Illustration by Frenchfold

Illustration by Frenchfold

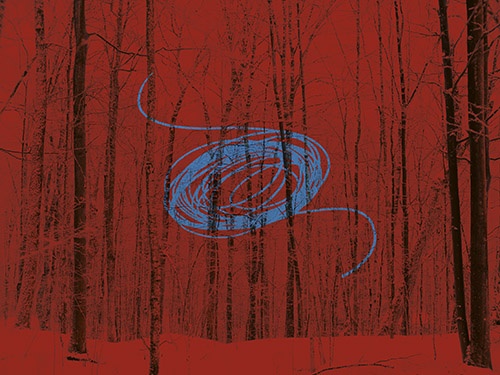

The Secret Wounds of Maple Trees

Translated by Katia Grubisic

“A cut is a wound,” Sylvain had said. “How you do it matters. And prying out the spile is even more important: if you apply too much force you can rip off the bark, and it takes years to heal. The tree dies from the inside and you never see it coming, until next thing you know there’s no more sap. You owe it to the tree to wound it correctly. I know that sounds kind of silly, but that’s really how it is. You don’t have a choice, there’s an element of harm involved in tapping maples. If you do it right, it’ll heal slowly, and then you can choose the best place to drill the next hole and let the old one heal. You understand? It’s cyclical. You make a new hole just far enough away from the old one, and everybody’s happy and the sap keeps flowing. The drill bit you use makes a difference too. You want a clean, even hole, you don’t want it chewed up all over the place with lots of hidden lacerations, you know? Measure your angle twice or even three times if you have to, adjust your bit, take your time. You’re hurting that tree every single time; never forget that. It’s like slaughtering animals on a farm. It’s necessary, but it’s violent. People don’t like to think about the violence behind their barbecue chicken, and I get that, I don’t like violence any more than anybody else. But that’s all your tree wants from you: be careful, because you know it hurts.”

Adam told Marion what Sylvain had taught him. As he spoke, he realized he was having a hard time looking at her, his eyes were everywhere except on her. The blue tubing looped from one tree to another in a low curve. A plane high up in the sky. His own snowshoes on Marion’s feet.

She hadn’t brought snowshoes, although he had asked her to, and he had given her the ones Sylvain had made him buy back in January. Adam had come out on cross-country skis, and hadn’t been able to get even ten feet into the woods. The trees were too close together, the ground was too steep. Sylvain had laughed: typical city boy notions.

Adam’s snowshoes were too big for Marion, and he knelt down in front of her to tighten the straps as much as possible, holding his gloves between his teeth. He stared hard at the pile of snow between his boot and the snowshoe, going on about the secret wounds of maple trees, aware of the metaphorical weight of what he was saying, love welling up everywhere like spring runoff. Probably that was why he couldn’t look at her. How odd it was to forget how to gaze into eyes he knew so well.

In the end, it was better to say nothing at all, and they spent the day tapping trees in silence. They finished up as darkness fell. ⁂

Fanny Britt is a writer and translator living in Montreal. Among others, she has written the novel Les maisons (Hunting Houses) and the graphic novel Jane, the Fox and Me. Her second novel, Faire les sucres, won the Governor General's Award in 2021. As a translator, she has adapted the works of Dennis Kelly, Martin McDonagh, Annabel Soutar and Lisa Moore.

Translated from Faire les sucres (2020), published by Cheval d’août. Reprinted with permission from the publisher. The novel is forthcoming in English from Book*hug, translated by Susan Ouriou.