, when it comes to culture practices, context is important,” she says. “But when it comes to science, that context is often missed.”

The effects of this condescension stretch beyond our kitchens. Idil Farah, a nutritionist and educator who leads workshops about food, identity, culture and health, says culinary practices are valuable in strengthening a person’s cultural identity. Farah grew up in a Somali home where the kitchen was the hub of the house. While studying food and nutrition at Toronto Metropolitan University, Farah learned there were so many things she wasn’t “supposed to do” and briefly adopted Eurocentric cooking methods. In time, though, going back to her culture felt necessary because when “you try to integrate so much, you lose pieces of yourself.”

She believes washing meat is one cultural practice that anchors people. “It brings you back home to yourself. It brings you back to all the things that are familiar about food,” she says. In her workshops, she combines nutritional counselling with lessons on the value of flavour, an element she thinks is woefully missing from Western perspectives of health. “Food is flavour. Food is comfort. You eat it with your senses, your taste, your eyes. When you think about nourishing yourself, you can’t separate it into vitamins and minerals and what it’s doing for [your] body.”

Many food and health scientists, behaving as authority figures, believe we should restructure our practices to fit their rules. The reality is the studies and anger directed our way have more to do with seeing us comply with their parameters of health, cleanliness and goodness than it does with genuine care for our wellbeing. It’s true, washing meat can spread bacteria. But it will spread whether it’s washed or not. What they seek is to enforce submission by insisting we lack knowledge. And what we seek is for them to stay out of our homes, like we do theirs.

I was raised not to eat food at other people’s houses. My mom always said you don’t know how they cook or what’s in their home. Black people have collectively groaned over seeing cats on people’s kitchen counters, on tables and near their food. I didn’t listen to my mom and ate at a colleague’s place once, only to learn they don’t wash their fruit after bringing it home from the grocery store. It made me cringe.

By washing meat, we know it’s being prepared in a way we feel is safe and protects our loved ones. Our handling of meat from farm to table has been passed down from generation to generation and across the diaspora. So maybe washing meat is a nostalgic way to cleanse it of its Western attachments and make it a true part of our homes. ⁂

Jody Anderson is a Toronto-based culture writer and project manager. She enjoys travelling, getting outside of her comfort zone and being an auntie.